- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Intravenous (IV) fluid prescribing in adults is something that most doctors do on a daily basis and it’s certainly something you need to understand as a medical student. It can, at first glance, appear intimidating, but the current NICE guidelines are fairly clear and specific, with a handy algorithm you can follow. This article is based upon those guidelines, with some additional information surrounding fluid types, assessment of fluid status and how to apply the guidelines (using a worked example).

Indications for IV fluids

Intravenous (IV) fluids should only be prescribed for patients whose needs cannot be met by oral or enteral routes. Where possible oral fluid intake should be maximised and IV fluid only used to supplement the deficit.

Examples of when IV fluids may be required:

- A patient is nil by mouth (NBM) for medical/surgical reasons (e.g. bowel obstruction, ileus, pre-operatively)

- A patient is vomiting or has severe diarrhoea

- A patient is hypovolaemic as a result of blood loss (blood products will likely be required in addition to IV fluid)

Types of fluids

IV fluids can be categorised into 2 major groups:

- Crystalloids: solutions of small molecules in water (e.g. sodium chloride, Hartmann’s, dextrose)

- Colloids: solutions of larger organic molecules (e.g. albumin, Gelofusine)

Colloids are used less often than crystalloid solutions as they carry a risk of anaphylaxis and research has shown that crystalloids are superior in initial fluid resuscitation. ²

Commonly used fluids

| FLUID TYPE | TONICITY | Na + (mmol/L) | K + (mmol/L) |

Cl – (mmol/L) |

HCO3– (mmol/L) |

GLUCOSE (mmol/L) |

| Human plasma (for comparison) | N/A | 135-145 | 3.5- 5.0 | 100-110 | 22-26 | 3.5-7.8 |

| Sodium chloride 0.9% (Normal saline) | Isotonic Used for resuscitation/maintenance |

154 | 154 | |||

| Hartmann’s solution | Isotonic Used for resuscitation/maintenance |

131 | 5 | 111 | 29 | |

| Sodium chloride 0.18% / Glucose 4% | Hypotonic Used for maintenance |

30 | 30 | 40g/L | ||

| 5% Dextrose | Hypotonic Used for maintenance |

50g/L |

Introduction to prescribing IV fluids

When prescribing IV fluids, remember the 5 Rs:

- Resuscitation

- Routine maintenance

- Replacement

- Redistribution

- Reassessment

To decide what fluids to prescribe, we need to carry out an initial assessment, as discussed in the next section.

Initial assessment

The initial assessment involves assessing the patient’s likely fluid and electrolyte needs from their history, clinical examination and available clinical monitoring (e.g. vital signs, fluid balance). Your clinical examination and review of available clinical monitoring should be performed using the ABCDE approach, with a focus on the patient’s fluid status.

History

Fluid intake:

- Assess if the patient’s fluid intake been adequate.

Symptoms suggestive of dehydration:

- Thirst

- Dizziness/syncope

Fluid loss:

- Vomiting (or NG tube loss)

- Diarrhoea (including stoma output)

- Polyuria

- Fever

- Hyperventilation

- Increased drain output (e.g. biliary drain, pancreatic drain)

Co-morbidities:

- Heart failure

- Renal failure

Clinical examination and review of clinical monitoring

Airway

- Is the airway patent?

Breathing

- Respiratory rate and oxygen saturation

- Auscultate the lung fields

Findings suggestive of hypervolaemia include:

- Increased respiratory rate (>20 breaths per minute)

- Decreased oxygen saturations

- Bilateral crackles on auscultation

Circulation

- Pulse and blood pressure

- Capillary refill time

- Jugular venous pressure (JVP)

- Peripheral oedema

Findings suggestive of hypovolaemia include:

- Increased heart rate (>90 bpm)

- Hypotension (systolic BP <100 mmHg)

- Prolonged capillary refill time

- Non-visible JVP

Findings suggestive of hypervolaemia include:

- Hypertension

- Elevated JVP

Disability

- GCS

Findings suggestive of hypovolaemia include

- Decreased GCS may be noted if the patient is significantly volume depleted.

