- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis refers to acute inflammation of the pancreas.1

In the United Kingdom, the prevalence of pancreatitis is around 56 cases per 100,000 annually.2

Though it is mild in most people (mortality <1%), patients can deteriorate quickly. There is a high mortality rate (~15%) in patients with severe pancreatitis.

Aetiology

Anatomy

The pancreas is a soft, spongy, lobulated organ that sits in the upper part of the retroperitoneal space of the abdomen.

The pancreas has four parts:

- a head,which sits in the C-shaped cavity created by the duodenum, and usually has a small uncinate process which hooks upwards behind the superior mesenteric artery and superior mesenteric vein

- the constricted neck connects the head to the body, behind this the portal vein forms from the union of the splenic and superior mesenteric veins

- the body runs upwards and to the left across the midline

- the tail travels with the splenic vessels between the layers of the splenorenal ligament, to reach the hilum of the spleen

The pancreas functions as both an exocrine and an endocrine gland.

The exocrine pancreas consists of acinar and ductal cells which produce 750-1000ml of pancreatic juice per day. This is secreted into the duodenum via the pancreatic duct and aids the processes of digestion and absorption of food.

The endocrine pancreas consists of tiny clusters of endocrine cells called the islets of Langerhans which are embedded throughout the pancreatic tissue. There are several different cell types which release specific hormones into the bloodstream via capillaries and play an essential role in regulating glucose homeostasis and gut function.

Pathophysiology

The inflammation in acute pancreatitis is typically caused by hypersecretion or backflow (due to obstruction) of exocrine digestive enzymes, which results in autodigestion of the pancreas.

Pancreatic damage can be classified into two major categories:1

- Interstitial oedematous pancreatitis: most common, better prognosis

- Necrotising pancreatitis: less common, around 5-10%, more severe

The damage that occurs during acute pancreatitis is potentially reversible (to varying degrees), whereas chronic pancreatitis involves ongoing inflammation of the pancreas that results in irreversible damage.

Chronic pancreatitis is associated with endocrine and exocrine dysfunction, as well as chronic abdominal pain.

Causes of pancreatitis

Most cases of pancreatitis in the UK are caused by gallstones or alcohol.

A commonly used mnemonic to help remember the less common causes is I GET SMASHED:

- Idiopathic

- Gallstones

- Ethanol

- Trauma

- Steroids

- Mumps/malignancy

- Autoimmune disease

- Scorpion sting

- Hypertriglyceridemia/Hypercalcaemia

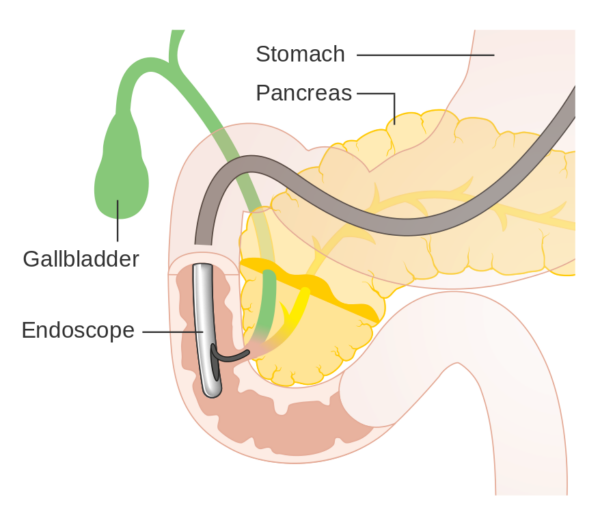

- ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography)

- Drugs: commonly azathioprine, thiazides, septrin, tetracyclines

Risk factors

Risk factors for pancreatitis include:

- Male gender

- Increasing age

- Obesity

- Smoking

Clinical features

History

Typical symptoms of acute pancreatitis include:

- Epigastric pain: typically severe, sudden onset and may radiate through to the back

- Nausea and vomiting

- Decreased appetite

Other important areas to cover in the history include:

- Past medical history: history of gallstones, biliary disease or previous episodes of pancreatitis

- Past surgical history: recent surgical procedures (e.g. ERCP)

- Drug history: regular medications and over the counter medications

- Social history: alcohol intake and smoking

- Family history: hereditary pancreatitis is a rare cause of pancreatitis

Clinical examination

A thorough abdominal examination should be performed on all patients with suspected acute pancreatitis.

