- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Table of Contents

Introduction

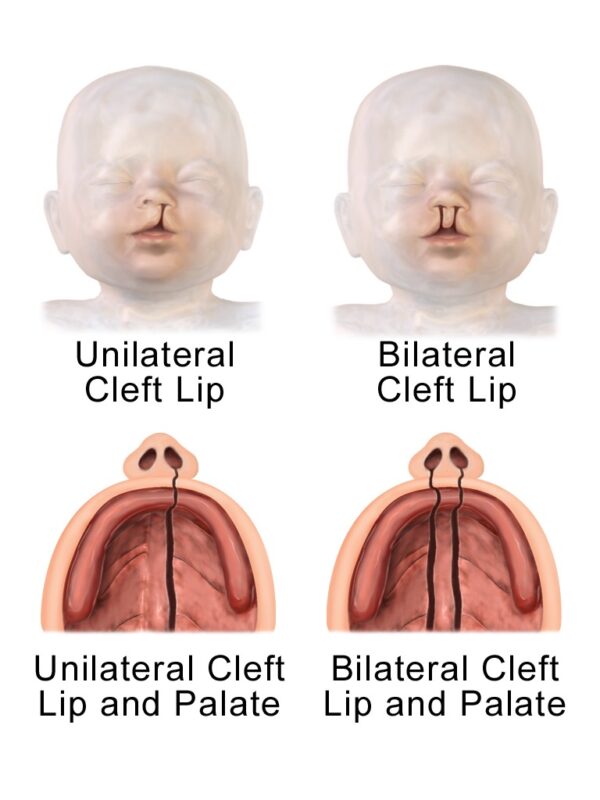

A cleft forms when the failure of normal lip and/or palate development leaves a gap or channel in the lip and/or palate. The severity can range from an isolated unilateral cleft lip or palate to having a bilateral cleft lip and palate.1

A cleft lip and/or palate affects 1 in 700 babies born in the UK, making it the commonest craniofacial difference. This means that around 1200 babies are born every year with a cleft in the UK.

Of these babies, 31% will have a cleft lip and palate, 45% will have an isolated cleft palate and 24% will have an isolated cleft lip. Only 8% of babies born with a cleft in the UK have a bilateral cleft lip and palate.1

This article will provide information on cleft lip and palate, how they form, as well as the risk factors and common genetic syndromes associated with a cleft. It will also provide an overview of treatment and what the typical long-term management pathway for a patient with a cleft may look like.

Aetiology

A patient may have an isolated cleft lip or palate, or a combination of both.

A cleft lip forms when the nasal prominences and maxillary prominences fail to properly fuse and create the lip during weeks 5 to 6 of embryological development. This creates a unilateral or bilateral cleft lip depending on if the failure of fusion occurs on one side or both.2

The severity of the cleft can range from a little notch in the lip to complete separation of the lip and gum running up to the nose.1

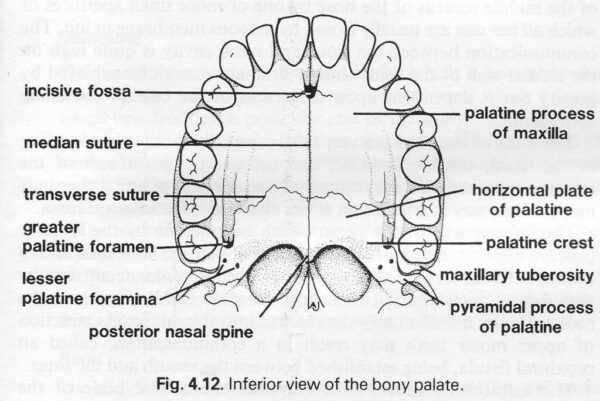

The primary and secondary palates then develop during weeks 5 to 12:2,3

- The primary palate consists of a triangular area of the hard palate anterior to the incisive foramen and a portion of the alveolar ridge. It is created by the medial nasal prominences fusing at the midline.