Exposure

- Wounds

- Drains

- Catheter output

- Abdominal distension/peripheral oedema

- Fluid balance charts/weight charts

- Other losses (e.g. rectal bleeding)

Findings suggestive of hypovolaemia include:

- Increased output from wounds and drains

- Decreased urine output (<30mls/hr)

- A fluid chart showing a negative fluid balance

- Weight loss

- Other sources of fluid loss (e.g. rectal bleeding, diarrhoea, vomiting)

Findings suggestive of hypervolaemia include:

- Increased urine output

- Abdominal distension (ascites) and peripheral oedema

- A fluid chart showing a positive fluid balance

- Weight gain

Next steps

If after your initial assessment you feel there is evidence of hypovolaemia your next step would be to initiate fluid resuscitation as shown in the next section. If however, the patient appears stable and normovolaemic you can skip this step and move straight to calculating maintenance fluids. If you consider the patient to be hypervolaemic, do not administer IV fluids.

Resuscitation fluids

Ok, so you’ve performed your initial assessment and things aren’t looking great, the patient has clinical signs suggestive of hypovolaemia you, therefore, need to prescribe some resuscitation fluids. In addition, you need to start considering the cause of the deficit and take appropriate actions to treat it (e.g. the patient is septic so antibiotics need to be administered).

Initial fluid bolus

1. Administer an initial 500 ml bolus of a crystalloid solution (e.g NaCl 0.9%/Hartmann’s solution) over less than 15 minutes.

Reassess the patient

2. After administering the initial 500 ml fluid bolus you should reassess the patient using the ABCDE approach, looking for evidence of ongoing hypovolaemia as you did in your initial assessment (if you find yourself unsure about whether any further fluid is required you should seek senior input).

3. If the patient still has clinical evidence of ongoing hypovolaemia give a further 250-500 ml bolus of a crystalloid solution, then reassess as before using the ABCDE approach:

- You can repeat this process if there is ongoing clinical evidence suggestive of the need for fluid resuscitation up until you’ve given a total of 2000 ml of fluid.

- If despite giving 2000ml you reassess and find there is still an ongoing need for fluid resuscitation (i.e. persistent hypovolaemia), you should seek expert help.

- If patients have complex medical comorbidities (e.g. heart failure, renal failure) and/or are elderly then you should apply a more cautious approach to fluid resuscitation (e.g. giving fluid boluses of 250 ml rather than 500 ml and seeking expert help earlier).

- If the patient appears normovolaemic but has signs of shock you should seek expert help immediately.

Daily requirements

Once the patient is haemodynamically stable their daily fluid and electrolyte requirements can be considered.

You should review the patient as discussed in the initial assessment section, but also review key laboratory results to better understand the patient’s current fluid and electrolyte status:

- History

- Clinical examination

- Clinical monitoring

- Laboratory monitoring (e.g. electrolytes/renal function/haemoglobin)

Once you have collected the above information you need to decide if you feel the patient can meet their fluid and/or electrolyte needs orally or enterally.

Patient able to meet their fluid and/or electrolyte needs orally/enterally

No further IV fluids should be required.

Patient unable to meet their fluid and/or electrolyte needs orally/enterally

Consider if they have any of the following issues:

- Complex fluid issues

- Electrolyte replacement issues

- Abnormal fluid distribution issues

Those patients who have any of the above issues will likely require fluid replacement and/or redistribution (explained in the associated section below).

Those patients who do not have any of the above issues but are unable to meet their fluid requirement should receive routine maintenance IV fluids (see next section).

Routine maintenance fluids

If a patient is haemodynamically stable but unable to meet their daily fluid requirements via oral or enteral routes you will need to prescribe maintenance fluids. If possible these fluids should be administered during daytime hours to prevent sleep disturbance.

Calculating maintenance fluids

Daily maintenance fluid requirements (as per NICE guidelines):

- 25-30 ml/kg/day of water and

- approximately 1 mmol/kg/day of potassium, sodium and chloride and

- approximately 50-100 g/day of glucose to limit starvation ketosis (however note this will not address the patient’s nutritional needs)

Weight-based potassium prescriptions should be rounded to the nearest common fluids available. Potassium should NOT be manually added to fluids as this is dangerous.

Other factors to consider prior to prescribing

Obese patients

When prescribing routine maintenance fluids for obese patients you should adjust the prescription to their ideal body weight. You should use the lower range for volume per kg (e.g. 25 ml/kg rather than 30 ml/kg) as patients rarely need more than 3 litres of fluid per day.

