- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

This guide provides an overview of the recognition and immediate management (including thrombolysis) of stroke using an ABCDE approach.

The ABCDE approach can be used to perform a systematic assessment of a critically unwell patient. It involves working through the following steps:

- Airway

- Breathing

- Circulation

- Disability

- Exposure

Each stage of the ABCDE approach involves clinical assessment, investigations and interventions. Problems are addressed as they are identified and the patient is re-assessed regularly to monitor their response to treatment.

This guide has been created to assist students in preparing for emergency simulation sessions as part of their training, it is not intended to be relied upon for patient care.

Background

Someone in the UK will have a stroke every 5 minutes, with 100,000 people having strokes yearly. Cerebrovascular diseases are the 4th most common cause of death in the UK, with 75% of those deaths being from stroke.1

There are two main causes of stroke:2

- Ischaemic (85%): due to a lack of blood supply to part of the brain

- Haemorrhagic (15%): due to an intracerebral haemorrhage

Clinical features

Symptoms of stroke vary depending on the type of stroke and the area of the brain affected. For more information on history taking, see our guide to stroke and TIA history taking.

Ischaemic stroke

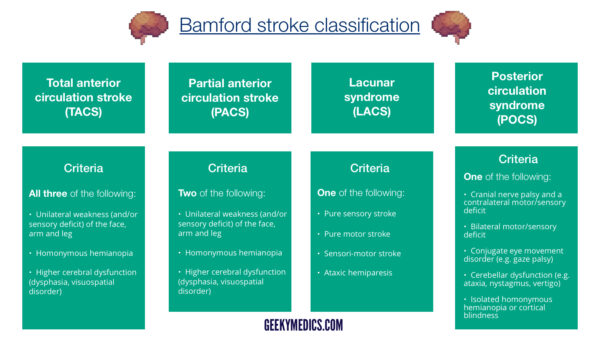

The Bamford stroke classification divides the different types of stroke into TACS, PACS, POCS and LACS, depending on the clinical features.

A TACS (total anterior circulation stroke) is caused by an infarct affecting the areas of the brain supplied by the middle and anterior cerebral arteries, and it causes:

- Unilateral weakness (and/or sensory deficit) of the face, arm and leg

- Homonymous hemianopia (loss of half of the visual field in both eyes)

- Higher cerebral dysfunction (dysphasia, visuospatial disorder)

A PACS (partial anterior circulation stroke) is caused by an infarct that only affects part of the anterior circulation and causes two of the above, or higher cerebral dysfunction alone.

A POCS (posterior circulation syndrome) is caused by an infarct affecting the posterior circulation, which supplies the cerebellum and brainstem, and it causes:

- Cranial nerve palsy with a contralateral motor or sensory deficit, or

- Bilateral motor/sensory deficit, or

- Conjugate eye movement disorder, or

- Symptoms of cerebellar dysfunction such as vertigo, nystagmus or ataxia, or

- Isolated homonymous hemianopia

A LACS (lacunar stroke) is subcortical; therefore, higher cerebral functions (e.g. language) are preserved. Hence, these can be pure motor, sensory, sensorimotor, or cause ataxic hemiparesis alone.3

Haemorrhagic stroke

There are two kinds of haemorrhagic stroke, intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH) and subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH):

- Intracerebral haemorrhages present with stroke symptoms, similar to those of an ischaemic stroke, depending on the area of the brain that has been affected. They can also present with a reduced level of consciousness and headache.

- Subarachnoid haemorrhages classically present with a sudden onset, “thunderclap” occipital headache, usually associated with severe pain. There may also be associated neck pain and a reduced level of consciousness.

BEFAST

The BEFAST acronym is used to help members of the public identify a stroke:

- Balance: sudden loss in balance?

- Eyes: loss of vision or double vision?

- Face: is there a facial droop?

- Arms: can the person lift both arms above their head?

- Speech: is the speech slurred, or are they using inappropriate words?

- Time: time to call an ambulance

This can be useful to keep in mind, as it is helpful for the quick identification of ‘classic’ strokes.

Stroke mimics

There are several conditions which can mimic a stroke. When assessing a suspected stroke patient, it is important to consider these differentials.

