- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Overview

The uterus is a female secondary sex organ located within the pelvis. This short article describes the normal anatomy of the uterus and will focus on definitions, structure, location, supporting ligaments, blood supply and innervation. The function of the uterine cervix during pregnancy is described at the end of the article. Check out the attached video to see uterine anatomy in 3D and to hear about the important relationships between uterine vasculature and the ureter for hysterectomy and ovariectomy.

Definitions

The uterus is a fibromuscular organ that is responsible for protecting and nurturing the developing conceptus. It is described as having two distinct parts: a muscular uterine corpus and a more fibrous uterine cervix. Definitions are important here, as it is easy to assume that the cervix is an entirely separate organ. Associated structures include the vagina, uterine (Fallopian) tubes and ovaries. Whilst not described in this article in great detail, tubal and vaginal anatomy are briefly described in the video associated with this page.

Structure of the Uterus

Uterine corpus

The corpus is the proximal muscular portion of the uterus. It is described as having 3 layers: the inner endometrium, the middle myometrium and the outer perimetrium.

- Endometrium: This is a highly plastic structure that undergoes regular morphological change during the menstrual cycle, due to the fluctuations in circulating oestrogen and progesterone. This layer sheds during the menstrual phase of the uterine cycle.

- Myometrium: This is a muscular portion of the uterus. The muscle fibres have been categorised based on the orientation within the myometrium i.e. circular, spiral and longitudinal.1 The contractions of these underlying fibres facilitate the compression of the uterine cavity during labour to push the fetus through the birth canal.

- Perimetrium: This is the outer serous layer of the uterus formed by the overlying peritoneum.

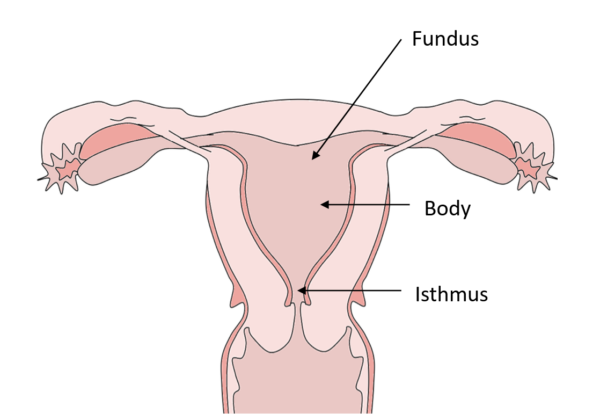

The corpus is also described as having a fundus (proximal), body (middle) and an isthmus (distal; Figure 1).

Cervix

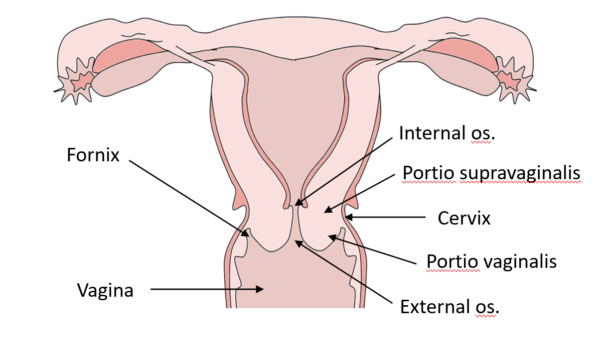

The cervix is the distal fibrous portion of the uterus. Two anatomical regions that lie above and below the vaginal reflection are described: the portio supravaginalis and portio vaginalis, respectively. The portio vaginalis projects into the anterior aspect of the vagina forming the vaginal fornices at the margin of the cervix (this relationship is especially important for culdocentesis, a procedure whereby peritoneal fluid is obtained via the pouch of Douglas.) The central cervical canal runs from the internal os to the external os (Figure 2).

