- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Total knee replacement (TKR) or total knee arthroplasty (TKA) refers to the resurfacing/replacement of the articular surfaces of the knee joint to restore function in the arthritic knee.

This is commonly done through the replacement of diseased or dysfunctional articular cartilage with metal prostheses over the femur and tibia, with a plastic spacer between metal surfaces. The procedure may include resurfacing the patella.1

Indications for total knee replacement

TKR is usually performed on patients with end-stage osteoarthritis of the knee joint, where conservative treatment has failed.

Other indications for total knee replacement include:

- Where the knee joint has become severely damaged due to systemic rheumatic conditions (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis)

- Trauma (new or old) where the damaged bones cannot be reconstructed

- The reconstruction of the distal femur and proximal tibia in bony tumours (either primary or secondary metastases)

The normal active range of motion of the knee is 00 – 1400 of knee flexion, although this varies with age and gender. Knee arthritis causes a progressive deterioration of range of motion and usually worsens with disease progression.2

In patients with degenerative osteoarthritis, TKR surgery is commonly undertaken as an elective in-patient (or as a day case in an increasing number of cases) procedure and is generally low-risk, though there are potential complications.

Total knee replacement constitutes one of the most common elective operations in the UK therefore an understanding of the anatomy, risks and management of patients undergoing total knee replacement is relevant to all clinicians.3

Osteoarthritis of the knee

Osteoarthritis of the knee is the indication for 97% of primary knee replacements.4

Aetiology

Osteoarthritis occurs due to the combined mechanical degeneration and biological events that together destabilise the normal degradation and synthesis of articular cartilage.5 This form of chronic, progressive joint degeneration can be explained in terms of ‘wear and tear‘ to patients.

The exact underlying cause, however, is more complex. Osteoarthritis may be thought of more as a form of dysfunctional ‘wear and repair’ over time, where mechanical changes disrupt the functional homeostasis of the joint.6 Weight-bearing joints, such as the knee and hip, are most commonly affected.

The pathogenesis of osteoarthritis involves three main processes:

- Mechanical ‘wear and tear’

- Structural degeneration

- Joint inflammation

The interactions of these three processes give rise to the joint damage we attribute to osteoarthritis:6

- Overuse of weight-bearing joints and activity results in the release of cytokines and chemokines in the affected joint synovium.

- Metalloproteinases in the joint matrix are activated, causing the breakdown of the extracellular matrix.

- Stress to the cartilage results in the promotion of chondrocytes, which produce matrix-degrading enzymes.

- In late-stage disease, chondrocytes undergo apoptosis.

These steps lead to the characteristic inflammatory features of osteoarthritis visible on X-ray.

X-ray changes in osteoarthritis

The common changes found on X-ray imaging with osteoarthritis can be memorised using the mnemonic ‘LOSS’:

- Loss of joint space

- Osteophytes

- Subchondral sclerosis

- Subchondral cysts

More details about interpretation and examples of musculoskeletal X-rays can be found in the Geeky Medics guide to musculoskeletal X-ray interpretation.

The earliest feature of osteoarthritis on light microscopy is chondral fibrillation, with progressively deeper tears in the articular cartilage visible as the disease progresses. Cartilage loss and remodelling follow.6

Later histological features of osteoarthritis see subchondral bone thickening and sclerosis, in addition to articular bone outgrowths, called osteophytes forming. Eventually, all cartilage erodes, resulting in bone-on-bone articulation at the joint. The rubbing of bone on bone causes intense pain and is incredibly debilitating.

In the knee, the medial compartment is typically affected first, due to the natural valgus position of most knees.

Osteoarthritis can be divided into primary and secondary:

- Primary osteoarthritis: degeneration of the articular cartilage without an underlying cause, the pathophysiology of primary osteoarthritis is outlined above.

- Secondary osteoarthritis: the consequence of abnormal forces across the joint (such as following minor trauma to the knee), or due to pathology of the articular cartilage, commonly caused by rheumatic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis.7

For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to osteoarthritis.