Other patient groups where you should consider prescribing less fluid

For the following patient groups you should use a more cautious approach to fluid prescribing (e.g. 20-25 ml/kg/day):

- Elderly patients

- Patients with renal impairment or cardiac failure

- Malnourished patients at risk of refeeding syndrome

Reassessment and monitoring

Continue to monitor the patient and reassess regularly:

- Bloods: electrolytes/renal function/haemoglobin

- Clinical examination: hydration status assessment

Stop intravenous fluids once they are no longer required.

Nasogastric fluids or enteral feeding is preferable when maintenance needs are more than 3 days.

Replacement and redistribution of fluids

Some patients will require a slightly different approach than the routine fluid maintenance regimen explained in the previous section.

These are patients who have one or more the following:

- Existing fluid or electrolyte deficits or excesses

- Ongoing abnormal fluid or electrolyte losses

- Redistribution and other complex issues

Existing fluid or electrolyte deficits/excesses

Patients with existing fluid or electrolyte abnormalities require a more tailored approach to fluid prescribing (see basic examples below):

- Dehydration – will require more fluid than routine maintenance

- Fluid overload – will require less fluid than routine maintenance

- Hyperkalaemia – will require less potassium

- Hypokalaemia – will require more potassium

Estimate any fluid or electrolyte deficits/excesses:

- Add or subtract these estimates from the standard routine maintenance fluid regimen discussed in the last section to provide a more tailored fluid prescription.

Ongoing abnormal fluid or electrolyte losses

Recognising ongoing abnormal fluid or electrolyte losses can allow you to tailor your fluid prescription to prevent later complications (e.g. hypokalaemia).

Consider the following sources of ongoing fluid or electrolyte loss:

- Vomiting/NG tube loss

- Diarrhoea

- Stoma output loss (colostomy, ileostomy)

- Biliary drainage loss

- Blood loss (e.g. malaena/haematemesis)

- Sweating/fever/dehydration (reduced or absent oral intake)

- Urinary loss (e.g. diabetes insipidus/post-AKI polyuria)

Estimate amount of ongoing fluid or electrolyte losses (see table for estimates):

- Add or subtract these estimates from the standard routine maintenance fluid regimen discussed in the last section to provide a more tailored fluid prescription.

- The table below is based upon the recent NICE guidelines, check out the diagram that also demonstrates various sources of ongoing losses here.

| TYPE OF FLUID LOSS | APPROXIMATE ELECTROLYTE CONTENT |

| Vomiting/NG tube loss | 20-40 mmol Na+/ l 14 mmol K+/l 140 mmol Cl–/l 60-80 mmol H+/l |

| Diarrhoea/excess colostomy loss | 30-140 mmol Na+/ l 30-70 mmol K+/l 20-80 mmol HCO3–/l |

| Jejunal loss (stoma/fistula) | 140 mmol Na+/ l 5 mmol K+/l 135 mmol Cl–/l 8 mmol HCO3–/l |

| High volume ileal loss via new stoma, high stoma or fistula | 100-140 mmol Na+/ l 4-5 mmol K+/l 75-125 mmol Cl–/l 0-30 mmol HCO3–/l |

| Lower volume ileal loss via established stoma or low fistula | 50-100 mmol Na+/ l 4-5 mmol K+/l 25-75 mmol Cl–/l 0-30 mmol HCO3–/l |

| Pancreatic drain or fistula loss | 125-138 mmol Na+/ l 8 mmol K+/l 56 mmol Cl–/l 85 mmol HCO3–/l |

| Biliary drainage loss | 145 mmol Na+/ l 5 mmol K+/l 105 mmol Cl–/l 30 mmol HCO3–/l |

| Inappropriate urinary loss | Highly variable – monitor serum electrolytes closely. Match hourly urine output (minus 50ml) to avoid intravascular depletion. |

| “Pure” water loss (e.g. fever, dehydration, hyperventilation) | Very little electrolyte content. Can result in potential hypernatraemia. |

Redistribution and other complex issues

Patients can have issues with fluid distribution (e.g. fluid in the wrong compartment) and a collection of other complex issues which should also be considered prior to prescribing IV fluids:

- Gross oedema

- Severe sepsis

- Hypernatraemia/hyponatraemia

- Renal, liver and/or cardiac impairment

- Post-operative fluid retention and redistribution

- Malnourishment and refeeding issues

You should seek senior input for patients with complex issues such as those above to ensure appropriate fluids are prescribed.

