- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

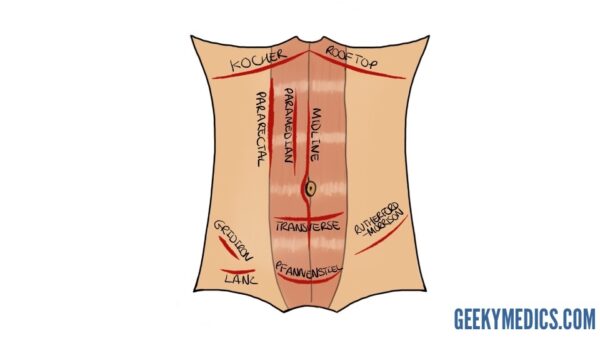

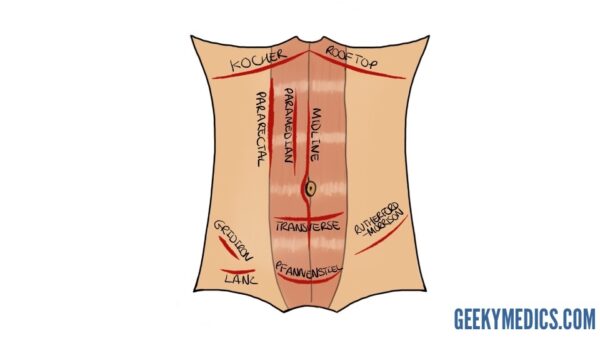

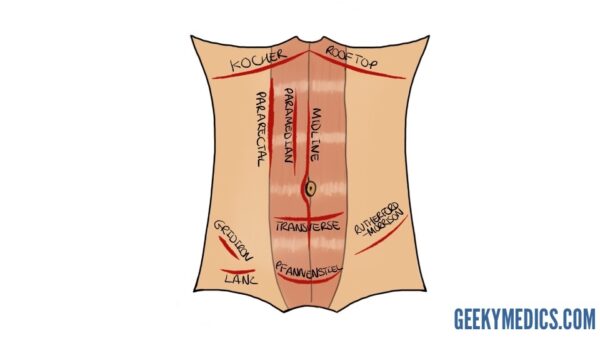

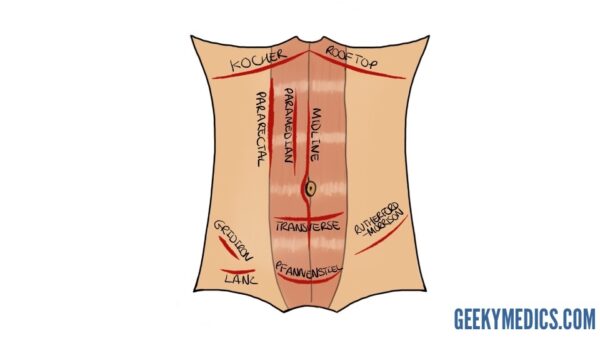

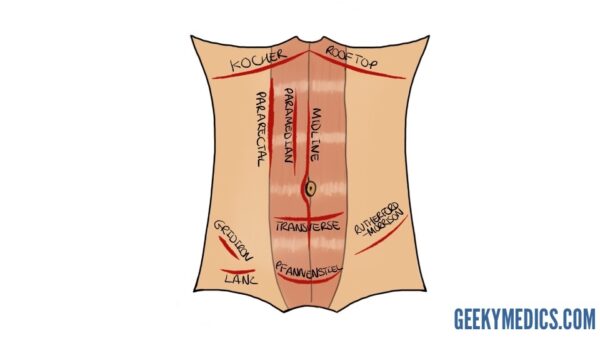

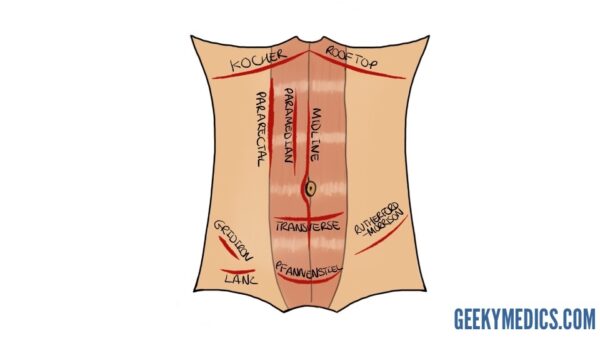

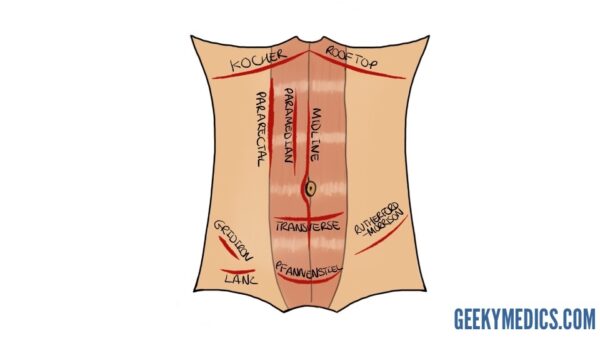

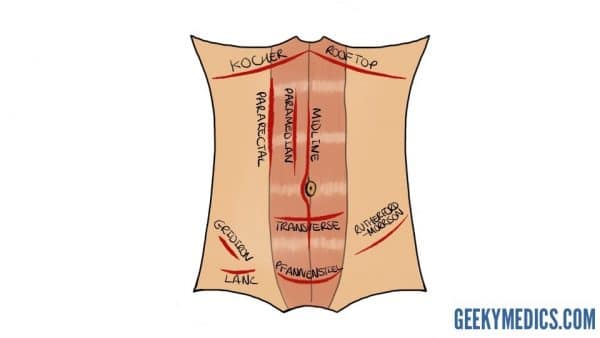

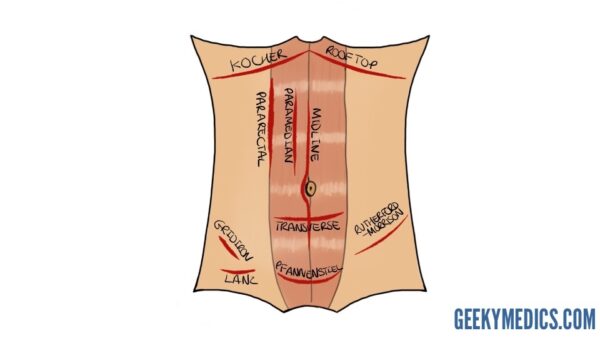

This article discusses the anatomy of the abdominal wall, anatomy of the rectus sheath and common abdominal surgical incision types (midline, paramedian, pararectal, Gridiron, Lanz, Pfannenstiel, transverse, Kocher).

The abdominal cavity is an ovoid space bounded cephalad by the diaphragm and inferior thoracic margin, caudally by the pelvic brim, posteriorly by the lumbar spine along with quadratus lumborum, psoas major and iliacus, and anterolaterally by the retaining musculature of the abdominal wall. The muscles of the abdominal wall play a major role in supporting ventilation, forcing the diaphragm cephalad in order to increase intrathoracic pressure to aid expiration, and allowing it to contract into the abdomen to decrease pressure for inspiration.