- The secondary palate consists of the remaining hard palate and the soft palate. It is created by the lateral palatine processes fusing at the midline from anterior to posterior.

A cleft palate forms when either of these processes fails and can result in a unilateral or bilateral cleft. A partial palatal cleft only affects the soft palate while a complete cleft affects the hard and soft palates.6

Cleft palates may also be submucous meaning that the overlying mucosa is intact while the underlying palate muscles have failed to fuse at the midline.3 7

Risk factors

The cause of clefts among most babies is unknown. It is widely agreed that clefts usually arise from a combination of genetic and environmental factors during pregnancy. They may also arise due to a genetic syndrome.1

Risk factors which increase the risk of a baby being born with a cleft include:8

- Family history of cleft

- Smoking or alcohol use during pregnancy

- Obesity during pregnancy

- Low folic acid during pregnancy

- Taking epilepsy medications such as topiramate or sodium valproate during the first trimester.9

Around 15% of clefts arise secondary to a genetic syndrome, where a genetic mutation results in a wide range of birth defects.10 Some of these conditions include 22q11.2 microdeletion syndrome (DiGeorge), Pierre-Robin sequence and Treacher-Collins syndrome.7,8

Clinical features

A cleft lip is usually diagnosed during the anomaly ultrasound scan during weeks 18-21 of pregnancy.

If it is not diagnosed then, it should be picked up immediately after birth or during the newborn physical examination (NIPE) within 72 hours of birth. This examination includes direct visualisation of the hard and soft palate using a torch and a tongue depressor.11

When a cleft lip or palate is diagnosed, the family is immediately referred to a specialist multidisciplinary cleft team and seen by a cleft specialist nurse within 24 hours.8

An untreated cleft lip or palate can cause several problems:8

- Airway problems: especially in children with Pierre-Robin Sequence, which presents with a triad of a small jaw (micrognathia), a floppy tongue that falls back into the mouth (glossoptosis) and airway problems. Pierre-Robin is also associated with a cleft palate in 90% of cases. Such babies may need to be positioned on their side or front to allow the tongue to fall forwards and prevent it from obstructing the airway. Further treatment options include the use of a nasopharyngeal airway, a tongue-lip adhesion surgery, or a tracheostomy.

- Feeding problems: a baby with a cleft lip or palate may struggle to create a good seal around the nipple or teat of a normal baby bottle. This may result in fatigue, poor weight gain, excessive air intake, choking and nasal regurgitation. A special feeding bottle and advice from the cleft specialist nurse are essential.

- Glue ear and associated conductive hearing loss: as many as 90% of patients with an unrepaired cleft palate have glue ear secondary to eustachian tube dysfunction.7

- Psychosocial impact: a cleft may lead to low self-confidence, depression, and anxiety. The child may also be a target for bullying or discrimination.

- Dental problems: an untreated cleft can mean a child’s teeth do not develop correctly resulting in misaligned teeth and future dental problems.

- Speech problems: a cleft palate can lead to a hypernasal voice and unclear speech as the child grows up.

Management

Initial management

A specialist cleft nurse will visit within 24-48 hours of birth to provide information and support. The first few months after diagnosis involve giving the family support and information on the diagnosis and ensuring that the baby grows adequately to allow future surgery.

Initial management requires a multidisciplinary approach:1

- Airway assessment and management

- Specialist feeding assessment: advice and training may be given on the use of special feeding bottles and teats if the baby is having trouble feeding. Some babies require the placement of a nasogastric tube and anti-reflux medication.

- Newborn hearing test: children with a cleft palate will be regularly reviewed by specialist cleft ENT and audiology teams.

- Psychological support: from a counsellor, specialist nurse or psychologist.

- Dental health education and advice

- Counselling the parents on future surgical options

- Monitoring for signs and symptoms of genetic syndromes associated with a cleft

- Genetic counselling: this may provide the parents with information about what has caused the cleft and the likelihood of it happening again with future children.

