- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

This guide provides an overview of the stages of wound healing.

The skin’s natural barrier to the external environment is provided by two distinct layers, the epidermis (surface) and the dermis (slightly deeper).

When the epidermis +/- dermis are damaged, this protective barrier becomes compromised and the body initiates a sequential repair process in response.

The wound healing process involves the following key stages:

- Haemostasis

- Inflammation

- Cell proliferation

- Epithelialisation

- Tissue remodelling

Haemostasis phase

The process of haemostasis is initiated within seconds of injury to the skin via vasoconstriction thus reducing the potential for significant blood loss.

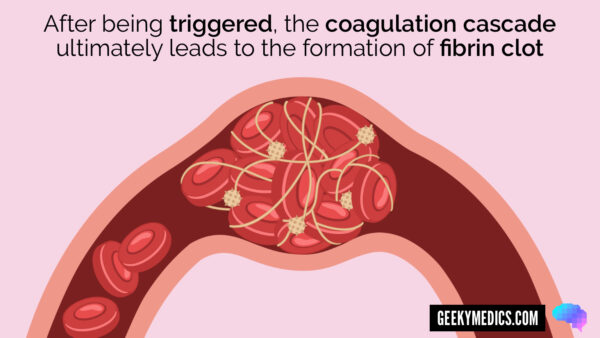

Then, as blood leaks into the open wound, platelets are exposed to collagen, which triggers the coagulation cascade, ultimately resulting in the formation of a fibrin clot. Clot formation prevents further bleeding from the damaged blood vessels within the tissue.

Inflammation phase

The inflammation phase lasts approximately 3 days.

As well as triggering the coagulation cascade, platelets also release growth factors which attract neutrophils, macrophages, monocytes, fibroblasts and other cell types which are required for effective wound healing.

Once within the wound, neutrophils ingest bacteria and debris via phagocytosis, helping to clean the wound. The pus commonly observed at this stage of wound healing represents large numbers of neutrophils filled with debris and bacteria.

During the inflammation stage, blood vessels within the wound also become more permeable due to the release of prostaglandins and histamine. Serous fluid leaks through the permeable blood vessel walls into the wound and surrounding tissue, causing oedema.

Neutrophils slowly undergo apoptosis (programmed cell death) over the following 2-3 days. Monocytes then become activated and turn into wound macrophages to further facilitate wound cleansing by mopping up the neutrophils and debris via phagocytosis and attracting other cell types that are key to wound healing including fibroblasts, vascular endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells.

The primary aims of the inflammation phase are to maintain control of blood loss and the cleanliness of the wound bed.

Proliferation phase

The proliferative phase involves the production of highly vascular granulation tissue (a form of connective tissue) which fills the wound and provides a scaffold for further healing.

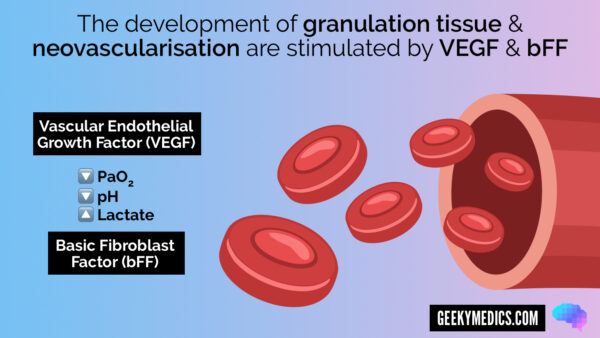

The proliferative process is triggered by an environment of low wound pH, reduced PaO2 and increased lactate (due to reduced blood supply to the wound).

This environment stimulates the release of several growth factors including but not limited to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and basic fibroblast factor (bFF). These growth factors help to drive neovascularisation and angiogenesis within the wound.

As new blood vessels form, the blood supply to the tissue within the wound improves, oxygen tension within the wound subsequently increases and VEGF is inhibited through negative feedback. Fibroblasts also begin to produce collagen to replace the original extracellular matrix scaffold that is formed at the beginning of the proliferative phase.

Contraction

Contraction occurs in the context of open wounds to assist the healing process, as it results in a smaller deficit to be filled with connective tissue. The underlying process of contraction is still poorly understood, but it likely involves contractile forces generated by fibroblasts within the wound.

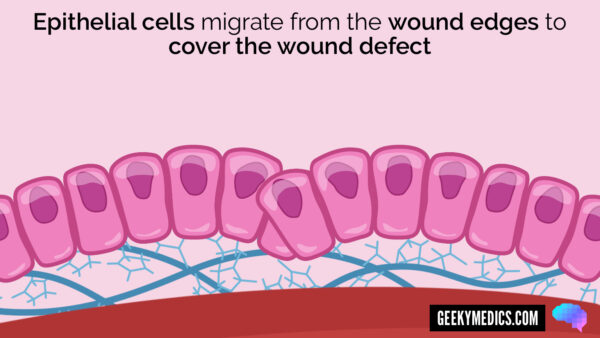

Epithelialisation phase

Epithelial cells migrate from the wound edges to cover the wound defect. This only occurs once the wound has been filled with granulation tissue, in the context of wound healing by secondary intention. Epithelial cells require a moist, well-vascularised wound surface to migrate across the tissue. As a result, if the wound is dry or necrotic, epithelialisation will not occur.

Re-modelling phase

The re-modelling phase involves the iterative breakdown and rebuilding of the wound’s extracellular matrix by matrix metalloproteinases.

This process is slow, often lasting more than a year and assists with gradual improvement in the tensile strength of the wound. The tensile strength of scar tissue, even after multiple rounds of remodelling, will never reach that of healthy unwounded tissue (max 80%).

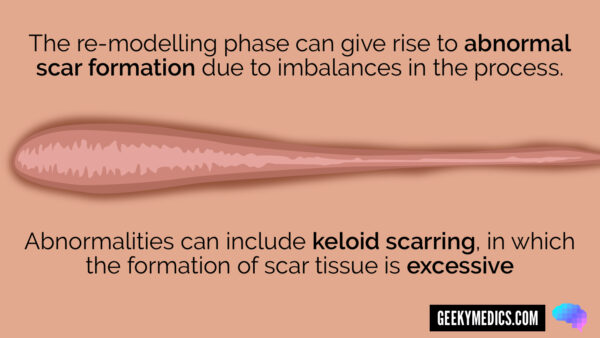

The remodelling phase can sometimes give rise to abnormal scar formation due to imbalances in the process. Abnormalities can include hypertrophic scarring (a.k.a. keloid scarring) in which the formation of scar tissue is excessive resulting in raised areas of scar tissue.

References

- Pauline Beldon. Basic science of wound healing. Surgery (Oxford). Volume 28, Issue 9, 2010, Pages 409-412, ISSN 0263-9319.

- Htirgan. Adapted by Geeky Medics. License: [CC BY-SA]