Within the abdomen lie the majority of the digestive tract and associated structures such as the liver, biliary tree, pancreas, kidneys and ureters, and the occasional pair of surgeons’ hands.

Check out the abdominal wall anatomy quiz here.

Anatomy of the abdominal wall

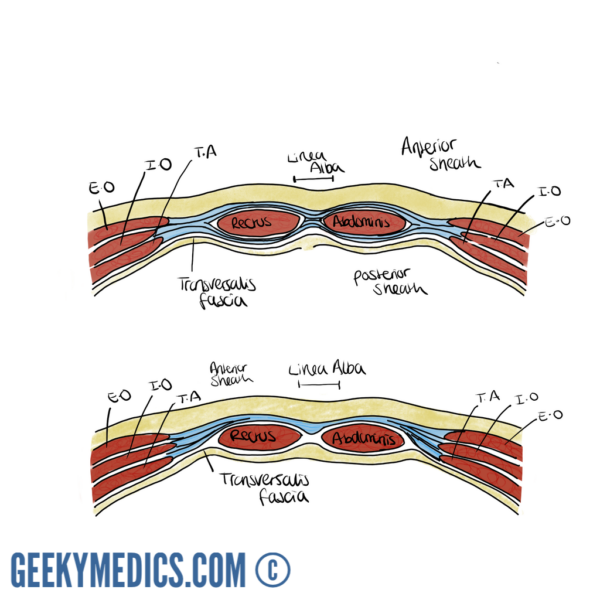

The lateral abdominal walls are formed by a triad of muscles: the external oblique (E.O), with its fibres running inferomedially like the fingers of the hands placed into the front pockets of one’s jeans; the internal oblique (I.O) with its fibres running orthogonally to its external relation, and transversus abdominis (T.A) with its horizontal fibres. Superficial to the external oblique lies Scarpa’s membranous fascia, Camper’s subcutaneous fatty layer, and the skin. Deep to transversus abdominis, the transversalis fascia encircles the preperitoneal fat and parietal peritoneum.