Cleft lip repair

Initial cleft lip surgery is usually performed when the child is at least three months old.

This typically takes 1 to 2 hours to complete under general anaesthetic. Patients are typically required to stay in hospital overnight and can usually return home once they are drinking adequately and are comfortable.1

Potential complications of cleft lip repair may include:12

- Anaesthetic risks

- Post-operative bleeding

- Infection

- Airway obstruction

- Damage to deeper structures

- Hypertrophic or keloid scar

- Wound dehiscence

- Notching of the lip vermilion (the red part of the lip)

The Millard technique

One commonly used surgical technique to repair a unilateral cleft lip is the rotation-advancement technique, which is also known as the Millard technique.

This technique involves making several incisions in the lip to create a rotational flap from the medial segment of the cleft and an advancement flap from the cleft’s lateral segment. These flaps can then be brought together and sutured to correct the cleft in the muscle, subcutaneous tissue and skin.13

Cleft palate repair

Palatoplasty to repair a cleft palate usually takes place when the child is 6-12 months old so the child’s cleft palate will not prevent adequate speech and language development.1

The aim is to correct the palatal defect and reattach the soft palate muscles to create a normally functioning velopharyngeal mechanism.2

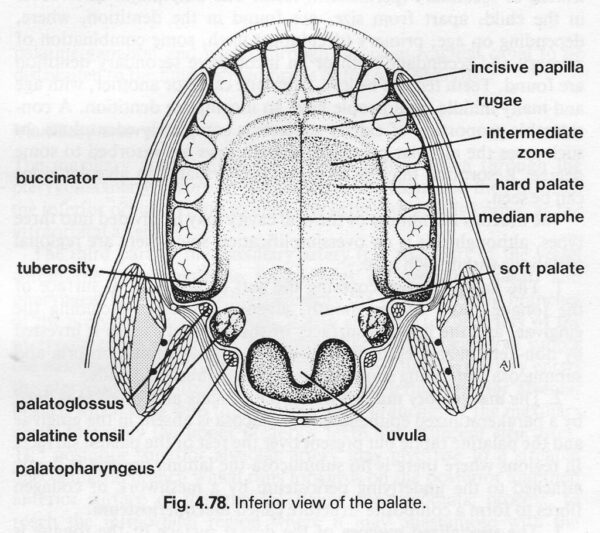

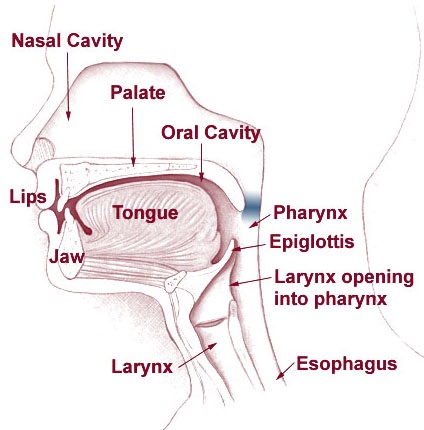

The velopharyngeal mechanism

The velopharyngeal mechanism functions to separate the oral and nasal cavities during swallowing and speech.

The velopharyngeal port is the passage between the nasopharynx and oropharynx. The velopharyngeal mechanism consists of a muscular valve that extends from the back of the hard palate to the posterior pharyngeal wall and includes the soft palate (the velum) and the sides of the throat (lateral pharyngeal walls).