Common stroke mimics include:

- Seizures (Todd’s paresis)

- Migraine

- Bell’s palsy

- Vestibular neuritis / BPPV

- Head injuries

- Exacerbation of an old stroke

- Space-occupying lesions (e.g. tumours)

- Demyelinating disorders (e.g. multiple sclerosis)

- Delirium

- Sepsis and central nervous system infections

- Hypoglycaemia and hyperglycaemia

- Intoxication with alcohol or drugs

Tips before you begin

General tips for applying an ABCDE approach in an emergency setting include:

- Treat all problems as you discover them.

- Re-assess regularly and after every intervention to monitor a patient’s response to treatment.

- Make use of the team around you by delegating tasks where appropriate.

- All critically unwell patients should have continuous monitoring equipment attached for accurate observations.

- Clearly communicate how often would you like the patient’s observations relayed to you by other staff members.

- If you require senior input, call for help early using an appropriate SBAR handover structure.

- Review results as they become available (e.g. laboratory investigations).

- Make use of your local guidelines and algorithms in managing specific scenarios (e.g. acute asthma).

- Any medications or fluids will need to be prescribed at the time (in some cases you may be able to delegate this to another member of staff).

- Your assessment and management should be documented clearly in the notes, however, this should not delay initial clinical assessment, investigations and interventions.

Initial steps

Acute scenarios typically begin with a brief handover including the patient’s name, age, background and the reason the review has been requested.

In the context of a stroke, the handover may be from nursing staff (for in-hospital strokes) or ambulance staff (for pre-hospital strokes).

Introduction

Introduce yourself to whoever has requested a review of the patient and listen carefully to their handover.

Interaction

Introduce yourself to the patient including your name and role.

Ask how the patient is feeling as this may provide some useful information about their current symptoms.

Preparation

Make sure the patient’s notes, observation chart and prescription chart are easily accessible.

Ask for another clinical member of staff to assist you if possible.

If the patient is unconscious or unresponsive, start the basic life support (BLS) algorithm as per resuscitation guidelines.

Airway

Clinical assessment

Can the patient talk?

Yes: if the patient can talk, their airway is patent and you can move on to the assessment of breathing.

No:

- Look for signs of airway compromise: these include cyanosis, see-saw breathing, use of accessory muscles, diminished breath sounds and added sounds.

- Open the mouth and inspect: look for anything obstructing the airway such as secretions or a foreign object.

Causes of airway compromise

There is a wide range of possible causes of airway compromise including:

- Inhaled foreign body: symptoms may include sudden onset shortness of breath and stridor.

- Blood in the airway: causes include epistaxis, haematemesis and trauma.

- Vomit/secretions in the airway: causes include alcohol intoxication, head trauma and dysphagia.

- Soft tissue swelling: causes include anaphylaxis and infection (e.g. quinsy, necrotising fasciitis).

- Local mass effect: causes include tumours and lymphadenopathy (e.g. lymphoma).

- Laryngospasm: causes include asthma, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) and intubation.

- Depressed level of consciousness: causes include opioid overdose, head injury and stroke.

Interventions

Regardless of the underlying cause of airway obstruction, seek immediate expert support from an anaesthetist and the emergency medical team (often referred to as the ‘crash team’). In the meantime, you can perform some basic airway manoeuvres to help maintain the airway whilst awaiting senior input.

Head-tilt chin-lift manoeuvre

Open the patient’s airway using a head-tilt chin-lift manoeuvre:

1. Place one hand on the patient’s forehead and the other under the chin.

2. Tilt the forehead back whilst lifting the chin forwards to extend the neck.

3. Inspect the airway for obvious obstruction. If an obstruction is visible within the airway, use a finger sweep or suction to remove it.

A health-tilt chin-lift should not be performed in patients with a potential spinal injury. Strokes can present with collapse, leading to concerns regarding the C-spine, especially in those over 65.

Jaw thrust

If the patient is suspected to have suffered significant trauma with potential spinal involvement, perform a jaw-thrust rather than a head-tilt chin-lift manoeuvre:

1. Identify the angle of the mandible.

2. With your index and other fingers placed behind the angle of the mandible, apply steady upward and forward pressure to lift the mandible.

3. Using your thumbs, slightly open the mouth by downward displacement of the chin.

Oropharyngeal airway (Guedel)

Airway adjuncts are often helpful and in some cases essential to maintain a patient’s airway. They should be used in conjunction with the manoeuvres mentioned above, as the position of the head and neck need to be maintained to keep the airway aligned.

