- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

All patients having an operation under general or regional anaesthetic require a pre-operative assessment (POA). This should identify any medical comorbidities and optimise the patient’s physiological state to minimise the impact of surgical procedures and anaesthetic. It is also an opportunity to recognise patients at higher risk of complications that would benefit from additional post-operative care.

This article aims to provide an overview of anaesthetic pre-operative assessment which may be useful for OSCE scenarios and hospital placements. The information in this guide is not to be used in the management of actual patients.

Aims of anaesthetic pre-operative assessment

The anaesthetic POA is often the first-time patients will meet their anaesthetist. It is an opportunity to start building a rapport with patients and ensure the patient is fully informed about the procedure and associated health implications. The assessment involves information gathering in the form of a focussed history and examination, and information sharing to involve the patient in decisions regarding their care.

For the majority of patients, a full medical clerking is not always necessary and the emphasis is on airway and cardiorespiratory assessment. Once a patient is under general anaesthetic, they will be unable to support their own airway. The POA should highlight potential difficulties in securing airway so appropriate measures can be put in place before the patient is anaesthetised.

Anaesthesia can have a significant impact on a person’s physiology, particularly on their ventilation and perfusion. A cardiorespiratory assessment must identify any pre-existing disease (e.g. myocardial infarction, cardiac murmur, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), along with the patient’s baseline level of function. This status assessment is balanced against the metabolic demands of surgery and anaesthetic to ensure patients are adequately monitored and receive appropriate organ support during and after the operation.

Patients admitted with an acute condition or requiring emergency surgery, will not have the same amount of time available for optimisation. In this scenario, the anaesthetist will use the POA to make a decision about the level of risk involved in operating immediately (versus postponing the procedure to enable optimisation or resuscitation). This is a dynamic, multidisciplinary process and it is essential that the patient and their family understand the risks involved so they can make an informed decision.

Scoring systems

The perioperative period refers to the time in the patient’s journey encompassing pre-operative assessment, anaesthesia, surgery and postoperative recovery. Scoring systems are used to risk-stratify patients requiring surgery and identify those at higher risk of complications who could benefit from increased support in the perioperative period. The American Society of Anaesthetist (ASA) Scoring System is used routinely as part of the WHO Safer Surgery Checklist. Other scoring systems are useful to quantify risk in patients requiring non-elective surgery.

American Society of Anaesthetist (ASA) score:

- Normal healthy patient

- Mild systemic disease (e.g. asthma)

- Severe systemic disease

- Severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life

- Moribund patient, not expected to survive without the operation

- Declared brain-dead patient – organ removal for donor purposes

Surgical severity score:

- Grade 1 – diagnostic endoscopy, laparoscopy, breast biopsy

- Grade 2 – inguinal hernia, varicose veins, adenotonsillectomy, knee arthroscopy

- Grade 3 – total abdominal hysterectomy, TURP, thyroidectomy

- Grade 4 – total joint replacement, artery reconstruction, colonic resection, neck dissection

Other risk assessment scoring tools:

- NELA – National Emergency Laparotomy Audit

- SORT – Surgical Outcome Risk Tool

- POSSUM – Physiological and Operative Severity Score for the enumeration of Mortality and Morbidity

Structured assessment

Overall, the POA is very similar to a medical or surgical admission clerking, with a few important questions relating specifically to anaesthetics. There is a lot of detail, not all of which will be relevant to every patient. Use the summary at the end of this tutorial, or pick out the relevant sections below.

Generally, the assessment should take 5-10 minutes for healthy patients requiring elective procedures. For emergency operations, or patients requiring more severe surgical interventions, it will take longer to collect relevant information and make an appropriate risk/benefit decision. Other sources of information include a patient’s next of kin, inpatient notes, outpatient clinic letters and GP records.

Everyone does this differently and it’s important you develop a structure that works for you.

Previous anaesthetics

Key questions to ask about previous anaesthetics include:

- Has the patient had any previous anaesthetics? If so, was that under general anaesthetic or another method? – e.g. peripheral nerve blocks, spinal, epidural and/or sedation

- Did they have any problems with previous anaesthetics?

- Serious anaesthetic complications:

- Malignant hyperthermia (MH) – a rare reaction to volatile anaesthetic agents and neuromuscular blocking drugs that can cause dangerously high body temperature and muscle contractions

- Suxamethonium apnoea – a deficiency in enzymes required to break down suxamethonium, resulting in prolonged paralysis of skeletal muscle

- Anaphylaxis. See the Geeky Medics guide for clinical features of anaphylaxis.

