- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Small-for-gestational age (SGA) refers to an estimated fetal weight (EFW) or abdominal circumference (AC) below the 10th centile on a customised growth chart. Severe SGA refers to an EFW or AC below the 3rd centile.

Around 60% of SGA fetuses are constitutionally small, meaning that fetal growth is appropriate for maternal size and ethnicity.1

Some fetuses with SGA, particularly severe SGA, will have fetal growth restriction (FGR) as well. FGR implies a pathological restriction of the genetic growth potential- this can be placental or non-placental mediated growth restriction. As a result, growth-restricted fetuses may manifest evidence of fetal compromise (e.g. abnormal Doppler studies, reduced amniotic fluid volume).

Aetiology

SGA fetuses are divided into the following categories:

- Constitutionally small

- Fetal growth restriction (FGR): either non-placental mediated growth restriction or placental mediated growth restriction

Constitutionally small

SGA fetuses are constitutionally small, meaning that they have reached their genetic growth potential, in keeping with maternal size and ethnicity.

Fetal growth restriction

Non-placental mediated growth restriction

Fetuses who have not reached their growth potential, for reasons other than those related to the placenta.

Examples include fetuses with chromosomal or structural abnormalities, fetal infection, or inborn errors of metabolism.

Placental mediated growth restriction

Fetuses who have not reached their growth potential, due to problems with the placenta such as abnormal implantation and vasculature.

Examples include pre-eclampsia, autoimmune disease, thrombophilia, renal disease and essential hypertension.

Maternal factors can also affect the transfer of nutrients across the placenta, such as low pre-pregnancy weight, malnutrition or severe anaemia.1

Risk factors

All women should be assessed for SGA risk factors at their booking visit. The presence of risk factors warrants increased pregnancy surveillance.1

Broadly, SGA risk factors can be divided into major (odds ratio >2.0) and minor (odds ratio <2.0).

Major risk factors

Major risk factors for SGA include:

- Previous stillbirth

- Previous SGA fetus

- Cocaine use

- Maternal age >40 years

- Maternal disease: chronic hypertension, renal impairment, diabetes with vascular disease, antiphospholipid syndrome

- Threatened miscarriage

- Low pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A (PAPP-A) – a placental hormone

- Pre-eclampsia

- Cigarette smoking

Minor risk factors

Minor risk factors for SGA include:

- Nulliparity

- In-vitro fertilisation singleton

- Maternal BMI <20 or >25

- Previous pre-eclampsia

Any woman with one major risk factor will be referred for serial growth scans, which are essential to monitor and diagnose SGA.

If a woman has three or more minor risk factors, she should be referred for uterine artery Doppler at 20-24 weeks gestation. Women with abnormal uterine artery Doppler should also be referred for serial growth scans.

Clinical features

History

A thorough obstetric history at the booking visit is vital to identify any of the risk factors listed above.

A constitutionally small SGA fetus is unlikely to present with any maternal symptoms.

Pre-eclampsia is a major risk factor for SGA. Women with pre-eclampsia may be asymptomatic (diagnosed on routine BP/urinalysis) but can present with severe headache, visual disturbances, epigastric pain and sudden onset oedema of the hands, face, and feet.2

Examination

For patients with no risk factors, SGA fetuses are usually detected during routine obstetric assessment.

Typical findings of a suspected SGA fetus, include:

- Symphysis-fundal height below the 10th centile

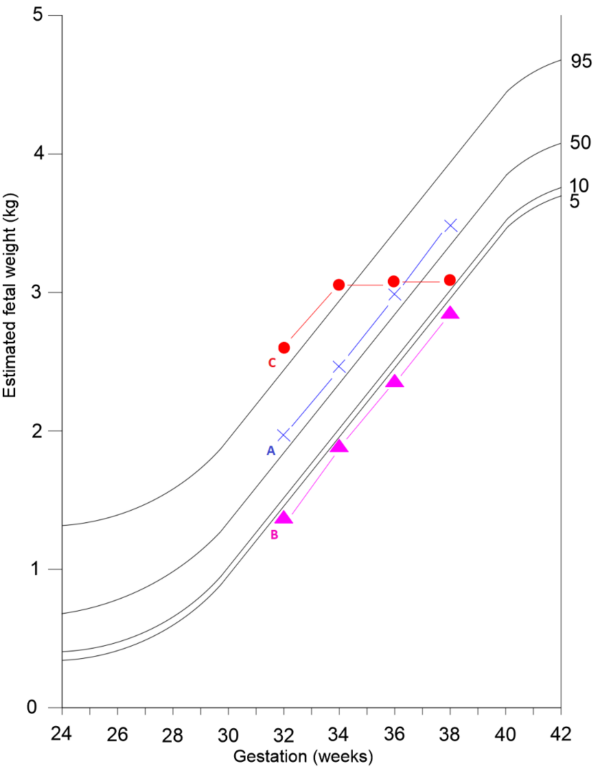

- Low estimated fetal weight – serial measurements suggesting slow or static growth (Figure 1)

Investigations

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations, performed on every pregnant woman, include:

- Blood pressure: to screen for pre-eclampsia

- Urine dipstick: to screen for pre-eclampsia

- Cardiotocography (CTG): if fetal compromise is suspected, CTG can be used to assess fetal heart rate, from which the degree of fetal hypoxia can be inferred

Laboratory investigations

Additional laboratory investigations which may be appropriate for severe SGA, include:

- Serological screening for congenital cytomegalovirus and toxoplasmosis infection

- Karyotyping for fetuses with structural abnormalities; amniocentesis antenatally3

Ultrasound

Serial ultrasound scans

Serial ultrasound scans (USS) are the key investigative tool for diagnosis and surveillance of SGA fetuses, performed from 26-28 weeks gestation. For fetuses at risk of SGA, USS measurement of size and assessment of wellbeing with umbilical artery Doppler is performed every 3-4 weeks until delivery.