Anatomy

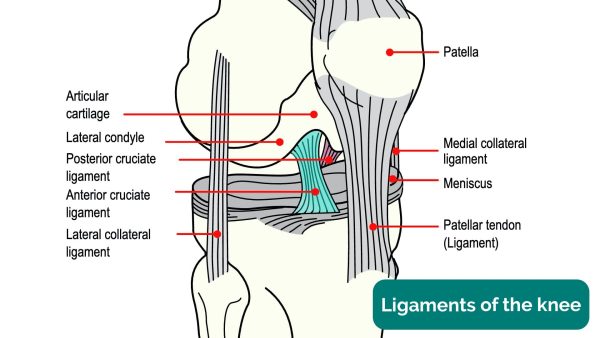

The knee joint is made up of two separate joints:

- The tibiofemoral joint: medial and lateral

- The patellofemoral joint

Each joint is lined with smooth articular (hyaline) cartilage.

The tibiofemoral joint transfers body weight from the femur to the tibia and acts as the primary weight-bearing joint of the knee. The patellofemoral joint acts as an interface between the patella and femur, with the patella acting as a pulley to transmit forces during knee extension.

The fibula runs alongside the tibia, and though not involved in the knee joint provides an attachment surface for muscles and ligaments.

Knee joint stability is provided on the coronal plane by the medial and lateral collateral ligaments, with medial and lateral menisci acting as shock absorbers on the tibial plateau. The anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments cross one another attaching at the lateral and medial femoral condyles, anchored at the medial tibial spine and posterior surface of the tibia respectively. The ACL and PCL resist anterior and posterior tibial translation respectively.9

For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to the anatomy of the knee joint.

Clinical features

Typical clinical features of knee osteoarthritis include:9,10

- Less than 30 minutes of morning knee stiffness resolving with activity

- Chronic progressive joint pain

- Mild joint swelling

- Crepitations (clicking sounds) on the movement of the joint

- Knee pain worsened by standing or weight bearing (e.g. climbing stairs)

Advanced osteoarthritis may also feature joint instability and locking.

When performing a knee examination, typical findings may include:

- Mild knee effusion indicated on patellar tap or swipe tests

- Atrophy of muscles around the knee joint (predominantly the quadriceps)

- A restrictive active and passive range of movement

- Pain on movement of the knee

Oxford Knee Score

The Oxford Knee Score is a widely used patient-reported scoring system used to evaluate the severity of osteoarthritis of the knee.

Imaging

Several grading systems are used to evaluate the severity of OA in knee radiographs. The most common is the Kellgren and Lawrence (KL) grading system.

Surgical management of knee osteoarthritis

The initial management of knee osteoarthritis should be conservative and focused on relieving the mechanical load on the knee to slow the progression of the disease.11

TKA is the end point of the long-term management of osteoarthritis when conservative measures no longer provide any relief of symptoms of pain and impaired mobility.

The primary indication for joint replacement is pain, rather than a loss of function, though both do indicate surgery. It is important patients be made aware of the risks associated with surgery, and then referred for orthopaedic evaluation for knee replacement. In consultation, patients should be made aware of the long waiting times (in the United Kingdom) for elective joint replacement.3

Total knee replacement procedure

Approaches

Different approaches can be undertaken in TKA, depending on the natural position of the knee, which varies from patient to patient.

The vast majority of TKAs are performed via a medial parapatellar approach. This involves a vertical 15cm incision across the patellar aspect of the knee. Alternatively, a lateral approach can be used for knees which are naturally more valgus (‘knock-kneed’). Minimally invasive joint replacement is also becoming more popular. This article will focus on the medial parapatellar approach.12

Preoperative preparation

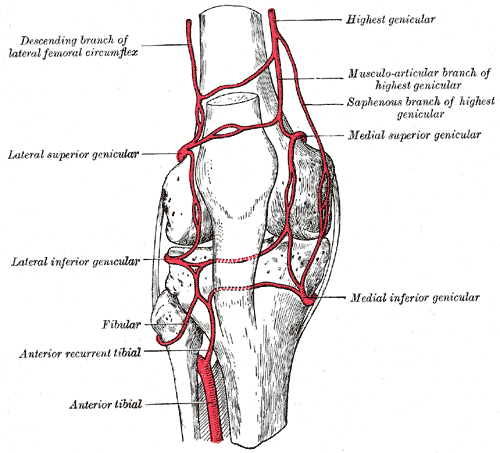

The majority of the blood supply to the skin over the knee comes from the saphenous artery and descending geniculate artery, on the medial aspect of the knee.

