- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

What is palliative care?

Palliative care is a speciality focused on managing the symptoms of patients with life-limiting conditions.1

Palliative care is relevant within all specialities and is not limited to patients reaching the end of their life. However, this is often when the palliative care team becomes involved with patients.

Death affects everyone, with more than half a million people expected to die each year in the UK.2 This will only increase with the ageing population.

A prospective cohort study showed that over a quarter of hospital inpatients will have died within 12 months of discharge.2 During these admissions, we can improve those last 12 months of life and positively impact their death.

Roles of the palliative care team

The main roles of the palliative care team are:

- Maintaining comfort and increasing quality of life for patients

- Alleviating negative symptoms which patients are experiencing

- Helping patients to communicate their needs and concerns

- Communicating with patients (and their families if consent is given) about end-of-life care and what to expect when a patient is approaching the dying phase

- Exploring with patients how they would like to be cared for in the last phases of their life and where they would like to die when the time comes

- Helping patients achieve any goals which are important to them before they die

- Advising responsible medical teams with prescribing anticipatory medications when indicated

Conditions

Palliative care input can be appropriate for all conditions at advanced stages, for example:

- Advanced cancer

- End-stage heart failure

- Renal failure and stopping dialysis

- Surgical emergencies in which the patient is felt not fit for an operation: bowel ischaemia, bowel obstruction/perforation, advanced peripheral vascular disease

- End-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Neurodegenerative conditions

The key reason for referral to palliative care is if the patient is symptomatic, and assistance is needed to manage this. This is referred to as symptom burden.2 Referral is also useful when patients demonstrate high levels of psychological distress about their condition.

Who delivers palliative care?

Palliative care is the responsibility of all medical professionals. The clinicians looking after patients on a day-to-day basis will know the patient’s needs and priorities the best. This may be their GP, ward doctor, district nurse or social worker. GPs, in particular, have a significant role in managing end-of-life care in the community.

Palliative care specialists can give advice or treatment for more complex cases. The best palliative care is delivered when a multi-disciplinary team is involved.

Generalist

Professionals who provide day-to-day palliative care to patients and carers include:

- GPs, district nurses, physiotherapists

- Hospital ward medical teams

- Social care agencies

Specialist

Professionals who provide specialist palliative care include:4

- Hospital palliative care specialist nurses and doctors

- Hospice-based doctors, nurses, social workers, chaplains, complementary therapists, dietitians and psychologists

- Community palliative care specialist nurses

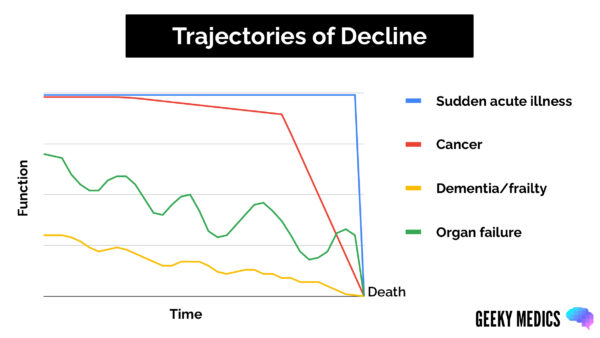

Trajectories of decline

It can be challenging to predict the time scale of a patient declining, as many factors can affect their prognosis, such as:

- Their condition and how aggressive it is

- Their previous functional reserve (how well they were pre-morbidly)

- How actively they are being treated for their medical condition

Patients deteriorate in different patterns depending on their life-limiting condition (Figure 1).5

Assessment tools

Regular assessment and taking a collateral history from relatives can help recognise decline. Many scoring systems can be used to assess if a patient is deteriorating.

Karnofsky Performance Status Scale

The Karnofsky Performance Status Scale is an assessment tool used to assess patients’ prognosis and likelihood of survival. The ranking runs from 100 to 0, where 100 is “perfect” health and 0 is death.6

Table 1. The Karnofsky Performance Status Scale.6

| Score (%) | State of health |

| 100 | Normal; no complaints; no evidence of disease. |

| 90 | Able to carry on with normal activity, minor signs of symptoms of disease. |

| 80 | Normal activity with effort; some signs and symptoms of disease. |

| 70 | Cares for self; unable to carry on with normal activity or to do active work. |

| 60 | Requires occasional assistance but is able to care for most personal needs. |

| 50 | Requires considerable assistance and frequent medical care. |

| 40 | Disabled; requires special care and assistance. |

| 30 | Severely disabled; hospital admission is indicated, although death is not imminent |

| 20 | Very sick; active supportive treatment necessary. |

| 10 | Moribund; fatal processes progressing rapidly. |

| 0 | Dead |

Phases of illness

The phases of illness tool assesses the care needs of the patient and their family and whether a suitable care plan is in place. Patients are split into five categories: stable, unstable, deteriorating, dying and deceased.7 Patients can move between categories in any direction, a change in category indicates a need for re-assessment.