Uterus Location and Anatomical Relations

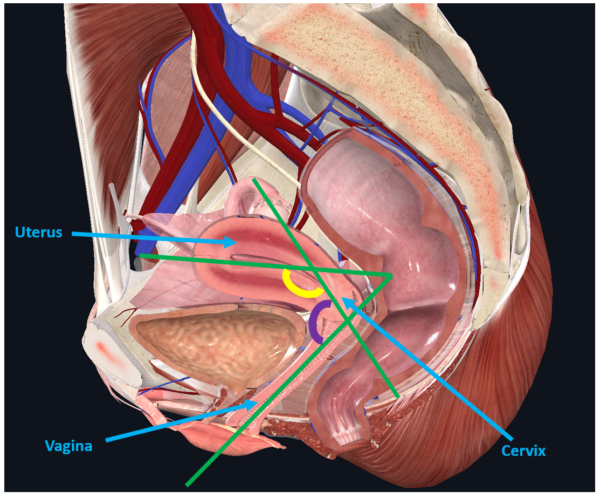

The non-pregnant uterus is located within the ‘true/lesser pelvis’ (i.e. below the pelvic brim), posterior (and superior) to the bladder and directly anterior to the rectum (Figure 3). The uterine corpus usually arches forward over the superior surface of the bladder, creating an angle of anteflexion between the corpus and the internal os. The projection of the cervix into the upper vagina creates an angle of anteversion between the two structures as well. Separating the bladder from the upper portion of the cervix is the perimetrium, which is reflected onto the base of the bladder forming the vesicouterine pouch. Posteriorly, the rectouterine pouch (of Douglas) is formed as a result of the peritoneal reflection from the cervix inferiorly to the posterior vaginal fornix and onto the rectum. Excess peritoneal fluid may collect in the rectouterine pouch as it is the most inferior ‘space’ within the female abdominopelvic cavity, such as in the case of suspected ruptured ovarian cyst or ectopic pregnancy. This excess fluid can be drained by culdocentesis.

Supporting Ligaments

There are several key supporting ligaments of the uterus. They are described further below.

Broad ligament

The broad ligament is formed by the overlying peritoneum ‘draping’ over the uterus and associated structures. It is further subdivided into the mesometrium, mesovarium and mesosalpinx (described in the attached video).

Round Ligament

The round ligament is a cord-like structure that extends from the corpus to the labia majora, via the inguinal canal. It is an extension of the ovarian ligament that passes from the ovary to the uterine corpus. Both of these ligaments are derivatives of the embryonic gubernaculum that extended from the gonads to the labia majora (females) or scrotum (males). The function of the round ligament may be to assist in maintaining the anteflexed position of the uterus.

Cardinal ligament

The cardinal ligaments pass from the cervix to the internal iliac artery, though alternative attachment sites at the iliac fossae, ischial spines and the broad ligament have been described.2 The cardinal ligament is a conduit for blood vessels and nerves that pass to or from the uterus and associated pelvic structures. The cardinal ligament likely provides support to the pelvic viscera, as structural abnormalities have been associated with pelvic organ prolapse.3

Uterosacral ligament

The uterosacral ligaments pass from the posterior and lateral supravaginal portions of the cervix to the middle three sacral vertebrae,4 though other attachments include levator ani, coccygeus and obturator internus.5 The ligament is thought to facilitate the passing of nerves to the pelvic viscera. However, it is likely to have limited supportive value, other than to maintain the natural anteverted position of the uterus.6,7

