- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

A Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation order (DNACPR) is a document that formalises decision-making about whether an individual should be treated with CPR, in the event of a cardiac arrest.

It is a form of an advanced directive and is a key consideration in the management of patients with progressive life-limiting illnesses, those approaching the end of life, and significantly frail patients.

It is important to be familiar with the process of discussing a DNACPR with a patient, their family or carers, how to complete the form correctly, and how to document the decision.

This guide provides a step-by-step approach to conducting a DNACPR discussion in an OSCE setting. You should also read our overview of how to effectively communicate information to patients.

When is a DNACPR appropriate?

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) attempts to restart a person’s heart in the event of a cardiac arrest. It involves chest compressions, respiratory ventilation, defibrillation, and intravenous drugs.

It is an invasive process and has a low success rate as well as carrying risks such as rib fractures, and long-term adverse outcomes from prolonged resuscitation attempts, such as hypoxic brain injury. CPR is not appropriate for every patient who has a cardiac arrest.1

A DNACPR is appropriate in cases where it is likely the potential risks of CPR outweigh the potential benefits.

Data shows that for in-hospital cardiac arrests in the UK, less than 20% of patients survive to hospital discharge, across all demographics. The survival rate for elderly or frail patients is much lower. However, it is crucial to assess each patient on an individual basis and not discriminate based on these characteristics.1,2

The advantage of a DNACPR decision is that it can help to ensure a dignified death for patients.

DNACPR discussions often occur as part of end-of-life care, as a patient is reaching the final stages of their life. However, advance care planning such as DNACPRs should ideally be undertaken well in advance of a patient’s deterioration, to enable informed discussion with the patient and their family or carers.

DNACPR is an anticipatory decision and should be made in advance of when it is needed to be applied.

An important exception to a DNACPR is a cardiac arrest caused by an unanticipated and easily reversible cause such as choking or anaphylaxis.1 In these situations, it may be appropriate for resuscitation to be started. For example, if a patient with metastatic cancer has a DNACPR, but has a cardiac arrest, due to anaphylaxis from chemotherapy then full resuscitation measures may be appropriate.

Initiating a DNACPR discussion

There are no set criteria for when it is appropriate to initiate a discussion about resuscitation, and there is no single clinician who is responsible for this.

A discussion about DNACPR may be appropriate in a wide variety of contexts including:

- As part of advance care planning in the community with a well patient

- Whilst discussing treatment and prognosis with a patient with a chronic disease

- In an acute setting with a patient who is deteriorating

All clinicians involved in the patient’s care may be involved in these discussions.

Recognising the appropriate moment to initiate a conversation about resuscitation can be difficult. Patients may not have contemplated being unwell enough to die before meaning the discussion can be frightening. Some patients may not have realised the full implications of ill health, and the discussion may come as a shock, especially if in the context of a conversation around poor prognosis.

It is generally helpful to frame the discussion about resuscitation as part of a broader conversation about the patient’s care and treatment preferences. It is important to set aside sufficient time to do this.

It is crucial when explaining a DNACPR to be very clear on what it means, and that having this conversation does not necessarily mean that you expect the patient to decline rapidly.

These conversations should ideally be held in the presence of family or other individuals who are important to the patient. This also helps to ensure that the patient’s next of kin also understands why a DNACPR is appropriate and what it means. It is really important that everybody involved has the same understanding of future management.

Who to discuss a DNACPR with

In addition to the patient, a DNACPR should ideally be discussed with the patient’s family, next of kin, or carers. It may not be possible for them to be present at the discussion, but if so they should be informed of the decision at the nearest appropriate opportunity.

A DNACPR is a decision about medical treatment made by clinicians and therefore does not technically require patient consent.

However, the guidance states that resuscitation should be discussed with a patient or representative before the form is signed and that they should be informed of the decision. This is in line with the General Medical Council’s good medical practice.1,3

Furthermore, a Court of Appeal ruling on the Tracey case in 2014 established that patient distress or futility were no longer justifications for not discussing DNACPR with patients, emphasising that patients or a representative should always be informed of the decision unless there is a strong belief that physical or psychological harm would be caused.4

Explaining a DNACPR

Because signing a DNACPR does not require a patient’s or relative’s consent, it is important not to explicitly ask their permission to sign the form, as this gives a false understanding of how the decision is made.

There is no defined method by which a conversation about resuscitation should be had. The following can act as guidance for an appropriate way in which to structure the discussion.

Opening the consultation

Wash your hands and don PPE if appropriate.

Introduce yourself including your full name and role.

Confirm the patient’s or relative’s identity and what they would like to be called.

