- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Table of Contents

Introduction

Ensuring patients’ wishes are respected and upheld is key when creating management plans and caring for patients.

Certain situations can make this more challenging, such as when mental capacity is lost. Advance care planning (ACP) is often used to preserve patients’ dignity and ensure their views are respected.

You may find that your hospital has a specialist ACP team to support you and your patients with advance care planning.

OSCE stations may examine students’ communication skills by assessing the ability to explain advance care plans in OSCE stations. You should approach the topic with empathy and focus on eliciting what is most important to your patient.

Advance care plans (ACPs)

Advance care plans (ACPs) describe the process of creating personalised documents which allow patients’ wishes about future medical intervention to be recorded, should they lose the ability to speak for themselves.

Advance care plans are created by having a person-centred discussion alongside a healthcare professional. They involve exploring the patient’s values and thoughts surrounding their health and exploring preferred future medical treatments. While the person has mental capacity, explaining the circumstances under which certain treatments may or may not work allows for shared decision making.

This could be relatively simple, for example, with the person stating which treatment they would not want, irrespective of circumstance. It could also be more intricate and dependent on other factors. Regardless, finding out your patient’s thoughts and feelings about this difficult topic will enable you to support them in creating an advance care plan they are happy with.

To ensure quality end-of-life treatment, multidisciplinary team members (MDT) should collaborate to create advance care plans. By planning for care provisions, these components can come together faster in the event of lost capacity and keep the patient comfortable.

Principles of advance care planning

NHS England has published universal principles of advance care planning:1

- Central to all conversations is the patient. This ownership extends to deciding who else is involved in decisions

- The needs and wishes of the person regarding their future care guide the topics

- Outcomes are agreed with the person and their health care professional

- The person has a record of the advance care plan stating their wishes and values, which they can share.

- The advance care plan is encouraged to be reviewed over time

- Should the advance care plan not be followed, anyone is able to freely speak up

Discussion points for ACPs

One of the key aims is ownership and control over the person’s future care. The exact content will vary from person to person depending on their unique situation, but generally, ACPs will typically include:2

- Advance decision to refuse treatment (ADRT)

- Do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DNACPR)

- Treatment escalation plans (TEP)

- Emergency care and treatment plans

- Lasting power of attorney (LPA)

Each of these areas will now be discussed in more detail.

Advance decisions to refuse treatment (ADRT)

Patients may express their wishes not to undergo specific treatments, which can be documented in an ADRT (also called an advanced decision or living will).

The ADRT must name every treatment that is not wanted. Where the decision to refuse or accept a treatment depends on the circumstances, this must be explicitly stated.

Healthcare professionals may provide information to aid the decision, but the statement is solely the patient’s. Therefore, it must be formally written down and signed by the patient and a witness.

Do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DNACPR)

Although a clinical decision, the person may wish to state their wishes not to be resuscitated should they enter cardiac or respiratory arrest. This decision is not legally binding but can guide clinicians to make the best decision for their patients.

The decision making process around resuscitation status is clinical and considers the patient’s comorbidities and functional status.

Responsible clinicians must consider the chances of success and the potential complications and harms of resuscitation (e.g., fractured ribs, internal bleeding). They must also consider the person’s dignity and whether further interventions, such as intensive care admission following resuscitation, would be appropriate.

Clinicians should communicate their decision to the person and document this. A section for discussion with family is stated on the DNACPR form. Thoughts from all persons involved should be recorded.

These discussions can be challenging and emotional for everyone involved. For more information, see our guide to DNACPR discussions.

Treatment escalation plans (TEP)

If the person’s health deteriorates, it is good practice to have a TEP form in place, clearly stating which investigations and treatment would or would not be appropriate. The aim is to reduce distress for the person and their family and ensure their wishes are upheld.

Treatment escalation plans can help decide how far treatment should be escalated. For example, whether artificial feeding via an NG tube or admission to hospital for intravenous antibiotics.

Emergency care and treatment plans

For patients with complex morbidity and long-standing illnesses, emergency care and treatment plans document what should happen if the person suddenly becomes unwell.

Such plans alleviate additional stress and allow those close to the person to be confident in their wishes being respected. For example, knowing if they would want invasive ventilation in the event of respiratory failure.

