- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are rare, acute, and potentially fatal skin reactions which cause sheet-like skin detachment and mucosal loss.1

Both SJS and TEN are believed to be variants of the same condition that can be differentiated by the degree of skin and mucous membrane involvement:2,3

- SJS has <10% total body surface area (TBSA) involvement

- SJS/TEN overlap has 10% to 30% TBSA involvement

- TEN has >30% TBSA involvement

SJS/TEN are caused by an immune-complex-mediated hypersensitivity reaction and are mostly, but not always caused by medications.1,2

The incidence of SJS is estimated at 1-6 cases/million person-years, and 0.4-1.2 cases/million person-years for TEN.4

Aetiology

SJS/TEN results from an immune reaction to foreign antigens, although the pathophysiology is complex and still not fully understood.2

Both SJS and TEN are characterised by the detachment of the epidermis from the papillary dermis at the epidermal-dermal junction, manifesting as dusky macular erythema, followed by blistering resulting from keratinocyte apoptosis.5

Approximately 75% of SJS/TEN are caused by medications and 25% by infections and other causes.2

SJS/TEN usually develops in individuals who have started taking a new drug for 1 day to 1 month.3

Risk factors

Risk factors for SJS/TEN include:

- Antibiotics: the greatest risk is posed by trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and other sulphonamide antibiotics, as well as aminopenicillins, quinolones and cephalosporins.6

- Anticonvulsant medications: most commonly carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, lamotrigine and valproic acid.4

- Recent infections: Mycoplasma pneumonia has been associated with the development of SJS.7 Viral infections include herpes, Epstein-Barr virus, and cytomegalovirus.7

- Other medications: antifungals, antivirals, antiretrovirals, analgesics (e.g. paracetamol), NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, antimalarials, corticosteroids, azathioprine, sulfasalazine, allopurinol, tranexamic acid, psychotropic agents and retinoids.8

- Systemic lupus erythematosus: likely caused by immune reactions with the medicines used to treat SLE, such as corticosteroids and isoniazid.4

- HIV/AIDS: SJS/TEN is more common in individuals with HIV/AIDS, estimated at 1-2/1000 in Canada.2 Prophylactic use of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole to prevent Pneumocystic jirovecii pneumonia contributes to increased risk.9

- Radiotherapy: oncology patients are immunocompromised from the disease process and chemotherapy. SJS/TEN is seen most frequently with recent anticonvulsant medicine during cranial irradiation.10

- Genetic predisposition: the presence of particular HLA alleles have been found to be associated with SJS/TEN.11 HLA B1502 and HLA B1508 among the Han Chinese are associated with SJS/TEN in reaction to carbamazepine and allopurinol, respectively.2 The US Food and Drug Administration recommends testing all people of Asian heritage before prescribing these medications.12

Clinical features

History

Typical symptoms of SJS/TEN include:1,13,14

- Prodromal ‘flu-like’ illness for several days before the rash appears

- Fever >39℃

- Sore throat, odynophagia, dysphagia

- Cough, runny nose

- Sore red eyes, conjunctivitis

- Arthralgia, malaise

- A painful skin rash develops, starting at the trunk and extending rapidly over hours to days onto the face and limbs with blistering.

- Mucosal ulceration (e.g. eyes, lips, mouth, genitals)

Other important areas to cover in the history include:

- Drug history: most importantly newly commenced medications.

- Recent infections (e.g. mycoplasma pneumonia, Epstein-Barr virus)

- Past medical history (e.g. HIV, systemic lupus erythematosus, cancer)

Clinical examination

Typical clinical findings in SJS/TEN include:1,8

- A tender dusky erythematous skin rash develops initially in clusters of macules and progresses to blistering (figure 1).

- The blisters then merge to form sheets of skin detachment (desquamation – figure 2) exposing, red, oozing dermis (figure 3).

- The Nikolsky sign is positive, meaning the epidermal layer easily sloughs off when pressure is applied to the affected area.

- The maximum extent is usually reached by four days, but may also progress at a slower rate.

- Mucosal involvement (figure 4) is prominent and severe, it can present with erosions or ulceration of the eyes, lips, mouth, oesophagus, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, liver, anus, genital area or urethra.