Incisions through the anterolateral wall will, therefore, breach the following structures:

- Skin

- Subcutaneous fatty layer

- Membranous fascia

- External oblique

- Internal oblique

- Transversus abdominis

- Transversalis fascia

- Preperitoneal fat

- Parietal peritoneum

As the fibres of the lateral abdominal wall muscles progress medially they give rise to fibrous sheets of tissue known as aponeuroses, allowing a far wider area of insertion than would be achievable with the typically round tendons seen on muscles of the appendicular skeleton. The internal oblique is unique in that its aponeurosis divides into an anterior and posterior leaf, the relevance of which will become clear later. These aponeuroses combine and interdigitate in such a way as to invest the paired longitudinal rectus abdominis muscles, forming the anterior midline structure known as the rectus sheath.

The rectus sheath

The paired rectus abdominis muscles originate from the anterior bony pubic bones toward the midline and run cephalad to insert onto the xiphisternum and costal cartilages of ribs 5-7. They derive their blood supply from the superior and inferior epigastric arteries from the internal thoracic and external iliac arteries respectively, and their innervation from the anterior rami of spinal nerve roots T7-T12.

The rectus sheath may be considered as having three distinct sections:

1. For most of the length of the paired recti, the anterior sheath is formed by the external oblique and anterior leaf of the internal oblique aponeuroses. The recti are interrupted by three paired tendinous intersections anchoring them to the anterior sheath, broadly found close to the xiphisternum, at the level of the umbilicus and then halfway between the two.

The posterior sheath is formed by the posterior leaf of the internal and the transversus abdominis aponeuroses and bears the superior and inferior epigastric arteries and their anastomotic network. The aponeurotic components of the sheath interdigitate in a thickened fibrous midline raphe between the two recti known helpfully as the linea alba (‘white line’). An elastic defect in this raphe may allow the fascia to stretch and abdominal contents to bulge forward through the resulting divarication of the recti. This produces a distinct ridge in the midline on increasing intra-abdominal pressure that is often mistaken for an epigastric hernia.

Point defects in the aponeurotic intersections of the linea alba may facilitate the development of epigastric hernias, which often simply contain preperitoneal fat but are often disproportionately painful for their size owing to their high tendency to strangulate.

2. There is no posterior sheath above the level of the costal margin, as the recti remain covered anteriorly by the external oblique aponeurosis and insert directly onto the underlying costal cartilages.

3. Roughly one-third to halfway between the umbilicus and the pubic symphysis lies the arcuate line (of Douglas), which is the point at which the posterior elements of the sheath perforate to join the anterior sheath and leave the thickened transversalis fascia in direct contact with the rectus muscles. The sheath is bounded laterally by the linea semilunaris, which is the longitudinal margin at which the internal oblique aponeuroses bifurcate to form anterior and posterior leaves. Defects in the integrity of the internal oblique may give rise to the formation of Spigellian hernias, allowing protrusion of the peritoneal sac into the rectus sheath. On examination, the patient may have a palpable lump close to the lateral border of the rectus sheath, commonly at the level of Douglas. The superficial nature of these hernias makes them amenable to diagnosis by ultrasonography.

Abdominal incisions

Many surgical procedures may now be performed laparoscopically with generally better results in terms of cosmesis, postoperative pain, recovery time and thus reduced length of stay and more expedient return to function when compared with traditional open techniques. There are still occasions where an open approach is required for speed, ease of access to relevant structures or in situations where laparoscopic equipment is unavailable. Some common incision sites are discussed below.

Midline incision

This common approach may be used to access most intra-abdominal structures, including those of the retroperitoneum. It utilises the relatively avascular nature of the linea alba to access the abdominal contents without cutting or splitting muscle fibres in the process, with the exception of the small pyramidalis muscle at the pubic crest. In some cases, there will be anastomotic branches of the superior and inferior epigastric vessels crossing from either side, but the incision generally avoids major neurovascular bundles.

Further advantages include the ease with which the incision may be extended either cephalad or caudally in order to improve access. Disadvantages include patients experiencing more pain than they would from a transverse incision, particularly during deep breathing postoperatively, and the incision is perpendicular to the Langer’s skin tension lines resulting in poorer cosmesis. This approach is commonly used for procedures requiring emergency laparotomy, such as in faecal peritonitis secondary to malignant intestinal perforation or in cases of ischaemic bowel. Limited midline incisions are also employed to assist laparoscopic cases such as bowel resections, where the dissection and mobilisation of the specimen to be excised are performed laparoscopically but then a larger port is required for retrieval.

A midline incision will thus encounter the following layers of tissue:

- Skin

- Subcutaneous fatty layer (Camper’s fascia)

- Membranous fascia (Scarpa’s)

- Linea alba

- Transversalis fascia

- Preperitoneal fat

- Parietal peritoneum

Paramedian incision

The scar of a paramedian incision may be seen running parallel to the midline in a limited number of patients but has fallen from common practice in favour of the midline incision due to its complexity and poor cosmesis. The falciform ligament of the liver is commonly encountered if the incision is made to the right of the midline, and the tendinous intersections must be divided on the chosen side in order to access the peritoneum.