An oropharyngeal airway is a curved plastic tube with a flange on one end that sits between the tongue and hard palate to relieve soft palate obstruction. It should only be inserted in unconscious patients as it is otherwise poorly tolerated and may induce gagging and aspiration.

To insert an oropharyngeal airway:

1. Open the patient’s mouth to ensure there is no foreign material that may be pushed into the larynx. If foreign material is present, attempt removal using suction.

2. Insert the oropharyngeal airway in the upside-down position until you reach the junction of the hard and soft palate, at which point you should rotate it 180°. The reason for inserting the airway upside down initially is to reduce the risk of pushing the tongue backwards and worsening airway obstruction.

3. Advance the airway until it lies within the pharynx.

4. Maintain head-tilt chin-lift or jaw thrust and assess the patency of the patient’s airway by looking, listening and feeling for signs of breathing.

Nasopharyngeal airway (NPA)

A nasopharyngeal airway is a soft plastic tube with a bevel at one end and a flange at the other. NPAs are typically better tolerated in patients who are partly or fully conscious compared to oropharyngeal airways. NPAs should not be used in patients who may have sustained a skull base fracture, due to the small but life-threatening risk of entering the cranial vault with the NPA.

To insert a nasopharyngeal airway:

1. Check the patency of the patient’s right nostril and if required (depending on the model of NPA) insert a safety pin through the flange of the NPA.

2. Lubricate the NPA.

3. Insert the airway bevel-end first, vertically along the floor of the nose with a slight twisting action.

4. If any obstruction is encountered, remove the tube and try the left nostril.

CPR

If the patient loses consciousness and there are no signs of life on assessment, put out a crash call and commence CPR.

Re-assessment

Make sure to re-assess the patient after any intervention.

Breathing

Clinical assessment

Observations

Review the patient’s respiratory rate:

- A normal respiratory rate is between 12-20 breaths per minute.

Review the patient’s oxygen saturation (SpO2):

- A normal SpO2 range is 94-98% in healthy individuals and 88-92% in patients with COPD who are at high risk of CO2 retention.

See our guide to performing observations/vital signs for more details.

Auscultation

Auscultate the chest to screen for evidence of respiratory pathology (e.g. coarse crackles may be present if the patient has developed aspiration pneumonia).

Investigations and procedures

These investigations should not delay the emergency management of stroke, including arranging neuroimaging and thrombolysis (if indicated).

Arterial blood gas

Take an ABG if indicated (e.g. low SpO2) to quantify the degree of hypoxia.

Chest X-ray

A chest X-ray may be indicated if abnormalities are noted on auscultation (e.g. reduced air entry, coarse crackles) to screen for evidence of aspiration pneumonia.

Interventions

Oxygen

Most stroke patients are not hypoxaemic. Evidence suggests high concentrations of supplemental oxygen should be avoided in stroke patients unless required to maintain oxygen saturations.

If the patient is conscious, sit them upright as this can also help with oxygenation.

Assisted ventilation

If your patient is unconscious and their respiratory rate is inadequate (too slow or irregular with big pauses), you can provide assisted ventilation through a bag-valve-mask (BVM): ventilate at a rate of 12-15 breaths per minute (roughly one every 4 seconds).

CPR

If the patient loses consciousness and there are no signs of life on assessment, put out a crash call and commence CPR.

Re-assessment

Make sure to re-assess the patient after any intervention.

Circulation

Clinical assessment

Observations

Review the patient’s heart rate:

- A normal resting heart rate (HR) can range between 60-99 beats per minute.

Review the patient’s blood pressure:

- A normal blood pressure (BP) range is between 90/60mmHg and 140/90mmHg but you should review previous readings to gauge the patient’s usual baseline BP.

- Hypertension can cause stroke through end-organ damage (this is known as a hypertensive emergency and tends to occur at BP >200 mmHg systolic)

- Hypotension can also cause stroke through global ischaemia, although this is less common

Capillary refill time

Capillary refill time may be normal or sluggish due to hypovolaemia.

Pulses and blood pressure

Assess the patient’s radial and brachial pulse to assess rate, rhythm, volume and character:

- An irregular pulse is associated with arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation. Atrial fibrillation is a common cause of thromboembolic stroke due to blood pooling and clotting in the heart.

