- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Brugada syndrome is a rare autosomal-dominant inherited cardiac sodium channelopathy, characterised by ST-segment elevation in at least one of the anterior precordial leads (V1-V3) in the context of a structurally normal heart.1

Patients are at high risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD) secondary to polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) or ventricular fibrillation (VF).1

This is a relatively new syndrome that was first described in 1993 by Brugada. Eight patients with structurally normal hearts had recurrent episodes of aborted cardiac arrest secondary to polymorphic VT that could not be explained by known diseases.2

Aetiology

Traditionally, Brugada syndrome has been described as having an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern. However, it is worth noting that a recent paper published in BMJ Heart stated that “while Brugada syndrome was initially thought to be inherited as a monogenic, autosomal dominant disease requiring only one mutation, it is now considered more likely to encompass an oligogenic or polygenic inheritance, in which multiple ‘genetic modifiers’ either exacerbate or alleviate the phenotypical expression of the primary genetic defect.”3

The genotype-phenotype relationship of Brugada syndrome is highly complex and is yet to be fully understood.

Multiple gene mutations have been implicated in Brugada syndrome, but only variants of the SCN5A gene are considered pathogenic.4,5 SCN5A gene encodes the alpha subunit of the cardiac voltage-gated sodium channel (Nav1.5).6 Over 300 mutations of the SCN5A gene have been discovered so far.7

It is now known that other genes apart from SCN5A play a role in Brugada syndrome. Only ~20% of patients with Brugada syndrome were found to have mutations in SCN5A.4,8

Furthermore, SCN5A mutations are also known to be implicated in other cardiac conditions, including long QT syndrome type III, sick sinus syndrome, progressive cardiac conduction diseases, dilated cardiomyopathy etc.1

Pathophysiology

Mutations in the SCN5A gene result in defective Nav1.5 channels in the cardiac cell membrane, which play a crucial role in the initial depolarisation phase (phase zero) of the cardiac action potential. This loss of function leads to a delayed phase zero, causing slower conduction in the heart and increasing the risk of developing ventricular arrhythmias.

Although the precise mechanism is not fully understood, two main hypotheses have been proposed: the repolarisation and the depolarisation disorder models. Both theories emphasise the involvement of the right ventricle, particularly the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT), which accounts for the distinctive ECG changes observed in the right precordial leads (V1-V3).1,3,5,9

Risk factors

Brugada syndrome is found to be more common in:5,10

- Male (~8-10 times more prevalent than female)

- Middle age (30-50 y/o)

- Asian ancestry, especially Southeast Asia (leading cause of death in male <40 in Southeast Asia)

- Positive family history

Clinical features

Two-thirds of patients are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis, making the diagnosis of Brugada syndrome challenging.5 No specific clinical features are known to be highly specific to Brugada syndrome.

The following selected points of clinical history and family history are based on the Shanghai Score System for diagnosing Brugada syndrome. See the diagnosis paragraph for more details.

History

There are three main clinical manifestations of symptomatic Brugada syndrome:4,5

- Cardiogenic syncope

- Unexplained cardiac arrest (usually during sleep or at rest, unlike in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy where cardiac arrest usually happens during physical activity)

- Documented polymorphic VT or VF

Some other clinical features associated with Brugada syndrome:4,5

- Atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter at <30 y/o

- Nocturnal agonal respirations

In patients who present with syncope, detailed clinical assessment is necessary to differentiate between other potential mimics like vasovagal syncope.

As mentioned, most patients are asymptomatic. The Brugada syndrome phenotype may only manifest when induced by certain triggers. It is important to screen for the following:4,5

- Febrile illness (cardiac action potential is further shortened at high temperatures, thus further slowing conduction in the RVOT)

- Use of medications with sodium channel blockage – antiarrhythmics, anaesthetics, antipsychotics

- Excessive alcohol intake

- Use of illicit drugs like cannabis and cocaine

A detailed family history should be explored in cases of suspected Brugada syndrome. It is important to ask if any of the following is present in first or second degree relatives:4,5

- Definite Brugada syndrome

- Unexplained SCD in <45 y/o with negative autopsy

- Suspicious SCD (febrile induced, nocturnal death, Brugada-aggravating drug)

Clinical examination

Physical examination of patients with Brugada syndrome is usually normal. In the context of suspected Brugada syndrome, it is important to check one’s temperature to exclude febrile illness.

