- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Children and young people are sensitive to dehydration/volume depletion and have different fluid requirements compared to adults.

Intravenous (IV) fluids can be harmful in these patients and it is important that clinicians understand the principles of paediatric fluid prescription.

This article will provide an overview of intravenous fluid prescribing in paediatrics. For adult patients, see the Geeky Medics guide to intravenous fluid prescribing in adults.

Indications for IV fluid

Where possible, oral fluids (e.g. oral rehydration solution) via the oral or nasogastric route should be used.

However, there are certain situations where the oral route is contraindicated or impractical. In these cases, it is necessary to determine the indication for fluids, type of fluid and volumes/infusion rate required.

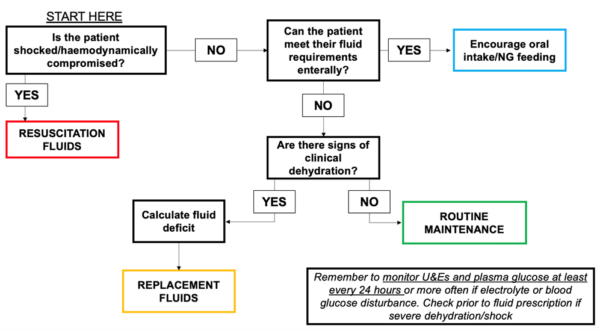

Broadly there are three indications for IV fluids in infants and children: routine maintenance, replacement and resuscitation.1

Routine maintenance

Routine maintenance fluid therapy is required if the current oral intake is not sufficient to remain hydrated.

For example, if the patient is ‘nil by mouth’ for any significant period, full maintenance fluids will be required.

Alternatively, if the patient can obtain some of their intake orally, but is not completely meeting their fluid requirements, they may be given a percentage of full maintenance fluids based on their intake.

Replacement2

Replacement fluid therapy is required if there is an existing fluid deficit and the oral route is not possible or impractical.

Examples of clinical situations where this may occur include:

- Prolonged poor oral intake

- Vomiting

- Diarrhoea

- Increased insensible losses (e.g. fever, excessive sweating)

- Diabetic ketoacidosis

- Burn injuries

Resuscitation3

Resuscitation is required if the patient is shocked. Types of shock and their underlying causes include:

- Hypovolaemic: gastroenteritis, burns, diabetic ketoacidosis, heatstroke, haemorrhage

- Distributive: sepsis, anaphylaxis, neurological injury (neurogenic)

- Cardiogenic: congenital heart disease, arrhythmia

- Obstructive: cardiac tamponade, tension pneumothorax, congenital heart disease

Assessment of volume status

To determine the indication for IV fluids it is important to take a focussed history and examine the child.

The volume status of the child should be assessed looking for features of clinical dehydration or shock.

The current NICE guidelines for IV fluid prescription in children and young people outline the diagnosis of dehydration or shock based on the presence of the clinical features listed below.1

Clinical dehydration

Clinical features suggesting dehydration include:

- Appears unwell/deteriorating*

- Altered responsiveness (irritable, lethargic)*

- Sunken eyes*

- Tachycardia*

- Tachypnoea*

- Reduced skin turgor*

- Dry mucous membranes (not reliable if the child is mouth breathing or just after a drink)

- Decreased urine output

*These clinical features are red flags, the presence of which may predict a higher risk of progression to shock.

Clinical shock

Clinical shock is defined by the presence of one or more of:

- Decreased level of consciousness

- Pale or mottled skin

- Cold extremities

- Pronounced tachycardia

- Pronounced tachypnoea

- Weak peripheral pulses

- Prolonged capillary refill time

- Hypotension

Children have a large physiological reserve. They will compensate until they become very unwell and then deteriorate rapidly.

Hypotension is a sign of decompensated shock and indicates that the child is critically unwell.

Routine maintenance fluid

Choice of fluid

Child (>28 days of age)

For a child (>28 days of age), first line maintenance fluid is usually isotonic crystalloids + 5% glucose (e.g. 0.9% sodium chloride + 5% glucose).

Term neonate (<28 days of age)

The choice of fluid depends on the clinical situation:

- No critical illness:10% dextrose +/- additives

- Critical illness (e.g. infantile respiratory distress syndrome, meconium aspiration): seek expert advice (use fluids with no/minimal sodium initially)

Calculation of fluid requirements

There are specific formulae for calculating the volumes of maintenance fluids in paediatrics.

There are different formulae for patients in the neonatal period, which is up to 28 days of age, and for those who are older.