Auscultation of the heart

Auscultation of the heart may reveal irregular heart sounds suggestive of atrial fibrillation.

Investigations and procedures

Intravenous cannulation

Insert at least one wide-bore intravenous cannula (14G or 16G) and take blood tests as discussed below.

See our intravenous cannulation guide for more details.

Blood tests

Collect blood tests after cannulating the patient including:

- FBC: as a baseline, and to look for underlying infection causing delirium (stroke mimic)

- U&Es: to look for renal impairment, as this will affect drug dosing

- LFTs: to check for any abnormal liver function, as this can affect clotting

- Coagulation: to check for risk of bleeding

- HbA1c: diabetes is a risk factor for stroke

- Cholesterol: raised cholesterol is a risk factor for stroke

ECG

Record a 12-lead ECG to identify atrial fibrillation.

Atrial fibrillation on an ECG appears as:

- Irregularly irregular rhythm

- Absent P waves

See our guides to recording and interpreting an ECG for more details.

Interventions

Intravenous fluids

Hypovolaemic patients require fluid resuscitation (the below guidelines are for adults):

- Administer a 500ml bolus of Hartmann’s solution or 0.9% sodium chloride (warmed if available) over less than 15 mins.

- Administer 250ml boluses in patients at increased risk of fluid overload (e.g. heart failure).

After each fluid bolus, reassess for clinical evidence of fluid overload (e.g. auscultation of the lungs, assessment of JVP).

Repeat administration of fluid boluses up to four times (e.g. 2000ml or 1000ml in patients at increased risk of fluid overload), reassessing the patient each time.

Seek senior input if the patient has a negative response (e.g. increased chest crackles) or if the patient isn’t responding adequately to repeated boluses (i.e. persistent hypotension).

See our fluid prescribing guide for more details on resuscitation fluids.

CPR

If the patient loses consciousness and there are no signs of life on assessment, put out a crash call and commence CPR.

Re-assessment

Make sure to re-assess the patient after any intervention.

Disability

Clinical assessment

Consciousness

In the context of a stroke, a patient’s consciousness level may be reduced if the stroke is large or affects the brainstem.

Assess the patient’s level of consciousness using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS).

Table 1. An overview of the Glasgow Coma Scale.

| Behaviour/domain | Response | Score |

| Eye-opening response | Eyes opening spontaneously | 4 |

| Eyes opening to sound | 3 | |

| Eyes open to pain | 2 | |

| No eye opening | 1 | |

| Verbal response | Orientated to time, place and person | 5 |

| Confused | 4 | |

| Inappropriate sounds | 3 | |

| Incomprehensible sounds (e.g. groaning) | 2 | |

| No response | 1 | |

| Motor response | Obeys commands for movement | 6 |

| Moves towards pain/localises to pain | 5 | |

| Withdraws away from pain | 4 | |

| Abnormal flexion/decorticate posturing | 3 | |

| Abnormal extension/decerebrate posturing | 2 | |

| No motor response | 1 |

Pupils

Assess the patient’s pupils:

- Inspect the size and symmetry of the patient’s pupils. Asymmetrical pupillary size may indicate intracerebral pathology.

- Assess direct and consensual pupillary responses which may reveal evidence of intracranial pathology.

Drug chart review

Review the patient’s drug chart for medications which may cause neurological abnormalities (e.g. opioids, sedatives, anxiolytics).

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS)

The NIHSS is a systematic, quantitative assessment tool for stroke-related neurological deficits. The higher the number, the greater the deficit and the bigger the stroke.

A score between 0 – 4 is given for the severity of each of the following:

- Level of consciousness

- Speech

- Ability to obey commands

- Horizontal gaze palsy

- Visual field loss

- Facial palsy

- Strength of arm movements and presence of drift

- Strength of leg movements and presence of drift

- Presence of ataxia

- Sensation changes

- Visual inattention

- Dysarthria

- Aphasia

Investigations

Blood glucose

Measure the patient’s capillary blood glucose level to screen for hypoglycaemia or hyperglycaemia. Hypoglycaemia is a common stroke mimic and must be excluded.

A blood glucose level may already be available from earlier investigations (e.g. ABG, venepuncture).