Typical clinical findings may include:

- Epigastric tenderness

- Abdominal distention: due to local reactive ileus or retroperitoneal fluid

- Reduced bowel sounds: if an ileus has developed

- Evidence of a systemic inflammatory response: indicative of severe pancreatitis. If febrile and hypotensive on admission the patient is more likely to develop organ failure during their hospital stay. Tachycardia is a less helpful sign, as the adrenergic response can be driven by pain and stress.

Cullen’s and Grey Turner’s sign

Cullen’s sign (peri-umbilical bruising) and Grey-Turner’s sign (flank bruising) are important to be aware of, but these are late signs of severe intra-abdominal and retroperitoneal haemorrhage, respectively.

Diagnosis

The International Association of Pancreatology criteria state that two of three criteria must be satisfied for a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis to be made:4

- Abdominal pain plus a history suggestive of acute pancreatitis

- Serum amylase/lipase of over three times the upper limit of normal

- Imaging findings characteristic of acute pancreatitis

Classification of acute pancreatitis

Classification of acute pancreatitis is governed by the Atlanta Criteria:7

- Mild: most common, no organ dysfunction/complications, resolves normally within a week

- Moderate: initially some evidence of organ failure which improves within 48 hours

- Severe: persistent organ dysfunction for greater than 48 hours, together with local or systemic complications

Differential diagnoses

Severe, sudden onset epigastric pain has several other serious causes. These include:

- Leaking abdominal aortic aneurysm

- Aortic dissection

- Myocardial infarction

- Perforated gastric/duodenal ulcer

- Oesophageal rupture

Imaging (e.g. CT) is often required to rule out alternate pathology.

Investigations

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations include:

- ECG: a baseline investigation that should be performed for all patients presenting with epigastric pain (to avoid missing the myocardial infarction masquerading as epigastric pain)

- Urinalysis: a routine investigation in acute abdominal pain (however, the urological system is unlikely to be the cause of sudden onset epigastric pain)

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:5

- FBC: anaemia (may increase cardiovascular strain), raised WCC (part of the SIRS response)

- CRP: non-specific, however elevated levels at admission can be used as an indicator of severity

- U&Es: fluid depletion is extremely common in pancreatitis, so pay close attention to urea and creatinine

- LFTs: may be deranged, more commonly (but not exclusively) in obstructive causes of pancreatitis (e.g. gallstone disease)

- Lipase: very specific, normally 15-60 U/L, greater than three or more times the upper limit of normal is highly suggestive of pancreatitis

- Serum amylase: three or more times normal is suggestive of pancreatitis (less specific than lipase)

- Venous blood gas (VBG): rapid method to assess pH, electrolytes, Hb and lactate

- Arterial blood gas (ABG): essential for prognostic scoring in acute pancreatitis, provides a more accurate acid-base balance and true PaO2/CO2 (compared to a VBG)

- beta-hCG: should be checked in all women of childbearing age, not only to rule out ectopic pregnancy but also to permit investigations such as x-ray and CT safely

Imaging

As mentioned previously, the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis can and should be made clinically, however, imaging is sometimes used to support the diagnosis or rule out other pathology.

Relevant imaging investigations include:6

- Erect chest X-ray: used to look for free gas under the diaphragm (pneumoperitoneum) in patients who present with epigastric tenderness.

- Abdominal ultrasound (USS): a useful investigation to assess the biliary tree for evidence of obstruction (e.g. biliary dilatation). The pancreas can sometimes be assessed using abdominal USS (e.g. evidence of oedema may be noted), however, the presence of bowel gas often obscures the pancreas, making assessment difficult or impossible.