Summary

After assessing the patient for:

- existing fluid or electrolyte deficits or excesses

- ongoing abnormal fluid or electrolyte losses

- redistribution and other complex issues

You should:

- prescribe fluid by adding or subtracting any deficits or excesses from routine fluid maintenance, in addition to adjusting for all other sources of fluid and electrolytes (e.g. oral, enteral and medications).

- continue to monitor fluid and biochemical status by clinical and laboratory monitoring, adjusting replacement as appropriate.

Reassessment

Reassessment plays a vital role in fluid prescribing, in both fluid resuscitation and ongoing daily maintenance. A patient’s fluid status is highly dynamic and therefore frequent reassessment will allow you to adjust your fluid prescription to best suit a patient’s needs. It’s particularly important to review if intravenous fluids are still required, to prevent unnecessary administration. Often fluid prescribing guides tell you to decide on a fluid regimen that spans the next 24 hours, however, it is often difficult to predict the clinical course of a patient over that time period. In reality, you would reassess the patient several times over this period and make changes as necessary based on clinical findings and laboratory results.

Reassessing a patient involves repeating the steps discussed in the initial assessment section:

- History

- Clinical examination – fluid status

- Clinical monitoring – vital signs/observations

- Laboratory monitoring (blood tests) – electrolytes/renal function/haemoglobin

Worked example

Mr Smith is a 45-year-old gentleman who has presented to A&E with severe vomiting. He is suspected of having viral gastroenteritis and isn’t currently able to tolerate any oral fluids.

Initial assessment

History of presenting complaint

- Onset/duration – knowing how long he has been vomiting for will be useful in estimating losses

- The volume of vomit produced – this can be somewhat subjective, but it’s useful to ask to enable a more accurate estimation of fluid loss

- Fluid intake – it’s essential to gather information about previous fluid intake

- Urine output – this is another key question as it helps with determining his degree of dehydration (e.g. if he hasn’t passed urine in the last 6 hours, or only highly concentrated urine that would indicate significant volume depletion)

- Other fluid losses:

- Diarrhoea – a common source of fluid loss, particularly in the context of gastroenteritis. Attempt to clarify quantity and details surrounding the stool (e.g. presence of blood).

- Stoma output – it’s important to consider the presence of a stoma, as a significant amount of fluid and electrolytes can be lost via this route.

- Drain output

Past medical history

- Medical co-morbidities relevant to fluid prescribing (e.g. heart failure/renal failure)

Drug history

- It’s important to check what medications a patient is taking in this context.

- Some medications may need to be suspended if this gentleman is dehydrated (e.g. ACE inhibitor).

- In addition, many medications impact serum electrolyte levels.

Patient’s response

“The vomiting started suddenly about 4 hours ago. I’ve vomited over 10 times, I’d say about one litre total, at first there was a lot coming up but now it’s just small amounts, there was never any blood. I’ve not had any diarrhoea thankfully. I’ve only managed a few small sips of water since the vomiting started, it generally just triggers me to vomit. I don’t have any other medical conditions and I’m not on any regular medication.”

- Cool peripheries

- Prolonged capillary refill time (>2 secs)

- Tachycardia/hypotension (including postural)

- Non-visible JVP

- Dry mouth

Mr Smith’s clinical findings

- His peripheries are cold and his capillary refill time is around 4 seconds

- His JVP is not visible

- His mouth is dry and his lips are cracked

Observations:

- Pulse – 105 bpm

- Blood pressure – 90/60 mmHg

- Respiratory rate – 16

- Oxygen saturation (on room air) – 99%

- Apyrexial

- Weight 70 kg

Fluid balance chart:

- Shows he has vomited 100 ml since admission (2 hours ago)

