- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Analgesics are a class of medications designed to relieve pain and are frequently encountered in clinical practice. They include both opioid and non-opioid drugs.

Paracetamol is the most well-known and widely available analgesic in England and was dispensed over 16.38 million times in 2021. Other popular analgesics prescribed were from the opiate class and included codeine-based preparations, tramadol, morphine, and buprenorphine.1

There is increasing awareness of the adverse impact of opiate prescriptions on society, with a push to reduce the amount of inappropriately prescribed high-strength painkillers.2

It is important to understand the principles of prescribing analgesia and the common adverse effects of analgesics, including tolerance, addiction, renal impairment due to non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs), and respiratory depression due to opiates. Prescribing analgesia is commonly tested in the Prescribing Safety Assessment (PSA).

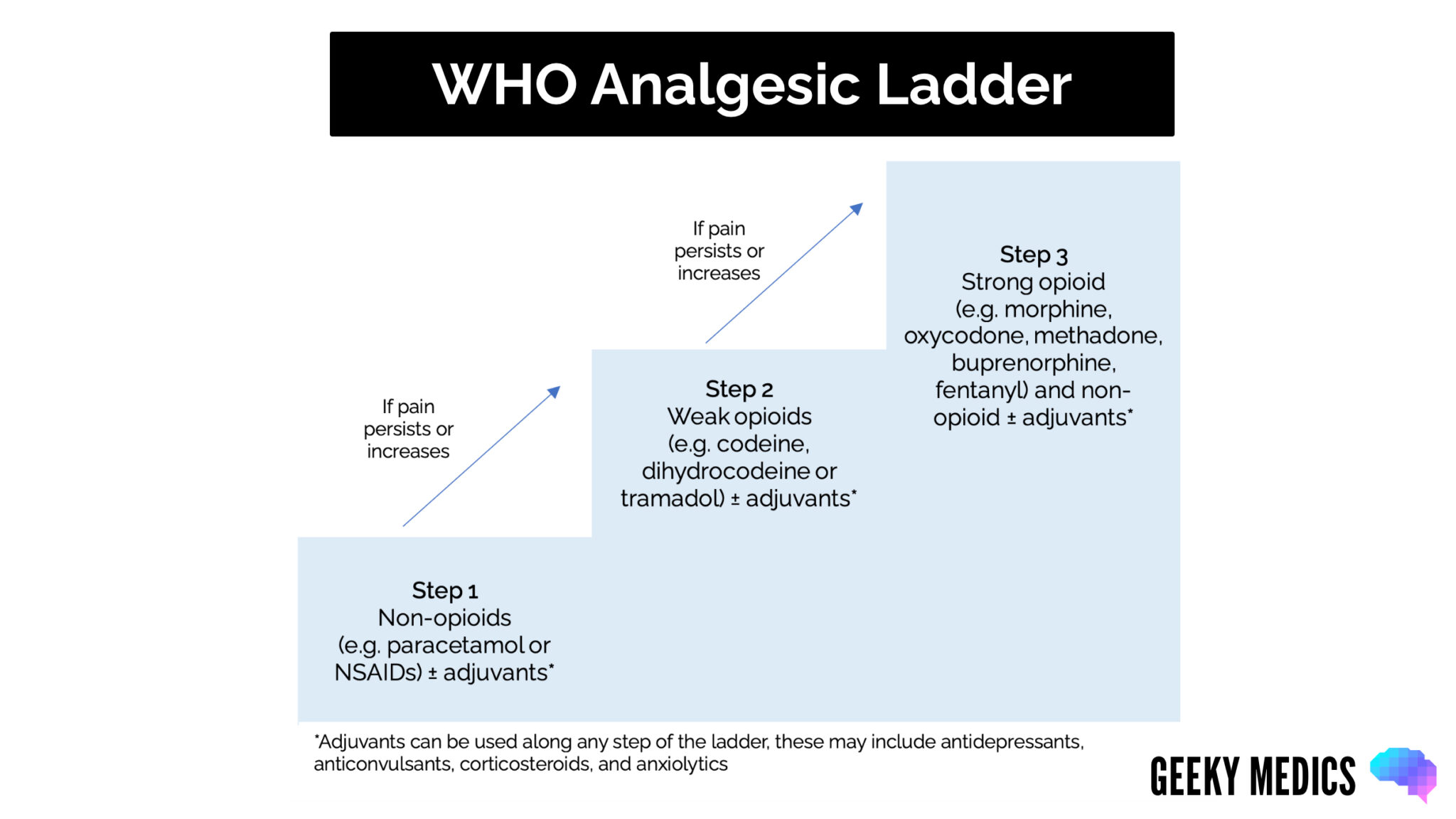

This article will cover the principles of prescribing analgesia, including the World Health Organisation (WHO) analgesic ladder. Always check the BNF before prescribing any drug.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) analgesic ladder

The WHO analgesic ladder (also called the WHO pain ladder) is a good starting point when prescribing analgesia.