The patella is the first bony landmark encountered on the medial parapatellar approach. It is separated from the skin by the prepatellar bursa, a fluid-filled sac covering the patella. The patella’s blood supply is different from the blood supply of the skin surrounding the knee and arises from a plexus of arteries including the genicular arteries and anterior tibial recurrent artery.

The skin around the knee is innervated by branches of the saphenous nerve anteriorly and laterally.

A branch of the saphenous nerve (infrapatellar branch) is typically cut through with vertical skin incisions (particularly anterior and anteromedial incisions), resulting in an area of transient or permanent cutaneous hypoesthesia on the skin over the anterolateral knee. Patients should be made aware of this possible complication of surgery when consented for the procedure.12

Prophylactic antibiotics should be administered 30 minutes before applying a tourniquet to the target leg, in addition to anticoagulation. Most elective procedures are undertaken under sedation, with a guided femoral nerve block.

Patient positioning

The patient is supine for the operation, with a tourniquet applied to the mid-thigh of the target leg to mitigate blood loss. The foot is placed on a footrest, and a bolster is used to keep the leg straight and prevent any external hip rotation. The leg is draped and shaved if appropriate, then swabbed. Sterile stockinettes are then placed over the leg.

It is important to note that using a tourniquet may be contraindicated in patients with peripheral vascular disease and may exacerbate symptoms in patients with peripheral neuropathy. 12

The knee is then placed in 90-degrees of flexion. Anatomical landmarks are then marked over the anterior aspect of the knee.

Summary of operative steps13

A 15cm vertical skin incision is made over the patella, in keeping with the medial parapatellar approach. A new blade is then used to dissect through the anterior border of the quadriceps, patella, and medial aspect of the patellar tendon.

Skin flaps are then retracted, the patella everted, and a medial arthrotomy is performed with a large blade. The knee is then extended in what is called the medial release, and the arthrotomy is completed. The knee is then returned to flexion. The infrapatellar fat pad and ACL are resected, and the tibia is externally rotated.

The articular surface and a small amount of subchondral bone from the tibia and the femur are then resected, it is up to the surgeon to choose whether to resect the tibia or the femur first. The primary aim is to remove adequate bone to replace it with metallic components and plastic whilst ensuring that the knee is stable throughout the range of movement.

The tibial cutting jig is now fixed in place, and alignment can be adjusted depending on how varus/valgus a patient’s knee is. Pins are used to fix the jig in place. A saw is then passed through a slot in the jig, and the diseased articular cartilage is resected.

A jig is placed onto the distal femur (via a rod into the medullary canal), and three cuts are made, resection of the distal femur, resection of anterior and posterior portions of the femur, and finally chamfer cuts.

Prosthetic femoral components are now trialled and are tapped on, ensuring the prosthetic is flush with the femur.

The tibial tray is now inserted. The knee can be extended to aid this, then returned to flexion. The range of motion of the knee is then assessed and evaluated. At this point, additional bone may be resected, or the implant augmented as required.

If satisfied with the knee’s range of motion and patellar tracking, the focus can turn to patellar resurfacing. Any diseased patella is resected, any osteophytes removed, and a prosthetic button is inserted.

Holes are then drilled into the distal femur and proximal tibia, and final box cuts are made. All surfaces are then irrigated and tools are set up for cementing. Gloves are changed at this point.

Cement is then used to fix implants in place, implants are hammered in place, and any excess cement is scraped away. The patella is cemented. The range of motion of the knee is assessed again and surfaces are irrigated.

Interrupted sutures are used to close the patella tendon. Dermal and skin closures are then performed.

Complications

The success rate of primary TKA is excellent, with over 82% of total knee replacements still viable after 25 years.14

The complication rate of modern surgery is also low, with fewer than 2% of patients experiencing a complication.1

Complications following TKA include:15

- Urinary tract infection (1.49%)

- Deep vein thrombosis (1.34%)

- Superficial wound infection (0.79%)

- Pulmonary embolism (0.78%)

- Postoperative sepsis (0.44%)

- Deep joint infection (0.30%)

- Cerebrovascular accident (0.11%)

- Peripheral nerve injury (0.10%)

Other complications include postoperative stiffness, joint swelling and periprosthetic fracture, and joint prosthesis loosening.

Septic arthritis

Joint infection (septic arthritis) after knee replacement surgery is a rare but serious complication. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, and of increasing age are at the greatest risk.