- Shows no fluid intake since admission

Fluid resuscitation

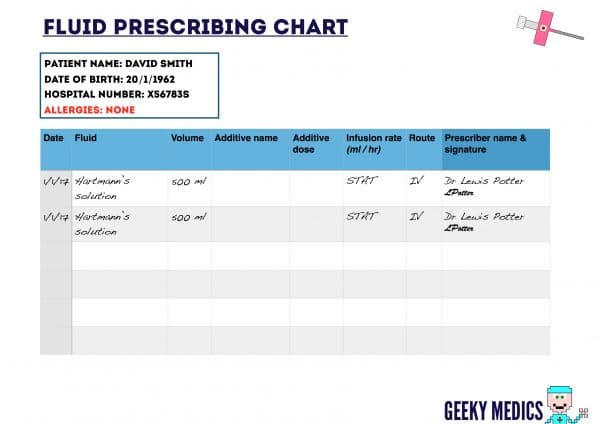

You’ve performed your initial assessment and the patient has evidence of hypovolaemia, so you need to begin fluid resuscitation (download a blank fluid prescription chart here).

- As per the guidelines, this gentleman has evidence of hypovolaemia and therefore requires initial fluid resuscitation with a 500 ml bolus of either NaCl 0.9% or Hartmann’s solution.

- Either would be appropriate, but given this gentleman has been vomiting and thus losing potassium, Hartmann’s is a better choice as it provides some potassium replacement.

- You would give a further bolus of 250-500 ml crystalloid solution and repeat your reassessment.

- This process can be repeated until 2000 ml has been given.

- At that point, if this gentleman was still hypovolaemic you would need to seek senior advice.

- Thankfully this gentleman stabilises after one further bolus of 500 ml Hartmann’s solution: He is normotensive, his pulse is 75 bpm and his mouth is no longer dry.

Daily requirements

The gentleman is now haemodynamically stable, so no further resuscitation fluids are required.

Now that this gentleman has stabilised and requires no further fluid resuscitation you need to assess his likely ongoing fluid and electrolyte needs by reviewing:

- History

- Clinical examination – fluid status

- Clinical monitoring – vital signs/observations

- Laboratory results

Blood test results:

- Na: 140 mmol/L (135-145)

- K: 3.0 mmol/L (3.5-5.0)

- Creatinine: 140 µmol/L (68-110)

- Urea: 7.0 mmol/L (2.5-6.7)

- Hb: 140 g/L – (130-180)

After reviewing these factors you need to consider if the patient is going to be able to meet their fluid and/or electrolyte needs orally. Given that he is still vomiting and feels unable to take in fluids (other than an occasional sip) he is unlikely to be able to meet his needs.

Existing fluid or electrolyte deficits/ongoing abnormal losses

This gentleman has been vomiting fairly large volumes over the last 4 hours, including 100 ml since arriving in hospital. As such he did have a significant fluid deficit, however, this will mostly have been addressed by the 1000ml resuscitation fluid he has been given as a bolus.

The blood tests reveal hypokalaemia, so this would count as an existing electrolyte deficit (likely secondary to vomiting). Estimating his electrolyte loss is possible by knowing the approximate volume of vomit and the approximate electrolyte content of vomit:

- We know he has vomited approximately 1100 ml (1000 ml at home + 100 ml in hospital)

- Using the above chart that shows approximate electrolyte contents of various bodily fluids we can estimate that he has the following electrolyte deficits as a result of vomiting:

- 44 mmol Na+

- 154 mmol Cl–

- 15 mmol K+

- He has already received 1000mls of Hartmann’s which will have replaced most of the electrolyte losses associated with the vomiting. The electrolyte contents of 1000mls of Hartmann’s is as follows:

- Na+ 154mmol

- Cl– 154mmol

- 5 mmol K+

These values need to be remembered, as we will factor them into the eventual routine maintenance prescription, but we first need to also consider ongoing abnormal fluid and/or electrolyte losses.

The key ongoing abnormal loss for this gentleman is vomit. It’s difficult to predict how much vomit he will produce in the next 24 hours, but given…

- he has already produced 1100 ml of vomit

- the volumes of vomit are decreasing somewhat

…a fair estimate would be a further 1000 ml over 24 hours.

Therefore using the table as before we would estimate the following approximate ongoing losses over the next 24 hours:

- 40 mmol Na+

- 14 mmol K+

- 140 mmol Cl–

- 1000 ml fluid

Redistribution and other complex issues

This gentleman is a relatively straightforward case of someone who is otherwise healthy with gastroenteritis, so there are no complex issues to factor in.

