- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

The term shoulder dislocation refers to the complete displacement of the humeral head from the glenoid fossa, while shoulder subluxation refers to the partial displacement of the humeral head from the glenoid fossa without complete dislocation.

Shoulder dislocations are the most common joint dislocations in clinical practice, accounting for 50% of cases. This is due to the instability of this joint arising from a small portion of the humeral head articulating with a shallow glenoid fossa and an extensive range of movement in all planes.

The shoulder may dislocate anteriorly, posteriorly or inferiorly, with 95-97% of cases being anterior dislocations.1

Aetiology

Clinical anatomy of the glenohumeral joint

The shoulder, or glenohumeral joint, connects the upper arm to the chest. It provides articulation between the glenoid fossa of the scapula and the head of the humerus. These articulating surfaces are separated by a narrow cavity filled with synovial fluid, making it a synovial joint.

The shoulder joint is an example of a ball and socket joint, which is highly mobile due to the minimal contact between its two articulation points, allowing for a wide range of movement. This extra mobility does, however, come at the expense of joint stability.

The shoulder joint is made up of several structures, including:

- Bones: scapula, humerus and clavicle

- Muscles: rotator cuff muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis), deltoid, pectoralis major, teres major

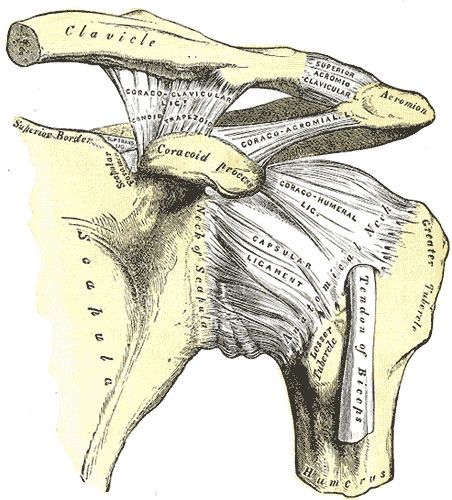

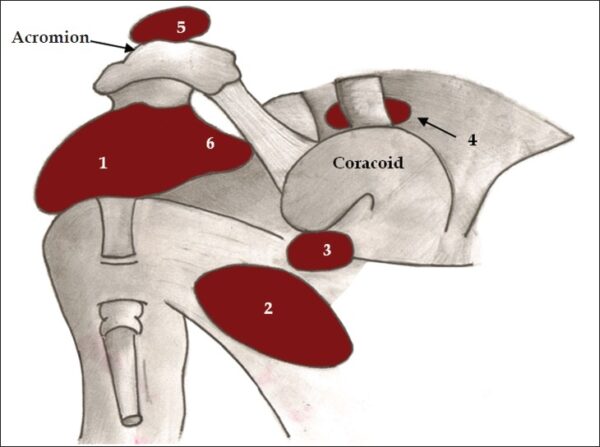

- Ligaments: glenohumeral, coracohumeral, coracoacromial, transverse humeral (Figure 1)

The joint is stabilised by the glenoid labrum, a fibrocartilage rim that deepens the glenoid fossa and helps increase joint stability.

The joint is enclosed within a capsule, which is a fibrous sheet extending from the anatomical neck of the humerus to the rim of the glenoid fossa and houses synovial fluid.

The glenohumeral joint houses two bursae, which are filled with synovial fluid and function to decrease friction between tendons, bone, muscle and skin during movement. The subacromial bursa is found between the acromion and the supraspinatus tendon, while the subscapular bursa is located between the subscapularis tendon and the scapula.

Shoulder stability is improved by the rotator cuff muscles, which attach to the humerus and fuse to the joint capsule, compressing the humeral head into the glenoid cavity. Additionally, the glenoid labrum, the surrounding ligaments as well as the biceps tendon, which acts as a humeral head depressor, also contribute to overall stability.3

Pathophysiology4

Anterior shoulder dislocation

This is the most common type of dislocation and is called ‘anterior’ as the humeral head is dislocated outside of the glenoid fossa and lies anterior to it. The most common mechanism of injury is an impact to the abducted and externally rotated arm. Other mechanisms of injury may be force applied to the posterior aspect of the humerus and falling on the outstretched arm.