Several different velopharyngeal muscles contract when swallowing to close off the velopharyngeal port by creating a tight seal between the velum and pharyngeal walls, thus preventing communication between the oral and nasal cavities.16

There are five palate muscles that are reconstructed during a palatoplasty:18

- Tensor veli palatini

- Levator veli palatini

- Palatoglossus

- Palatopharyngeus

- Musculus uvulae

The most important muscle to reconstruct is the levator veli palatini as it elevates the soft palate during swallowing and speech. It is therefore essential for the velopharyngeal mechanism. Failure to reattach this muscle properly can lead to velopharyngeal insufficiency and result in nasal reflux during swallowing and hypernasal speech.2

Potential complications of cleft palate repair may include:19

- Anaesthetic risks

- Post-operative bleeding

- Infection

- Airway obstruction

- Damage to deeper structures

- Wound dehiscence

- Total or partial flap necrosis

- Oronasal fistula formation

- Hanging palate

- Poor speech outcomes and the need for further speech surgery

Ongoing management

After the initial repair of their cleft lip and/or palate, patients will require regular follow-up until they are around 20 years of age. This may include:21

- Regular audiology assessment of children with cleft palate until around 5 years of age

- Speech and language therapy

- Ongoing psychological support

- Paediatric dentistry advice and treatment

- Orthodontic assessment and treatment if required at around 10 years old

- Monitoring of previous surgical sites for complications and assessing whether further surgery is necessary

Further surgery

Further surgery may also be required, which may include:22

- Palatal fistulae closure

- Speech surgery (e.g. palatal lengthening)

- Alveolar bone graft

- Lip and/or nasal revision surgery (cleft rhinoplasty)

- Orthognathic surgery

- Restorative dental surgery

Palatal fistulae closure

Following a palatoplasty, the tissues may heal in such a way that an oronasal fistula through the palate is created. This may cause nasal regurgitation during swallowing and speech problems, and so is often closed in a palate revision surgery (secondary palatoplasty).22

Speech surgery

Speech surgery may be offered to children aged 4-6 who still have hypernasal speech from velopharyngeal mechanism insufficiency, despite their cleft palate being closed.

Such speech operations include palatal lengthening with a double-opposing Z-palatoplasty (Furlow’s) or a posterior pharyngeal flap secondary palatoplasty, which is where a square of tissue from the back of the throat is attached to the palate, can be used to block some of the air leaking from the nose.22

Alveolar bone graft (ABG)

An alveolar bone graft is performed when there is insufficient bone around the alveolar (gum line) defect for the adult teeth to erupt properly.

Bone marrow (cancellous bone) is taken from the iliac crest and grafted into the cleft defect to improve the bone support for the adult teeth and allow the orthodontist to align the teeth in the cleft area.

This procedure is usually completed at around 9-11 years old, once all the baby teeth have been lost, but before the child’s lateral incisors or upper canines have erupted through the gum.22

Cleft rhinoplasty

Revision surgery can be completed at any age to improve the contour or shape of the lip and/or nose. However, it is often suggested to delay revision surgery until the patient has finished growing at around 16 years of age or older to prevent the need for extra revision surgeries.22

Orthognathic surgery

Orthognathic surgery involves re-aligning the upper and lower jaws to improve the function of the patient’s bite and side profile. It is offered when there are jaw problems which can’t be treated with orthodontics alone. Orthognathic surgery is performed by a maxillofacial surgeon in conjunction with an orthodontist.21

Jaw surgery is completed after growth stops, which is usually around the age of 14-16 years in girls and 17-21 years in boys.23

Restorative dental surgery

A restorative dentist may replace missing teeth with fixed or removable prosthetics, and tooth-coloured fillers can be used to reshape the teeth to improve how they look. They can also treat any complex gum or tooth root issues.

This treatment can often not be completed until all the patient’s orthodontic treatment has been completed and all their adult teeth have erupted.24

Key points

- A cleft lip forms when there is a problem with lip development during weeks 5-6 of pregnancy.

- A cleft palate forms when there is a problem with the development of the hard or soft palate during weeks 5-12 of pregnancy.

- There is no identifiable cause in around 85% of cases. 15% of cases arise secondary to conditions such as 22q11.2 microdeletion (DiGeorge) syndrome, Pierre-Robin sequence or Treacher-Collins syndrome.

