- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common type of cancer in the world.1 It is a non-melanoma form of skin cancer that develops very slowly in the upper layers of the skin and rarely metastasises.

The incidence of BCC is higher in areas with low geographic latitude (with Australia being the country with the highest incidence of the disease) and people with low pigment status.2

Recently, a rapid increase in the incidence of BCC has been noted in Western countries, most likely attributed to the ageing population and artificial exposure to UV radiation, from an early age.3

Aetiology

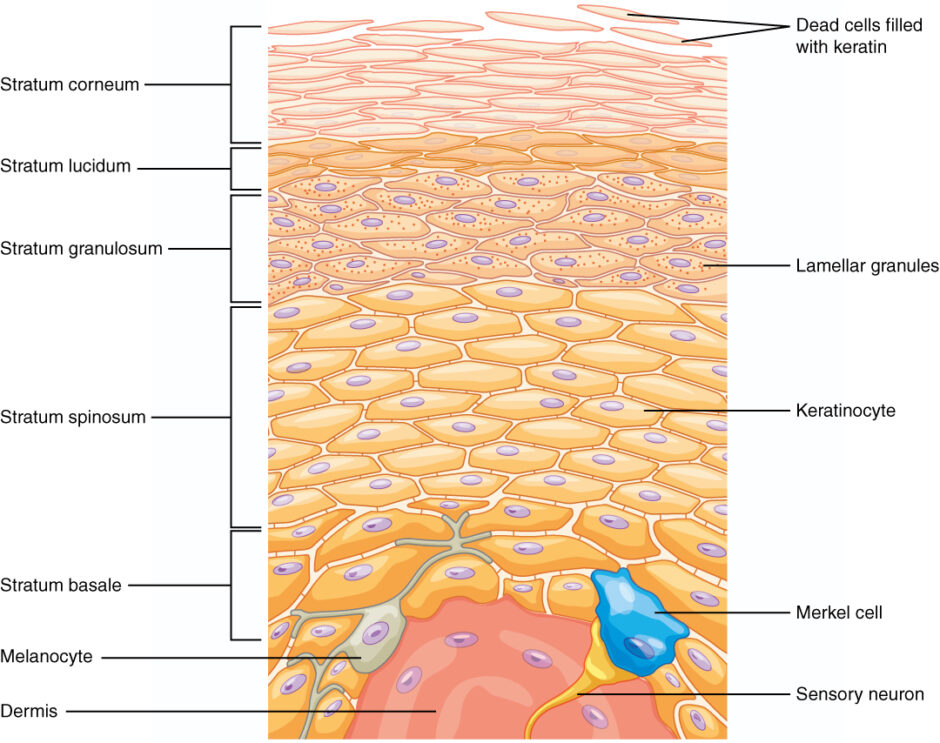

The skin consists of three layers:4,5

- The epidermis: the thin outer portion of the skin made up of the inner basal layer, the prickle cell layer, the granule cell layer and the keratinised squamous layer (Figure 1)

- The dermis: the thicker inner portion of the skin which consists of connective tissue and contains nerves, vessels and sweat glands

- The hypodermis: the innermost layer that fuses with the dermis and consists of adipose tissue and sweat glands

BCCs develop from mutations, usually in the PTCH and TP53 genes, affecting the basal cell layer of the epidermis.

Risk factors

Risk factors for the development of BCC include:6,7,8,9

- Exposure to UV radiation, especially acute intermittent exposure at a young age

- Fair skin prone to sunburn that does not tan easily

- Ionising radiation

- Repeated micro-injuries

- Scars/chronic ulcers

- Prolonged exposure to chemical agents (i.e. arsenic)

- Gorlin syndrome

- Immunosuppression

- History of skin cancer

Clinical features

Most BCCs occur in sun-exposed areas, commonly on the face. BCCs develop very slowly and rarely metastasise. Local invasion is the most common mechanism of spread. They are usually asymptomatic but can present with pruritus or mild discomfort.

Clinically, BCCs can be categorised into three main types: nodular, superficial and morpheaform.

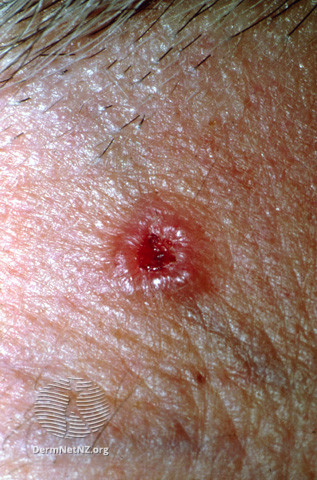

Nodular BCC

Nodular BCC is the most common type and usually presents on the head (eyelids, cheeks, forehead). Nodular BCCs clinically appear as pearly, shiny papules or nodules with small arborising telangiectasias, rolled borders and sometimes a depressed centre. Lesions are very sensitive and may bleed on minor trauma.10

Superficial BCC

Superficial BCC is the second most common type of BCC and usually presents as a plaque or patch of well-defined, scaly, pink skin. Some superficial BCCs may be pigmented. Superficial BCCs occur most commonly on the trunk and extremities and in younger patients.10,11

Morpheaform BCC

Also referred to as sclerosing or infiltrating BCC, morpheaform BCC is the least common type of BCC. This presents as a poorly defined, pale scar or indurated plaque. Its spread is very subtle. Therefore this type of BCC has the poorest prognosis since it can subclinically destroy surrounding tissue.10

Pigmented BCCs

Less frequently, various amounts of melanin might be present in a BCC, which is then referred to as pigmented. The differentiation between pigmented BCC and melanoma is challenging.