Pararectal incision

Like the paramedian approach, the pararectal incision has now largely been abandoned. Disadvantages include disruption of the innervation to the rectus lying medially.

Gridiron incision

A gridiron incision involves an arcing incision through the skin, subcutaneous fat and fascia, external and internal obliques, transversus abdominis and transversalis fascia. It is commonly used for open appendicectomies. The incision is centred over McBurney’s point two-thirds of the distance between the umbilicus and the right anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), where the base of the appendix is most likely to be found. This classically corresponds to the area of maximal tenderness on clinical examination when the appendix has become sufficiently inflamed to cause localised peritonitis. This incision may be modified to follow the horizontal Langer’s lines for improved cosmesis. Disadvantages include the risk of injury to the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves. The arc may be extended cephalad and laterally in order to facilitate access to the ascending colon, which is known as the Rutherford-Morison incision.

Lanz incision

The Lanz incision was designed to be more cosmetically subtle than the gridiron, with the benefit that it may be hidden beneath the bikini line but the disadvantage of commonly severing the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves.

Pfannenstiel incision

The Pfannenstiel incision is a firm favourite of obstetricians for accessing the gravid uterus for which a curvilinear incision is made through the skin and subcutaneous fat, then a longitudinal incision made in the linea alba. It is also used by general and urological surgeons for some pelvic procedures such as radical open prostatectomy or cystectomy.

Transverse incision

A transverse incision is a useful laparotomy technique for use in paediatric patients who have not yet developed deep subphrenic or pelvic recesses, and in whom the surgeon, therefore, does not need the ability to extend the incision longitudinally as afforded by the midline incision. This incision is also commonly utilised by vascular surgeons for elective and emergency repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms.

Kocher incision

A Kocher incision is made parallel to the subcostal margin to access the underlying liver and biliary tree. It is commonly used for open cholecystectomy. It may be mirrored on the contralateral side to provide access to the spleen or performed bilaterally as a Rooftop incision to provide efficient access to organs such as the pancreas and biliary tree within the transpyloric plane (see below). Disadvantages include the risk of injuring the superior epigastric vessels, and lateral extension of the incision risks disruption of intercostal nerves.

Structures within the transpyloric plane:

- L1 vertebral body

- Tip of the 9th costal cartilage

- Fundus of the gallbladder

- Duodeno-jejunal flexure

- Pylorus of the stomach

- The neck of the pancreas

- Renal hila

- Conus of the spinal cord

Complications of abdominal surgical incisions

Complications are best considered in terms of specificity and chronicity; i.e. generic complications of surgery vs those specific to the operation, and presenting as immediate, early or late complications. The incidence and nature of complications will be influenced by the patient’s comorbidities.

Immediate complications of a midline laparotomy incision may include anaesthetic difficulties, haemodynamic instability, primary haemorrhage from cut vessels and iatrogenic injury to surrounding tissues and viscera.

Generic early complications declare themselves in the hours and days following the operation and may include atelectasis, postoperative pneumonia, urinary tract infection, oliguria, bedsores and deep vein thromboses.

Specific early complications include reactionary haemorrhage where small vessels ooze and intra-operative haemostasis fails once the blood pressure normalises, intra-abdominal collection, postoperative ileus and wound infection. If nerves have been severed during the operation, this is most likely to become apparent over the following few days as the effects of anaesthesia wear off and the patient notices the deficit (or neuropathic pain).

Wound dehiscence following midline laparotomy is a particularly distressing event for the patient, whereby classically a serosanguinous discharge is noted from the wound 7-10 days postoperatively, and a day or so later the whole wound may burst open and spill the patient’s intestines into their lap.

Risk factors for wound dehiscence can be:

- Patient-specific (i.e. immunocompromised, smoking, obesity, jaundice, diabetes, steroid use, previous radiotherapy, vascular disease)

- Procedure-specific (i.e. surgical technique, site and orientation of incision, intra-operative contamination, lengthy procedure)

Late complications include the development of an incisional hernia, where the underlying peritoneum and associated contents protrude through residual defects in the abdominal wall, and the formation of dense fibrotic intra-abdominal band adhesions. Both of these conditions may result in lengths of bowel becoming trapped within the hernial sac (incarcerated), and the hernia may be sufficiently large or the defect through which it protrudes may be sufficiently tight to occlude intraluminal passage of bowel content (obstruction), venous outflow and later arterial supply (strangulation).

Illustrator

Aisha Ali

Medical Student and Illustrator