- CT abdomen and pelvis (CT-AP): used to exclude other causes of severe abdominal pain and assess for complications of pancreatitis (e.g. pseudocyst formation). CT-AP provides optimum imaging of the pancreas and is typically performed at 48-72 hours after the initial presentation if patients do not clinically improve (to assess for evidence of pancreatic necrosis or other complications)

Prognostication of pancreatitis

Various tools exist for the prognostication of acute pancreatitis, with each aiming to identify those at higher risk of acute deterioration.

Glasgow-Imrie score8

The Glasglow-Imrie score is used to assess the severity of acute pancreatitis. This severity score can be easily remembered using the mnemonic PANCREAS. Each criterion met, gets one point, and severe pancreatitis is indicated by a score of 3 or more:

- PaO2 <7.9

- Age >55

- Neutrophils (really WCC) >15

- Calcium <2.0

- Renal function: urea >16mmol/L

- Enzymes: LDH >600 IU/L

- Albumin <32 g/L

- Sugar >10mmol

Ranson’s criteria10

Ranson’s criteria is used to predict mortality from pancreatitis. It uses a smaller range of clinical and biochemical markers; first at admission then again at 48 hours, to generate a predictive score of mortality.

Management

An ABCDE approach should be taken for all patients with acute pancreatitis.

Immediate management

Immediate management of acute pancreatitis should include:12

- Intravenous fluid resuscitation and correction of electrolyte disturbances

- Analgesia: intravenous paracetamol and opioids

- Antiemetics

- Nil by mouth: until initial pain improves

- Control of blood glucose

Current evidence suggests that routine antibiotic use for acute pancreatitis does not provide any benefit to patients and therefore should be avoided. In the context of pancreatic necrosis, antibiotics are often used prophylactically due to the increased risk of infection.

Nutrition

Patients should be nil by mouth (NBM) until initial pain improves (with gradual re-introduction of feeding via the oral route)

If the oral route is not tolerated, consider nasojejunal (NJ) feeding. If enteral feeding is not possible, total parenteral nutrition (TPN) should be considered in people with ongoing lack of nutrition, though enteral feeding is associated with better outcomes.

Specific management of the underlying cause

The two most common causes of acute pancreatitis are gallstone disease and alcohol excess.

Gallstone pancreatitis

Specific management of gallstone pancreatitis may include:13,14

- Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): to relieve biliary obstruction, with or without sphincterotomy to dilate the sphincter of Oddi. This allows ductal stones to be removed, biliary sludge to be cleared, and relief of the obstructed biliary tree driving pancreatitis.

- Cholecystectomy: should be performed on all patients with gallstone pancreatitis during the same admission as the acute episode. Delay is associated with a high chance of disease recurrence and readmission. The bile duct should be explored during this procedure to rule out ductal stones.

Alcohol-induced pancreatitis

Patients withdrawing from alcohol should be managed according to severity scores, for example, the CIWA score. The general principles are:

- Benzodiazepines to treat withdrawal agitation and seizures

- Thiamine, folate, and vitamin B12 replacement

Complications

Early complications

Early complications of acute pancreatitis include:16

- Necrotising pancreatitis

- Infected pancreatic necrosis: occurs when necrosing pancreatic tissue becomes infected, patients require antibiotics and necrosectomy

- Pancreatic abscess: occurs when peripancreatic collections of fluid become infected, urgent drainage is required

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): associated with the SIRS response of acute pancreatitis. Typical CXR appearance of widespread bilateral pulmonary infiltrates

Late complications

Late complications of acute pancreatitis include:17

- Pancreatic pseudocysts: collections of fluid that are not surrounded by epithelium. They are typically amylase-rich and can become infected, rupture or bleed. Pseudocysts typically accumulate within four weeks after acute pancreatitis. Only 40% resolve spontaneously, therefore intervention is usually advised (drainage/excision).