- Difficult airway

- Sometimes patients are not sure, or will say something like “Oh I was slow to wake up”. In this case, it’s important to determine how seriously they were affected. Some questions to help you include:

- How long did they take to wake up? Was it a few hours or a few days?

- Did they require intensive treatment unit (ITU) admission post-op due to problems waking up?

- Is there any family history of problems with anaesthetics?

- Have they or their family members had any specific testing? – i.e. genetic, allergy or other testing relating to anaesthetic agents (MH or suxamethonium apnoea)

- Did they experience postoperative nausea and vomiting previously?

- If you’re unsure about anything relating the patient’s past anaesthetic history, ask a senior and/or contact the anaesthetist.

Allergies and intolerances

There is a difference between allergies and intolerances but patients won’t always be able to tell you. It is therefore important to ask what kind of reaction they had to each medication.

Did they have a rash/swelling/anaphylaxis? Or was it nausea/diarrhoea after taking an oral medication?

Key information to gather:

- List all allergies and intolerances, regardless of the severity

- Ask specifically about penicillin

- Ask specifically about NSAIDs

Medication history

Often when asked about past medical history, patients will say something like “Oh yes, I’m very healthy” and then will go on to give a long list of medications. You may find it easier to start with this section to get an idea of what you might need to ask about in more detail later.

Ask specifically about anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents, antihypertensives and when they last took them.

Ask about any analgesics and when they last took them.

Ask about “over the counter” and herbal medications.

Presenting complaint

What led them to want/need this operation? It may be useful to start with this when assessing inpatient admissions or patients requiring emergency surgery.

Certain operations will require you to ask for more information as the patient’s presenting complaint may affect decisions regarding the anaesthetic plan. Specialist surgery (e.g. Cardiothoracics, Neurosurgery, Paediatrics, Obstetrics) will have more specific questions that you should contact the surgical or anaesthetic team about. Some examples include:

- Maxillofacial surgery – mouth opening, swelling, dental problems

- Ear, Nose and Throat surgery – snoring/sleep apnoea, hypertension (some operations require induced hypotension to reduce bleeding and improve the surgeon’s visual field)

- GI surgery – reflux/nausea/vomiting/features suggesting bowel obstruction, anaemia

- Gynae surgery – nausea/reflux, anaemia

Past medical history

You know how to take a medical history, but below is some advice on specific information an anaesthetist would want to know.

Key questions:

- Who manages their chronic condition?

- Recent GP visits and hospital admissions relating to a chronic condition

- Recent changes in treatment

- Associated complications of condition and body systems affected

Tip: with chronic conditions its useful to ask more questions to gauge their severity.

Respiratory

Asthma/COPD:

- Regular medications, compliance and degree of control

- Recent oral steroid treatment

- Exacerbating factors

- Smoking status

Obstructive sleep apnoea:

- Diagnosed or under investigation

- BMI

- Observed apnoeic episodes

- Daytime somnolence

- Do they use a CPAP mask at night?

Functional status:

- Exercise tolerance

- Able to lie flat without becoming breathless?

Other:

- Recent hospital or ITU admissions

- Recent cough/cold or features suggesting current acute illness

Cardiovascular

Hypertension:

- How is this managed and by who?

- Do they know what is normal for them at home?

- Is there evidence of end-organ damage? – e.g. reduced renal function

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS):

- Previous myocardial infarction? When? Symptoms? What treatment?

- Have they had angiogram/PCI/CABG and what vessels were implicated?

- Recent ECHO?

- See Table 1 for guidelines on grading cardiovascular disease

Heart failure:

- Exercise tolerance

- Breathless when lying flat? (this is important as they will probably need to lie flat for their operation)

- Peripheral oedema

Valve disease:

- Syncopal episodes

- Surgical treatment

Atrial fibrillation:

- Anticoagulation

- Associated complications

Table 1. Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (AAGBI) Guidelines on grading the severity of cardiovascular disease

| MILD CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE | SEVERE CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE |

| Mild angina, not limiting ordinary activity | Severe/unstable angina limiting activity |

| MI > 1 month ago | MI < 1 month ago |

| Compensated heart failure | Decompensated heart failure |

| Severe valvular disease |

Diabetes

Key questions to ask about diabetes:

- How is it controlled? Diet, oral medication or insulin?

- How often do they check their capillary blood glucose and what’s normal for them?

- Do they still have hypo-awareness?

Renal

Key questions to ask about renal disease:

- Type of renal disease and cause (if known)

- Fluid restriction

- Dialysis schedule

Neurological

Key questions to ask about neurological disease:

- Previous stroke or TIA?

