- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Head injury is defined as any trauma to the head regardless of mechanism or presence of neurological symptoms.1

This guide provides an overview of the recognition and immediate management of a traumatic head injury using an ABCDE approach.

The ABCDE approach can be used to perform a systematic assessment of a critically unwell patient. It involves working through the following steps:

- Airway

- Breathing

- Circulation

- Disability

- Exposure

Each stage of the ABCDE approach involves clinical assessment, investigations and interventions. Problems are addressed as they are identified and the patient is re-assessed regularly to monitor their response to treatment.

This guide has been created to assist students in preparing for emergency simulation sessions as part of their training, it is not intended to be relied upon for patient care.

Basic principles & pathophysiology

The severity of head injuries can vary from minor head injuries to life-threatening traumatic brain injury (TBI) and/or intracranial haemorrhage.

Traumatic head injuries are a common presentation, with 1.4 million patients attending emergency departments in the United Kingdom every year.1

Although the incidence of death from head injuries overall is low (0.2%), the consequences of missing major pathology can be catastrophic. Head injuries are the most common cause of death and disability in those under the age of 40 in the UK.1

The Monro-Kellie doctrine

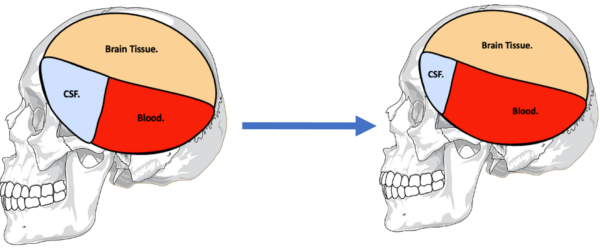

The Monro-Kellie hypothesis describes the relationship between the contents of the skull and intracranial pressure (ICP).

The skull is a closed rigid box with a fixed capacity (after the sutures have closed).

Within the skull there are three main substances:

- Brain tissue,

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

- Blood

If the volume of one of these substances increases, to maintain a constant ICP, the volume of one of the others must decrease. Initially, this can be achieved through a process referred to as compliance.

An increase in the amount of blood in the skull leads to a compensatory decrease in the amount of CSF and normal ICP is maintained (Figure 1).

Once the compensatory compliance mechanism is overwhelmed, small increases in the volume of any one of the three substances will lead to dramatic increases in ICP (Figure 2). In head injuries, the volume of brain tissue or blood within the skull can increase secondary to swelling (i.e. oedema) or haemorrhage. If left untreated, rising ICP leads to a progressive reduction in cerebral perfusion, herniation of the brainstem and ultimately death.

Clinical features of raised ICP

Clinical features of raised ICP can include:

- Headache

- Nausea and vomiting

- Restlessness, agitation or drowsiness

- Slow slurred speech

- Papilloedema

- Ipsilateral sluggish dilated pupil which then becomes fixed (“blown pupil”)

- Cranial nerve palsy (e.g. CN III palsy with ‘down and out’ pupil)

- Seizures

- Reduced GCS

- Abnormal respiratory pattern

- Abnormal posturing, initially decorticate and then decerebrate

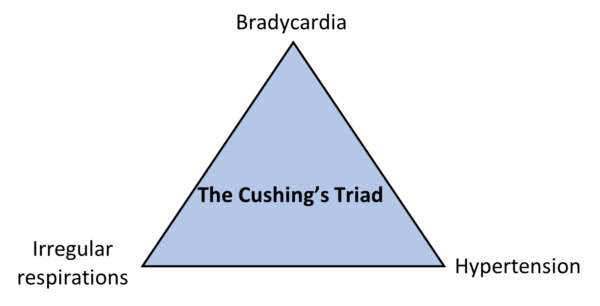

Cushing’s reflex is a physiological response to raised ICP which attempts to improve perfusion. It leads to a triad of hypertension, bradycardia, and an irregular breathing pattern (Figure 3).

Cerebral Perfusion Pressure (CPP)

Cerebral perfusion pressure is the pressure driving blood through the brain tissue, allowing the delivery of oxygen and nutrients. CPP can be calculated using the equation below:

CPP = Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP) – ICP

A rise in ICP will reduce CPP. If CPP drops too low for a significant amount of time, ischaemia occurs.

