- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Bipolar disorder is a mood disorder characterised by episodes of depression and mania or hypomania.1

It has an associated prevalence of around 1%, which is much lower than the lifetime risk associated with unipolar depression.2

The incidence of bipolar disorder follows a bimodal distribution, with two peaks in the age of onset at around 15-24 years and 45-54 years. There is a roughly equal distribution of prevalence between men and women.3,4

Bipolar disorder is commonly seen in conjunction with other mental health illnesses (e.g. anxiety disorders). In addition, bipolar disorder increases a person’s risk of physical health issues including cardiovascular disease.1

We’ve also produced a video demonstration of how a patient with bipolar disorder may present.

Aetiology

The aetiology of bipolar disorder is complex and involves genetic, environmental, and neurobiological components.

Though bipolar disorder is heritable within families, having an affected first-degree relative does not guarantee a person will be affected with the disorder, and therefore genetics alone does not explain the entire aetiology.1

Genetic factors

First-degree relatives of a person affected with bipolar disorder are at increased risk of developing bipolar and unipolar mood disorders and schizoaffective disorder. Heritability is around 60% in monozygotic twins and around 20% in dizygotic twins.1

The genetic risk associated with bipolar disorder is a type of polygenic inheritance (the sum effect of many low-penetrance mutations). Some polymorphisms in genes that code for monoamine transporters and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) are associated with an increased risk of bipolar disorder.

Evidence suggests there is an overlap in the genetic risk between bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.3 Genetic contributions may also be associated with copy number variants and gene-gene interactions.1

Environmental factors

The majority of environmental factors which contribute to the aetiology of bipolar disorder are not specific to this condition. Instead, they are associated with the risk of psychiatric disorders in general.1

Negative life events can precipitate depressive or manic episodes in people with bipolar disorder. The literature suggests that this may be mediated by circadian rhythm disruptions in genetically predisposed individuals.5

Neurobiological factors

There is some evidence that increased dopamine activity in the brain may be important in the aetiology of mania, particularly since many drugs that increase dopaminergic signalling in the central nervous system can be associated with symptoms characteristic of mania such as elevated mood, reduced need for sleep and reduction in social inhibitions.1

The presentation of psychosis in bipolar disorder suggests there may be region-specific increases in dopaminergic neurotransmission, though not necessarily a global increase in dopamine signalling.

Neuroimaging studies have so far failed to demonstrate a consistent pattern of abnormalities, though receptor occupancy studies show an exaggerated response to dopamine receptor activation through dysfunctional secondary messenger systems.6

Similar to unipolar depression, there are disturbances of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis resulting in increased cortisol secretion. Administration of exogenous corticosteroids can also result in symptoms of mania.1

Risk factors

There is no single cause for the onset of bipolar disorder, however, several risk factors have been identified as being associated with an increased likelihood of developing the condition.

These risk factors include:3,7

- Genetic factors: combined effect of many single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)

- Prenatal exposure to Toxoplasma gondii (the parasite that causes toxoplasmosis)

- Premature birth <32 weeks gestation

- Childhood maltreatment

- Postpartum period

- Cannabis use

Clinical features

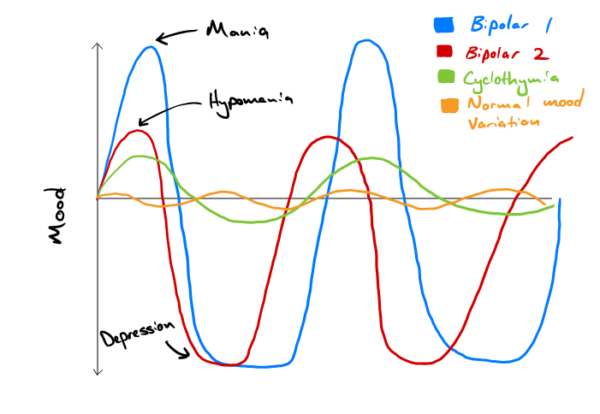

There are several types of bipolar disorder and the clinical features differ between each. The two main forms of the disorder are bipolar I and bipolar II:1

- In bipolar I, the person has experienced at least one episode of mania

- In bipolar II, the person has experienced at least one episode of hypomania, but never an episode of mania. They must have also experienced at least one episode of major depression.