Explain the purpose of the conversation (i.e. that you wish to discuss resuscitation in the event of the patient deteriorating and having a cardiac arrest).

Gain consent and ensure the patient/relative is willing to have the conversation. They may find the topic distressing at first, at which point it may be more appropriate to come back at another time (depending on the urgency of the discussion).

Establish whether there is anybody else the patient/relative would like to have present for the conversation – if so, arrange for these people to be present, and return to finish the conversation.

Explore prior understanding

Explore the patient’s (or their relative’s) understanding of their current health state including the sequence of events leading up to this point

Introduce the concept of planning for the future

Explore their understanding of a DNACPR and resuscitation

Explaining cardiac arrests and resuscitation

Explain what is meant by a cardiac arrest: “As your illness progresses, you may become so unwell that your heart stops beating, this is called a cardiac arrest”.

Explain what is meant by CPR and what it involves including chest compressions, ventilation, defibrillation, and intravenous drugs. It is important to emphasise it is an invasive process (and to explain this in non-medical terms) with a low-success rate.

Explain what a DNACPR is, and why it is appropriate for this patient

Important information to convey includes:

- CPR is likely to be futile

- It is likely to lead to poor outcomes for the patient

Explain that a DNACPR means that in the event of a cardiac arrest, CPR would not be administered. It is important to emphasise it is specific to CPR as a treatment and does not apply to other interventions or treatments.

Patients may interpret a DNACPR as “giving up” on them. If a patient expresses this concern it is crucial to reassure them otherwise.

Explain that a DNACPR is a standard part of advance care planning. This helps the patient to understand that the discussion is a normal part of care, rather than something exceptional about their treatment.

Closing the consultation

Check the patient or relative’s understanding of the conversation.

Invite them to ask any further questions.

Summarise the conversation.

If the patient, next of kin or carers object to or disagree with the decision, you should listen to their concerns and attempt to address them through a further explanation. If they continue to disagree, the guidance from the GMC is to escalate to a senior clinician for a second opinion rather than continue to try to convince the patient otherwise.

Thank the patient for their time and check how they are feeling emotionally, as they may want to discuss the matter further with either yourself, another member of the team, or their family or carers.

Dispose of PPE appropriately and wash your hands.

Patients who do not have capacity

If the patient does not have capacity, this discussion should instead be had with their next of kin, or the person nominated to have decision-making power on their behalf (such as a medical Lasting Power of Attorney). The same principles apply, it is not this person who can make this decision, but the rationale for it should be fully explained to them.

If a representative for the patient is not available, then a DNACPR form can be completed without having had this discussion. The patient’s next of kin or a representative should be informed of the decision at the nearest available opportunity.

Completion of a DNACPR form

DNACPR forms may vary between hospitals. It is important to become familiar with the forms used in your local area.

A valid DNACPR form requires the following information:

- Personal details about the patient (i.e. name, date of birth, hospital and NHS numbers, home address)

- Contact details for the patient’s next of kin

- The reason why a DNACPR order is indicated. This is generally formatted as a list, with checkboxes used to indicate the most applicable scenario. These allow for all permutations of a DNACPR discussion – including where a patient does not have capacity, where a patient has declined to have the conversation or in a situation in which it would cause physical or psychological harm if the conversation were had.

- The details of the healthcare professional completing the form.

For a DNACPR order to be valid, then these details need to be completed in full.

Local procedures regarding who can sign the DNACPR form should be followed.

In some areas, doctors below registrar grade (but not FY1 doctors) may sign the form, but if so the form will only remain valid for 24 hours – and a counter-signature from a senior doctor is required to fully validate the form. The form may also be signed by a senior nurse depending on local procedures. The DNACPR decision must be endorsed by the most senior healthcare professional responsible for the patient’s care at the earliest opportunity.

Documentation and communication of a valid DNACPR decision

Documentation of a DNACPR decision

Once completed, a DNACPR form should be filed at the front of the notes in an inpatient hospital setting, or given to the patient or their carer to keep in a community setting. The patient should be advised to bring the form with them if they are admitted to hospital.

Signing a valid DNACPR form is the documentation of the discussion. However, it is good practice to contemporaneously document in the patient’s medical notes, a clinic letter, or GP record that this conversation has taken place and a form has been completed.

This documentation should indicate that the reasons for a DNACPR were explained to the patient and/or next of kin and that they understood the discussion. If the patient objected to the DNACPR, this should also be documented with any further action taken indicated.