Patients should engage in a course of physiotherapy following joint replacement to mitigate any pain or stiffness postoperatively and to improve joint range of motion. Most patients should anticipate achieving 90 degrees of active knee flexion (or more), full knee extension and minimal to no pain and swelling 4-6 weeks postoperatively.16

About one in five patients experience residual symptoms, and although successful in relieving pain and improving function, TKA surgery is often associated with patient dissatisfaction.

Patient expectations should be managed, and patients should be informed of the limited recovery of proprioception, postural control and strength in the ‘new’ joint in addition to a reduced range of motion compared to their previous function.17

Key points

- TKR is a common elective surgical procedure involving the resurfacing/replacement of the articular surfaces of the knee joint.

- The main indication for TKR is severe osteoarthritis of the knee. Other indications include the reconstruction of the knee after trauma or osteosarcoma.

- The principal benefits are the restoration of function and pain elimination to improve quality of life, with pain refractory to conservative treatment being the main indication.

- The most common surgical approach is the parapatellar approach.

- Key operative risks include iatrogenic soft tissue, bone, and neurovascular injury.

- The most common postoperative complications are urinary tract infections, deep venous thrombosis, superficial wound infections, and pulmonary embolism.

Reviewer

Professor Hemant Pandit

Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery

University of Leeds

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- AAOS. Total Knee Replacement – Orthoinfo. 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- Khatri K, Bansal D, Rajpal K. Management of Flexion Contracture in Total Knee Arthroplasty. InKnee Surgery-Reconstruction and Replacement 2020 Apr 22. InTechOpen

- Ben-Shlomo Y, Blom A, Boulton C, et al. The National Joint Registry 18th Annual Report 2021 [Internet]. London: National Joint Registry; 2021 Sep. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on joint replacement surgery volumes and waiting lists.

- NHS Scotland. Knee Replacement Surgery. 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- Hunter, David J, and David T Felson. Osteoarthritis. BMJ, vol 332, no. 7542, 2006, pp. 639-642. BMJ,

- Mora, Juan C et al. Knee Osteoarthritis: Pathophysiology And Current Treatment Modalities. Journal Of Pain Research, Volume 11, 2018, pp. 2189-2196. Informa UK Limited

- Physiopedia. Knee Osteoarthritis. 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- Hsu, H., & Siwiec, R. M. (2022). Knee Osteoarthritis. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- Physiopedia. Knee. 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- NICE CKS. Osteoarthritis. 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- NICE. Osteoarthritis: care and management. 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- Lotke, Paul A. Knee Arthroplasty. 3rd ed., Raven Press, 1995, pp. 1-19.

- Racy, Malek. Training Videos., 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- Evans, Jonathan T et al. “How Long Does A Knee Replacement Last? A Systematic Review And Meta-Analysis Of Case Series And National Registry Reports With More Than 15 Years Of Follow-Up”. The Lancet, vol 393, no. 10172, 2019, pp. 655-663. Elsevier BV,

- Belmont, Philip J. et al. “Thirty-Day Postoperative Complications And Mortality Following Total Knee Arthroplasty”. Journal Of Bone And Joint Surgery, vol 96, no. 1, 2014, pp. 20-26. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health)

- Gonzalez Della Valle A, Leali A, Haas S. Etiology and Surgical Interventions for Stiff Total Knee Replacements. HSS Journal. 2007;3(2): 182-189

- Chan A, Jehu D, Pang M. Falls After Total Knee Arthroplasty: Frequency, Circumstances, and Associated Factors – A Prospective Cohort Study. Physical Therapy. 2018;98(9): 767-778.

- Labek, G. et al. “Revision Rates After Total Joint Replacement”. The Journal Of Bone And Joint Surgery. British Volume, vol 93-, no. 3, 2011, pp. 293-297. British Editorial Society Of Bone & Joint Surgery,

Image references

- Figure 1. OpenStax. Knee Ligaments. Adapted by Geeky Medics. April 2013. License: [CC BY 4.0]

- Figure 2. Gray, Henry. Fig. 552 – Gray’s Anatomy 20th Edition. 1918. License: [Public domain]

- Figure 3. Rama. Prothese-genou. License: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 4. RaveDave. Knee Replacement. License: [CC BY-SA]