- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Urticaria is a skin condition characterised by the sudden appearance of itchy, raised wheals (hives), mainly in the upper dermis, which can characteristically last between a few minutes to 24 hours.

Angioedema

Urticaria can co-exist with angioedema, a deeper swelling within the deep dermis, subcutaneous tissue and/or mucous membranes.

Although angioedema can occur anywhere, it characteristically involves the periocular skin, the lips and/or the genitalia. Its resolution is typically slower than wheals (hives), lasting up to 72 hours.1

Aetiology

Types of urticaria

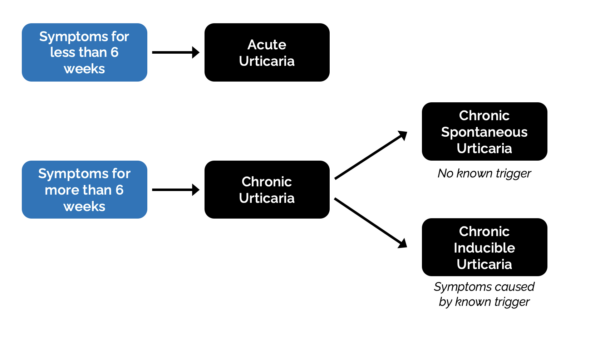

Urticaria can be broadly classified into acute and chronic:

- Acute urticaria: sudden onset of wheals, at times associated with triggers such as infection or medication. It is often self-limiting, with symptoms resolving within a few hours to days. In total, it lasts up to 6 weeks.

- Chronic urticaria: Persistent or recurrent wheals lasting for more than six weeks. Chronic urticaria can be spontaneous (idiopathic) or inducible (caused by a known trigger).

Pathophysiology

Urticaria is predominantly a mast cell driven disease. Mast cells are activated by various signals (including autoantibodies and cytokines) and release histamine.

Histamine causes an increase in the permeability of local capillaries and small venules. The increased permeability results in oedema of the upper and mid-dermis, giving the typical itchy, red-raised wheel appearance in urticaria.1

Urticaria is commonly idiopathic, meaning it has no specific identifiable cause.

Inducible urticaria, on the other hand, occurs only when a trigger is present (Table 1).

Table 1. Triggers for chronic inducible urticaria.1

| Subtype | Trigger identified |

| Aquagenic urticaria | Exposure to water, be it hot or cold |

| Cholinergic urticaria | Active or passive warming (e.g. from exercise or emotional upset) |

| Cold urticaria | Exposure of skin to cold (such as swimming in cold water) |

| Heat urticaria | Exposure of skin to a heat source |

| Symptomatic dermatographism | Shearing force acting on the skin |

| Delayed pressure urticaria | Sustained pressure (e.g. after sitting or lying, or due to tight clothing) |

| Solar urticaria | Exposure to UV radiation |

| Vibratory angioedema | Exposure to vibratory stimuli (such as use of power tools) |

| Contact urticaria | Skin contact with an offending agent |

However, some patients with spontaneous urticaria report trigger-induced wheals or angioedema. Triggers can include NSAIDs, aspirin, tight clothing, heat or a particular food item. These triggers are, however, not definite because signs and symptoms can occur in the absence of such triggers, and their presence may not always induce signs and symptoms of urticaria.

Risk factors

Urticaria can occur in the absence of risk factors. However, risk factors that can predispose an individual to an increased risk of urticaria can include:3,4

- Female sex

- Age between 20 – 40

- Atopy

- Chronic stress

- Family history

Clinical features

Urticaria causes highly pruritic raised skin rash with lesions that may be round or ring-shaped.

Lesions often become confluent. Each lesion can last between a few minutes and up to 24 hours before resolving completely. The diagnosis of urticaria is clinical, based on the history and appearance of the rash.

In active urticaria, a typical urticarial rash will have three main features:1

- Central raised swelling of variable size and shape surrounded by an area of erythema

- Associated pruritus

- A fleeting nature where they can appear and disappear quickly, usually within 1-24 hours

History

Important areas to cover in the history include:

- Time of onset

- Nature, duration, pattern and frequency of the rash

- The presence of itching (typically, pruritus is stimulated by skin contact and patients can complain that scratching will increase the itchiness of the rash)

- Possible triggers or causes (to determine if the condition is spontaneous or inducible)

Clinical examination

Due to the fleeting nature of the rash, it is not uncommon for patients to have no clinical signs on examination.

Patients may bring photos of their rash, which can help make the diagnosis. Urticarial rashes are seen as raised swellings of variable size and shape surrounded by erythema.

Inducible urticaria can be confirmed by provocation testing. For example, applying a sufficiently firm stroke on the back of the patient may reveal dermatographism, which is seen as a linear wheal and flare within a few minutes of application of the stimulus.8

Differential diagnoses

Urticaria is often a straightforward diagnosis, but differential diagnoses which may be considered include:

- Scombroid fish poisoning

- Urticarial vasculitis

- Hereditary angioedema

- Pre-bullous stage of bullous pemphigoid

Investigations

Acute urticaria is self-limiting, and therefore, investigations are not usually required.