A full cardiovascular examination should always be performed in all patients to exclude other potential underlying cardiovascular pathologies and pectus excavatum, a potential cause of type I Brugada ECG pattern.

Investigations

Bedside investigations

ECG

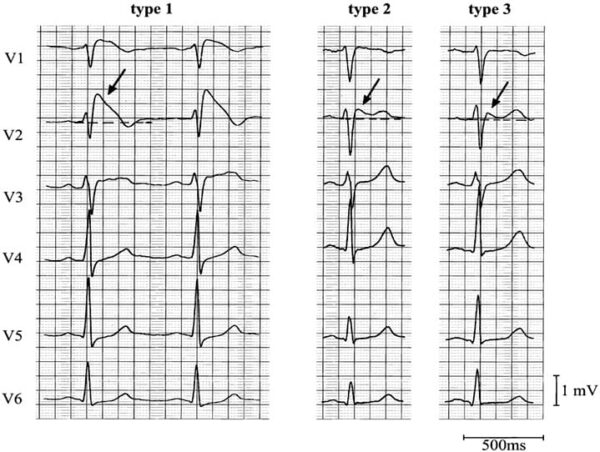

There are three recognised ECG patterns in Brugada syndrome. Type I is the only diagnostic ECG change.1,5,11 The following ECG changes must be observed in at least one lead in V1-V3 (right precordial leads).11

Type 1 Brugada ECG pattern:

- ST-T configuration – coved-type ST elevation

- J wave amplitude ≥ 2mm

- Negative T wave

Type 2 Brugada ECG pattern:

- ST-T configuration – saddle-back ST elevation (rSr’ pattern)

- J wave amplitude ≥ 2mm

- Positive or biphasic T wave

Type 3 Brugada ECG pattern:

- Right precordial ST-segment elevation

- Coved type, saddle-back type, or both

- Not meeting the above criteria

High precordial lead ECG positions

High precordial leads increase the sensitivity of detecting the Brugada ECG changes due to individual variations in the RVOT anatomical position. It is thought to increase the diagnostic yield by ~1.5 times compared with standard lead positions.5

High precordial lead positions are as follows:

- hV1 and hV2 at 2nd intercostal space

- hV3 and hV4 at 3rd intercostal space

- hV5 and hV6 at 4th intercostal space

As such, hV5 and hV6 are equivalent to V1 and V2 in a standard ECG lead placement.

Drug provocation testing

Drug provocation testing can unmask Brugada syndrome. Authors of a review paper on Brugada syndrome published in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology recommends drug provocation testing in patients with:5

- Baseline type 2 or 3 Brugada ECG

- Suspected Brugada syndrome based on clinical or family history

Note that drug provocation testing is not recommended in patients with spontaneous type 1 Brugada ECG at baseline, as it has no additional diagnostic value.5

The drug class of choice is sodium channel blockers (SCBs). Four SCBs are routinely used for provocation testing.5 They all have a predominant action on inhibiting the Nav1.5:

- Ajmaline (class Ia antiarrhythmic) – mainly used in Europe

- Flecainide (class Ic antiarrhythmic) – mainly used in Europe

- Procainamide (class Ia antiarrhythmic) – mainly used in North America

- Pilsicainide (class Ic antiarrhythmic) – mainly used in Japan

The administration of SCBs may exaggerate or unmask Brugada ECG changes. During the drug provocation testing, a series of ECGs should be taken:4,5,11

- Baseline – before the infusion

- During the infusion

- After the infusion

Laboratory investigations

Genetic testing

Currently, only genetic testing for variants in the SCN5A gene is performed. It is important to note that the yield of genetic testing in diagnosing Brugada syndrome is only ~20%.4,8

The sole presence of a probable pathogenic SCN5A mutation is not diagnostic of Brugada syndrome, it only scores 0.5 in the Shanghai Score System. Genetic testing is not routinely offered and should only be used as an adjuvant in family screening.5

Imaging

Baseline echocardiogram

An echocardiogram should be performed in all patients as part of their work-up for Brugada syndrome to exclude underlying structural heart disease that may have caused their presentation.5,12

Expected echocardiogram findings in Brugada syndrome is no abnormalities with or without structural abnormalities in the right ventricle or RVOT.5,12

Cardiac CT or MRI

Advanced cardiac imaging like CT or MRI are not routinely performed nor required to diagnose Brugada syndrome.