Lasting power of attorney (LPA)

A lasting power of attorney is a legal document that, in the context of health, allows the person to appoint a person or people to speak for them in the event that they become unable to do so for themselves. Decisions might include emergency treatment options or moving to residential care.

This information has the right to be private at the person’s discretion. When shared, for example, in hospital records and with their GP, there must be transparency about who has access. This extends to the person knowing they are able to review their records at any time.

Typically, the lasting power of attorney is someone who knows the person very well, such as a partner or close family member. They are accessed in the event the person becomes unable to speak for themselves or is deemed to have mental capacity.

The Office of the Public Guardian (OPG) oversees LPAs and supports those involved in performing their duties. An impartial party witnesses the signing of these documents at the time of creation.

There is also a lasting power of attorney for financial matters, which allows a nominated person, or people, to deal with the person’s finances. This does not require them to have lost capacity and is a separate form to the LPA for health.

Who might benefit from advance care planning?

While ACPs can be appropriate for any patient, they should be discussed with those who may lose their mental capacity or are at risk of their condition deteriorating. For example, patients with Alzheimer’s disease are more likely to lose cognitive function sooner than others.

Patients undergoing high risk procedures, such as major surgery, should be prepared for potential complications. Having an advance care plan is a responsible way to introduce conversations about associated risks and save time if the surgery does not go as planned.

People experiencing a deterioration in health are likely to benefit from having an up-to-date advance care plan. When accompanied by a person shifting from their home to residential care, such plans can ensure continuity.

If a person already lacks capacity, a best interests meeting may be held to facilitate advance care planning. If a lasting power of attorney has already been appointed, they can add valuable insight into the person’s wishes. In the absence of family or friends, an independent mental capacity advocate (IMCA) should be sought.

How to start discussions about advance care planning

If your patient introduces topics surrounding concerns over their future care or the eventuality of passing away, ACPs are likely to be a valuable asset in supporting them. Principally, the process must be voluntary and reflective of the patient’s wishes.

Such questions may look like:

- “What would happen to me if I can’t communicate my wishes anymore?”

- “What would happen to me if I don’t get better?”

Honesty is key to ensuring these conversations produce reliable and reflective outcomes of the person’s wishes.

You can use the following questions to initiate a conversation about ACPs:

- “What is most important to you about your care?”

- “Is there anything you do not want to happen in your care?”

- “Is there anyone you want to help deciding your care, should you be unable to answer?”

Trigger points to start discussions may be following a stay in hospital or an infection which negatively impacted their health. Empathy, in these instances, would be to explore the support available if this were to happen again, allowing the person the most control over their own health.

Illness trajectories vary from person to person. Someone in ill health may experience worse outcomes, and even a small infection might set their health back more so than another person. Advance care plans allow people to be realistic and prepared for poor outcomes.

There are plenty of resources to support, such as availability in a range of languages, cultural representation, advocacy, and peer support. Not everyone will be prepared or have considered their future care. These resources can assist in providing information in a range of circumstances.

Benefits of advance care planning

Benefits to the person

Advanced care planning supports the person’s ability to make decisions and feel a sense of control about their future care. It also has the advantage of opening up honest conversations and learning about what treatment options are available to them.

Benefits to the family

Those who are close to the person want to minimise any potential suffering. The families are able to be involved in decisions and express their thoughts, which might be very important to the person. These conversations allow difficult aspects to be raised and addressed and, hopefully, more quality time to be shared.

Stress is likely to also be decreased in the event the person falls unwell as well as they can have greater confidence that decisions made are what would be wanted.

Benefits for healthcare workers

Professionals often have to work to establish patients’ wishes, and in emergency situations this can be difficult. Advance care plans are clear, mitigating worry about what the person would want. The process of deciding on treatment is consequently sped up, and care (end of life or otherwise) is likely to be of better quality.