Herniation

Herniation can be defined as the movement of brain structures from one cranial compartment to another. Herniation of different brain structures leads to different clinical features.

Herniation of the cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum leads to compression of the brainstem and respiratory arrest. This is often referred to as ‘coning’.

Herniation of the uncus of the temporal lobe through the tentorial notch often leads to compression of cranial nerve three (oculomotor nerve) leading to the classical “blown pupil” that is often assessed for in TBI patients.

Primary and secondary brain injury

Primary brain injury is the initial injury caused to brain tissue from the forces of the traumatic event itself. This may be focal (e.g. skull fractures, blood vessel injury and haematoma formation) or diffuse (e.g. contusion).

Secondary brain injury is indirect damage to brain tissue that that occurs after the primary insult, worsening the original injury. Common causes include inadequate perfusion of the brain causing cerebral hypoxia, acidosis, hypoglycaemia and cerebral oedema leading to raised ICP.

Primary brain injury has already occurred in patients who present with a head injury. A key part of head injury management is to minimise secondary brain injury.

Table 1. Factors that may contribute to secondary brain injury, and the interventions to try to limit them.

|

Contributing factors |

Interventions |

|

Hypoxia and hypercapnia |

Oxygen to maintain saturations of 94-98% Intubation in patients unable to protect their airway or with poor respiratory effort |

|

Hypovolaemia and hypotension |

Resuscitate with intravenous fluids or blood products Vasopressors |

|

Cerebral oedema and raised ICP |

Avoid tight C-spine collars Position the patient at 30° to aid venous drainage Mannitol or hypertonic saline to reduce ICP Intubation and hyperventilation strategies |

|

Expanding haematoma |

Reverse clotting abnormalities Consider the use of tranexamic acid if < 3 hours since injury Neurosurgical intervention |

|

Hypoglycaemia or hyperglycaemia |

Maintain blood glucose within normal range with insulin or dextrose as required |

|

Increased metabolic demand (e.g. hyperthermia or seizures) |

Maintain normothermia Anti-convulsant medications if seizure activity Neuroprotective anaesthesia |

Clinical features

History

Patients who have sustained a head injury may not be able to provide an accurate history as a result of the injury itself (e.g. due to reduced consciousness).

Where possible, obtain a collateral history. If the patient was bought in by ambulance, try to gather a detailed history and description of the scene from the paramedics.

In the context of acute severe head trauma, taking a history should not delay performing an urgent ABCDE assessment to identify and address serious pathology.

A more detailed history can be obtained once the patient is stable.

Typical symptoms of a traumatic head injury include:

- Pain localised to the area of trauma

- Headache

- Drowsiness or loss of consciousness

- Nausea and vomiting

- Confusion or irritability

- Changes in hearing (ringing in ears, hearing loss) or vision (double vision, blurring, visual field loss)

- Memory loss (amnesia) or concentration difficulties

- Weakness or sensory changes such as numbness or paraesthesia

- Difficulties with speech (e.g. slurring)

- Dizziness or issues with balance

Other important areas to cover in the history include:

- A detailed account of the event. This includes when the head injury occurred, how it occurred, and which part of the head took the impact. Find out if the patient was intoxicated or taking any illicit drugs at the time.

- Establishing if the patient has any neurological symptoms. This includes seizure activity, weakness, sensory or visual changes.

- Whether there was any loss of consciousness after the injury and establishing if the patient has any amnesia.

- Whether the patient has any symptoms that may be due to raised ICP (covered previously).

- Drug history: establish whether the patient is taking any anticoagulants and if they have any drug allergies.

- A focused past medical history: establish if the patient has a bleeding disorder; has previously had brain surgery or sustained a significant head injury.

- A focused social history: establish the patient’s baseline functioning and what their home situation is. Take a brief alcohol and drug history.

- Whether the patient has sustained any other injures. Specifically, ask about pain in the cervical spine. NICE have guidelines on when c-spine immobilisation should be performed.3

If the head injury was due to a fall, then this should be explored further, and the cause of the fall should be sought. See our article on falls assessment and management.