The arm is usually held in an abducted and externally rotated position with a prominent acromion. Nerve damage, tears of the glenoid labrum and fractures of the humeral head and glenoid fossa are present in 40% of cases.

Posterior shoulder dislocation

In these shoulder dislocations, the humeral head is displaced posterior to the glenoid fossa of the scapula.

This type of dislocation is more commonly encountered in young athletic individuals. Risk factors include bony abnormalities such as glenoid retroversion or hypoplasia and ligamentous laxity. It also commonly follows tetanic muscle contraction, such as in seizures and electrocution.

These patients present with a flexed, adducted and internally rotated arm. Posterior shoulder dislocations carry a higher risk of associated injuries than anterior dislocations. Common associated injuries include surgical neck and lesser tuberosity fractures of the humerus, reverse Hill-Sachs lesions (impaction fracture of the anteromedial aspect of the humeral head) and avulsion of the posterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament.

Inferior dislocations

This is the rarest type of shoulder dislocation and is usually caused by high-energy trauma leading to hyperabduction or axial loading on the abducted arm. These forces lead to inferior displacement of the humeral head in relation to the glenoid fossa.. The arm is fixed in abduction and held in the overhead position.

Inferior dislocations carry the highest rate of associated injuries. Rotator cuff muscle injuries, internal capsule tears, axillary neurovascular injuries and brachial plexopathies are commonplace in such dislocations.1

Clinical features

History

The typical history of a shoulder dislocation entails a sudden ‘popping out’ or ‘rolling out’ of the shoulder during trauma, accompanied by sudden onset of pain and decreased range of motion. It is very important to enquire about the position of the shoulder joint at the point of dislocation to determine the likelihood and nature of associated injuries.

It is important to determine if this is the first episode of shoulder dislocation or a recurrent problem, as hyperlaxity may be present in recurrent cases. In such cases, the shoulder may roll back into place automatically or with minimal effort.

Clinical examination

The most common finding on shoulder examination in all dislocation types is a painful shoulder leading to diminished active and passive range of motion.

In anterior dislocation, the humeral head is felt prominently anteriorly, and a void or recess becomes evident posteriorly. To assess for anterior shoulder instability, the shoulder can be placed in the vulnerable orientation described previously and the test is positive if apprehension is elicited.

Posterior dislocations are easier to miss as the arm seems to be in its natural position before further examination. On closer inspection, the arm is adducted and internally rotated. In thinner patients, a prominent humeral head may be palpated posteriorly.

A neurovascular examination should be performed and documented before and after reduction. A common finding on neurological examination is axillary nerve damage, which gives motor innervation to the deltoid and teres minor, as well as sensory innervation to the regimental patch.5

Differential diagnoses

Other pathologies that may present similarly with shoulder pain and decreased range of motion include:

- Bicipital tendinopathy

- Acromioclavicular joint injuries

- Rotator cuff injuries

- Clavicle fractures

Investigations

Shoulder X-ray

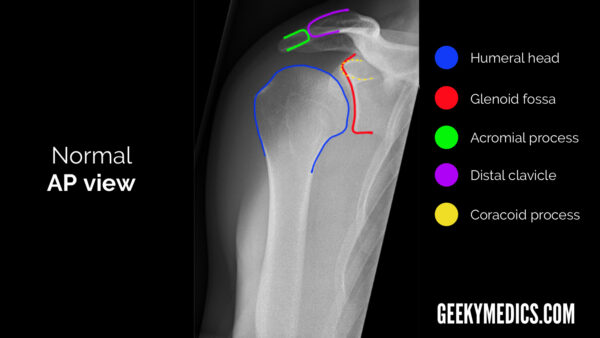

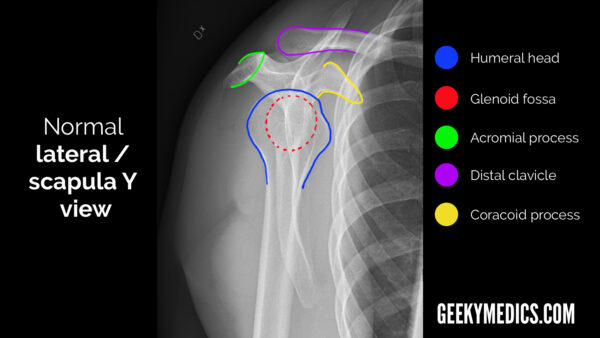

Shoulder X-rays are the main investigation required to diagnose a shoulder dislocation. Typical views include an anterior-posterior (AP) and a scapular “Y” view. An axial view may provide additional information where there is diagnostic uncertainty.

The following two images demonstrate the normal anatomy of the shoulder girdle as seen in the typical AP and scapular Y views.

Anterior shoulder dislocations are easily spotted on both AP and scapular Y views (Figure 5). The following AP view shows a typical anterior dislocation with the humeral head lying in an anterior, medial and inferior position relative to the glenoid fossa.

The ‘light bulb sign’ suggests a posterior shoulder dislocation (Figure 3). The Y-view can help differentiate between anterior and posterior dislocations.

Radiographs are also important to assess for associated fractures which occur in 25% of dislocations. The following are the most frequently encountered associated fractures:

- Fractures of the tuberosity or surgical neck: these dislocations may not be suitable for closed reduction in the emergency department

- Bankart lesions: these develop when the glenoid labrum is damaged; they may sometimes be associated with an avulsion fracture (bony Bankart)

- Hill-Sachs lesions: compression fractures of the posterolateral humeral head commonly occurring in anterior dislocations

- Reverse Hill-Sachs lesions: an impaction fracture of the anteromedial humeral head commonly occurring in posterior dislocations

If plain radiographs cannot be obtained, a CT scan should be requested.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

This is useful in identifying ligamentous injuries which may occur during the dislocation process.

MRI is also useful in assessing for associated rotator cuff tendon ruptures. These are more common in those older than 45 years of age and may be suggested by marked weakness when strength testing the rotator cuff muscles.6

Management

Reduction of the dislocated shoulder

Over 20 shoulder reduction techniques are described in the literature. No consensus exists over the best approach to use, and the technique of choice depends largely on the experience and expertise of the treating clinician.

Understanding several techniques can be useful when faced with a difficult reduction.

The Milch technique: this involves gentle abduction and external rotation of the arm with the patient lying supine. If the shoulder has not spontaneously relocated after the arm is abducted and externally rotated to 90 degrees, pressure can be applied to the humeral head with the thumb to guide it into place.7

The Stimson technique: the patient lies prone, and their arm is allowed to dangle down from a couch. The practitioner applies Gentle downward traction or attaches weights to the wrists. External rotation of the arm may help with the reduction.8

The traction-countertraction method: this technique involves the use of an assistant to provide countertraction. The assistant wraps a sheet or towel under the axilla and around the back of the patient to provide countertraction. The clinician performing the manipulation then flexes the elbow and abducts the arm to 90 degrees using the forearm to apply gentle longitudinal traction.7

The Spaso technique: the patient lies supine with the elbow fully extended and the shoulder flexed at 90 degrees. Gentle longitudinal traction and external rotation is then applied.

The Hippocratic method: the patient lies supine and the clinician places the heel of their foot in the axilla while maintaining longitudinal traction to the extended arm. Beware that the pressure applied to the axillary region using this technique can risk causing neurovascular damage or injury to the humeral head.