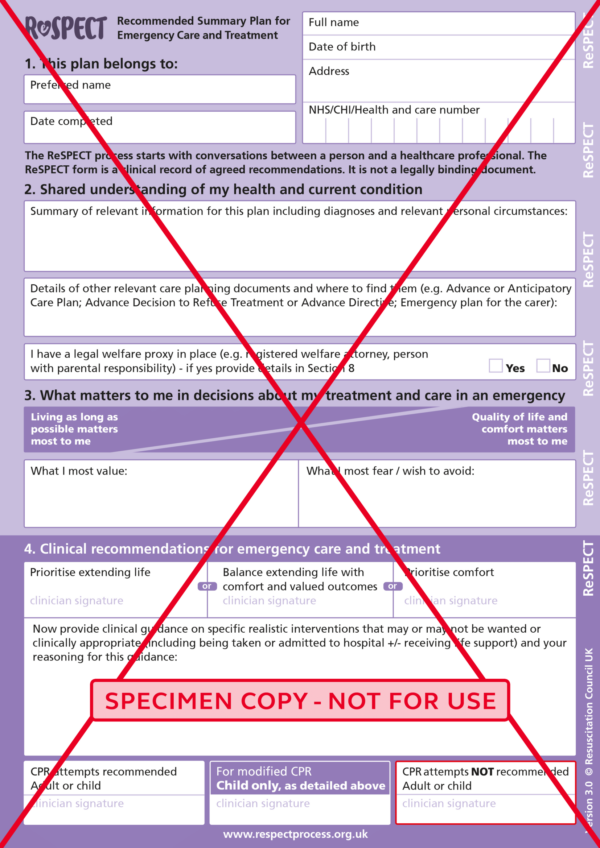

ReSPECT forms

A ReSPECT form is a preemptive plan stating a person’s wishes for emergency medical care should they be unable to express them.

ReSPECT stands for Recommended Summary Plan for Emergency Care and Treatment.

The purpose is to create a concise suggestion of what the person would want their care to consist of and any ceilings of treatment to avoid undue suffering. It is important to note that ReSPECT forms are not legally binding but allow family members and clinicians to act in the best interests of the patient.

Through conversations used to produce the ReSPECT form, patients and their families learn what is most important to the person and so enable clinical recommendations to be made. Any registered healthcare professional involved in the patient’s care may create a ReSPECT form with the patient. If necessary, these can be amended after creation, such as if health or preferences alter.

You should explain that, of course, even if a ReSPECT form is not created, healthcare workers will work to find out the patient’s wishes.

ReSPECT forms incorporate DNACPR decisions. Patients can use both forms, but ReSPECT will be used more going forward. 3

For more information on ReSPECT, see the Resuscitation Council website.

The ReSPECT form

Who are ReSPECT forms for?

While anyone may have a RESPECT form, they are mostly completed for those with significant or complex medical histories and where capacity may be absent in the near future.

Any patient likely to suffer a rapid deterioration in health might benefit from one. This could include those with chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes or cystic fibrosis.

Where patients are unlikely to recover from a non-remitting medical condition, ReSPECT forms are particularly important.

Cultural and religious considerations are also important. Remember that this may also be why someone would refuse treatment, such as an NG tube for artificial feeding.

They are not for requesting specific treatments without proper clinical indication.

Why have a ReSPECT form?

Some people may have had extensive experience with medical care previously and may not wish to repeat certain treatment paths.

In emergency scenarios, there may be limited time before decisions about treatment must be made. Having a ReSPECT form alleviates some of the stress and time required to find out the patient’s wishes.

Where consciousness is lost, this can be even harder to do. It is important to emphasise that emergency treatments can involve serious long-term consequences if successful and may not work. Furthermore, many treatments can be distressing and compromise dignity.

Others may want to alleviate the stress of families making difficult choices surrounding medical care. For example, ReSPECT forms provide confidence that their relative would not have wanted invasive ventilation.4

Key points

- Advance care planning (ACP) ensures patients’ wishes are respected and upheld, especially if they lose mental capacity

- ACP involves a person-centred discussion with a healthcare professional to document preferred future medical treatments

- Common components of ACP include Advance Decisions to Refuse Treatment (ADRT), Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (DNACPR) orders, and Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) for health

- ACPs are voluntary, not legally binding, and should be reviewed and updated regularly to reflect any changes in the patient’s wishes or circumstances

- Effective advance care planning can reduce stress for patients, families, and healthcare staff by providing clear guidance on the patient’s wishes for future care and treatment

Reviewer

Dr Arjun Kingdon

Palliative care consultant

Editor

Dr Jess Speller

References

- NHS England. Universal Principles for Advance Care Planning (ACP). Available from: [LINK]

- Marie Curie. Planning your care in advance. Available from: [LINK]

- Resuscitation Council UK. ReSPECT for healthcare professionals. Available from: [LINK]

- Resuscitation Council UK. ReSPECT for patients and carers. Available from: [LINK]