Differential diagnoses

Table 1. Differential diagnoses for SJS/TEN.

| Differential diagnosis | Aetiology | Signs/Symptoms | Investigations |

|

Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS).8,15 |

2-6 weeks from the beginning of drug therapy to onset of rash Most commonly due to phenytoin, carbamazepine, allopurinol and sulphonamides |

Fever Morbilliform eruption Erythroderma and exfoliative dermatitis Lymphadenopathy Mucosal involvement affects 25% |

Skin biopsy: dense infiltration of inflammatory cells FBC: eosinophilia LFTs: deranged

|

|

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome/toxic shock syndrome.16 |

Caused by the release of two exotoxins from Staphylococcus aureus Mostly occurs in children <5 years and particularly neonates |

Fever, irritability Red, blistering skin resembling a burn, often in the skin flexures Nikolsky sign positive |

Skin biopsy: intraepidermal cleavage at the granular layer Bacterial culture from skin, blood, urine or umbilical cord sample

|

|

Morbilliform/maculopapular drug reaction.17 |

Most common form of drug reaction Antibiotics are the most common causative group

|

Maculopapular rash on the trunk, spreading to the limbs and neck Bilateral and symmetrical distribution Mucous membranes, hair and nails are not affected |

Diagnosis is based on a strong clinical suspicion. Typical exanthematous rash Recently introduced medication |

|

Erythema mutiforme major (with mucosal involvement).18 |

Usually triggered by infections, most commonly herpes simplex virus (HSV) |

Typical target lesions Mucous membrane involvement Acute, self-limiting, usually resolving without complications |

Clinical diagnosis Skin biopsy to exclude other conditions |

|

Bullous pemphigoid.19 |

Autoimmune sub-epidermal blistering disease Often seen in people >80 years with neurological disease i.e. stroke |

Non-specific rash for several weeks before blisters appear Severe itch, large, tense bullae which rupture to form crusted erosions Oral and genital lesions uncommon |

Skin biopsy: direct immunofluorescence staining highlights antibodies along the basement membrane Indirect immunofluorescence test for antibodies

|

|

Pemphigus vulgaris & Paraneoplastic pemphigus.20 |

Autoimmune blistering disease Paraneoplastic in patients with a malignancy |

Painful blisters and erosions on the skin and mucous membranes Skin lesions are thin-walled flaccid blisters |

Skin biopsy: direct immunofluorescence reveal IgG antibodies or complement Indirect immunofluorescence to detect circulating antibodies in the blood |

|

Graft-versus-host disease.3 |

Usually follows bone marrow transplantation, although solid organ and blood transfusions have also been reported |

Burning, erythematous rash and blistering |

Clinical diagnosis Skin biopsy to exclude other differential diagnoses

|

|

Chemical or thermal burns.7 |

Thermal burn caused by an external heat source |

Superficial (1st degree burns) to full thickness (3rd degree) involving all layers of the skin |

Skin biopsy if there is not a good history

|

Investigations

Characteristic clinical presentation and a skin biopsy is sufficient to diagnose the condition. A biopsy taken at the transition point of blistering can assess the level of desquamation.8

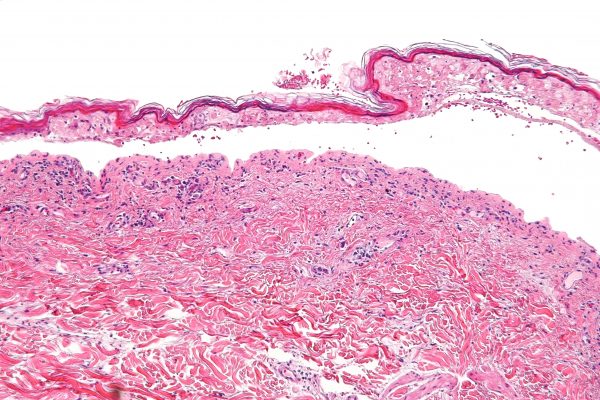

Histopathology reveals keratinocyte necrosis, full-thickness epidermal/epithelial necrosis (figure 5), and minimal inflammation. Direct immunofluorescence may be performed to exclude autoimmune blistering disease.6

Laboratory investigations

Blood tests do not help make the diagnosis but are essential to identify complications and assess prognostic factors.1

Table 2. Laboratory investigations for SJS/TEN.1,8

| Investigation | Description |

|

Hb |

Anaemia occurs in virtually all cases |

|

WCC |

Leucopenia, especially lymphopenia is very common (90%). May be elevated if wound infection or sepsis is present. Neutropenia is a bad prognostic sign |

|

Eosinophils |

If eosinophilia is present, consider a hypersensitivity syndrome (e.g. DRESS) |

|

LFTs |

Mildly deranged LFTs are common (30%), and ~10% develop hepatitis |

|

U&Es |

Important to assess hypovolaemia and exclude renal failure |

|

Glucose |

Necessary to rule out hypoglycaemia and other comorbidities e.g diabetes |

|

Magnesium |

Hypomagnesaemia is often seen in patients with thermal injury skin loss |

|

Phosphate |

Elevated or decreased levels suggest muscle damage, which may cause joint pain, weakness, seizures or renal injury |

|

Urine dip |

Mild proteinuria occurs in 50% |

|

Blood culture |

Important to rule out infection with Staphylococcus or Streptococcus specious causing toxic shock syndrome or scalded skin syndrome |

|

Arterial blood gas |

To assess for respiratory compromise (hypoxaemia/acidosis) |

|

Chest X-ray |

Rule out underlying LRTI/pneumonia |

Assessment of the percentage of body surface area (TBSA) involved is important in classifying SJS/TEN.8

