- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

This worksheet helps to guide you through a hypothetico-deductive reasoning process. It is designed to help you make the most of every patient encounter and to recognise opportunities to develop clinical reasoning.

At each stage of your clinical assessment, the worksheet encourages reflection and refinement of reasoning processes. Before getting started, make sure you’ve read our introduction to clinical reasoning page to familiarise yourself with the important concepts.

Consider taking this worksheet with you on clinical placements to guide your approach to assessing and discussing the management of a patient. This may be particularly helpful when you have less structured time during clinical attachments. You could use it as the foundation of case-based discussions with clinical supervisors.

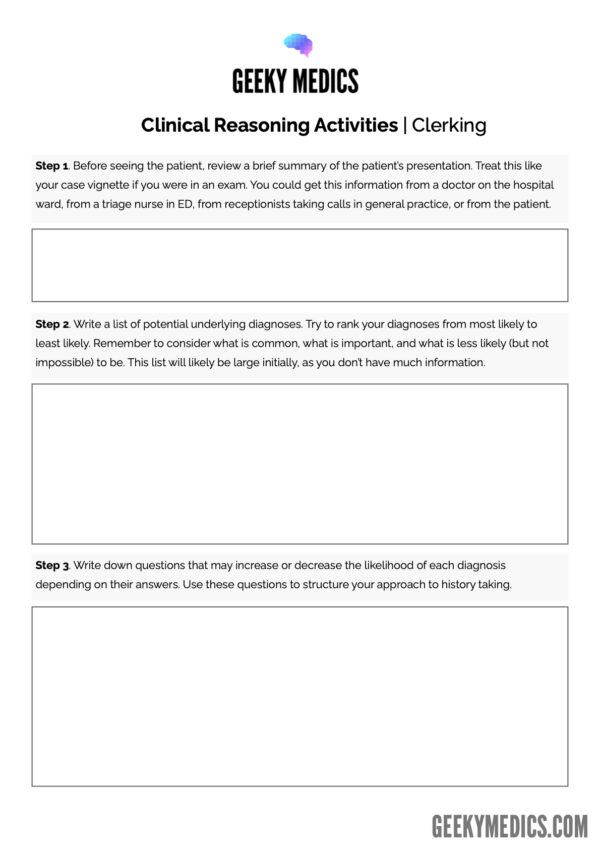

Clinical reasoning patient clerking approach

This approach outlines how to develop your clinical reasoning skills during every patient encounter.

1. Before seeing the patient, review a brief summary of the patient’s presentation. Treat this like your case vignette if you were in an exam.

2. Write a list of potential underlying diagnoses. Remember to consider what is common, what is important, and what is less likely (but not impossible) to be. This list will likely be large initially, as you don’t have much information.

3. Based on the information you have in your vignette, try to rank your diagnoses from most likely to least likely.

- This order might change, but it will help you to get started.

- Think about why you have ranked them in this way. Is it based on epidemiological data (i.e. what is common at a population level)? Is it based on the patient demographics such as age, gender or ethnicity (i.e. certain conditions are more common in patients with certain ethnic backgrounds)?

4. Starting from the top of the list, write down questions that may increase or decrease the likelihood of each diagnosis depending on their answers.

- You may be able to identify questions that will completely rule out certain diagnoses.

- Remember to include questions about past medical history, drug history, family history and social history as well as just the history of presenting complaint.

- It may be just as crucial to get a ‘no’ in response to a question (an important negative) as it is to get a ‘yes’ in response to a question (an important positive).

5. Use these questions to structure your approach to history taking from the patient. Keep re-evaluating your questions as new information comes to light to see if you need to ask anything new.

6. Once you have collected your information through history taking, review your list of potential diagnoses.

- Strike out any diagnoses you feel have been ruled out by the history.

- Re-order your ranking if the information you collected has altered the likelihood of your diagnoses.

- You can add to the list, too, if new information has led to new ideas.

7. Starting again from the top of the list, write down examination findings that would increase or decrease the likelihood of each diagnosis. Again, you may be able to identify pathognomonic signs or signs that will rule out certain diagnoses.

