- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

This article will discuss the anatomy of the abdominal wall and rectus sheath. You may be interested in our other abdominal anatomy articles.

The abdominal wall

The lateral abdominal walls are formed by a triad of muscles:

- the external oblique (E.O), with its fibres running inferomedially like the fingers of the hands placed into the front pockets of one’s jeans

- the internal oblique (I.O) with its fibres running orthogonally to its external relation

- transversus abdominis (T.A) with its horizontal fibres.

Superficial to the external oblique lies Scarpa’s membranous fascia, Camper’s subcutaneous fatty layer, and the skin. Deep to transversus abdominis, the transversalis fascia encircles the preperitoneal fat and parietal peritoneum.

Incisions through the anterolateral abdominal wall will, therefore, breach the following structures:

- Skin

- Subcutaneous fatty layer

- Membranous fascia

- External oblique

- Internal oblique

- Transversus abdominis

- Transversalis fascia

- Preperitoneal fat

- Parietal peritoneum

As the fibres of the lateral abdominal wall muscles progress medially they give rise to fibrous sheets of tissue known as aponeuroses, allowing a far wider area of insertion than would be achievable with the typically round tendons seen on muscles of the appendicular skeleton.

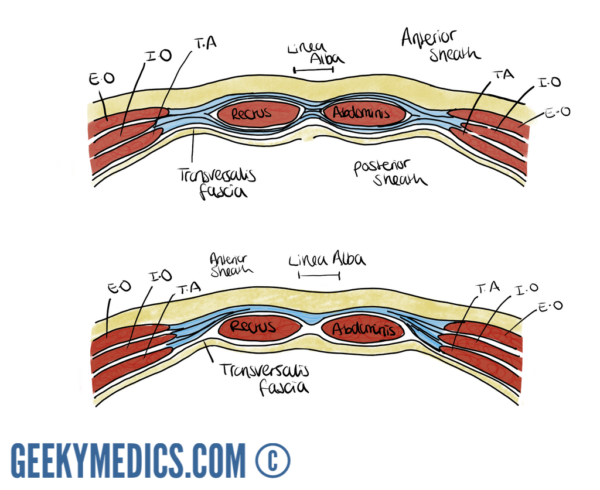

The internal oblique is unique in that its aponeurosis divides into an anterior and posterior leaf, the relevance of which will become clear later. These aponeuroses combine and interdigitate in such a way as to invest the paired longitudinal rectus abdominis muscles, forming the anterior midline structure known as the rectus sheath.

The rectus sheath

The paired rectus abdominis muscles originate from the anterior bony pubic bones toward the midline and run cephalad to insert onto the xiphisternum and costal cartilages of ribs 5-7.

They derive their blood supply from the superior and inferior epigastric arteries from the internal thoracic and external iliac arteries respectively, and their innervation from the anterior rami of spinal nerve roots T7-T12.

The rectus sheath may be considered as having three distinct sections:

1. For most of the length of the paired recti, the anterior sheath is formed by the external oblique and anterior leaf of the internal oblique aponeuroses. The recti are interrupted by three paired tendinous intersections anchoring them to the anterior sheath, broadly found close to the xiphisternum, at the level of the umbilicus and then halfway between the two.

The posterior sheath is formed by the posterior leaf of the internal and the transversus abdominis aponeuroses and bears the superior and inferior epigastric arteries and their anastomotic network. The aponeurotic components of the sheath interdigitate in a thickened fibrous midline raphe between the two recti known helpfully as the linea alba (‘white line’). An elastic defect in this raphe may allow the fascia to stretch and abdominal contents to bulge forward through the resulting divarication of the recti. This produces a distinct ridge in the midline on increasing intra-abdominal pressure that is often mistaken for an epigastric hernia.

Point defects in the aponeurotic intersections of the linea alba may facilitate the development of epigastric hernias, which often simply contain preperitoneal fat but are often disproportionately painful for their size owing to their high tendency to strangulate.

2. There is no posterior sheath above the level of the costal margin, as the recti remain covered anteriorly by the external oblique aponeurosis and insert directly onto the underlying costal cartilages.

3. Roughly one-third to halfway between the umbilicus and the pubic symphysis lies the arcuate line (of Douglas), which is the point at which the posterior elements of the sheath perforate to join the anterior sheath and leave the thickened transversalis fascia in direct contact with the rectus muscles. The sheath is bounded laterally by the linea semilunaris, which is the longitudinal margin at which the internal oblique aponeuroses bifurcate to form anterior and posterior leaves.

Defects in the integrity of the internal oblique may give rise to the formation of Spigellian hernias, allowing protrusion of the peritoneal sac into the rectus sheath. On examination, the patient may have a palpable lump close to the lateral border of the rectus sheath, commonly at the level of Douglas. The superficial nature of these hernias makes them amenable to diagnosis by ultrasonography.