Clinical signs

Typical clinical signs associated with a traumatic head injury include:

- Lacerations, abrasions, bruising and swelling over the area of the head that has sustained trauma

- Decreased consciousness (GCS) or drowsiness

- Confusion

- Irritability

- Focal neurological signs such as weakness or sensory loss

- Abnormal findings on cranial nerve examination such as visual field loss; abnormally shaped or sized pupils; and speech difficulties

- Impaired coordination on examination

- Signs of basal skull fracture: this includes CSF tracking from the nose or ears and bruising around the eyes or behind the ears

- Impairments in memory

Tips before you begin

General tips for applying an ABCDE approach in an emergency setting include:

- Treat all problems as you discover them.

- Re-assess regularly and after every intervention to monitor a patient’s response to treatment.

- Make use of the team around you by delegating tasks where appropriate.

- All critically unwell patients should have continuous monitoring equipment attached for accurate observations.

- Clearly communicate how often would you like the patient’s observations relayed to you by other staff members.

- If you require senior input, call for help early using an appropriate SBARR handover

- Review results as they become available (e.g. laboratory investigations).

- Make use of your local guidelines and algorithms in managing specific scenarios (e.g. acute asthma).

- Any medications or fluids will need to be prescribed at the time (in some cases you may be able to delegate this to another member of staff).

- Your assessment and management should be documented clearly in the notes, however, this should not delay initial clinical assessment, investigations and interventions.

Initial steps

Acute scenarios typically begin with a brief handover from a member of the nursing staff including the patient’s name, age, background and the reason the review has been requested.

You may be asked to review a patient with a traumatic head injury in the emergency department or following a fall on the wards.

Introduction

Introduce yourself to whoever has requested a review of the patient and listen carefully to their handover.

Interaction

Introduce yourself to the patient including your name and role.

Ask how the patient is feeling as this may provide some useful information about their current symptoms.

In the context of a head injury, this may not be possible due to impaired consciousness.

Preparation

Make sure the patient’s notes, observation chart and prescription chart are easily accessible.

Ask for another clinical member of staff to assist you if possible.

If the patient is unconscious or unresponsive, start the basic life support (BLS) algorithm as per resuscitation guidelines

Airway

In patients with head injuries, the airway may be compromised due to a number of factors such as:

- Blood or swelling in the airway

- Vomit or secretions

- Reduced consciousness (from the head injury itself or other factors e.g. intoxication)

Clinical assessment

Can the patient talk?

Yes: if the patient can talk, their airway is patent and you can move on to the assessment of breathing.

No:

- Look for signs of airway compromise: these include cyanosis, see-saw breathing, use of accessory muscles, diminished breath sounds and added sounds.

- Open the mouth and inspect: look for anything obstructing the airway such as secretions or a foreign object.

Interventions

Regardless of the underlying cause of airway obstruction, seek immediate expert support from an anaesthetist and the emergency medical team (often referred to as the ‘crash team’). In the meantime, you can perform some basic airway manoeuvres to help maintain the airway whilst awaiting senior input.

Head-tilt chin-lift manoeuvre

The head tilt-chin lift manoeuvre should be avoided if there is any concern of a spinal injury.

Jaw thrust

If the patient is suspected to have suffered significant trauma with potential spinal involvement, perform a jaw-thrust rather than a head-tilt chin-lift manoeuvre:

1. Identify the angle of the mandible.

2. With your index and other fingers placed behind the angle of the mandible, apply steady upwards and forward pressure to lift the mandible.

3. Using your thumbs, slightly open the mouth by downward displacement of the chin.

Oropharyngeal airway (Guedel)

Airway adjuncts are often helpful and, in some cases, essential to maintain a patient’s airway. They should be used in conjunction with the manoeuvres mentioned above as the position of the head and neck need to be maintained to keep the airway aligned.

An oropharyngeal airway is a curved plastic tube with a flange on one end that sits between the tongue and hard palate to relieve soft palate obstruction. It should only be inserted in unconscious patients as it is otherwise poorly tolerated and may induce gagging and aspiration.