Clinical examination

A thorough clinical examination is required to identify characteristic BCC features and aid diagnosis. For more information, see the Geeky Medics guides to examining a non-pigmented skin lesion and pigmented skin lesion.

Dermatoscopy involves examining skin lesions with a dermatoscope, a magnifying tool that utilises polarised light. With dermatoscopy, diagnostic features of a BCC not visible to the naked eye (e.g. telangiectasias, microulcerations or globules) are easily identified.11

Differential diagnoses

Differential diagnoses vary depending on the type of BCC:

- Nodular: molluscum contagiosum, amelanotic melanoma, fibrous papule

- Superficial: inflammatory skin diseases such as psoriasis, lichenoid keratosis, actinic keratosis, Bowen’s disease

- Morpheaform: scar, localised scleroderma (morphea), Merkel cell carcinoma, amelanotic melanoma

Investigations

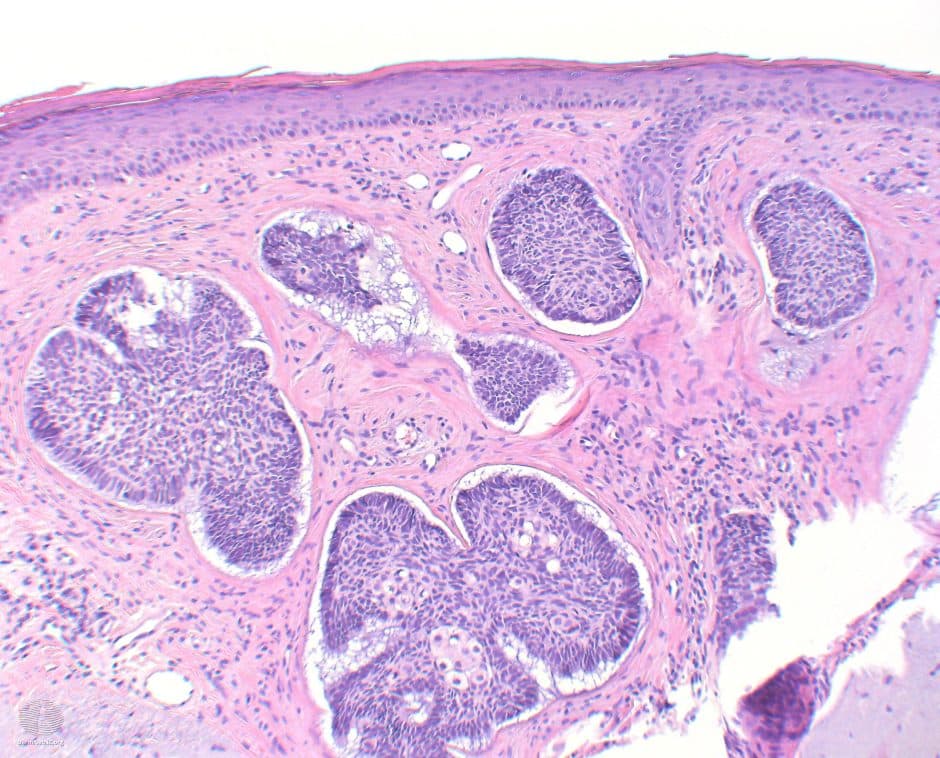

The definitive diagnosis of a BCC requires a biopsy and histopathological examination.

A biopsy can be excisional, incisional, shave, or punch, with the latter having the lowest diagnostic accuracy.13

Nodular and superficial BCCs are considered low-risk, whereas morpheaform is high-risk due to their extensive local spread and high recurrence rate.

Common histologic features of all BCCs include:14

- Basophilic aggregations of basaloid keratinocytes with large nuclei and scant cytoplasm

- Clefts of tumour tissue

- Peripheral palisading of nuclei

- Apoptotic cells

Management

Recurrence-free treatment rates of BCC are high, up to 95%, with early diagnosis and management. The main goal of treatment is the complete removal of the tumour with preservation of the function and cosmesis of the affected area. The type of treatment depends on whether the BCC is low or high risk.15

Low-risk BCCs are usually treated with complete surgical removal or electrodesiccation and curettage (ED&C). Other treatment options for low-risk BCC include topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), cryotherapy and photodynamic therapy.

Mohs micrographic surgery is a specialist removal method for non-melanoma skin cancers with high recurrence risk. It has the advantage of preserving as much surrounding skin as possible. As an alternative for high-risk lesions, simple resection with adjunct radiotherapy has been recommended.16,17,18

The clinical diagnosis of BCC is sometimes challenging. In this case, a referral to a specialist dermatologist or oculoplastic ophthalmologist is recommended to confirm the diagnosis with a biopsy. This ensures that atypical squamous cell carcinomas and melanomas, which might imitate BCCs, are appropriately detected and treated.