Although initially developed for cancer patients, it can also be applied to all patients with acute or chronic pain requiring analgesics. Each drug should be trialled and assessed for efficacy and side effects.

A decision to continue analgesia should be based on improved pain and function with minimal side effects (acceptable to the patient) and where the benefits outweigh the risks.

The WHO analgesic ladder has five key principles:

- Oral administration of analgesics should be used whenever possible

- Analgesics should be given at regular intervals with the duration and dose of medication supporting the patient’s level of pain

- Analgesics should be prescribed according to the pain intensity characterised by the patient (this should be free from judgement from the clinician)

- Dosing of pain medication should be adapted to the individual, starting at the lowest dose and duration possible but titrating accordingly to response

- Consistent administration of analgesics is vital for effective pain management

Opioid analgesics

Although the mechanism of action of different opioids may vary, the prescribing principles are the same.

Side effects

Common side effects of opioids include:

- Constipation

- Drowsiness and impaired concentration: this may impair a patient’s ability to drive

- Nausea & vomiting: common when starting treatment or following a dose increase

- Dry mouth

- Flushing

- Hallucinations

- Headaches

All opioids carry a risk of dependence and addiction.

Longer-term side effects of opioid use include an increased risk of falls, erectile dysfunction, amenorrhoea, infertility, depression, fatigue, and opioid-induced hyperalgesia.5

Managing side effects

- Nausea and vomiting: can be managed with anti-emetics (e.g. cyclizine)

- Constipation: all patients who start strong opioids should be prescribed a laxative to prevent constipation

Opioid toxicity and overdose

The classical clinical toxidrome of opioid overdose is a triad of:

- Reduced consciousness

- Respiratory depression

- Constricted pupils (miosis)

Respiratory depression is a significant concern with opioid analgesics.

For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to opioid overdose.

Renal/hepatic impairment6

Caution is required when prescribing in renal impairment as many opioids (i.e. morphine) are renally excreted, increasing the risk of opioid accumulation and subsequent toxicity.

For patients with renal impairment (eGFR <90), oxycodone is preferred as it is primarily metabolised by the liver, with only a small proportion excreted by the kidney.

Doses should be reduced by 50% in mild renal or hepatic impairment and adjusted according to response.

Specialist advice should be sought before prescribing strong opioids for patients with moderate to severe renal or hepatic impairment.

Other situations

Breastfeeding should be avoided due to the presence of opioids in breast milk.7

When prescribing opioids for the elderly, reduced doses should be used during titration.

Stopping treatment

Cessation of treatment should be tapered slowly to reduce the risk of withdrawal and may take weeks to months.

Prescribing analgesia

Assess the patient to determine the need for analgesia

Involve the patient in a treatment plan and consider their ideas, concerns, and expectations of treatment, and discuss:

- The severity of the pain, its impact on lifestyle and activities of daily living, including sleep disturbance

- The cause of the pain and whether there has been a deterioration

- Why a particular treatment is being offered

- The benefits and adverse effects of pharmacological treatment when considering the patient’s underlying health condition

- The importance of adherence to medication and dosage titration

Consider non-pharmacological methods of pain management (i.e. education, explanation and reassurance, physiotherapy, electrotherapy, mindfulness, or acupuncture).

Step 1: Consider regular paracetamol use8

Patients can buy paracetamol for short-term use for mild-moderate pain. Side effects are relatively uncommon, and paracetamol is regarded as safe.

Paracetamol is primarily metabolised by the liver, so it should be used with caution in hepatic impairment due to an increased risk of toxicity.

Dose adjustments may be needed in severe renal impairment and those who are <50kg.

Drug-drug interactions are relatively uncommon.

Example dosing

Typical drug dosing for (oral) paracetamol:

- Mild to moderate pain: 0.5g – 1g every 4-6 hours; maximum 4g daily

Step 2: Add an NSAID (+/- PPI)8

Patients can buy some NSAIDs (e.g. ibuprofen), while some must be prescribed (e.g. naproxen, diclofenac). They are most commonly used for pain, inflammation, and pyrexia.