- A family history of cleft as well as alcohol use, smoking and obesity during pregnancy may all increase the likelihood of a cleft.

- Some epilepsy medications such as topiramate and sodium valproate may also increase the risk if taken during the first trimester.

- A cleft lip and/or palate is usually diagnosed at a 20-week anomaly ultrasound scan. It may be diagnosed immediately at birth or during the newborn physical examination (NIPE).

- Surgical treatment may include cleft lip repair, cleft palate repair, alveolar bone grafts, speech surgery, lip or nose revision surgery, orthognathic surgery, and restorative dental surgery.

- Other treatments may include speech and language therapy, orthodontic treatment, psychological support, and regular audiology assessment.

- A cleft lip or palate may cause feeding problems and can affect self-confidence. A cleft palate can result in glue ear and problems with teeth and speech development.

Reviewer

Mr David Sainsbury

Consultant Cleft and Plastic Surgeon

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Cleft Lip and Palate Association (CLAPA). What is Cleft Lip & palate? Published October 2015. Available from [LINK].

- StatPearls. Cleft palate. Published November 2021. Available from [LINK].

- BruceBlaus via Wikimedia Commons. Diagram showing how unilateral and bilateral cleft lip and palate may look. [CC BY-SA 4.0].

- John Doran. Inferior view of the bony palate. [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0].

- John Doran. Inferior view of the soft and hard palate. [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0].

- BAPRAS. Cleft lip and palate. Published in 2015. Available from [LINK].

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA). Cleft lip and palate. Available from [LINK]. Accessed 28th September 2022.

- NHS. Cleft lip and palate. Published August 2019. Available from [LINK].

- Center for disease control and prevention (CDC). Cleft lip and palate. Published in December 2020. Available from [LINK].

- Cleft Lip and Palate Association (CLAPA). What causes a cleft? Published in November 2015. Available from [LINK].

- Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH). Palate examination: Identification of cleft palate in the newborn – best practice guide. Published in 2015. Available from [LINK].

- Nigerian Medical Journal. Postoperative complications from primary repair of cleft lip and palate in a semi-urban Nigerian teaching hospital. Published in May 2016. Available from [LINK].

- StatPearls. Cleft Lip Repair Medical Reference. Published in September 2022. Available from [LINK].

- Buiting via Wikimedia commons. Millard repair procedure for repairing a cleft lip – incision lines (image 1 of 2). [CC BY-SA 3.0]

- Buiting via Wikimedia commons. Millard repair procedure for repairing a cleft lip – completed incisions and suture lines (image 1 of 2). [CC BY-SA 3.0].

- Perry JL. Semin Speech and Language. Anatomy and physiology of the velopharyngeal mechanism. Published in May 2011. Available from [LINK].

- Squirrel, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Diagram of the anatomy associated with the velopharyngeal mechanism.

- Crest and Oral-B Dentalcare.com. Head and Neck Anatomy: Part 2 – Musculature. Published April 2022. Available from [LINK].

- Deshpande GS, Campbell A, Jagtap R, Restrepo C, Dobie H, Keenan HT, Sarma H. Early complications after cleft palate repair: a multivariate statistical analysis of 709 patients.Published in September 2014. Available from [LINK].

- Claudia Krebs, Monika Fejtek, Stacey Skoretz, et al. University of British Colombia. Drawing origins and insertions of the soft palate muscles – English. Licence: [CC BY-NC-SA]

- Cleft Lip and Palate Association (CLAPA). Treatment timeline. Published in October 2015. Available from [LINK].

- University of Iowa Stead Family Children’s Hospital. Cleft palate surgical procedures. Published in February 2012. Available from [LINK].

- Mayo clinic. Jaw Surgery. Published in January 2018. Available from [LINK].

- Cleft Lip and Palate Association (CLAPA). Dentists and clefts: A look at the role of restorative dentists in a cleft lip team. Published January 2018. Available from [LINK].