Children (>28 days of age)

Routine maintenance fluids for children are calculated by weight using the Holliday-Segar formula:1,5

- 100 ml/kg/day for the first 10kg of weight

- 50 ml/kg/day for the next 10kg of weight

- 20 ml/kg/day for weight over 20kg

An online calculator for routine maintenance fluids by the Holliday-Segar formula can be found here.5

Worked example: maintenance fluid

Calculate the 24-hour maintenance fluids and hourly infusion rate for a 40kg child:

- 1000 mL/day for the first 10kg

- 500 mL/day for the next 10kg

- 400 mL/day for the final 20kg

Total = 1900 mL/24h

The next step is to calculate the infusion rate in mL/hour

For the above case, this would be 1900/24 which equals 79 mL/h

Neonates (<28 days of age)

Maintenance for term neonates is calculated according to their age and weight:1

- Birth to day 1: 50-60 ml/kg/day

- Day 2: 70-80 mL/kg/day

- Day 3: 80-100 mL/kg/day

- Day 4: 100-120 mL/kg/day

- Days 5-28: 120-150 mL/kg/day

Replacement fluids (dehydration)

For patients with dehydration without clinical features of shock, rehydration via the oral or nasogastric route is preferred.

If this is impractical or contraindicated, IV fluid therapy may be considered with volumes based on the percentage-dehydration.

Choice of fluid

Replacement fluids should be adjusted according to existing electrolyte excess or deficit and any anticipated ongoing losses (e.g. diarrhoea).

Use isotonic crystalloid that contains sodium with added glucose (e.g. 0.9% sodium chloride + 5% glucose).

If there are ongoing losses (e.g. diarrhoea, vomiting) supplement with potassium (e.g. 10 mmol/L).

The U&Es and plasma glucose should be monitored at least every 24 hours, or more frequently if there are electrolyte abnormalities.1

Calculating percentage dehydration

Percentage dehydration may be calculated either clinically or by weight.4

Calculating percentage dehydration by weight

If a recent and accurate weight for the child is available from a time that they were well, the percentage-dehydration can be calculated by comparing this ‘well weight’ with their current weight.

The difference between the two weights represents the volume of fluid that has been lost. The formula for calculating this is:

Calculating percentage dehydration by clinical assessment

Often a reliable and recent weight is not readily available so the level of dehydration must be estimated clinically.

In clinical practice, this is often difficult to accurately estimate.

Clinical signs of dehydration are only detectable when the patient is 2.5 – 5% dehydrated. Therefore, a child that has symptoms/signs of dehydration, but no red flag features will be approximately 5% dehydrated.

If any red flag features of dehydration are present, or the child is clinically shocked, then it is common practice to assume 10% dehydration.

It is important to treat shock rapidly with an initial fluid bolus before replacement fluids are administered.

Calculating a fluid deficit

Once percentage dehydration is known, a fluid deficit is calculated using the following formula:

- Fluid deficit (mL) = % dehydration x weight (kg) x 10

Total fluid requirement

Replacement fluids are given alongside routine maintenance fluids over a 24-hour period and calculated in the following manner:

- Total fluid requirement (mL) = maintenance fluids (mL) + fluid deficit (mL)

Worked example: fluid replacement

A child who weighs 12kg is 5% dehydrated. Calculate their total fluid requirement over 24 hours:

- Fluid deficit = 5% dehydration x 12 x 10 = 600 mL

- Maintenance = 1000mL (100 mL/kg for first 10 kg) + 100mL (50 mL/kg for last 2kg) = 1100 mL

- Total fluid requirement = 1100 mL + 600 mL = 1700 mL/24 hours » 71 mL/hour

Resuscitation fluids

Glucose-free balanced crystalloids (e.g. Hartmann’s solution) are recommended as initial resuscitation fluids.

Boluses of fluid are required if the patient is shocked or haemodynamically compromised.

The standard fluid for resuscitation is 0.9% sodium chloride with no additives via intravenous (IV) or intraosseous (IO) access (if IV access is not possible) in a standard bolus of 10 mL/kg over <10 minutes.1

Exceptions to this rule in which smaller boluses may need to be used:

- Neonatal period (<28 days of age)

- Diabetic ketoacidosis

- Septic shock

- Trauma

- Cardiac pathology (e.g. heart failure)

After the bolus has been administered, the volume status should be re-assessed (e.g. heart rate, respiratory rate, capillary refill time). If the patient is still shocked urgent senior advice should be sought.

If further fluid is required, the paediatric intensive care team should be contacted with consideration of other measures (e.g. inotropic support).

Maintenance fluids after resuscitation

If a resuscitation bolus adequately reverses shock, then the next stage of treatment would be to assess the requirement for fluid replacement.