To insert an oropharyngeal airway:

1. Open the patient’s mouth to ensure there is no foreign material that may be pushed into the larynx. If foreign material is present, attempt removal using suction.

2. Insert the oropharyngeal airway in the upside-down position until you reach the junction of the hard and soft palate, at which point you should rotate it 180°. The reason for inserting the airway upside down initially is to reduce the risk of pushing the tongue backwards and worsening airway obstruction.

3. Advance the airway until it lies within the pharynx.

4. Maintain head-tilt chin-lift or jaw thrust and assess the patency of the patient’s airway by looking, listening and feeling for signs of breathing.

Nasopharyngeal airway (NPA)

A nasopharyngeal airway is a soft plastic tube with a bevel at one end and a flange at the other. NPAs are typically better tolerated in patients who are partly or fully conscious compared to oropharyngeal airways.

The use of nasopharyngeal airways in head injury is controversial. They are generally better tolerated than oropharyngeal airways in patients who are partially or fully conscious and may be the only option in severe facial fractures or trismus. However, the general consensus is that they should not be used if there is any concern that the patient may have a basal skull fracture.

Basal skull fracture

Signs suggestive of a basal skull fracture include:

- CSF (clear fluid) leaking from nose or ear

- Raccoon eyes: bruising around the eyes

- Battle sign: bruising behind the ear over the mastoid process

- Haemotympanum: blood noted behind the tympanic membrane on otoscopy

CPR

If the patient loses consciousness and there are no signs of life on assessment, put out a crash call and commence CPR.

Re-assessment

Make sure to re-assess the patient following any intervention.

Breathing

Ventilation must be sufficient to prevent secondary brain injury from cerebral hypoxia and hypercapnia. Abnormalities in the patient’s respiratory pattern may indicate raised ICP.

Clinical assessment

Observations

Review the patient’s respiratory rate:

- A normal respiratory rate is between 12-20 breaths per minute.

- Bradypnoea may be secondary to raised ICP and is seen as part of the Cushing’s reflex. Consider other causes of a reduced RR such as opioid toxicity.

- Tachypnoea may be due to pain or agitation, acidosis or due to the presence of respiratory pathology.

Review the patient’s oxygen saturations (SpO2):

- A normal SpO2 range is 94-98% in healthy individuals and 88-92% in patients with COPD who are at high-risk of CO2 retention.

- Hypoxaemia may occur due to associated injuries or respiratory issues and can contribute to secondary brain injury.

See our guide to performing observations/vital signs for more details.

Inspection

Look for signs of cyanosis, respiratory distress, use of accessory muscles, and abnormal breathing patterns.

Deep irregular breathing can be caused by raised ICP.

Assess for equal chest expansion with respiration and for any obvious chest wall trauma.

Palpation

Palpate the position of the patient’s trachea and assess chest expansion.

Assess for any chest wall tenderness that may signify chest wall trauma.

Auscultation

Auscultate both lungs:

- Assess for good air entry throughout the chest

- Assess for any added sounds such as crackles and wheeze

Investigations and procedures

Arterial blood gas

Take an ABG if indicated (e.g. low SpO2) to quantify the degree of hypoxia.

Chest X-ray

A chest x-ray may be needed if examination suggests other respiratory pathology.

Intubation and ventilation

Indications for intubation and ventilation are:

- pO2 < 13kPa on supplemental oxygen

- pCO2 > 6kPa

- Spontaneous hyperventilation causing pCO2 < 3.5kPa

Interventions

Oxygen

Administer oxygen to all critically unwell patients during your initial assessment. This typically involves the use of a non-rebreathe mask with an oxygen flow rate of 15L. You can then trial titrating oxygen levels downwards after your initial assessment.4

If the patient has COPD and a history of CO2 retention you should switch to a venturi mask as soon as possible and titrate oxygen appropriately.

Assisted ventilation

If your patient is unconscious and their respiratory rate is inadequate (too slow or irregular with big pauses), you can provide assisted ventilation through a bag-valve-mask (BVM): ventilate at a rate of 12-15 breaths per minute (roughly one every 4 seconds).

