- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

This testicular examination OSCE guide provides a clear step-by-step approach to examining a patient’s testicles and penis.

Introduction

Wash your hands and don PPE if appropriate.

Introduce yourself to the patient including your name and role.

Confirm the patient’s name and date of birth.

Briefly explain what the examination will involve using patient-friendly language: “Today I need to carry out an examination of your genitals, this will involve me examining your penis, testicles and the surrounding region.”

Explain the need for a chaperone: “One of the ward staff members will be present throughout the examination, acting as a chaperone, would that be ok?”

Gain consent to proceed with the examination: “Do you understand everything I’ve said? Do you have any questions? Are you happy for me to carry out the examination?”

Explain to the patient that they’ll need to remove their underwear and lie on the clinical examination couch, covering themselves with the sheet provided. Provide the patient with privacy to undress and check it is ok to re-enter the room before doing so.

Ask the patient if they have any pain before proceeding with the clinical examination.

Inspection

Penis, groin and abdomen

Inspect the patient’s penis, groin and abdomen for relevant clinical signs:

- Skin changes: bruising, swelling, warts (human papillomavirus) and erythema.

- Scars: note any scars on the penis (e.g. circumcision) or in the inguinal region (e.g. inguinal hernia repair, orchidopexy).

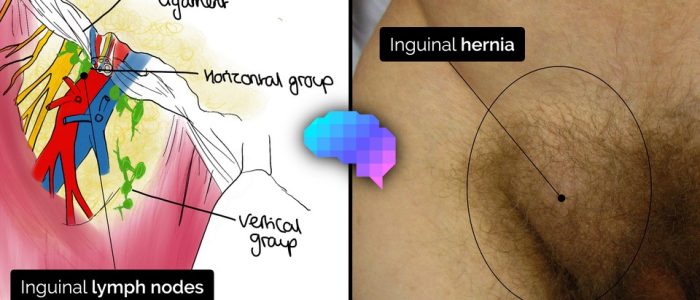

- Masses: note any masses in the inguinal region (e.g. inguinal hernia, lymphadenopathy, undescended testicle) or on the penis (e.g. chancre in primary syphilis).

Scrotum and perineum

Ask the patient to lift their penis out of the way to allow you to closely inspect the scrotum and perineum for relevant clinical signs:

- Skin changes: warts (human papillomavirus), erythema (e.g. cellulitis, fungal infection).

- Scars: may indicate previous surgery (e.g. vasectomy, testicular fixation).

- Masses: note any lumps associated with the scrotum (e.g. testicular cancer) or the perineum (e.g. abscess).

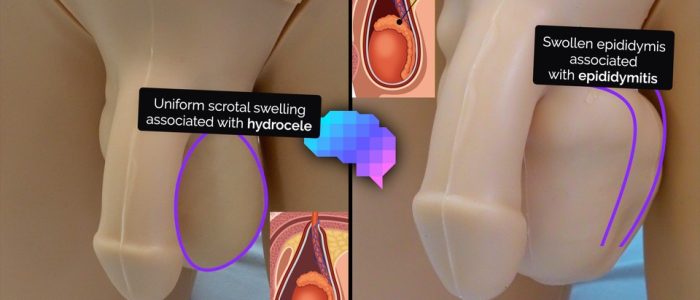

- Swelling: note any swelling of the scrotum (e.g. hydrocele, oedema) and look for associated erythema (e.g. cellulitis).

- Bruising: may indicate local trauma.

- Necrotic tissue: consider Fournier’s gangrene (necrotising fasciitis of the external genitalia and/or perineum) which is often first noted on the perineum.

Palpation

Penis

Examine the penis for relevant clinical signs:

- Retract the foreskin (if the patient is not circumcised) and check for phimosis (narrowing of the foreskin). If you are unable to retract the foreskin, ask the patient to try and do this themselves.

- Open the urethral meatus to assess patency.

- Inspect the glans for abnormalities (e.g. ulcers, warts, discharge, scarring).

- Replace the foreskin once examined to prevent paraphimosis (a condition in which the retracted foreskin obstructs venous return from the glans, resulting in painful swelling of the glans).