Approximately one hand (palm and fingers) of the patient is equivalent of 1% TBSA.8

SCORTEN scoring system

The SCORTEN scoring system provides an accurate prediction of mortality in patients with SJS/TEN. This should be calculated within the first 24 hours of hospitalisation, and continued for the first 5 days of admission.21

Table 3. An overview of the SCORTEN scoring system for SJS/TEN.21

|

Prognostic factors |

Points |

SCORTEN score |

Mortality % |

|

Age >40 years |

1 |

0-1 |

3 |

|

Heart rate >120 bpm |

1 |

2 |

12 |

|

Cancer or haematological malignancy |

1 |

3 |

35 |

|

Initial TBSA involved >10% |

1 |

4 |

58 |

|

Serum urea level >10mmol/L |

1 |

≧ 5 |

90 |

|

Serum bicarbonate level <20mmol/L |

1 |

|

|

|

Serum glucose level >14mmol/L |

1 |

|

|

In 2019, a new prediction model was proposed, the ABCD-10.1

Management

SJS/TEN is similar to second-degree burns in terms of physical effects, and are therefore treated in the same way.4,8 This entails optimal daily wound care, oral care and nutrition, fluid balance, pain management and eye care.1

Immediate care

Withdraw the causative agent immediately. It is often a new medication prescribed for the patient within the last 2-4 weeks prior to the onset of the rash.8

Examine the patient using the ABCDE approach.8

Determine whether the patient is in respiratory distress. Arterial blood gases and oxygen saturation will help determine clinical respiratory status. Intubation and mechanical ventilation may be necessary to maintain the airway.14

Establish peripheral venous access.21

An immediate assessment of total body surface area (TBSA).8

Calculate SCORTEN within the first 24 hours.11

Care setting

A multidisciplinary team coordinated by a dermatologist or plastic surgeon specialised in skin failure helps improve outcomes and reduce adverse complications.4

Patients with greater than 10% TBSA loss or a SCORTEN score >3 should be admitted without delay to a burn centre or intensive care unit with facilities to manage extensive skin loss would care. This improves survival and reduces the risk of infection.1,4,11

Strict barrier nursing in a side-room must be employed to reduce nosocomial infections. Use of a pressure-relieving mattress with temperature control is imperative.11

Skin care

Skin should be examined daily for the extent of detachment and infection. Regular cleansing using gently warmed sterile water, saline or an antimicrobial (e.g. chlorhexidine) and a topical antimicrobial agent to sloughy areas.1,11

Non-adherent dressings to denuded dermis can reduce pain. The detached, lesional epidermis may be left in situ to act as a biological dressing.1,11

Apply a greasy emollient such as 50% white soft paraffin with 50% liquid paraffin, over the whole epidermis, including denuded areas. Once the skin has regenerated (after about 2-3 weeks), emollients are useful to keep skin supple and to aid healing.8,11

Eye care

Daily assessment by an ophthalmologist is necessary during the acute illness in a bid to preserve vision and reduce complications.1,22

Frequent use of eye drops/ointments (lubricants, antiseptics, antibiotic, corticosteroid) is key. In the unconscious patient, prevention of corneal exposure is essential.1,11

Fluid balance

Encourage patients who can take fluids orally to do so, otherwise commence intravenous fluid replacement. Whenever possible, place venous lines through non-lesional skin and change cannulas every 48 hours.11

Monitor fluid balance carefully and catheterise if necessary.11

Oral hygiene and nutritional support

A daily oral review is necessary during the acute illness.11

Use soothing mouthwash (e.g. lidocaine), anti-inflammatory and antiseptic oral rinse/spray for oral hygiene in people with oral mucous membrane involvement. Cleanse the mouth daily with warm saline mouthwashes.4

Give nutritional support to patients with stomatitis who are unable to tolerate normal eating either orally or via an enteral feeding tube. Due to increased catabolism, these patients require high caloric nutrition supplements.4