Complications

Complications of basal cell carcinomas include:19

- Recurrence

- Increased risk of developing other types of skin cancer, including melanoma

- Disfiguration, if left untreated

- Aggressive forms of skin cancer can invade and destroy bones, nerves and muscles

- Metastasis in rare cases

Key points

- Basal cell carcinoma is a form of non-melanoma skin cancer and is the most common cancer worldwide

- An important risk factor is exposure to UV radiation

- The most common type of BCC is nodular, which mainly affects the face and presents as pearly lesions with rolled borders

- Other types of BCC include superficial, morpheaform and pigmented BCCs

- Definitive diagnosis of a BCC requires a biopsy and histopathological examination

- Management options include surgical excision, ED&C, topical treatments, cryotherapy and photodynamic therapy

- Complications include recurrence, increased risk of other forms of skin cancer, disfiguration and metastasis (rare)

Reviewer

Anna Gkountelia

Consultant Oculoplastic Ophthalmologist

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Rogers H.W., Weinstock M.A., Feldman S.R., Coldiron B.M. Incidence Estimate of Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer (Keratinocyte Carcinomas) in the US Population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081.

- Verkouteren J.A.C., Ramdas K.H.R., Wakkee M., Nijsten T. Epidemiology of basal cell carcinoma: Scholarly review. Br. J. Dermatol. 2017;177:359–372.

- Teng Y, Yu Y, Li S, Huang Y, Xu D, Tao X, Fan Y. Ultraviolet Radiation and Basal Cell Carcinoma: An Environmental Perspective. Front Public Health. 2021 Jul 22;9:666528.

- Marghoob AA. Skin cancers and their etiologies. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2011 Dec;30(4 Suppl):S1-5.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015 Jun 1;88(2):167-79.

- Karagas MR, McDonald JA, Greenberg ER, Stukel TA, Weiss JE, Baron JA. et al. Risk of basal cell and squamous cell skin cancers after ionizing radiation therapy. For The Skin Cancer Prevention Study Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88(24):1848–1853.

- Karagas MR, Tosteson TD, Blum J, Morris JS, Baron JA, Klaue B. Design of an epidemiologic study of drinking water arsenic exposure and skin and bladder cancer risk in a U.S. population. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106 Suppl 4:1047–1050.

- Euvrard S, Kanitakis J, Claudy A. Skin cancers after organ transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(17):1681–1691.

- Spadari F, Pulicari F, Pellegrini M, Scribante A, Garagiola U. Multidisciplinary approach to Gorlin-Goltz syndrome: from diagnosis to surgical treatment of jawbones. Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022 Jul 18;44(1):25.

- Scrivener Y, Grosshans E, Cribier B. Variations of basal cell carcinomas according to gender, age, location and histopathological subtype. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147(1):41–47.

- McCormack CJ, Kelly JW, Dorevitch AP. Differences in age and body site distribution of the histological subtypes of basal cell carcinoma. A possible indicator of differing causes. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133(5):593–596.

- Altamura D, Menzies SW, Argenziano G, Zalaudek I, Soyer HP, Sera F. et al. Dermatoscopy of basal cell carcinoma: morphologic variability of global and local features and accuracy of diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(1):67–75.

- Haws AL, Rojano R, Tahan SR, Phung TL. Accuracy of biopsy sampling for subtyping basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(1):106–111.

- Sexton M, Jones DB, Maloney ME. Histologic pattern analysis of basal cell carcinoma. Study of a series of 1039 consecutive neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(6 Pt 1):1118–1126.

- Silverman MK, Kopf AW, Bart RS, Grin CM, Levenstein MS. Recurrence rates of treated basal cell carcinomas. Part 3: Surgical excision. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18(6):471–476.

- Miller SJ, Alam M, Andersen J, Berg D, Bichakjian CK, Bowen G. et al. Basal cell and squamous cell skin cancers. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8(8):836–864.

- Neville JA, Welch E, Leffell DJ. Management of nonmelanoma skin cancer in 2007. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4(8):462–469.

- Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL Jr.. Mohs surgery is the treatment of choice for recurrent (previously treated) basal cell carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15(4):424–431.

- Fagan J, Brooks J, Ramsey ML. Basal Cell Cancer. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; August 20, 2022.

Image references

- Figure 1. OpenStax. Layers of the epidermis. License: [CC BY]

- Figure 2. DermNet. Nodular basal cell carcinoma. License: [CC BY-NC-ND]

- Figure 3. DermNet. Superficial basal cell carcinoma. License: [CC BY-NC-ND]

- Figure 4. DermNet. Morphoeic basal cell carcinoma. License: [CC BY-NC-ND]

- Figure 5. DermNet. Pigmented basal cell carcinoma. License: [CC BY-NC-ND]

- Figure 5. DermNet. Basal cell carcinoma pathology. License: [CC BY-NC-ND]