Figure 1 demonstrates the difference between bipolar I and II. Also shown is cyclothymia, a related disorder characterised by a persistent instability of mood involving numerous periods of depression and mild elation, none of which are sufficiently severe or prolonged to justify a diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder or recurrent depressive disorder.8

Mania

The characteristic clinical features of mania are elevated mood, increased activity level and grandiose ideas of self-importance. In the ICD-10, mania is characterised by:8

- Elevated mood out of keeping with the patient’s circumstances

- Elation accompanied by increased energy resulting in overactivity, pressure of speech, and a decreased need for sleep

- Inability to maintain attention, often with marked distractibility

- Self-esteem which is often inflated with grandiosity and increased confidence

- Loss of normal social inhibitions

For a diagnosis, the manic episode should last for at least seven days and have a significant negative functional effect on work and social activities. Mood changes should be accompanied by an increase in energy and several of the other symptoms mentioned above.

As well as these features, mania can also occur alongside psychotic symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations, which are often auditory.8

Psychotic symptoms are mood-congruent in bipolar disorder, so therefore grandiose in nature. Flight of ideas and thought disorder may also be present.

Hypomania

Hypomania is less severe than mania and is characterised by an elevation of mood to a lesser extent than that seen in mania. In ICD-10, an episode of hypomania is characterised by:8

- Persistent, mild elevation of mood

- Increased energy and activity, usually with marked feelings of wellbeing

- Increased sociability, talkativeness, over-familiarly, increased sexual energy and a decreased need for sleep (but not to the extent that there is a significant negative effect on functioning regarding work or social activities)

- Irritability may be present

- Absence of psychotic features (delusions or hallucinations)

For a diagnosis, more than one of these features should be present for at least several days.

Although hypomania does involve some extent of functional impairment, this is lesser than that seen in mania and is not severe enough to cause the more marked impairment in occupational or social activities.8

Differential diagnoses

Several differential diagnoses should be considered in the context of suspected bipolar disorder.

Schizophrenia

Delusions and hallucinations can occur in both bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.

In bipolar disorder, these are mood congruent and so tend to be grandiose, whilst in schizophrenia, they tend to be more bizarre and difficult to understand. Where features of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are present in a roughly equal proportion, the diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder should be considered.1

Organic brain disorder

Frontal lobe pathologies can result in a loss of social inhibitions, which can also occur in mania or hypomania. Neurological investigation and imaging through CT or MRI can differentiate an organic cause from bipolar disorder.1, 9

Drug use

The effects of some psychotropic drugs can cause a similar clinical presentation to mania, but this generally resolves as the drug wears off.1 Some prescribed medications (e.g. steroids) can cause elation.

Recurrent depression

This should be distinguished from bipolar II by exploring any possible episodes of hypomania with thorough history taking.1

Emotionally unstable personality disorder (EUPD)/borderline personality disorder

This condition is characterised by affective instability which can present similarly to rapid cycling bipolar disorder. However, mood changes tend to occur more quickly in EUPD. Other features of mania such as grandiose ideas and a marked increase in energy are generally not seen in EUPD.1,9

Cyclothymia

This is a condition related to bipolar disorder which also presents with chronic mood disturbance, with both depressive and hypomanic periods. However, this is differentiated from bipolar II since, in cyclothymia, periods of depressed mood are less severe and do not meet the criteria for a depressive episode.9

Investigations

Investigations can be used to exclude organic causes of a patient’s clinical presentation and are largely context-dependent. Relevant investigations may include:1,9

- Baseline blood tests: FBC, U&Es, LFTs, TFTs, CRP, B12, folate, vitamin D, ferritin

- HIV testing

- Toxicology screen

- Physical examination including neurological examination

- CT head

Diagnosis

Bipolar disorder should be considered when there is evidence of:

- Mania: symptoms should have lasted for at least seven days

- Hypomania: symptoms should have lasted for at least four days

- Depression (characterised by low mood, loss of interest or pleasure, and low energy) with a history of manic or hypomanic episodes

A mixture of both manic and depressive features is sometimes called a mixed affective state.10

To confirm a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, a referral should be made to a specialist mental health service. This varies regionally but may take the form of a bipolar disorder service, a psychosis service, or a specialist integrated community-based service.

When a child or young person under the age of 18 is suspected of having bipolar disorder, they should be referred to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS).10

Management

Bipolar disorder is managed through the acute treatment of manic and depressive episodes and longer-term mood stabilisation.

Acute management of mania

In an acute episode of mania, people with a new diagnosis of bipolar disorder should be managed in secondary care with a trial of oral antipsychotics:11

- Haloperidol

- Olanzapine

- Quetiapine

- Risperidone

The choice of drug depends on the clinical context and individual patient factors.