Testicles

If abnormalities have been identified during the process of inspection or the patient is concerned about a particular testicle, perform an examination of the ‘normal’ testicle first. Ask the patient to report any pain or discomfort they experience during the examination.

Testicular palpation

Use both of your thumbs and index fingers to gently palpate the whole testicle, whilst your remaining fingers remain placed behind the testicle to immobilise it.

Palpation of the testicle involves a gentle rubbing motion between your thumb and index finger to methodically examine the whole body of the testicle.

If you are unable to locate a testicle, palpate along the path of the inguinal ligament for an undescended testicle (if the patient also has a scar in their inguinal region this would suggest a previous orchidectomy or orchidopexy).

Assessing a scrotal mass

If a scrotal mass is identified, assess the following characteristics:

- Site: assess the mass’s location in relation to other anatomical structures. In particular, assess the mass’s anatomical relationship to the testicle (e.g. part of the testicle vs separate from it).

- Size: assess the size of the mass.

- Shape: assess the mass’s borders to determine if they feel regular or irregular.

- Consistency: determine if the mass feels soft (e.g. cyst), hard (e.g. malignancy, epididymis, testicle) or ‘like a bag of worms’ (e.g. varicocele).

- Tenderness: tenderness may indicate infective and/or inflammatory aetiology (e.g. epididymo-orchitis).

- Fluctuance: hold the mass by its sides and then apply pressure to the centre of the mass with another finger. If the mass is fluid-filled (e.g. cyst) then you should feel the sides bulging outwards.

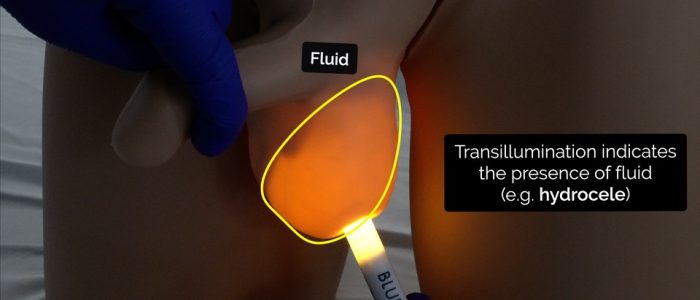

- Transillumination: apply a light source to the mass, if it is illuminated it suggests the mass is fluid-filled (e.g. hydrocele). A hydrocele can sometimes be so large that you will not be able to palpate the testicle contained within it.

- Cough impulse: the presence of a cough impulse is suggestive of an underlying inguinal hernia or varicocele.

- Ability to get above the lump: the inability to get above the mass during palpation is suggestive of an inguinal hernia (you should be able to get above a scrotal mass).

Epididymis

Palpate the epididymis which is located at the posterior aspect of the testicle: tenderness is indicative of epididymitis (e.g. chlamydia).

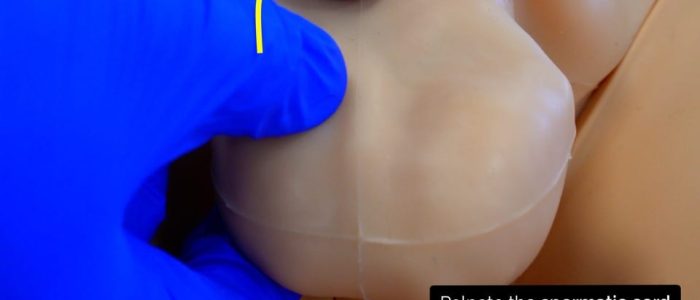

Spermatic cord

The spermatic cord is the cord-like structure in males formed by the vas deferens and surrounding tissue that runs from the deep inguinal ring down to each testicle.

Begin palpation of the spermatic cord from the superior aspect of the testicle using your thumb and index finger. The spermatic cord should be palpable connecting to the testicle at this region. Palpate along the cord assessing for masses (e.g. spermatocele) and tenderness.

Prehn’s test

Prehn’s test is used to differentiate testicular pain caused by acute epididymitis and testicular torsion.