Analgesia

Use paracetamol with morphine sulphate. Do not use non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs), unless other analgesics do not work. NSAIDs and paracetamol are known causative agents. Patients will undoubtedly require more pain medicine during patient handling, re-positioning and dressing changes.4,11

Urogenital involvement

Apply white soft paraffin ointment to the urogenital skin and mucosa every four hours throughout the acute illness.11 If ulcerated, prevent vaginal adhesions using intravaginal steroid ointment and soft vaginal dilators.1

Catheterise if genital involvement and culture urine for bacterial infection.1

Airway involvement

Respiratory symptoms and hypoxaemia on admission should prompt early discussion with an intensivist and rapid transfer to ICU where intubation and mechanical ventilation should be undertaken.11 Consider aerosols, bronchial aspiration and chest physiotherapy.1

General care

Prophylactic anticoagulation should be prescribed along with a proton-pump inhibitor to prevent stress-related gastritis and intestinal ulceration.1

Regular assessment for staphylococcal or gram-negative infection. The appropriate antibiotics should only be given if there are clinical signs of infection; prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended and may even increase the risk of sepsis.1,11

Psychiatric support for extreme anxiety and emotional lability.1

Physiotherapy and occupational therapy: patients can develop limitations in mobility, decreased strength and joint contractures.11

Novel therapies

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG): there are no clear indications regarding the administration of IVIG and no definitive randomised controlled trials to guide treatment. Some clinicians give IVIG to patients with a rapidly progressing rash involving >6% TBSA. Others give this when 20% TBSA is affected.4

Ciclosporin: there have been sporadic case reports of successful treatment of SJS/TEN with ciclosporin. In a retrospective review of 71 patients with SJS/TEN, ciclosporin was associated with fewer deaths than expected while IVIG was associated with excess mortality.23

Discharge and follow-up

Patients should receive written information about the drug(s) to avoid and should avoid the use of the medicine that initiated the illness. Encourage the patient to wear a MedicAlert bracelet.11

Drug allergy should be documented in patients notes, discharge letters and medical records. All doctors involved in the patient’s care should be informed including drug name, route of administration, time interval between first dose and event, and nature of severity.11,8

Report the episode to the national pharmacovigilance authorities.11

Organise outpatient follow-up as required (e.g. gynaecology, ophthalmology).11

Secondary prevention

Patients should be alert to any mucosal erosions, ulcerations or rash development. They should seek medical advice as soon as possible because SJS/TEN has been known to recur several times in the same individual.11

Patients should avoid sunlight exposure and sunburn for at least 1 year to promote healing of skin, especially the areas that were affected by the rash, blisters and sloughing.8 They should use an emollient to aid skin healing.8

Because they may have a genetic predisposition, these patients should never self-medicate with antibiotics or over the counter drugs without a doctor’s approval.8

Complications

The acute phase of SJS/TEN typically lasts between 8-12 days.1

Repithelialsiation of denuded areas takes several weeks and is accompanied by peeling of the less severely affected skin.1

SJS/TEN can be fatal due to complications in the acute phase. The mortality rate is up to 10% for SJS and at least 30% for TEN.1

Patients <50 years of age, with a low TBSA percentage, who receive care at an acute burn centre, do not develop sepsis or require antibiotics confer the best prognosis.8

Table 4. The acute complications of SJS/TEN.13

|

Acute complication |

Description |

|

Dehydration |

Stomatitis, vomiting and fluid loss through denuded skin surface |

|

Infection |

Loss of skin surface exposes the dermis and increases the risk of infection |

|

Hypothermia |

With the loss of 15-20% or more of TBSA through skin sloughing, patients lose their thermoregulatory capability |

|

Ocular complications |

Pseudomembranous conjunctivitis, tear duct loss, corneal ulcerations, anterior uveitis |

|

Acute liver injury |

Fatty liver, hepatocyte apoptosis, and necrosis |

|

Acute renal failure |

Renal insults occur, leading to acute tubular necrosis and renal failure |

|

Gastrointestinal complications |

Gastrointestinal ulceration, perforation, and intussusception |

|

Coagulopathy |

Thromboembolism and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy |

|

Other |

Shock and multi-organ failure |

Table 5. The chronic complications of SJS/TEN.1,6,13

|

Chronic complication |

Description |

|

Abnormal skin pigmentation |

A patchwork of increased and decreased pigmentation |

|

Skin scarring |

Especially at sites of pressure or infection |

|

Nail plate loss |

Permanent scarring and failure to regrow |

|

Acute compartment syndrome |

Extremely rare but may occur in the extremities or torso |

|

Vaginal synechiae |

Undiagnosed, this could impair sexual intercourse or normal vaginal delivery |

|

Pulmonary complications |

Bronchitis, bronchiolitis obliterans, bronchiectasis |

Key points

- Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) may be associated with a preceding history of medication use, most commonly, antibiotics, anticonvulsants and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.8