Previous electrolyte deficits:

- 44 mmol Na+(this deficit has been fully replaced by the initial 1000mls of Hartmann’s)

- 15 mmol K+(this deficit has been partially replaced by the initial 1000mls of Hartmann’s which contains 5mmol of K+, resulting in a remaining deficit of 10mmol)

- 154 mmol Cl– (this deficit has been fully replaced by the initial 1000mls of Hartmann’s)

Ongoing abnormal losses:

- 40 mmol Na+

- 14 mmol K+

- 140 mmol Cl–

- 1000 ml fluid

Recommended routine maintenance fluids (as per NICE guidelines):

- 25-30 ml/kg/day of water and

- approximately 1 mmol/kg/day of potassium, sodium and chloride and

- approximately 50-100 g/day of glucose to limit starvation ketosis (however, this will not address the patient’s nutritional needs)

So the routine daily requirements for this 70kg gentleman (ignoring his deficits and ongoing losses) are:

- Daily water requirement: 30 ml x 70 kg = 2100 ml

- Potassium: 70 mmol

- Sodium: 70 mmol

- Chloride: 70 mmol

- Glucose: 50-100 grams

We now need to factor in the deficits and ongoing losses:

- Daily water: 2100 ml + (1000 ml estimated loss) = 3100 ml

- Potassium: 70 mmol + (10 mmol previous deficit) + (14 mmol estimated ongoing loss) = 94 mmol

- Sodium: 70 mmol + (no previous deficit as already replaced) + (40 mmol estimated ongoing loss) = 110 mmol

- Chloride: 70 mmol + (no previous deficit as already replaced) + (140 mmol estimated ongoing loss) = 210 mmol

- Glucose: 50-100 grams

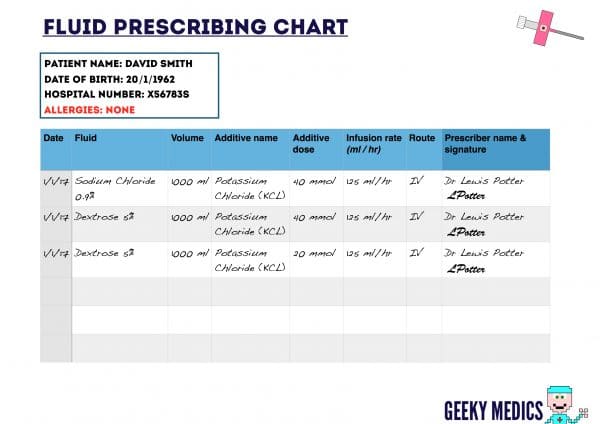

We now need to look at the various fluids available and decide on a regimen that would best accommodate these needs across a 24 hour period. From a pure volume perspective, we need to give 3 litres (e.g. 3 x 1000 ml bags of fluid, each running over 8 hours).

A possible regimen might include the following:

- BAG 1: 1000 ml of NaCl 0.9% + 40 mmol KCL

- BAG 2: 1000 ml of Dextrose 5% + 40 mmol KCL

- BAG 3: 1000 ml of Dextrose 5% + 20 mmol KCL

This would provide the following volume and electrolytes over a 24 hour period:

- Volume: 3000 ml

- Sodium: 154 mmol

- Chloride: 254 mmol

- Potassium: 100 mmol

- Glucose: 100 grams

Comparing this to his requirement below, it’s not a perfect match, but it roughly provides similar amounts of key electrolytes and the appropriate volume:

- Sodium: 110 mmol

- Chloride: 210 mmol

- Potassium: 94 mmol

- Glucose: 50-100 grams

- Volume: 3100 ml

In reality, you would assess the patient on an ongoing basis, adapting the maintenance prescription based on the clinical context. For example, if the patient started eating and drinking after the second bag you might not give any further fluid, or use a fluid without potassium.

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2013 (updated 2016)). Intravenous Fluid Therapy In Adults In Hospital. Available at: [LINK].

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2013 (updated 2016)). Intravenous Fluid Therapy In Adults In Hospital. Research recommendations. Available at: [LINK].