8. Use these signs/findings to decide which focused examinations to perform.

- As you examine the patient, you should actively look for important positive and negative findings to narrow down your differentials.

9. Once you have collected the information from the examination, review your list again.

- Strike out any diagnoses you feel have been ruled out by your examination findings.

- Re-order your ranking if the information you collected has altered the likelihood of your diagnoses.

- You can add to the list if new information has led to new ideas.

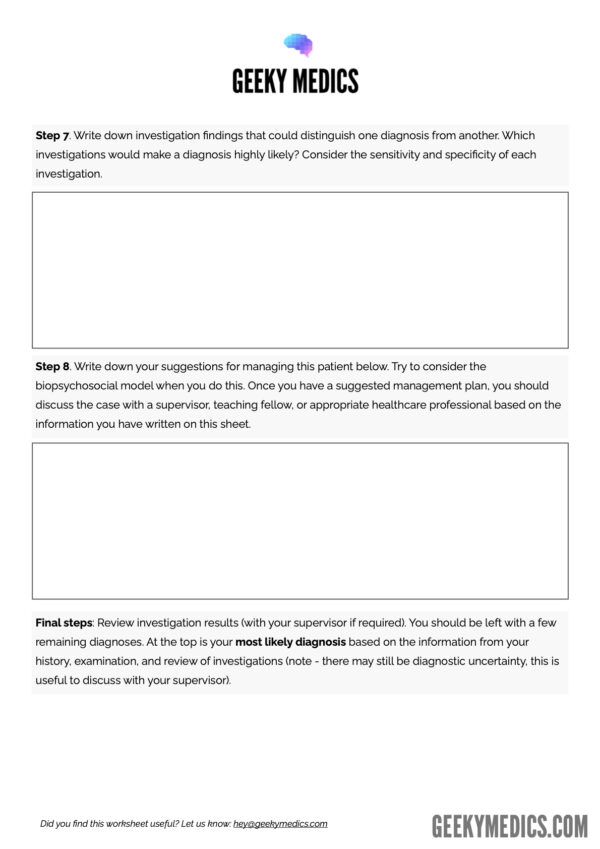

10. Starting at the top of your list for the last time, write down investigations that could distinguish one diagnosis from another.

- Which investigations would make a diagnosis highly likely?

- Are there any investigations that would be 100% diagnostic?

- Are there any investigations that would absolutely rule out certain diagnoses?

- Consider the sensitivity and specificity of the investigations and whether this affects their usefulness.

- Ensure that every investigation you request will give you a useful answer (Note: A useful answer may be a normal result).

11. Write down your suggestions for managing the patient. Try to consider the biopsychosocial model when you do this.

12. Review the results of your patient’s investigations (with a nominated clinician/supervisor if required by your institution). See whether the results confirm or rule out any of your diagnoses.

You should be left with a few remaining diagnoses. At the top is your most likely diagnosis based on the information from your history, examination, and review of investigations.

There may be some other diagnoses that you have not been able to rule out completely, but in most cases, you are likely to be confident in your primary differential and can, therefore, go forward to discuss a management plan using evidence-based guidelines and integrating shared decision-making.

Worksheet

Download the Geeky Medics clinical reasoning clerking worksheet. This worksheet is designed to help you develop your clinical reasoning skills when seeing patients.

Managing uncertainty

In some situations, history, examination, and investigations do not provide sufficient clarity about the likely diagnosis, making it difficult to decide the direction of treatment.

At this point, clinicians must make an informed decision about the most appropriate course of action:

- You could consider further specialist tests.

- You could consider treating the most common condition because it is the most common.

- You need to consider the risks of not treating the other conditions.

- You could trial a treatment and use this to determine whether there is a response to treatment, which may confirm the diagnosis.

- You could consider whether there are some management approaches which may treat several of the potential diagnoses.

- You could consider watchful waiting.

It may be appropriate to share this uncertainty with the patient and communicate that there is not always a clear answer. This provides a valuable opportunity for shared decision-making.

This is where much more complex clinical reasoning and shared-decision making comes into play.

It is normal to feel uncomfortable when met with clinical uncertainty. In this situation, it is always best to discuss with colleagues and seniors. They should be able to offer support or guidance.