The normal reference range for fasting plasma glucose is 4.0 – 5.8 mmol/l.

Hypoglycaemia is defined as a plasma glucose of less than 3.0 mmol/l. In hospitalised patients, a blood glucose ≤4.0 mmol/L should be treated if the patient is symptomatic.

See our blood glucose measurement and hypoglycaemia guides for more details.

Imaging

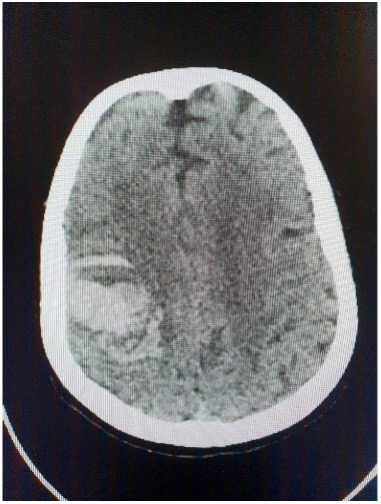

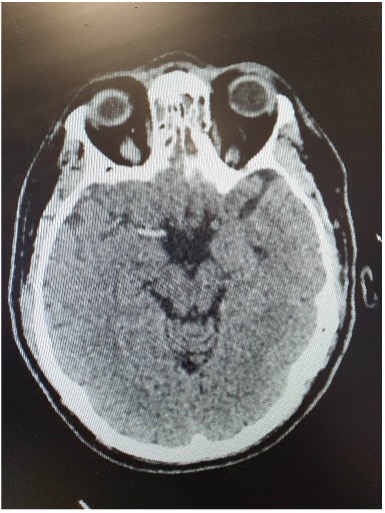

Request a CT head immediately in all cases of suspected stroke. A CT head is important to identify intracranial haemorrhage (as these patients must not receive thrombolysis).

In an ischaemic stroke, the CT head may be normal or show hypodensity. A CT may identify other intracranial pathology, including a space-occupying lesion.

In some patients who receive early imaging, the thrombus or embolus may be visible within the vessel. This appears as hyperdensity within the vessel (e.g. hyperdense middle cerebral artery).

See our guide to interpreting a CT head for more details.

Other relevant imaging includes:

- CT angiogram (aortic arch to the circle of Willis): looking for large vessel occlusion, vessel dissection or stenosis.

- MRI FAST head: sometimes performed in an acute setting, especially in wake-up strokes. Comparing different sequences can show if there is still perfusion and if someone would benefit from thrombolysis.

General interventions

Maintain the airway

Alert a senior immediately if you have any concerns about the consciousness level of a patient. A GCS of 8 or below warrants urgent expert help from an anaesthetist. In the meantime, you should re-assess and maintain the patient’s airway as explained in the airway section of this guide.

CPR

If the patient loses consciousness and there are no signs of life on assessment, put out a crash call and commence CPR.

Management of ischaemic stroke

Thrombolysis

Thrombolysis involves administering a thrombolytic agent (e.g. alteplase) to break down a clot. Thrombolysis can be used in patients with an ischaemic stroke who present within 4.5 hours of symptom onset.

Contraindications to thrombolysis include:

- Intracranial haemorrhage (a CT head must be performed to exclude a haemorrhage)

- Anticoagulation

- Stroke within the last 14 days

- Serious head injury within the last three months

- Known intracranial neoplasm, malignancy or aneurysm

- Intracranial or spinal surgery within the last three months

- Presence of a risk factor for increased bleeding or clotting disorder

- Rapidly improving symptoms

Example patient pathway for thrombolysis

It is important to follow local guidelines and pathways when managing patients with suspected stroke. An example of a patient pathway for a pre-hospital stroke is shown below:

- Pre-alert from the ambulance crew

- The patient arrives in ED and is taken to CT for neuroimaging

- Rapid focused history, examination and NIHSS score calculated

- If thrombolysis criteria are met, gain consent and establish intravenous access

- Check blood pressure (must be <185 systolic)

- Administer thrombolysis

- Monitor patient for reactions or deteriorating neurology

Mechanical thrombectomy

Mechanical thrombectomy involves the endovascular removal of a clot from a large cerebral vessel.