Other interventions

Other interventions may be appropriate depending on examination findings (e.g., aspiration of tension pneumothorax).

Re-assessment

Make sure to re-assess the patient following any intervention.

Circulation

In patients with TBI, it is important to maintain an adequate mean arterial pressure to ensure adequate cerebral perfusion.

Mortality is significantly increased in patients with TBI who have periods in which their systolic blood pressure is less than 90mmHg.

Aim for a MAP > 90mmHg or systolic BP > 110mmHg. A lower BP may sometimes be permitted in patients with multiple injuries or major haemorrhage.

Clinical assessment

Observations

Review the patient’s heart rate:

- Causes of tachycardia (HR>99) in the context of head injury include hypovolaemia, arrhythmia, pain or drugs.

- Causes of bradycardia (HR<60) in the context of head injury include Cushing’s reflex and opioid use.

Review the patient’s blood pressure:

- A normal blood pressure (BP) range is between 90/60mmHg and 140/90mmHg but you should review previous readings to gauge the patient’s usual baseline BP.

- Causes of hypertension in the context of acute head injury include pain and Cushing’s reflex.

- Causes of hypotension in the context of acute head injury include haemorrhage from other injuries, and drugs (e.g. opiates).

See our guide to performing observations/vital signs for more details.

General inspection

Inspect the patient from the end of the bed whilst at rest, looking for clinical signs suggestive of underlying pathology:

- Pallor or mottled skin: commonly associated with hypovolaemic shock (e.g. haemorrhage).

Palpation

Place the dorsal aspect of your hand onto the patient’s to assess temperature:

- In healthy individuals, the hands should be symmetrically warm, indicating adequate perfusion.

- Cool hands indicate poor peripheral perfusion (e.g. hypovolaemic shock).

Measure capillary refill time (CRT):

- In healthy individuals, the initial pallor of the area you compressed should return to its normal colour in less than two seconds.

- A CRT that is greater than two seconds suggests poor peripheral perfusion (e.g. hypovolaemia) and the need to assess central capillary refill time.

Pulses and blood pressure

Assess the patient’s radial and brachial pulse to assess rate, rhythm, volume and character:

- An irregular pulse is associated with arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation.

- A thready pulse is associated with intravascular hypovolaemia (e.g. haemorrhage).

Auscultation

Auscultate the patient’s precordium to assess heart sounds, listening for evidence of murmurs.

Investigations and procedures

Intravenous cannulation

Insert at least one wide-bore intravenous cannula (14G or 16G) and take blood tests as discussed below.

See our intravenous cannulation guide for more details.

Blood tests

Request the following blood tests:

- FBC

- U&Es

- LFTs

- Coagulation screen

- Group & save (+/- crossmatch)

- Toxicology screen (if you suspect drug overdose)

- Lactate (to assess for evidence of inadequate end-organ perfusion)

See our blood culture, blood bottle and investigation panel guides for more details.

ECG

Perform an ECG if to identify any abnormal rhythms which may be contributing to poor perfusion.

Attach 3-lead continuous ECG monitoring if available.

See our guides to recording and interpreting an ECG for more details.

Interventions

Hypovolaemia

Hypovolaemic patients require fluid resuscitation (the below guidelines are for adults):

- Administer a 500ml bolus Hartmann’s solution or 0.9% sodium chloride (warmed if available) over less than 15 mins.

- Administer 250ml boluses in patients at increased risk of fluid overload (e.g. heart failure).

After each fluid bolus, reassess for clinical evidence of fluid overload (e.g. auscultation of the lungs, assessment of JVP).

Repeat administration of fluid boluses up to four times (e.g. 2000ml or 1000ml in patients at increased risk of fluid overload), reassessing the patient each time.

Seek senior input if the patient has a negative response (e.g. increased chest crackles) or if the patient isn’t responding adequately to repeated boluses (e.g. persistent hypotension).

See our fluid prescribing guide for more details on resuscitation fluids.

Hypertension

Hypertension in traumatic head injury is generally left alone unless it is dangerously elevated, as it is often a homeostatic response to ensure there is adequate cerebral perfusion.