- Patients may present with Nikolsky’s sign, where the epidermal layer easily sloughs off when pressure is applied to the blistered or erythematous area.8

- Diagnosis is made by clinical presentation and confirmed with a skin biopsy.8

- The offending medicine should be stopped immediately. Management is then largely supportive.8

- Patients do best if they are sent to a burn centre/intensive care unit as soon as the diagnosis is suspected or made.8

- The majority of SJS patients recover (mortality 2-10%). SJS can recur either with the same medicine or with another medicine.8

- TEN has a higher mortality of approximately 30%.8

- In the long term, patients should ensure they are not re-exposed to the trigger medicine and be careful of self-medicating. They should avoid sunlight and moisturise their skin during the healing phase.8

Reviewer

Dr Katherine Finucaine

Associate Specialist in Dermatology, North Bristol NHS Trust

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

Text references

- DermNet NZ. Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. Published in 2003. Available from: [LINK]

- Tidy C. Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. Published in 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- Mockenhaupt M. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: clinical patterns, diagnostic considerations, etiology, and therapeutic management. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2014 Mar;33(1):10-6

- Mockenhaupt M; The current understanding of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2011 Nov7(6):803-13

- Mittmann N, Knowles SR, Koo M, et al; Incidence of toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson Syndrome in an HIV cohort: an observational, retrospective case series study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012 Feb 113(1):49-54. doi: 10.2165/11593240-000000000-00000.

- Paul C, Wolkenstein PC, Adle H, et al. Apoptosis as a mechanism of keratinocyte death in toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol. 1996 Apr;134(4):710-4.

- Dodiuk-Gad RP, Chung WH, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015 Dec;16(6):475-93.

- Roujeau JC, Kelly JP, Naldi L, et al. Medication use and the risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis. N Engl J Med. 1995 Dec 14;333(24):1600-7

- Roujeau JC, Stern RS. Severe adverse cutaneous reactions to drugs. N Engl J Med. 1994 Nov 10;331(19):1272-85.

- BMJ Best Practice. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Published in 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Vern-Gross TZ, Kowal-Vern A. Erythema multiforme, Stevens Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis syndrome in patients undergoing radiation therapy: a literature review. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014 Oct;37(5):506-13.

- Creamer D, Walsh SA et al. UK guidelines for the management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis 2016. Br J Dermatol 2016; 174: 1194-1227 & J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2016; 69: e119-e153

- Chang CC, Too CL, Murad S, et al. Association of HLA-B*1502 allele with carbamazepine-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome in the multi-ethnic Malaysian population. Int J Dermatol. 2011 Feb;50(2):221-4.

- Harr T, French LE; Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Chem Immunol Allergy. 201297:149-66. Epub 2012 May 3.

- de Prost N, Mekontso-Dessap A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Acute respiratory failure in patients with toxic epidermal necrolysis: clinical features and factors associated with mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2014 Jan;42(1):118-28.

- Prof. Redemaker M. Drug hypersensitivity syndrome. Published in 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- Oakley A. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Published in 2002. Available from: [LINK]

- Dyall-Smith D. Morbilliform drug reaction. Published in 2009. Available from: [LINK]

- Oakley A. Erythema multiforme. Published in 1997. Available from: [LINK]

- Oakley A. Bullous pemphigoid. Published in 1997. Available from: [LINK]

- Ngan V. Pemphigus Published in 2003. Available from: [LINK]

- Sekula P, Liss Y, Davidovici B, et al. Evaluation of SCORTEN on a cohort of patients with Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis included in the RegiSCAR study. J Burn Care Res. 2011 Mar-Apr;32(2):237-45

- Gregory DG. New grading system and treatment guidelines for the acute ocular manifestations of Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2016 Aug;123(8):1653-8.

- Kirchhof MG, Miliszewski MA, Sikora S, et al. Retrospective review of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis treatment comparing intravenous immunoglobulin with cyclosporine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Nov;71(5):941-7.

Image references

- Figure 1. Jay2Base. Early-stage blisters on the back TENS patient. License: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Figure 2. AfroBrazilian. Necrolysis Epidermalis toxica. License: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Figure 3. Jay2Base. TENS patient on day 10. License: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Figure 4. James Heilman, MD. Mucosal desquamation in a person with Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. License: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Figure 5. Nephron. Intermediate magnification micrograph of confluent epidermal necrosis. Skin biopsy. H&E stain. License: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]