In chronic urticaria, no investigations are routinely required. A full blood count and ESR can be considered, which may be abnormal in urticarial vasculitis and autoinflammatory syndromes.

In chronic inducible urticaria, provocation testing may be performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Patch testing

Patch testing is unsuitable for investigating urticaria, as it is designed to detect type 4 delayed cell-mediated eczematous hypersensitivity reactions. In contrast, urticaria typically results from type 1 hypersensitivity reactions, which are immediate and involve IgE antibodies and mast cells.

Management

Management aims to control symptoms to achieve a normal quality of life and prevent recurrence.

Lifestyle modifications

In spontaneous urticaria, lifestyle modifications should focus on avoidance of aggravating factors such as NSAIDs, heat, and tight clothing. Cooling the skin, for example, using a cold flannel or a moisturising lotion may further help to ease symptoms.

In inducible urticaria (where there is an identified trigger), lifestyle modifications focus on avoiding the specific trigger:1

- Symptomatic dermographism: reduce friction and avoid tight clothing

- Cold urticaria: dress warmly in cold or windy conditions and avoid swimming in cold water

- Delayed pressure urticaria: broaden the contact area, for example, of a heavy bag or using a seatbelt cushioned cover

- Solar urticaria: wear long-sleeved clothing, avoid peak sun hours and apply broad-spectrum sunscreens

Medical management

Oral second‐generation (non-sedating) H1‐ antihistamines are used as the first and second-line treatment in urticaria. Examples include cetirizine, levocetirizine, desloratadine, and fexofenadine.1,9

Start at a standard dose of one tablet daily in adults and reassess every 2-4 weeks (first-line). If the response is inadequate, the dose can be increased fourfold (second-line).

One type of antihistamine can be switched to another if there is a poor response or the medication is not tolerated.

A short course (up to 10 days) of oral prednisolone can be added for symptom control in severe urticarial flares.9,10 Long-term steroids are not recommended. Topical steroids are of no use.

If symptoms do not settle with antihistamines, the patient should be referred appropriately for specialist care.

Specialist treatments

Further treatment escalation should only be initiated by a specialist.

Examples of such treatment can include omalizumab (anti-IgE monoclonal antibody) and ciclosporin (calcineurin inhibitor).9

Validated tools such as the Urticaria activity score (UAS) or the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) can help monitor disease activity and assess the effectiveness of ongoing treatment.11,12

Complications

Urticaria can greatly affect patients’ quality of life. The discomfort, itching, and unpredictability of flare-ups have an impact on both the daily activities and emotional well-being of patients’ lives.

Urticarial symptoms, especially pruritus, can disrupt sleep, be a source of anxiety or depression and can interfere with performance at work or school.

Prognosis

The prognosis for urticaria is generally good, especially with appropriate management. Many are self-limiting or respond well to treatment. However, a minority of chronic cases require long-term treatment.

Key points

- Urticaria is typically spontaneous, often having no obvious cause. The pathophysiology involves histamine released from mast cells.

- It can be acute (<6 weeks) or chronic (>6 weeks).

- Urticarial lesions (wheals) are transient and move about, typically found on areas of pressure such as trunk, extremities and ears, lasting less than 24 hours, and resolving without a trace.

- If lesions persist longer than 24 hours or leave marks behind, an alternative diagnosis, such as urticarial vasculitis, should be considered.

- Angioedema can accompany urticaria, in which case one should assess airway patency.

- Second-generation H1-antihistamines are first-line treatments, where up to fourfold of the standard dose can be used. Omalizumab or Ciclosporin are used in refractory cases.

- Long-term systemic steroids are not recommended, but a short-term rescue dose can sometimes be prescribed in severe urticarial flares.

Reviewer

Dr Daniel Micallef

Dermatology registrar

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Urticaria. Published in 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- Dermnet. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Classification of Urticaria. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Sánchez-Borges, M., Ansotegui, I. J., Baiardini, I., et al. The challenges of chronic urticaria part 1: Epidemiology, immunopathogenesis, comorbidities, quality of life, and management. Published in 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- Hon, K. L., Leung, A. K. C., Ng, W. G. G. and & Loo, S. K. (2019) Chronic Urticaria: An Overview of Treatment and Recent Patents. Published in 2019. Available From: [LINK]

- Dermnet. Urticarial rash dark skin. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Dermnet. Typical Urticarial lesion. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Dermnet. Urticarial lesion on trunk. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Nobles, T., Muse, M. E., & Schmieder, G. J. Published in 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- Sabroe, R.A., Lawlor, F., Grattan, C.E.H., Ardern‐Jones, M.R., Bewley, A., Campbell, L., Flohr, C., Leslie, T.A., Marsland, A.M., Ogg, G., Sewell, W.A.C., Hashme, M., Exton, L.S., Mohd Mustapa, M.F. and Ezejimofor, M.C. (2021). British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for the management of people with chronic urticaria. Published in 2021. Available from: [LINK].

- Dermnet. Urticaria – an overview. 2021 Available at: [LINK]

- MDcalc. Urticaria severity score. Available at: [LINK]

- AY Finlay, GK Khan. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)–a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Published in 1992. Available from: [LINK]