It is usually used to help differentiate Brugada syndrome from other differentials like arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy.12

Other investigations

Electrophysiological study (EPS) with programmed electrical stimulation (PES)

The main indication of performing EPS in Brugada syndrome is risk stratification to guide management. However, recommendations regarding the use of EPS remain controversial:

- Authors of a consensus report on the proposed diagnostic criteria for Brugada syndrome published in Circulation recommends EPS in all symptomatic patients.11

- Authors of a review paper on Brugada syndrome published in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology do not recommend the routine use of EPS with PES for risk stratification in Brugada syndrome.5

The latter recommendation is because of results from two recent large prospective multicentre registries, FINGER (France, Italy, Netherlands, Germany) and PRELUDE (Programmed Electrical stimulation predictive value), who failed to validate the role of EPS with PES in Brugada syndrome.5

Diagnosis

According to both the ESC (European Society of Cardiology) guidelines and the Shanghai Score System, Brugada syndrome can be diagnosed in the presence of spontaneous type 1 Brugada ECG pattern (observed in standard ECG lead positioning or high precordial lead positioning) in the absence of other heart diseases, regardless of symptoms.4,5

If the above criteria are not fulfilled, other factors must be considered to reach or exclude a diagnosis. A consensus conference report published in 2017 developed the Shanghai Score System for Diagnosis of Brugada Syndrome for such purposes.13

The Shanghai Score System considers four aspects:

- Clinical history

- Family history

- ECG findings

- Genetic testing result

Differential diagnoses

Conditions that can give rise to a similar type 1 Brugada ECG pattern include:11,12,14

- Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) (right coronary artery or left anterior descending artery infarction)

- Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC)

- Incomplete right bundle branch block (RBBB)

- Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH)

- Mechanical compression of RVOT (e.g., pectus excavatum, mediastinal tumour)

- Electrolyte disturbances (e.g., hyperkalaemia, hypokalaemia, hypercalcaemia)

Conditions that can give rise to a similar type 2/3 Brugada ECG pattern include:11,12,14

- Early repolarisation syndrome (ERS)

- Athlete’s heart

Management

There is currently no cure for Brugada syndrome. Current management aims to prevent SCD with ICD implantation.

Conservative management

Lifestyle advice

The following advice should be communicated to all patients:4,5,12

- Avoidance of Brugada-aggravating drugs, important drug classes include antiarrhythmics, anaesthetics and antipsychotic drugs

- Prompt treatment of fever with antipyretic drugs

- Avoidance of cocaine, cannabis, and excessive alcohol intake

- Avoid sleeping immediately after eating big meals

Family screening

Screening should be offered to 1st-degree relatives of a newly diagnosed Brugada syndrome patient or those with unexplained SCD.4,5,12

Family screening for Brugada syndrome should entail:4,5

- Adults: standard and high precordial lead ECG and consider drug provocation test.

- Children: standard and high precordial lead ECG at 3 y/o, every three years until 15 y/o. Drug provocation test should not be offered until they are older than 15 y/o.

If the drug provocation test is negative, there is no need for additional testing and follow-up.

Pharmacological management

Quinidine

Quinidine is a class 1a antiarrhythmic that inhibits cardiac voltage-gated sodium channels to decrease phase zero of rapid depolarisation. Its most important antiarrhythmic effect in Brugada syndrome is its ability to prolong the effective refractory period.5

Quinidine is useful in suppressing ventricular arrhythmia, it should be considered in the following patients:4,12

- ICD indicated but not implanted due to contraindications or patient preferences

- ICD implanted but experiencing recurrent shocks

- Asymptomatic spontaneous type 1 Brugada ECG

- History of electrical storm (>2 episodes of VT or VF within 24 hours)

- History of asymptomatic ventricular arrhythmia

Interventional management

Implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD)

The implantation of an ICD is the only current intervention that reduces the risk of SCD in Brugada syndrome.4 The 2022 ESC Guidelines regarding ICD implantation for SCD prevention are summarised below.4

ICD implantation is recommended in the presence of (class I indication):

- Prior aborted cardiac arrest

- Documented spontaneous sustained VT

ICD implantation should be considered in the presence of (class IIa indication):

- History of cardiogenic syncope with type 1 Brugada ECG

ICD implantation may be considered in the presence of (class IIb indication):

- Inducible VF during EPS with PES using up to two extra stimuli

Catheter ablation

Ablation of abnormal areas with fibrotic arrhythmogenic substrate in the epicardial RVOT can supress recurrent VF and normalise the ECG in >75% of patients.4,5 Prior EP mapping could help identify these areas.