If the selected drug is poorly tolerated or shows low clinical efficacy after increasing the dose as appropriate, a second antipsychotic from the list above would usually be offered.

If the patient is on antidepressant medication, this should be tapered off and discontinued.11 Benzodiazepines may be used as an adjunct to manage symptoms of increased activity and allow for better sleep.1

Acute management of depression in bipolar disorder

Managing depression in the context of bipolar disorder is difficult since standard antidepressant management options can be associated with lower efficacy in bipolar depression compared to unipolar depression. They can also be associated with a risk of inducing mania or rapid cycling.1

The recommended pharmacological options for managing depressive episodes in the context of bipolar disorder are:11

- Fluoxetine + olanzapine

- Quetiapine alone

- Olanzapine alone

- Lamotrigine alone

As well as these pharmacological options, psychological interventions such as cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) may also be useful.11

Long-term management of bipolar disorder

After the acute episode has resolved, long-term pharmacological management usually involves a mood stabilising medication such as lithium.

If lithium is not effective, sodium valproate may be added.11 Sodium valproate should not be used in pregnant women due to its teratogenic effects and is not recommended in women of childbearing age unless the illness is very severe and there is no effective alternative. In this circumstance, the patient should have a pregnancy prevention plan.12

Lithium is associated with a significant reduction in the risk of relapse with a manic episode, though evidence for its effectiveness in preventing depressive relapse is less clear.

The use of lithium is also associated with a significant reduction in death by suicide.13 Around half of patients will show a good response to lithium, although those with rapid-cycling bipolar disorder, mixed affective states or mood-incongruent features of psychosis may be less likely to respond well.1

In addition to pharmacological management, structured psychotherapies have an important role in long-term management. This can be in the form of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy or family-focused therapies.1

Complications

Complications of bipolar disorder include:1, 14

- Increased risk of death by suicide

- Increased risk of death by general medical conditions such as cardiovascular disease

- Side effects of antipsychotic drugs: these can include metabolic effects, weight gain and extrapyramidal symptoms

- Socioeconomic effects: major mental illness is associated with a negative drift down the socioeconomic ladder

Key points

- Bipolar disorder is a long-term mental illness characterised by episodes of depression and mania or hypomania with a prevalence of around 1% in the population

- The aetiology of bipolar disorder is complex and involves a genetic risk conferred by many gene polymorphisms, each with a small effect, and the interaction of this genetic risk with environmental and neurobiological factors

- Bipolar I is the more severe form of the disorder and is characterised by at least one episode of mania

- Bipolar II is characterised by at least one depressive episode with at least one hypomanic episode, but no episodes of mania

- Diagnosis is made by specialist services within secondary care using clinical criteria and the exclusion of relevant differential diagnoses

- In the acute setting, mania is managed with antipsychotic medications and discontinuation of antidepressants

- Depressive episodes are managed using antidepressants and antipsychotic medications

- In the long term, bipolar disorder is managed with mood stabilisers such as lithium and structured psychotherapies

Reviewer

Dr Julie Langan Martin

Senior Lecturer in Psychiatry and Honorary Consultant Psychiatrist

University of Glasgow

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Harrison P. Shorter Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. 2017.

- Fajutrao L, Locklear J, Priaulx J, Heyes A. A systematic review of the evidence of the burden of bipolar disorder in Europe. 2009. Available from: [LINK]

- Rowland TA, Marwaha S. Epidemiology and risk factors for bipolar disorder. 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- Tsuchiya KJ, Byrne M, Mortensen PB. Risk factors in relation to an emergence of bipolar disorder: a systematic review. 2003. Available from: [LINK]

- Alloy LB, Nusslock R, Boland EM. The development and course of bipolar spectrum disorders: an integrated reward and circadian rhythm dysregulation model. 2015. Available from: [LINK]

- Cousins DA, Butts K, Young AH. The role of dopamine in bipolar disorder. 2009. Available from: [LINK]

- Jones I, Chandra PS, Dazzan P, Howard LM. Bipolar disorder, affective psychosis, and schizophrenia in pregnancy and the post-partum period. 2014. Available from: [LINK]

- World Health Organization. ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders : Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. 1992. Available from: [LINK]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Bipolar disorder: What else might it be? 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Bipolar disorder: When should I suspect bipolar disorder? 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- National Institue for Health and Care Excellence. Bipolar disorder: Scenario: Primary care management. 2021. Available from: [LINK]