Sedation and analgesia

A variety of approaches to analgesia and sedation can be employed to ensure the patient is adequately relaxed and pain-free. These include intra-articular local anaesthetic injection, conscious sedation and general anaesthesia.

Conscious sedation requires a minimum of three members of staff (one to perform the procedure, one airway-trained doctor in charge of the sedation and a member of nursing staff). Fentanyl, ketamine, midazolam and propofol are commonly used agents in this setting.

Shoulder reductions performed under procedural sedation should be carried out in the resuscitation room with full monitoring, including pulse oximetry, non-invasive blood pressure monitoring (NIBP), capnography and ECG.

Other methods of providing analgesia exist, including the use of the inhalational agent methoxyflurane (Penthrox). This is less resource-intensive in terms of staff, expertise, and monitoring requirements than procedural sedation.

Post-reduction care

The affected arm should be placed in a polysling for two weeks to minimise range of motion and stabilise the joint until healing. A neurovascular examination should be repeated and documented, and post-reduction imaging should be obtained.

Follow-up with the orthopaedic team should be arranged. Physiotherapy is necessary to restore range of motion, functionality and strength. Future surgical treatment may be necessary in the case of persistent pain, recurrent dislocations, joint instability or associated injuries.

Complications

Recurrent shoulder dislocations are the most common complication, with 5-10% of adults over the age of 40 suffering a repeat dislocation. This figure is significantly higher in patients under the age of 20, where surgical intervention may be needed to prevent recurrence.9

Other complications include vascular compromise (brachial or axillary artery injuries requiring urgent intervention), nerve damage (commonly axillary or brachial plexus injuries), rotator cuff injuries, adhesive capsulitis, osteoarthritis and degenerative changes.

Key points

- Shoulder dislocations are the most common joint dislocations, with anterior shoulder dislocations being the most common

- The mechanism of injury is often trauma to the abducted, externally rotated, and extended arm

- Diagnosis involves history, examination and radiographic imaging

- Over 20 reduction techniques have been described, and it is useful to be familiar with a couple of these methods

- Post-reduction care includes immobilisation in a polysling, neurovascular reassessment, and post-reduction imaging

- Physiotherapy is important for restoring range of motion, functionality, and strength. Surgery may be necessary for persistent issues such as recurrent dislocations or associated injuries

Reviewer

Dr Michael Hardman

Emergency medicine registrar

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Abrams, R. Shoulder dislocations overview, (2023) Available from: [LINK]

- Javed O, Maldonado KA, Ashmyan R. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Muscles. 2023 Jul 24. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. PMID: 29494017. Available from: [LINK]

- Physiopedia. Shoulder (2022). Available at: [LINK]

- StatPearls. Shoulder dislocation. 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- Valerie E Cothran, M. Shoulder dislocation clinical presentation, History, Physical Examination (2022). Available from: [LINK]

- Vinay Takwale & Irfan Khan. Bailey & Love’s short practice of surgery, 27th edition. Chapter 36: Upper limb – pathology, assessment & management

- BMJ Best Practice. Joint dislocation. Available from: [LINK]

- Alkaduhimi, H., Van der Linde, J. A., Flipsen, M., van Deurzen, D. F. P., & van den Bekerom, M. P. J. (2016). A systematic and technical guide on how to reduce a shoulder dislocation. Turkish Journal of Emergency Medicine, 16(4), 155-168.

- UpToDate. Shoulder dislocation and relocation. 2024. Available from: [LINK]

Image references

- Figure 1. Henry Vandyke Carter. Gray 326. License: [Public domain]

- Figure 2. Zameer Hirji. Bursae shoulder joint normal. License: [CC-BY]

- Figure 3 & 4. Geeky Medics

- Figure 5. Case courtesy of Jeremy Jones, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 7132. License: [CC-BY-NC-SA]

- Figure 6. Case courtesy of Mohammad Taghi Niknejad, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 20570. License: [CC-BY-NC-SA]