- Portal vein/splenic thrombosis: secondary to ongoing inflammation, anticoagulation required

- Chronic pancreatitis: repeated attacks of acute pancreatitis can lead to ongoing inflammation and fibrosis of the pancreas

- Pancreatic insufficiency: the exocrine function of the pancreas is more commonly affected (whilst the endocrine function is typically maintained).

Key points

- Acute pancreatitis refers to acute inflammation of the pancreas.

- The pancreas is a soft, spongy, lobulated organ which sits in the upper part of the retroperitoneal space of the abdomen. It has endocrine and exocrine functions.

- The inflammation in acute pancreatitis is typically caused by hypersecretion or backflow (due to obstruction) of exocrine digestive enzymes, which results in autodigestion of the pancreas.

- Most cases of pancreatitis in the UK are caused by gallstones or alcohol.

- Typical symptoms of acute pancreatitis include sudden onset epigastric pain, nausea & vomiting and anorexia.

- Typical clinical findings may include epigastric tenderness, abdominal distension and evidence of a systemic inflammatory response

- The diagnosis of acute pancreatitis can and should be made clinically, however, imaging is sometimes used to support the diagnosis or rule out other pathology.

- Various tools exist for the prognostication of acute pancreatitis, with each aiming to identify those at higher risk of acute deterioration. Examples include the Glasgow-Imrie score and Ranson’s criteria.

- General management of pancreatitis is supportive with intravenous fluids, analgesia, antiemetics and nutritional support.

- Specific management depends on the underlying cause of pancreatitis. Patients with biliary obstruction often require an ERCP.

Reviewer

Mr Martyn Stott

Hepatobiliary Registrar

Editor

Hannah Thomas

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- International Pancreatic Association/American Pancreatic Association. Evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Published in 2013. Available from: [LINK]

- BMJ Best Practice. Acute Pancreatitis. Last updated in 2013. Available from: [LINK]

- Van Brummelen SE et al. Acute idiopathic pancreatitis: does it really exist or is it a myth? Published in 2003. Available from: [LINK]

- International Pancreatic Association/American Pancreatic Association. Evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Published in 2013. Available from: [LINK]

- Rompianesi G et al. Serum amylase and lipase and urinary trypsinogen and amylase for diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. Published in 2017. Available from: [LINK]

- Balthazar EJ et al. Acute pancreatitis: value of CT in establishing prognosis. Published in 1990. Available from: [LINK]

- Banks PA et al; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis – 2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Published in 2013. Available from: [LINK]

- Imrie CW et al. A single-centre double-blind trial of Trasylol therapy in primary acute pancreatitis. Published in 1978. Available from: [LINK]

- Knaus WA et al. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Published in 1985. Available from: [LINK]

- Ranson JH, Rifkind KM, Turner JW. Prognostic signs and nonoperative peritoneal lavage in acute pancreatitis. Published in 1976. Available from: [LINK]

- Balthazar EJ et al. Acute pancreatitis: value of CT in establishing prognosis. Published in 1990. Available from: [LINK]

- BMJ Best Practice. Acute Pancreatitis. Last updated in 2013. Available from: [LINK]

- Kimura Y. JPN Guidelines 2010. Gallstone-induced acute pancreatitis. Published in 2010. Available from: [LINK]

- BMJ Best Practice. Acute Pancreatitis. Last updated in 2013. Available from: [LINK]

- International Pancreatic Association/American Pancreatic Association. Evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Published in 2013. Available from: [LINK]

- Way LW, Doherty GM. Chapter 27: Pancreas. In: Current surgical diagnosis & treatment. Published in 2003. Available from: [LINK]

- BMJ Best Practice. Acute Pancreatitis. Last updated in 2013. Available from: [LINK]

Image references

- Figure 1. OpenStax. Pancreas. License: [CC-BY]

- Figure 2A. Herbert L. Fred and Hendrik A. van Djik. Cullen’s sign. License: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 2B. Herbert L. Fred and Hendrik A. van Djik. Hemorrhagic pancreatitis. License: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 3. Cancer Research UK. ERCP. License: [CC-BY-SA]