Side effects include dyspepsia, peptic ulcer disease and skin reactions. NSAIDs should be taken with, or immediately after, food.

A proton pump inhibitor (PPI) such as omeprazole should be added to reduce the risk of peptic disease.

Contraindications to NSAIDs include:

- Active bleeding or a history of active bleeding

- Ischaemic heart disease

- Severe hepatic impairment

- Renal impairment

- Uncontrolled hypertension

- Asthma

Drug interactions that increase the risk of bleeding include:

- Anticoagulants or antiplatelets (e.g. warfarin or aspirin)

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (e.g. sertraline)

Drug interactions that increase the risk of electrolyte imbalances include:

- ACE inhibitors (e.g. ramipril): increased risk of hyperkalaemia

- Diuretics (e.g. spironolactone): increased risk of hyponatraemia or hyperkalaemia

Drug interactions that increase the risk of seizures include:

- Fluoroquinolone antibiotics (e.g. ciprofloxacin)

Example dosing

Typical drug dosing for (oral) ibuprofen:

- Mild to moderate pain: initially 300-400mg 3-4 times a day; increased up to 600mg 4 times a day if necessary; maintenance 200-400mg three times a day

Typical drug dosing for (oral) naproxen:

- Pain and inflammation in rheumatic disease: 0.5-1g daily in 1-2 divided doses

- Pain and inflammation in musculoskeletal disorders/dysmenorrhoea: initially 500mg, then 250mg every 6-8 hours as required, maximum dose after the first day 1.25g daily

Step 3: Add codeine/co-codamol (weak opioids)11-13

A weak opioid can be codeine alone or combined with paracetamol (co-codamol). Co-codamol comes in three strengths 8/500mg, 15/500mg and 30/500mg. Start at the lowest dose and titrate up as needed.

10% of patients will not respond to codeine. If so, switch to dihydrocodeine.

Remember, opioids are not helpful for mechanical back pain, fibromyalgia or non-specific visceral pain.

Example dosing

Typical drug dosing for (oral) codeine:

- Mild to moderate pain: 30-60mg every 4 hours as required

Typical drug dosing for (oral) co-codamol:

- Titrate up according to the response from mild, moderate to severe pain

- Mild to moderate pain: initially 8/500-16/1000mg every 4-6 hours as required

Typical dosing for dihydrocodeine:

- Moderate to severe pain: 30mg every 4-6 hours as required

Step 4: Stop codeine/co-codamol & trial tramadol (weak opioid)14

Tramadol is an alternative if codeine/co-codamol is ineffective or cannot be tolerated. It can be used for both nociceptive and neuropathic pain. Therefore if responsive, consider whether the pain is truly nociceptive.

Example dosing

Typical drug dosing for (oral, immediate release) tramadol:

- Moderate to severe acute pain: initially 100mg, then 50-100mg every 4-6 hours; usual maximum 400mg/24 hours

Step 5: Reassess the patient

Before continuing to escalate analgesia per the WHO analgesic ladder, reassess and review the patient. This should include an assessment of:

- Pain control

- Impact on lifestyle and activities of daily living

- Physical and psychological wellbeing

- Adverse effects

- The continued need for treatment

Step 6: Stop tramadol & start morphine6,15

Before prescribing any strong opiate, consider ABC:

- Start Antiemetic

- Consider Breakthrough pain

- Prescribe laxatives for Constipation

For patients requiring long-term morphine, consider using a slow-release preparation.

For patients with renal impairment, consider oxycodone.

Example dosing

Typical drug dosing for (oral) morphine:

- Acute pain: initially 10mg every 4 hours; use a lower initial dose in the elderly (5mg every 4 hours)

- Chronic pain: 5-10mg every 4 hours

Typical drug dosing for (oral) oxycodone:

- Severe pain: initially 5mg every 4-6 hours; dose to be increased upon response; maximum 400mg daily; reduce the dose by 50% in those with renal impairment

Step 7: Refer to pain management specialists

At any stage, patients should be referred to pain management specialists if they have the following:

- Severe pain

- Their pain significantly limits their lifestyle or activities of daily living

- Their underlying health condition has deteriorated

Other methods for treating pain include nerve blocks, epidurals, PCA pumps, neurolytic block therapy or spinal stimulators.5

Neuropathic pain

Neuropathic pain is caused by damage to the somatosensory nervous system, which can result in allodynia, hyperalgesia, and paraesthesia.16,17

The common causes of neuropathic pain include:

- Diabetic neuropathy

- Chronic alcohol use

- Infection

- Trigeminal neuralgia

- Trauma

- Spinal cord injuries

- Multiple sclerosis

- Malignancy

Assess the patient to determine the need for treatment (pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment).