Communicating about deterioration and prognosis

Often, patients and family members will ask how much time is left. It is important to give an indication but not to guarantee anything, as patients’ conditions can change rapidly. Discussing this openly is essential. Often, using a time range can be helpful, for example: ‘hours to short days’, ‘days to weeks’ and ‘weeks to months’.

This can also be an opportunity to ask patients or family what is important to them for that time left. A senior team member should lead this discussion.

Recognising dying

It is helpful to recognise when a patient is entering the dying phase, although this can be difficult and uncertain.

Often, talking to the patient and the family can give you clues that the patient is beginning to die. This can also be an excellent way to start conversations about death and what to expect. Talking about death can be challenging and scary for patients, family members and medical professionals, so feeling confident about how to approach it is key to communicating well.

Signs that a patient may be approaching the end of their life include:8

- Sleeping more than 50% of the day

- Feeling tired when they are awake

- Eating and drinking less, losing their appetite

- Getting out of bed less or not at all

- Finding that small activities use up the majority of their energy

Communicating about death

If you create a safe environment for a patient, they will often tell you that they think they are dying, or a family member may even acknowledge it.

However, asking about the above symptoms and explaining that they indicate time ‘may be short’ is often a good way to start the conversation. It is important to sensitively use the words ‘death’ or ‘dying’ in these conversations so as not to risk miscommunication. Avoid using ambiguous terms such as ‘’passing away’’.9

Anticipatory prescribing at the end of life

Symptoms such as pain, excess secretions and agitation are commonly seen in patients nearing the end of life.

Anticipatory medications are prescribed in advance or ‘in anticipation’ of these symptoms developing. This ensures timely administration, minimising distress and discomfort.

There are four main classes of anticipatory medication:10

- Analgesia: for pain

- Anti-emetic: for nausea and vomiting

- Anxiolytic: for agitation

- Anti-secretory: for respiratory secretions

For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to prescribing anticipatory medications.

Where people die

Patients have a choice about where they would like to be cared for at the end of their life and, ultimately, where they would like to die.

If a patient has a life-limiting illness, this may be included as part of their advance care plan. However, they are always entitled to change their mind as their condition progresses.11

Hospital

Hospital is where most patients die, but not where most patients wish to die. This can be prevented by having early palliative care involvement and good advanced care planning. If a patient deteriorates in hospital then referring to palliative care, moving the patient to a side room, rationalising medications, and considering stopping observations can be helpful.12

Hospice

Hospices are facilities dedicated to patients who have high symptomatic burdens which are difficult to manage at home or in a hospital setting and those who are entering the dying phase.

Hospices are limited by the medical investigations they can perform but provide more on-site support from palliative care professionals than at home.

Home

Home is often where patients want to reach the end of their life. If patients choose to die at home, adjustments to the home environment (e.g. medical equipment such as a hospital bed) are often required.

Extra assistance from carers at home is often needed. District nurses can visit the patients at home and administer anticipatory medications to ease symptom burden.

The process after death

Confirming death

After a patient dies, the death should be confirmed (verified).

Paperwork

A Medical Certificate of Cause of Death (MCCD) should be completed, unless the death needs to be referred to the coroner.

Other paperwork following death may include:

- Coroner’s referral form

- Cremation form

Reviewer

Dr Jeannine Gambin

Palliative care registrar

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Zhukovsky D. Primer of Palliative Care. 2019. Available from: American Association of Hospice and Palliative Medicine.

- NHS England. About palliative and end of life care. 2014. Available from: [LINK]

- Gapstur R. Symptom burden: a concept analysis and implications for oncology nurses. 2007. Available from: [LINK]

- Marie Curie. A guide to end of life services. 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. Illness Trajectories: Description and clinical use. 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- Wikipedia. Performance status. 2015. Available from: [LINK]

- Mather H. Phase of Illness in palliative care: Cross-sectional analysis of clinical data from community, hospital and hospice patients. 2017. Available from: [LINK]

- Marie Curie. Signs that someone is in their last days or hours of life. 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- Marie Curie. Talking to someone about dying. 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- Herbert M Geeky Medics. Anticipatory Prescribing for Patients Nearing the End of Life. 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- Marie Curie. Advance Care Planning. 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- The Choice in End of Life Care Programme Board. What’s important to me. 2015. Available from: [LINK]

.