- Residual symptoms – specifically swallowing, communication, mobility

- Epilepsy – seizure type, most recent seizure, medication

- Dementia/delirium – exacerbating factors, alleviating factors (e.g. family presence)

Gastrointestinal

Gastro-oesophageal reflux (GORD):

- A history of GORD can potentially affect how the patient’s airway is managed. Significant reflux would require rapid sequence induction and intubation to reduce the risk of stomach contents contaminating the airway.

- Triggers – e.g. food, lying supine

- Associated symptoms – discomfort, acid into throat/mouth

- Frequency and the most recent episode

- How is it controlled?

Nausea and vomiting

Alcohol use:

- Quantify amount

- Features suggesting dependence and risk of withdrawal

Musculoskeletal

Conditions affecting the cervical spine as this may make airway access difficult:

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Osteoarthritis

General mobility and assistance with walking/self-care as this will guide post-operative recovery requirements

Gynaecological

For women of reproductive age, could they be pregnant?

When was their last menstrual period?

Fasting period

Fasting periods are essential to ensure the patient has an empty stomach before they undergo an anaesthetic. This is to minimise the risk of aspiration of stomach contents.

Fasting periods:

- WATER – up to 2 hours before induction of anaesthetic

- FOOD/MILK-CONTAINING DRINKS – up to 6 hours before induction of anaesthetic

- ***Chewing gum up to 2 hours before induction ***

Airway assessment

There are many methods used to assess patients’ airways. The aim of these assessments is to predict possible difficulties in securing the airway once a patient is asleep. There is no definitive test that will absolutely identify whether a patient will have a difficult airway, but the more features present in one patient, the greater the risk of airway problems on induction. Some of the assessment tools used by anaesthetists are shown below.

Wilson’s score

Wilson’s score (Table 2) lists different methods of assessing the airway, but the actual scoring system is not frequently used:

- Score <5 suggests easy laryngoscopy

- Score 5-8 suggests potentially difficult laryngoscopy

- Score 8-10 indicates a risk of severe difficulty in laryngoscopy

* For an explanation of laryngoscopy, see the Geeky Medics guide here.

Table 2b. Wilson’s score for predicting difficult laryngoscopy

| Feature | Score |

| Weight |

0 <90kg 1 >90kg 2 >110kg |

| Head and neck movement |

0 = Neck extension >90 degrees 1 = Neck extension = 90 degrees 2 = Neck extension <90 degrees |

| Jaw movement |

0 ICG >5cm or JP >0 1 ICG <5cm and JP = 0 2 ICG <5cm and JP <0 ICG = interincisor gap when mouth fully open JP = Forward protrusion of lower incisors beyond upper incisors |

| Receding mandible |

0 = Normal 1 = Moderate 2= Severe |

| Buck teeth |

0 = Normal 1 = Moderate 2 = Severe |

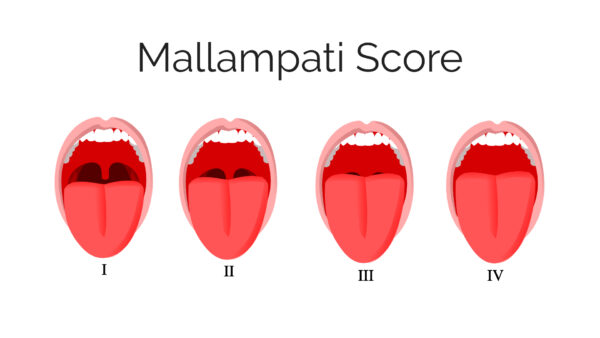

Mallampati score (Figure 1)

The Mallampati score is used to predict the ease of endotracheal intubation. The test comprises a visual assessment of the distance from the tongue base to the roof of the mouth, and therefore the amount of space in which there is to work.

Dentition

Ask about any caps or crowns a patient might have and whether they have any loose or wobbly teeth.

Poor dentition can make accessing an airway more difficult.

Medications and surgery

Patients will be advised that they can take most of their normal medications before their elective operation. However, some medications should be omitted or altered pre-operatively and this section will provide some detail on those. It is not exhaustive, so for further advice, you should review local trust guidelines or guidelines published by AAGBI or Royal College of Anaesthetists.

Anticoagulants2

Anticoagulants work by inhibiting various clotting factors and have variable durations of action. Patients will be less able to form clots and therefore more likely to bleed during a surgical procedure. Additionally, there are strict timeframes that govern when a neuraxial block (spinal, epidural) can be performed after administration of anticoagulant or antiplatelet medications. These will change depending on patient factors such as BMI and renal function, so always check local guidelines before stopping anticoagulant medications.