Criteria for mechanical thrombectomy include:

- Terminal internal carotid, middle cerebral artery (M1 or proximal M2) occlusion or basilar artery occlusion

- NIHSS score of 6 or more

- Presenting within 6 hours of onset

- No significant early ischaemic changes on imaging

If a patient does meet these criteria, a referral should be made to the closest mechanical thrombectomy centre.

Patients who do not fit the criteria for thrombolysis/thrombectomy

For patients who do not fit the criteria for acute management (thrombolysis/thrombectomy), general medical management involves:

- Aspirin 300mg for two weeks, followed by clopidogrel 75mg lifelong

- Identification and management of atrial fibrillation (including anticoagulation): the timing of starting anticoagulation will depend on the size of the stroke

Management of intracranial haemorrhage

General management of an intracranial haemorrhage includes:

- Anticoagulant reversal: discuss with haematology if required

- Blood pressure lowering: aim for BP < 140 mmHg systolic (if <6 hours of onset) or < 180 mmHg systolic (if >6 hours of onset). Use labetalol 10mg IV, then consider GTN infusion.

- Referral: consider referral to neurosurgery for advice regarding potential surgical intervention.

Re-assessment

Make sure to re-assess the patient after any intervention.

Exposure

It may be necessary to expose the patient during your assessment: remember to prioritise patient dignity and conservation of body heat.

Clinical assessment

Begin by asking the patient if they have pain anywhere, which may be helpful to guide your assessment.

Inspection

Inspect the patient’s skin for evidence of bruising, which may indicate an underlying clotting abnormality (e.g. disseminated intravascular coagulation).

Assess the patient’s calves for erythema, swelling and tenderness which may suggest a deep vein thrombosis.

Review the output of the patient’s catheter (if present).

Temperature

Review the patient’s body temperature:

- A normal body temperature range is between 36°c – 37.9°c.

- A temperature of >38°c is most commonly caused by infection (e.g. sepsis).

- A temperature < 36°c may also be caused by sepsis or cold exposure (e.g. drowning, inadequate clothing outside).

- Consider warming (e.g. Bair Hugger™) in hypothermia (seek senior input).

Investigations

Further investigations will depend on the clinical context and may be required to exclude stroke mimics.

Interventions

Further interventions will depend on the clinical context and may be required to manage stroke mimics.

CPR

If the patient loses consciousness and there are no signs of life on assessment, put out a crash call and commence CPR.

Re-assessment

Make sure to re-assess the patient after any intervention.

Reassess ABCDE

Re-assess the patient using the ABCDE approach to identify any changes in their clinical condition and assess the effectiveness of your previous interventions.

Deterioration should be recognised quickly and acted upon immediately.

Seek senior help if the patient shows no signs of improvement or if you have any concerns.

Support

You should have another member of the clinical team aiding you in your ABCDE assessment, such a nurse, who can perform observations, take samples to the lab and catheterise if appropriate.

You may need further help or advice from a senior staff member and you should not delay seeking help if you have concerns about your patient.

Use an effective SBAR handover to communicate the key information effectively to other medical staff.

Next steps

Well done, you’ve now stabilised the patient and they’re doing much better. There are just a few more things to do…

Take a history

Revisit history taking to identify risk factors for stroke and explore relevant medical history. If the patient is confused you might be able to get a collateral history from staff or family members as appropriate.

See our history taking guides for more details.

Review

Review the patient’s notes, charts and recent investigation results.

Review the patient’s current medications and check any regular medications are prescribed appropriately.

Document

Clearly document your ABCDE assessment, including history, examination, observations, investigations, interventions, and the patient’s response.

See our documentation guides for more details.

Discuss

Discuss the patient’s current clinical condition with a senior clinician using an SBAR style handover.

Questions which may need to be considered include:

- Are any further assessments or interventions required?

- Does the patient need a referral to HDU/ICU?

- Does the patient need reviewing by a specialist?

- Should any changes be made to the current management of their underlying condition(s)?

Handover

The next team of doctors on shift should be made aware of any patient in their department who has recently deteriorated.

Reviewers

Dr Katharine Arnold

Geriatric medicine registrar

Dr Emma Broughton

Emergency medicine registrar

References

- Stroke UK. Stroke statistics. 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- NHS. Stroke. 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- NICE. Stroke and transient ischaemic attack in over 16s: diagnosis and initial management, 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Royal College of Physicians. Stroke Guidelines, 2016. Available from: [LINK]