NICE guidelines advise that after shock has been treated, the fluid deficit and 24-hour replacement fluids should be calculated in the same way as for any other child who was not shocked.1

There is no need to subtract the resuscitation boluses from the total 24-hour fluid requirements.

For a shocked child, we assume 10% dehydration based on body weight. Therefore, to calculate the total 24-hour fluid requirements we would use the following two formulae:

- Fluid deficit (mL) = 10% dehydration x weight (kg) x 10

- Total fluid requirement (mL) = maintenance fluids (mL) + fluid deficit (mL)

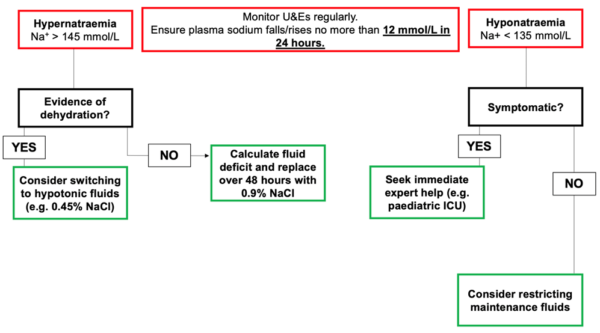

Hypernatraemia and hyponatraemia

In patients with abnormal serum sodium levels, it is important to seek expert help.

Children with hyponatraemia require frequent monitoring of serum electrolytes. If the child is asymptomatic then it may be sufficient to restrict the maintenance fluids and monitor the U&Es until the sodium level normalises.

If there are symptoms of hyponatraemia (altered behaviour, vomiting, convulsions, reduced level of consciousness) then advice from the paediatric intensive care team should be sought, who may consider hypertonic boluses (e.g. 2.7% sodium chloride).

Children with hypernatraemia also require frequent monitoring of serum electrolytes. If there is evidence of dehydration, then consider changing to hypotonic fluid (e.g. 0.45% sodium chloride). This will reduce the sodium load being administered.

If there is evidence of dehydration (hypovolaemic hypernatraemia) then care must be taken to correct the deficit slowly over 48 hours, unless the child is shocked.

For any child with a disturbance in serum sodium, it is important to correct the sodium level slowly with no more than a 12 mmol/L rise or fall in the serum sodium over a 24-hour period.

Rapid correction of severe hyponatraemia can lead to central pontine myelinolysis and rapid correction of severe hypernatraemia may lead to cerebral oedema.

Key points

- In infants and children, the oral or nasogastric route for fluids is preferred where possible.

- If the oral route is not possible, IV fluids may be given for maintenance, replacement or resuscitation.

- Maintenance fluids are required where there is insufficient oral intake but no signs of clinical dehydration.

- Maintenance fluids are given over 24 hours and calculated by the weight using the Holliday-Segar formula for children >28 days of age, or by weight and age in neonates.

- Replacement fluids are required where there is an existing fluid deficit and evidence of clinical dehydration on examination.

- Replacement fluids are calculated based on the percentage fluid deficit, which is usually estimated clinically (5% if mildly-moderately dehydrated, 10% if severely dehydrated or shocked) and are given in addition to maintenance fluids over 24 hours.

- Fluid resuscitation is required where the child is shocked or haemodynamically compromised. Glucose-free crystalloids (e.g. 0.9% sodium chloride) are used for resuscitation; usually as a stat bolus of 10 mL/kg.

- In certain conditions, a smaller resuscitation bolus is used. For example, in neonates, children with cardiac failure, septic shock, diabetic ketoacidosis and major trauma.

- Children on IV fluids should have their U&Es and glucose checked once daily.

- Electrolyte disturbance during IV therapy warrants expert input from a consultant paediatrician or paediatric intensivist.

Reviewer

Dr Sunil Bhopal

Senior Paediatric Registrar

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Intravenous Fluid Therapy in Children and Young People in Hospital [NG29]. Published in June 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- Vega RM, Avva U. Pediatric Dehydration. Published in 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- Pasman EA, Watson CM. Shock in pediatrics. Published in 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- pRRAPID: University of Leeds. Prescribing fluids in children. Available from: [LINK]

- Holliday M. Maintenance Fluids Calculations. MDCalc. Available from: [LINK]

Figures

- Figure 1. NICE. Adapted algorithm for fluid management in children and young people in hospital. Available from: [LINK]. Subject to Notice of rights.

- Figure 2. Levine MM, Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Muhsen K. Image of reduced skin turgor in an infant with gastroenteritis. License: [CC-BY]. Available from: [LINK]

- Figure 3. NICE. Adapted algorithm for management of hyponatraemia and hypernatraemia during fluid therapy. Available from: [LINK]. Subject to Notice of rights.