Warfarin

For minor superficial surgery (e.g. ophthalmic or minor dental procedures) warfarin may not need to be omitted (however guidelines vary, so always consult local guidance).

For all other surgical interventions, the last dose of warfarin should be given 6 days before the procedure.

For emergency surgery or surgery where warfarin was not omitted, check INR and consider reversal with Vitamin K or other agents according to procedure and timeframe. This needs to be discussed with the surgical and anaesthetic team involved in the case.

“Bridging therapies” refers to the use of alternative anticoagulation therapy, such as short-acting low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), during the pre- and immediately postoperative period. Your hospital trust will have a protocol on this.

Heparin

Unfractionated heparin is short-acting and normally given via IV infusion. It must be stopped 4 hours before neuraxial block with evidence of a normal APTT.

LMWH is longer acting and administered subcutaneously. Following “prophylactic dose LMWH”, a neuraxial block cannot be performed for 12 hours. Following “treatment dose LMWH”, this is increased to 24 hours.

Novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs)

Rivaroxaban clearance is dependent on dose and renal function:

- Prophylactic dose with creatinine clearance >30ml/min – 18 hours before neuraxial block.

- Treatment dose with creatinine clearance >30ml/min – 48 hours before neuraxial block

Dabigatran – wait 48 hours before neuraxial block

Apixaban – wait 48 hours before neuraxial block

Antiplatelets

Aspirin, dipyridamole and NSAIDs can be continued as per patient’s usual prescription unless there are confounding factors such as deteriorating renal function.

Clopidogrel causes irreversible platelet inhibition and therefore should be stopped 7 days before surgery and/or neuraxial intervention.

Antihypertensives and antiarrhythmics

Angiotensinogen converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors should be withheld on the morning of major surgery. If unsure, contact the anaesthetic team.

Beta-blockers should be continued as per the patient’s normal prescription unless otherwise instructed.

Patients on digoxin will need an ECG and blood tests to exclude hypokalaemia.

Anticonvulsants

Patients should continue their normal anticonvulsant therapies unless otherwise indicated.

Diabetic medications

Oral hypoglycaemic agents such as metformin should be omitted on the day of surgery. It is important the surgical and anaesthetic teams are aware of diabetic patients listed for surgery as they will need to be first on the operative list to minimise the starvation period.

Diabetic patients that will be missing more than one meal due to fasting and operative time should be considered for insulin-dextrose sliding scale therapy during the perioperative period.

Steroids

Patients who take more than 5mg prednisolone daily will need supplementary steroids during the perioperative period.

Dose and duration are dependent on normal steroid regimen and severity of the surgery. See BNF guidelines for more information.

The anaesthetist should be made aware of patients requiring additional peri-operative steroid treatment.

Hormonal therapies

The oral contraceptive pill (OCP) can increase the risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in patients who will be immobile post-op. The OCP should, therefore, be stopped in this patient group, or if not possible, additional measures to ensure adequate venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis should be considered. The same is true of some hormone replacement therapies.

Tamoxifen is used in the management of breast cancer and should only be stopped if the risk of VTE outweighs the risk of interrupting treatment.

Antidepressants

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOi) can have dangerous interactions with certain anaesthetic drugs. If a patient is on a MAOi, it is essential that the anaesthetist responsible for the patient at the time of surgery is informed.

Patients taking lithium should have a lithium level and U&Es checked, along with TFTs before proceeding to surgery.

Herbal medications

Herbal medications such as St John’s Wort and ephedra should be stopped 2 weeks before surgery.

Pre-operative medications

Often an anaesthetist will choose to give patients a pre-op medication on the morning of their surgery. This will work during the operation and into the postoperative period. Do not prescribe pre-operative medications for patients unless asked to do so by the anaesthetist. Common pre-op medications are shown below.

Analgesics

Paracetamol and codeine are given for their analgesic effects during surgery.

NSAIDs are given if there are no patient or surgical contraindications.

Antacids

Ranitidine or omeprazole can be given to minimise stomach acid and reduce the risk of aspiration during induction.

Anxiolytics

Anxious patients, or patients requiring procedures pre-operatively such as peripheral nerve blocks or invasive line insertions, can be given anxiolytic medications such as midazolam. This is done at the discretion of the anaesthetist.

Anti-sialagogue

Occasionally patients will be given medication such as glycopyrrolate to reduce oral secretions prior to airway instrumentation.