Non-pharmacological treatment16,17

Non-pharmacological treatments for neuropathic pain include:

- Physical and psychological treatments

- Surgery

Pharmacological treatment16,17

A choice of pharmacological treatments can be offered to patients with neuropathic pain; first-line options include:

- Amitriptyline

- Duloxetine

- Gabapentin

- Pregabalin

If initial treatment is not effective or tolerated, offer a choice of one of the remaining three drugs.

When withdrawing or switching treatment, the regimen should be tapered.

Amitriptyline18

Amitriptyline is a tricyclic antidepressant. Its mechanism of action is not fully understood, but it is thought to act on multiple neurotransmitter pathways to enhance the effects of certain hormones while inhibiting others.

Typical drug dosing for (oral) amitriptyline:

- Neuropathic pain: initially, 10-25mg daily, in the evening, then increased if tolerated, in steps of 10-25mg every 3-7 days in 1-2 divided doses; usual dose 25-75mg daily.

Doses above 75mg should be used cautiously in the elderly and those with cardiovascular disease.

The most common side effects are anticholinergic:

- Dry mouth

- Blurred vision

- Dry eyes

- Constipation

- Urinary retention

- Postural hypotension

Overdose is associated with a high mortality rate. For more information, see Geeky Medics guide to tricyclic antidepressant overdose.

Duloxetine19

Duloxetine is a selective serotonin noradrenaline uptake inhibitor (SNRI).

Typical drug dosing for (oral) duloxetine:

- Diabetic neuropathy: 60mg once daily, discontinue if no response after 2 months; maximum 120mg daily in divided doses

Use with caution in the elderly and those with cardiovascular disease.

The most common side effects include:

- Anxiety

- Dry mouth

- Flushing

- Gastrointestinal discomfort

- Palpitations

- Sexual dysfunction

Avoid abrupt withdrawal of treatment. Doses should be reduced over 1-2 weeks.

Pregabalin and gabapentin20,21

Gabapentin and pregabalin are commonly known as anticonvulsants. Their mechanism of action is not fully understood, but they are thought to inhibit the release of excitatory neurones.

Typical drug dosing (oral) pregabalin:

- Peripheral and central neuropathic pain: initially 150mg daily in 2-3 divided doses; then titrated up according to the BNF

Typical drug dosing (oral) gabapentin:

- Peripheral neuropathic pain: initially 300mg once daily; then titrate up according to the BNF

Doses should be reduced in patients with renal impairment.

The most common side effects include:

- Drowsiness

- Dizziness

- Ataxia

These usually improve in the first few weeks of treatment.

Other considerations

- Carbamazepine is first line in trigeminal neuralgia

- Consider tramadol only if acute rescue therapy is needed

- Consider capsaicin cream for people with localised neuropathic pain who wish to avoid oral treatments

Reviewer

Dr Satpaul Ubhi

General Practitioner

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- NHS Business Services Authority. Prescription cost analysis – England – 2021- Published in June 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- NHS England. Opioid prescriptions cut by almost half a million in four years as NHS continues crackdown. Published in 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- Medical Defence Union Journal. Prescription errors. Available from: [LINK]

- World Health Organization. Traitement de la douleur cancéreuse. Geneva, Switz: World Health Organization; 1987. Available from: [LINK]

- NICE CKS. Analgesia – mild-to-moderate pain. Available from: [LINK]

- British National Formulary. Oxycodone. Published in 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- NICE CKS. Substance dependence. Available from: [LINK]

- British National Formulary. Paracetamol. Published in 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- British National Formulary: Ibuprofen. Published in 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- British National Formulary. Naproxen. Published in 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- British National Formulary. Codeine phosphate. Published in 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- British National Formulary. Co-codamol. Published in 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- British National Formulary. Dihydrocodeine. Published in 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- British National Formulary. Tramadol hydrochloride. Published in 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- British National Formulary. Morphine. Published in 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- British National Formulary. Neuropathic pain. Published in 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- NICE CKS. Neuropathic pain in adults: pharmacological management in non-specialist settings. Published in 2013. Available from: [LINK]

- British National Formulary. Amitriptyline. Published in 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- British National Formulary. Duloxetine. Published in 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- British National Formulary. Pregabalin. Published in 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- British National Formulary. Gabapentin. Published in 2023. Available from: [LINK]