Selected points regarding the recommendation of catheter ablation in patients with Brugada syndrome:

- Consider in patients with recurrent ICD shocks that is refractory to pharmacological therapy.4

- Consider in patients where an ICD is indicated but not implanted due to contraindications or patient preferences.5

- Not recommended in asymptomatic patients.4

Complications

Arrhythmia-related complications include:12

- Polymorphic VT

- VF

- Sudden cardiac death

- Cardiogenic syncope

- Atrial arrhythmias (e.g., new-onset atrial fibrillation)

ICD-device related complications include:15

- Procedure-related complications – pneumothorax, haematoma

- Physiological and physical impact

- Lead malfunction

- Infection

- Inappropriate shocks

Key points

- Brugada syndrome is an autosomal dominant sodium channelopathy of the heart associated with mutations in the SCN5A gene.

- Patients with Brugada syndrome are at high risk of SCD secondary to polymorphic VT or VF

- Patients can be completely asymptomatic or present as cardiogenic syncope, cardiac arrest, or SCD.

- The only diagnostic ECG finding is spontaneous type 1 Brugada ECG, defined as a coved-ST elevation ≥ 2mm followed by an inverted T wave in ≥1 leads in V1-V3.

- In the absence of spontaneous type 1 Brugada ECG, diagnosis should be guided by the Shanghai Score System, taking clinical history, family history, ECG finding and genetic testing into account.

- There is no curative treatment for Brugada syndrome, the mainstay management is ICD implantation to prevent SCD.

- Patient education is important to avoid aggravation of Brugada syndrome phenotype, importantly avoidance of certain drugs and prompt management of fever.

Reviewer

Dr John Bonello

Specialist in cardiology

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Mizusawa Y, Wilde AAM. Brugada Syndrome. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology 2012 Jun;5:606-616.

- Brugada P, Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: A distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome: A multicenter report. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 1992 Nov;20(6):1391-1396.

- Marsman EMJ, Postema PG, Remme CA. Brugada syndrome: update and future perspectives. Heart 2022 Apr;108:668-675.

- Zeppenfeld K, et al. 2022 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: Developed by the task force for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Endorsed by the Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC). European Heart Journal 2022 Oct;43(40):3997-4126.

- Krahn AD, et al. Brugada Syndrome. Journal of the American College of Cardiology: Clinical Electrophysiology 2022 Mar;8(3):386-405.

- Brugada R, et BRUGADA SYNDROME. Methodist Debakey Cardiovascular Journal 2014 Jan-Mar;10(1):25-28.

- Attard A, et al. Brugada syndrome: should we be screening patients before prescribing psychotropic medication? Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology 2022 Jan;12: 20451253211067017.

- Kapplinger JD, et al. An international compendium of mutations in the SCN5A-encoded cardiac sodium channel in patients referred for Brugada syndrome genetic testing. Heart Rhythm 2010 Jan;7(1):33-46.

- Meregalli PG, Wilde AAM, Tan HL. Pathophysiological mechanisms of Brugada syndrome: depolarization disorder, repolarization disorder, or more? Cardiovascular Research 2005 Aug;67(3):367-378.

- Bayés de Luna A, Brugada J, Baranchuk A, et al. Current electrocardiographic criteria for diagnosis of Brugada pattern: a consensus report. J Electrocardiol. 2012;45(5):433-42.

- Wilde AAM, et al. Proposed Diagnostic Criteria for the Brugada Syndrome. Circulation 2022 Nov;106(19):2514-2519.

- BMJ Best Practice. Brugada syndrome. Reviewed 2024 Feb; updated 2023 Aug. Available from: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/3000313

- Antzelevitch C, et al. J-Wave syndromes expert consensus conference report: Emerging concepts and gaps in knowledge. EP Europace 2017 Apr;19(4):665-694.

- Snir AD, Raju Hariharan. Current Controversies and Challenges in Brugada Syndrome. European Cardiology Review 2019 Dec;14(3):169-174.

- Ezzat VA, et al. A systematic review of ICD complications in randomised controlled trials versus registries: is our ‘real-world’ data an underestimation? Open Heart 2015 Feb;2(1):e000198.

Image references

- Figure 1. Life in the fast lane. Brugada Syndrome. License: [CC-BY-NC-SA]