Additional investigations

Patients listed for elective surgery may require optimisation in the pre-operative period to ensure they are fit enough to undergo their operation. This may include investigations such as blood tests, chest X-ray (CXR), ECG or echocardiogram (ECHO). Your trust will have guidelines on what is required for specific operations and the POA you have performed should indicate any additional tests required.

NICE Guidelines recommend the pre-operative investigations discussed below.3

ECG

An ECG should be performed in the following circumstances:

- >80 y/o

- >60y/o and surgical severity >3

- Cardiovascular or renal disease

Blood tests

FBC:

- If > 60y/o and surgical severity >2

- All adults with surgical severity >3

- Severe renal disease

U&Es and creatinine:

- > 60y/o and surgical severity >3

- All adults with surgical severity >4

- Renal disease

- Severe cardiovascular disease

Sickle cell test:

- Families with homozygous disease or heterozygous trait

Pregnancy test

Should be performed in all women of reproductive age.

Baseline CXR

Should be performed for all patients scheduled for post-op critical care admission.

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET)

CPET is useful for assessing cardiovascular and respiratory functional capacity.

It will be requested by the anaesthetic or surgical team for patients with chronic disease affecting their daily function who are listed for major surgery.

Hypertension4

This can be difficult to assess on the day of surgery as pre-op nerves can raise blood pressure. If a patient’s BP is greater than 180mmHg systolic or 110mmHg diastolic on the day of surgery, the operation should be postponed until hypertension is under control. Inform the GP as BP management should be done in partnership with primary care. The patient’s BP needs to be 160/100 mmHg or lower in the community prior to the operation.

Anaemia3

Anaemia (Hb <13g/dL in men AND women) necessitates further investigation. An anaemic patient requires investigation and optimisation before surgery to avoid peri-operative blood transfusion. Your trust should have guidelines on investigation and management of anaemia, but thorough history, examination and haematinics are a good place to start. Inform the patient’s GP and ensure they are involved in any further investigations and treatment decisions.

Referral for anaesthetic review

Every hospital will have an anaesthetic POA clinic. This allows the patient and their family to meet with a member of the anaesthetic team to discuss the operation and anaesthetic they require. During this meeting, the anaesthetist will take a history, make a risk/benefit assessment and organise any further investigations or treatment required to optimise the patient’s pre-op condition. The patient and their family will be involved in deciding what the best and safest options are for their surgery and anaesthetic.

There is usually a referral pathway in local trust with guidelines on how to refer a patient to the anaesthetic clinic. You may also be asked to organise additional investigations such as blood tests, ECG and ECHO. If you’re not sure whether a patient will require a review, speak to a senior or ask the anaesthetist responsible for the patient’s surgical list.

Summary

Assessment

Background

Previous anaesthetic history:

- When did they have an anaesthetic and what for?

- Previous problems with anaesthetics problems (malignant hyperthermia, suxamethonium apnoea, anaphylaxis, postoperative nausea and vomiting)

- Family history of anaesthetic problems

Allergies:

- What drug?

- What type of reaction?

Regular medications:

- What drug?

- When was their last dose?

- Anticoagulants, antiplatelets

Presenting complaint:

- What led them to want/need this surgery?

Past medical history:

- Respiratory assessment

- Cardiovascular assessment

- Reflux assessment

- Functional assessment

Airway assessment

The following should be assessed:

- Mouth opening

- Jaw protrusion

- Neck movement

- Mallampati score

- Dentition

Preparation

Fasting period:

- 6hrs – food/milk

- 2 hrs – water

Peri-operative medications:

- Make a plan for their regular medications – do any need omitting or altering?

Further investigation:

- Does the patient require further investigations or treatment before their surgery (e.g. due to anaemia, hypertension or acute change in their clinical condition)?

- Does the patient meet the criteria for referral to the pre-operative anaesthetic assessment clinic?

Consent:

- Ensure the patient has consented appropriately for their operation AND anaesthetic.

Senior advice:

- Anything you’re unsure about should be discussed with a senior or with anaesthetist responsible for the surgical list.

References

- Jmarchn. Mallampati Score. [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Britain G, The I, Anaesthetists O. Regional Anaesthesia and Patients with Abnormalities of Coagulation. 2013;(November):1–14.

- O’Neill F, Carter E, Pink N, Smith I. Routine pre-operative tests for elective surgery: Summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2016;354(April 2016).

- AAGBI, Hartle A, McCormack T, Carlisle J, Anderson S, Pichel A, et al. Measurement of adult blood pressure and management of hypertension before elective surgery 2016. Anaesthesia [Internet]. 2016;71(March):326–37. Available from: [LINK]