Fetal biometric measurements are plotted on a customised growth chart4

Umbilical artery Doppler

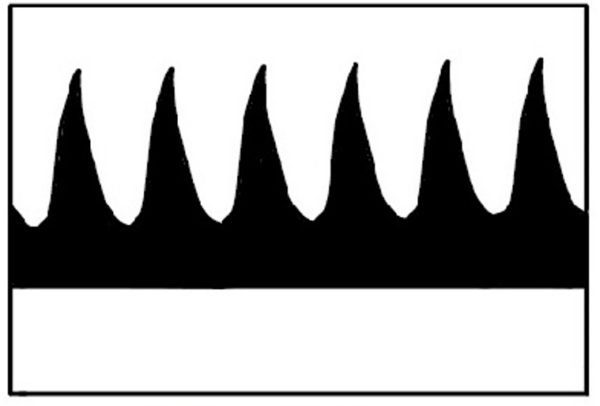

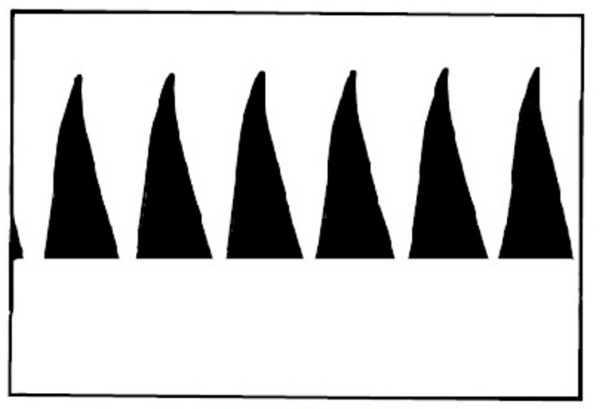

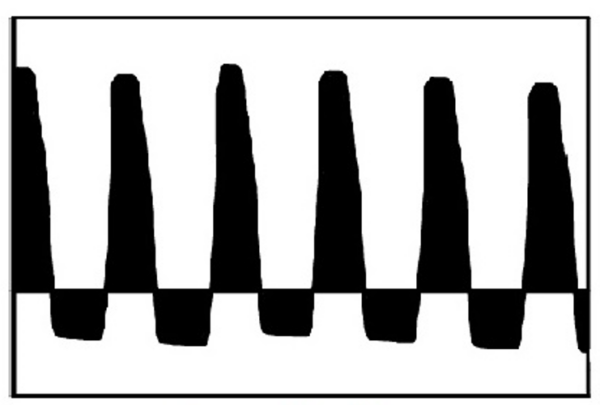

Umbilical artery Doppler is used to assess fetal wellbeing. Table 1 shows examples of normal and abnormal umbilical Doppler waveforms. If there is a normal Doppler it should be repeated in at least 14 days. An abnormal Doppler should be repeated more frequently, and expediting delivery should be considered.

Table 1.Doppler waveforms in a fetus with suspected SGA

Middle cerebral artery Doppler and ductus venosus Doppler can also be used to help time delivery of the SGA fetus.1 If these are abnormal then some degree of harm may have already occurred to the fetus, and delivery should be planned immediately, often by caesarean section as the fetus will not tolerate any potential hypoxia in labour.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of SGA is made from USS assessment of EFW or AC:

- SGA = EFW OR AC is less than the 10th centile on a customised growth chart

- Severe SGA =EFW OR AC less than the 3rd centile on a customised growth chart

Management

Conservative management

Managing modifiable risk factors during pregnancy is essential, including:

- Smoking cessation

- Drug counselling

Medical management

Women with co-morbidities (e.g. hypertension, renal disease) should be medically optimised before and during pregnancy to reduce the risk of SGA.

In women at high risk of pre-eclampsia, antiplatelet agents (e.g. aspirin 150mg daily) should be commenced at 12 weeks gestation until the birth of the baby.

Delivery

Expedited delivery must be considered for an SGA fetus, with evidence of fetal compromise (Table 2). Delivery may be induced either vaginally or by C-section, depending on other features of the pregnancy.

Table 2. Recommended mode of delivery for an SGA fetus.1

|

Gestation |

Umbilical artery Doppler |

Mode of delivery |

|

<37 weeks |

Absent/reversed EDF |

Recommend Caesarean section

|

|

≤37 weeks

|

Abnormal |

Offer induction of labour |

|

At 37 weeks

|

Normal |

Offer induction of labour |

Women with a SGA fetus between 24+0 and 35+6 weeks of gestation, where delivery is being contemplated, should also receive a single course of antenatal corticosteroids.5

Complications

Structurally normal SGA fetuses are at increased risk of perinatal mortality and morbidity, however, the majority of adverse outcomes are concentrated in the FGR group.

Neonatal complications of FGR include:6

- Iatrogenic prematurity

- Antenatal or intrapartum asphyxia

- Operative delivery

- Perinatal death including stillbirth

- Neonatal hypoglycaemia and hypocalcaemia

- Necrotising enterocolitis

After the neonatal period, babies born with FGR are more likely to suffer long-term disability (e.g. cerebral palsy). They are also more likely to suffer from type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease in their adult life.

Key points

- SGA fetuses are those with an EFW or AC less than the 10th centile.

- Risk factors for SGA include previous SGA baby, increasing maternal age and pre-eclampsia.

- There are often no clinical features in a woman with an SGA fetus, particularly where the fetus is constitutionally small.

- USS is used to diagnose SGA and serves as the primary surveillance tool.

- Management consists of smoking cessation and optimisation of maternal disease.

- Where there is evidence of fetal compromise, early delivery of the fetus must be considered.

- FGR fetuses are more likely to suffer from antenatal/intrapartum asphyxia, perinatal death and long-term disability.

References

- Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. The Investigation and Management of the Small-for-Gestational-Age Fetus. Published in 2013. Available from: [LINK]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy. Published in 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. Amniocentesis and Chorionic Villus Sampling. Published in 2010. Available from: [LINK]

- Perinatal institute. Growth Assessment Protocol Care Pathway. Published in 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Published in 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Fetal Growth and Surveillance. Published in 2019. Available from: [LINK]

Reviewer

Miss Karen Moores

Consultant Obstetrician