Coagulation abnormalities

If a patient is found to have coagulation abnormalities in the context of acute head injury (e.g. raised PT or INR) they will likely require treatment to reduce their risk of further bleeding.

Correction of coagulation abnormalities is typically lead by the on-call haematologist.

CPR

If the patient loses consciousness and there are no signs of life on assessment, put out a crash call and commence CPR.

Re-assessment

Make sure to re-assess the patient following any intervention.

Disability

Clinical assessment

Consciousness

Assess the patient’s level of consciousness by using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS).

A summary of the Glasgow coma scale is shown below. For a more detailed explanation, see the Geeky Medics guide to the Glasgow Coma Scale.

Table 2. An overview of the Glasgow Coma Scale.

| Behaviour/domain | Response | Score |

|

Eye-opening response |

Eyes opening spontaneously |

4 |

|

Eyes opening to sound |

3 |

|

|

Eyes open to pain |

2 |

|

|

No eye opening |

1 |

|

|

Verbal response |

Orientated to time, place and person |

5 |

|

Confused |

4 |

|

|

Inappropriate sounds |

3 |

|

|

Incomprehensible sounds (e.g. groaning) |

2 |

|

|

No response |

1 |

|

|

Motor response |

Obeys commands for movement |

6 |

|

Moves towards pain/localises to pain |

5 |

|

|

Withdraws away from pain |

4 |

|

|

Abnormal flexion/decorticate posturing |

3 |

|

|

Abnormal extension/decerebrate posturing |

2 |

|

|

No motor response |

1 |

Head injuries are classified as mild, moderate, or severe based on the patient’s GCS following the injury:

- Mild head injury: GCS of 14/15

- Moderate head injury: GCS 9-13

- Severe head injury: GCS <8

Assess if the patient is orientated to person, place and time.

Pupils

Assess the patient’s pupils:

- Assess the size and shape of the patient’s pupils. A normal pupil diameter ranges from two to five millimetres.

- Assess the pupils for both direct and consensual response to light using a pen torch.

- An oval-shaped pupil, sluggish reaction to light, “blown pupil” or deviated pupil suggests raised ICP or herniation.

- Bilaterally small or “pinpoint” pupils may be due to opioid toxicity.

Neurological examination

Perform a neurological examination in patients who are able to follow commands, assessing:

- Cranial nerves

- Power in each limb (see our upper limb and lower limb neurological examination guides)

- Sensation in each limb

- Cerebellar function

A new neurological deficit suggests intracranial injury.

Investigations

Blood glucose

Measure the patient’s capillary blood glucose level to screen for causes of a reduced level of consciousness (e.g. hypoglycaemia or hyperglycaemia).

A blood glucose level may already be available from earlier investigations (e.g. ABG, venepuncture).

The normal reference range for fasting plasma glucose is 4.0 – 5.8 mmol/l.

Hypoglycaemia is defined as a plasma glucose of less than 3.0 mmol/l. In hospitalised patients, a blood glucose ≤4.0 mmol/L should be treated if the patient is symptomatic.

See our blood glucose measurement and hypoglycaemia guides for more details.

Imaging

In the UK, NICE has produced guidance on head injuries including when to perform a CT head scan.

Typical pathologies which may be shown on the CT scan include:

- Intracranial bleeds: extradural haemorrhage, subdural haemorrhage, subarachnoid haemorrhage and intracerebral haemorrhage

- Brain contusions

- Skull fractures

- Cerebral oedema

Any injuries identified on CT should be discussed with the neurosurgical team.

See our CT head interpretation guide for more details.

Interventions

Maintain the airway

Alert a senior immediately if you have any concerns about the consciousness level of a patient. A GCS of 8 or below warrants urgent expert help from an anaesthetist. In the meantime, you should re-assess and maintain the patient’s airway as explained in the airway section of this guide.

Opioid toxicity

If opioid toxicity is suspected as the cause for the patient’s reduced level of consciousness (e.g. pinpoint pupils) interventions such as naloxone should be considered.

See our opioid toxicity guide for more details.

Hypoglycaemia

The management of hypoglycaemia involves the administration of glucose (e.g. oral or intravenous).