Communication of a DNACPR to other medical professionals

It is also good practice to communicate a DNACPR decision to the other members of the team looking after that patient, in either an outpatient or inpatient setting. This ensures that the escalation planning for that patient if they were to deteriorate is understood by all members of the team looking after them. The patient’s GP should also be informed either via a letter (outpatient setting) or on the discharge letter (inpatient setting). Many hospitals indicate DNACPR status in their discharge summary templates.

DNACPR as part of advance care planning

Advance care planning refers to the process in which a patient, their family and carers, and healthcare professionals involved in their care agree and record the patient’s future preferences for care towards the end of life, especially if they lose capacity and would be unable to express these wishes.

Conversations about resuscitation and DNACPR are a part of this discussion, and other important aspects of advance care planning include preferred place of care or death, preferences about any future treatment, and formalised documents such as Advanced Decisions to Refuse Treatment (ADRT).

Recommended Summary Plan for Emergency Care and Treatment (ReSPECT)

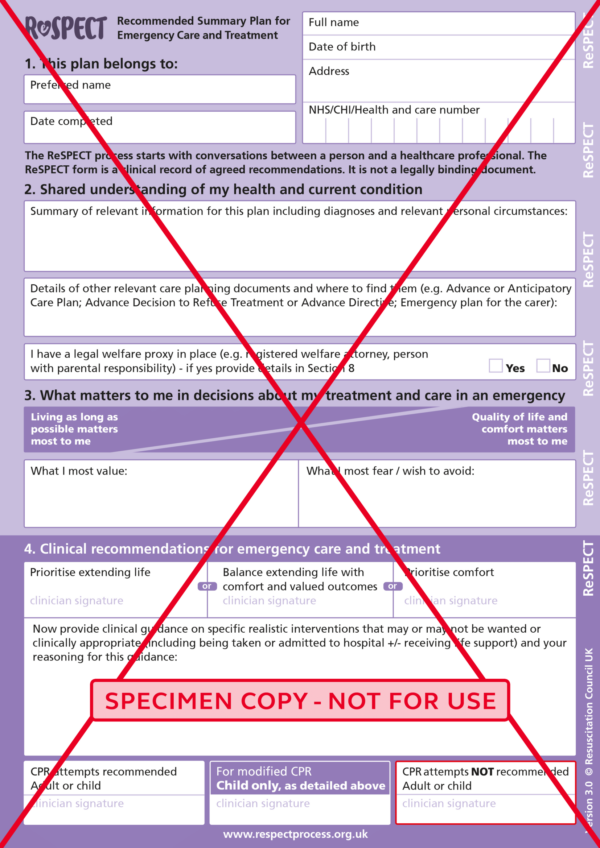

ReSPECT is a national process (in the United Kingdom) developed by the Resuscitation Council which creates personalised recommendations for a person’s care in a future emergency in which they are unable to make or express choices. It provides healthcare professionals with a summary of recommendations to help them to make decisions about that person’s care and treatment.

As part of the ReSPECT process, a decision regarding CPR is made and documented on the form. However, the ReSPECT process involves much more than just making a decision regarding CPR. For more information on ReSPECT, see the Resuscitation Council website.

Key points

- DNACPR decisions are a crucial aspect of advance care planning and end-of-life care.

- It is the responsibility of every clinician involved in a patient’s care to recognise when it is appropriate to make a decision about resuscitation, and it is an expected competency of a junior doctor to be able to have these discussions with patients and their families or next of kin.

- CPR is a medical treatment, and therefore the decision not to offer it is made by the medical team, rather than by a patient. Nonetheless, it is a key standard of care that these decisions are discussed with patients, to enable them to better understand the decision that has been taken.

- A DNACPR decision applies only to CPR and not to any other forms of treatment.

- Once a DNACPR order is completed, it needs to be communicated to other professionals involved in a patient’s care, and clearly documented in the patient’s medical notes.

- Conversations about resuscitation can be difficult and distressing for patients and their families, but with advanced planning and good communication, this can still be a positive process in many cases.

- Appropriate DNACPR decision-making can help to ensure dignified deaths for patients and cause less distress at the end of life.

Reviewer

Dr Vanessa Wilshaw

Consultant in Clinical Oncology

References

- The British Medical Association, the Resuscitation Council (UK) and the Royal College of Nursing. Decisions relating to cardiopulmonary resuscitation. 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- Nolan, J.P. et al. Increasing survival after admission to UK critical care units following cardiopulmonary resuscitation. 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- General Medical Council. Good medical practice. 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Etheridge, Z. and Garland, E. When and how to discuss “do not resuscitate” decisions with patients. Available from: [LINK]

- The Resuscitation Council (UK). ReSPECT for healthcare professionals. 2020. Available from: [LINK]