The test involves elevating the testes to assess the impact on testicular pain. A reduction in testicular pain is associated with epididymitis.

Although this test can provide some clinical value it is inferior to Doppler ultrasound when trying to rule out testicular torsion.

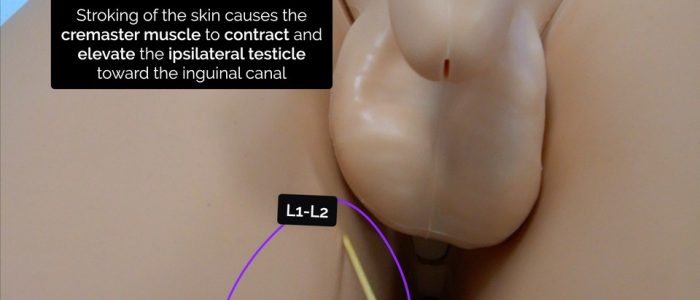

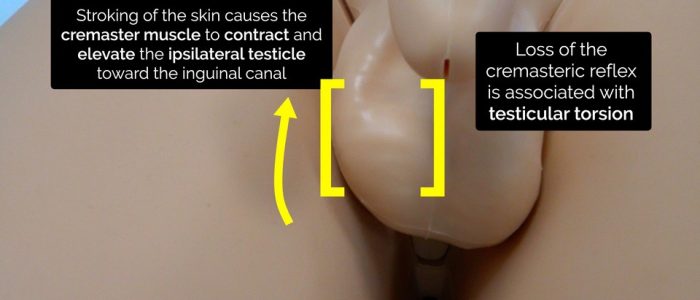

Cremasteric reflex

The cremasteric reflex is a superficial reflex which is elicited when the inner part of the thigh is stroked. Stroking of the skin causes the cremaster muscle to contract and pull up the ipsilateral testicle toward the inguinal canal. Loss of the cremasteric reflex is associated with testicular torsion, but it should not be relied upon in isolation for ruling the condition in or out (a Doppler ultrasound should always be performed).

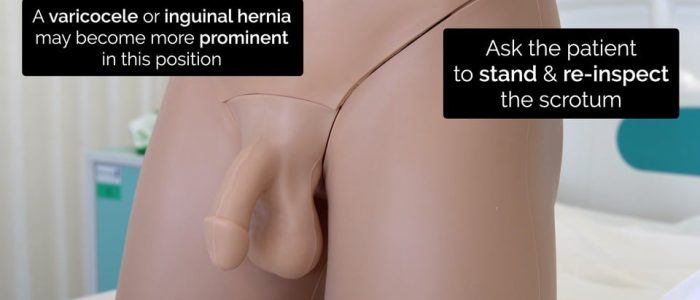

Assessment of the scrotum whilst the patient is standing

At the end of the examination, ask the patient to stand to allow you to re-assess the scrotum.

Inspect and palpate the posterior scrotum for evidence of varicocele (a palpable mass that feels like a ‘bag of worms’) or a hernia (a mass which you cannot get above).

To complete the examination…

Explain to the patient that the examination is now finished and provide them with privacy to get dressed.

Thank the patient for their time.

Dispose of PPE appropriately and wash your hands.

Summarise your findings.

Example summary

“Today I examined Mr Smith, a 64-year-old male. On general inspection, the patient appeared comfortable at rest and there were no objects or medical equipment around the bed of relevance.”

“On inspection, there were no abnormalities identified, however, on palpation, there was a 1cm smooth solid mass noted in the left side of the scrotum, separate from the testicle. The mass was fluctuant, non-tender and transilluminated. I was able to get above the mass and there was no cough impulse.”

“In summary, these findings are consistent with an epididymal cyst or a spermatocele.”

“For completeness, I would like to perform the following further assessments and investigations.”

Further assessments and investigations

Suggest further assessments and investigations to the examiner:

- Full abdominal examination

- Ultrasound scan of the testicles

Urology conditions overview

Hydrocele

- Hydrocele involves an accumulation of fluid in the tunica vaginalis which can be congenital or acquired. Congential hydrocele is due to a patent processus vaginalis (PPV).