See our hypoglycaemia guide for more details.

Re-assessment

Make sure to re-assess the patient following any intervention.

Exposure

It may be necessary to expose the patient during your assessment: remember to prioritise patient dignity and conservation of body heat.

Clinical assessment

Begin by asking the patient if they have pain anywhere, which may be helpful to guide your assessment.

Other injuries +/- bleeding

Fully expose the patient looking for evidence of other injuries or bleeding.

If active bleeding is identified:

- Estimate the total blood loss and the rate of blood loss.

- Re-assess for signs of hypovolaemic shock (e.g. hypotension, tachycardia, pre-syncope, syncope).

Temperature

Measure the patient’s temperature:

- Temperature >38°C may be due to infection. This may provide clues as to how the patient sustained the head injury (e.g. delirium secondary to infection in an elderly patient leading to a fall).

- Hypothermia (temperature < 36°C) may be seen in patients who have been immobilised by their injury for a prolonged period of time.

Interventions

Injuries

Treat other injuries identified and involve appropriate specialities (e.g. orthopaedics to reduce a fracture).

Explore any wounds and clean/close if confident to do so:

- Superficial lacerations may be closed with wound glue or wound closure strips

- Deeper or complex wounds may require sutures

Haemorrhage

If the patient is actively bleeding seek urgent senior input (e.g. surgical registrar, anaesthetics) and consider the need for blood products (e.g. packed red cells, platelets).

Large-bore intravenous access (x2) should be established and relevant blood tests should be sent (e.g. FBC, U&Es, coagulation studies, group and crossmatch) if not done so already.

In severe haemorrhage, consider initiating the major haemorrhage protocol (with senior approval).

See our blood transfusion guide for more details.

Warming

Consider warming (e.g. Bair Hugger™) in hypothermia (seek senior input).

CPR

If the patient loses consciousness and there are no signs of life on assessment, put out a crash call and commence CPR.

Re-assessment

Make sure to re-assess the patient after any intervention.

Reassess ABCDE

Re-assess the patient using the ABCDE approach to identify any changes in their clinical condition and assess the effectiveness of your previous interventions.

Deterioration should be recognised quickly and acted upon immediately.

Seek senior help if the patient shows no signs of improvement or if you have any concerns.

Support

You should have another member of the clinical team aiding you in your ABCDE assessment, such as a nurse, who can perform observations, take samples to the lab and catheterise if appropriate.

You may need further help or advice from a senior staff member and you should not delay seeking help if you have concerns about your patient.

Use an effective SBARR handover to communicate the key information effectively to other medical staff.

Next steps

Well done, you’ve now stabilised the patient and they’re doing much better. There are just a few more things to do…

Take a history

Take a thorough history to help narrow the differential diagnosis.

See our history taking guides for more details.

Review

Review the patient’s notes, charts and recent investigation results.

Review the patient’s current medications and check any regular medications are prescribed appropriately.

Regular review

Ask the nursing staff to perform regular neurological observations. Frequency depends on the extent of the injury and the patient’s condition.

Make a regular clinical review of the patient so any deterioration is identified quickly and acted upon.

Document

Clearly document your ABCDE assessment, including history, examination, observations, investigations, interventions, and the patient’s response.

See our documentation guides for more details.

Discuss

Discuss the patient’s current clinical condition with a senior clinician using an SBARR style handover.

Questions which may need to be considered include:

- Are any further assessments or interventions required?

- Does the patient need a referral to HDU/ICU?

- Does the patient need reviewing by a specialist (e.g. neurosurgery)?

- Should any changes be made to the current management of their underlying condition(s)?

Handover

The next team of doctors on shift should be made aware of any patient in their department who has recently deteriorated.

Reviewer

Dr Frances Balmer

ST4 in Emergency Medicine

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Head injury: assessment and early management. Published 2014, updated 2019. Available from: [LINK].

- Pixabay. Side on skull. License: [FFCU].

- Spinal injury: assessment and initial management. Published in 2016. Available from: [LINK].

- British Thoracic Society. BTS Guideline for oxygen use in adults in healthcare and emergency settings. Available from: [LINK].