Blood Supply and Innervation

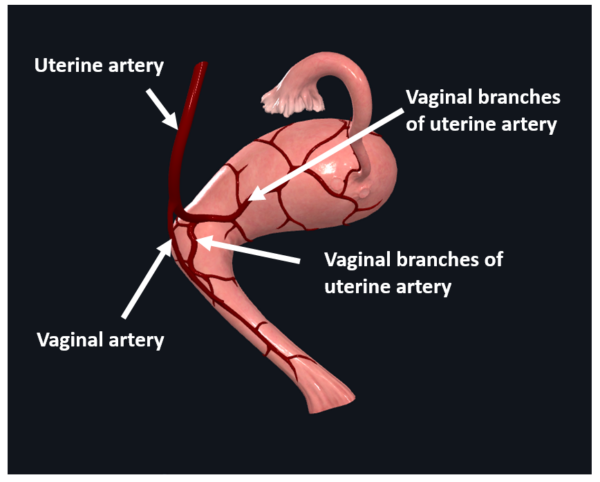

The uterus receives blood from branches of the internal iliac artery (Figure 4). Typically, the uterine artery arises from the internal iliac artery and passes towards the uterus. Just before reaching the uterus, a vaginal artery arises to descend the lateral wall of the vagina. At the uterocervical junction, the uterine artery divides into ascending and descending branches. The ascending branch supplies the corpus and uterine tubes, whereas the descending (vaginal) branch supplies the cervix and upper vagina. Great variation is often observed here, so a tip would be to trace branches of the internal iliac arterial system from source to destination (e.g. the vaginal artery often arises directly from the internal iliac artery). The veins typically follow the arteries.

The uterus is innervated via the inferior hypogastric plexus. This plexus receives post-ganglionic sympathetic fibres from the inferior hypogastric nerves (branches of the superior hypogastric nerve) and preganglionic parasympathetic fibres from pelvic splanchnic nerves from S2-S4. Most of the parasympathetic nerves will synapse in ganglion at the level of the uterus. Visceral afferent fibres pass within the pelvic splanchnic nerves.

This image was created using CompleteAnatomy [LINK]

The Cervix and Pregnancy

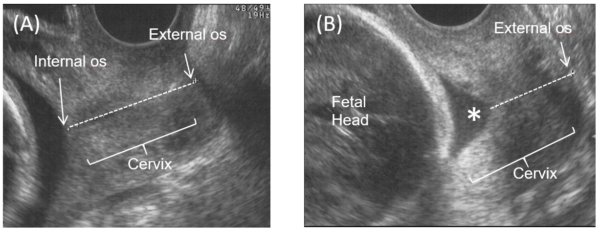

From conception, the functions of the cervix are to retain and protect the growing conceptus. However, towards term, the cervix must soften, shorten and dilate to allow for the passage of the foetus. If the cervix is structurally weak, it may open too early and lead to preterm birth. It is not known why this sometimes happens and it is especially difficult to determine if a woman has a weak cervix. A current method of identifying whether pregnant women might have cervical weakness is via transvaginal ultrasound. Clinicians are able to assess cervical length (a short cervix is associated with preterm birth) and degree of funnelling (degree of which the internal cervical os has dilated). The images below are transvaginal ultrasound scans showing a closed internal os (Figure 5A) and cervical funnelling (Figure 5B).

References

- Weiss S, Jaermann T, Schmid P, Staempfli P, Boesiger P, Niederer P, et al. Three-dimensional fiber architecture of the nonpregnant human uterus determined ex vivo using magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging. Published in 2006. [LINK]

- Ramanah R, Berger MB, Parratte BM, DeLancey JOL. Anatomy and histology of apical support: a literature review concerning cardinal and uterosacral ligaments. Published in 2012.[LINK]

- Ewies AAA, Al‐Azzawi F, Thompson J. Changes in extracellular matrix proteins in the cardinal ligaments of post-menopausal women with or without prolapse: a computerized immunohistomorphometric analysis. Published in 2003. [LINK]

- Singer A, Jordan J. The functional anatomy of the cervix, the cervical epithelium and the stroma. Published in 2006. [LINK]

- Blaisdell FE. The anatomy of the sacro-uterine ligaments. Published in 1917. [LINK]

- Campbell RM. The anatomy and histology of the sacrouterine ligaments. Published in 1950. [LINK]

- Ramanah R, Parratte B, Arbez-Gindre F, Maillet R, Riethmuller D. The uterosacral complex: ligament or neurovascular pathway? Anatomical and histological study of fetuses and adults. Published in 2008. [LINK]