- The testicle should be palpable within the hydrocele sac and the mass should transilluminate.

- If the hydrocele is large, the testicle may be difficult to palpate.

Epididymal cyst

- An epididymal cyst is a benign, smooth, extra-testicular, spherical cyst that is most commonly located in the head of the epididymis.

- Typical clinical findings include a fluctuant mass, separate from the testicle that transilluminates.

Spermatocele

- A spermatocele is a benign, smooth, extra-testicular, spherical cyst in the head of the epididymis or spermatic cord (there is no way to clinically differentiate a spermatocele from an epididymal cyst).

- The cystic fluid contains sperm (unlike an epididymal cyst).

- Typical clinical findings include a fluctuant mass, separate from the testicle that transilluminates.

- Spermatoceles most commonly develop in patients post-vasectomy.

Varicocele

- A varicocele is an abnormal dilatation of the testicular veins in the pampiniform venous plexus, caused by venous reflux.

- Typical clinical findings include a posterior scrotal mass that feels like ‘a bag of worms’ which is more apparent when the patient is standing. A cough impulse may also be present.

- If of recent onset on the left side a renal tract ultrasound should be performed to rule out renal cancer as the left gonadal vein drains into the left renal vein.

Epididymitis

- Epididymitis involves the progressive painful swelling of the epididymis +/- testicle (epididymo-orchitis).

- If the patient is aged under 35, it is likely due to a sexually transmitted infection (e.g. chlamydia).

- If the patient is aged over 35, urinary pathogens such as E. Coli are the most common cause.

Testicular torsion

- Testicular torsion involves the twisting of the spermatic cord resulting in a sudden loss of testicular blood supply.

- Typical clinical features include the sudden onset of severe testicular pain, scrotal erythema and a swollen retracted testicle.

- If there is suspicion of testicular torsion a scrotal ultrasound should be considered if there is diagnostic uncertainty. Surgical exploration is commonly warranted.

Testicular malignancy

Key points:

- Testicular malignancy most commonly affects males aged between 20-40 years old.

- In the early phase of the disease, there are few, if any, systemic symptoms with the only clinical feature being a solitary solid testicular mass.

- If there is suspicion of testicular malignancy patients should have an urgent ultrasound scan of the testicles, chest x-ray and tumour markers checked (Beta-HCG, Alpha-fetoprotein and Lactate Dehydrogenase [LDH]).

- Treatment is most commonly inguinal orchidectomy.

Orchidopexy

Key points:

- An orchidopexy is an operation performed in children for undescended testicles where the testicle is brought down from the inguinal canal into the scrotum.

- Undescended testicles can increase the risk of testicular malignancy if left untreated.

Unilateral testicular atrophy

- Unilateral testicular atrophy involves the shrinkage of one testicle which may occur following mumps, vascular compromise (e.g. missed testicular torsion) or surgery (e.g. orchidopexy or inguinal hernia repair).

Bilateral testicular atrophy

- Bilateral testicular atrophy is suggestive of primary or secondary hypogonadism.

- Further investigations involve assessment of secondary sexual characteristics and hormonal abnormalities as well as ruling out anabolic steroid use.

Phimosis

- Phimosis involves the narrowing of the distal foreskin leading to an inability to retract it.

- It is most commonly associated with the chronic inflammatory condition balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO).

- Phimosis is physiological in most children with only 1% of children having persisting phimosis by the age of 16.

- If phimosis is severe, it may require circumcision.

Paraphimosis

- Paraphimosis typically develops when a patient’s foreskin is left retracted (typically after catheterisation) resulting in impaired venous return, venous hypertension and eventually impaired arterial supply to the glans.

- Typical clinical features involve a swollen, oedematous glans/foreskin and significant pain.

- Urgent correction by manually replacing the foreskin is required to restore normal venous drainage and arterial supply.

Reviewer

Mr Kenneth Mackenzie

Urology Registrar

References

- Drvgaikwad. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Paraphimosis. Licence: CC BY.

- Pygmalion. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Chancre. Licence: CC BY.

- Fisch12. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Varicocele. Licence: CC BY.