- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Being able to share information in a clear and concise way is an essential skill in all fields of medicine. This can range from simple explanations, such as why a blood test may be needed, to more complex situations, such as explaining a new diagnosis. Often, sharing information with a patient occurs naturally during a consultation. However, providing clinical information may also be the primary focus of an appointment, and in these situations, it is crucial to have a structured format to communicate effectively.

In the United Kingdom, the prevalence of epilepsy is approximately 5–10 cases per 1000. This means that explaining a diagnosis of epilepsy is a key clinical skill.

This guide provides a step-by-step approach to explaining a diagnosis of epilepsy and should be used in conjunction with our information giving guide.

Structure

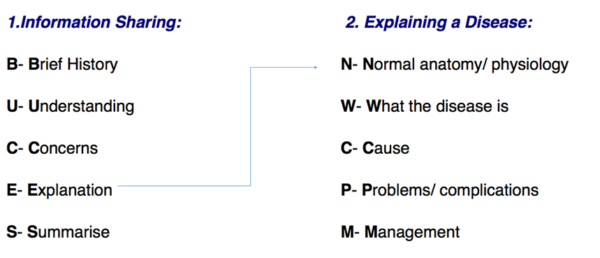

Explaining a diagnosis requires structure and adequate background knowledge of the disease. Whether the information being shared is about a procedure, a new drug or a disease, the BUCES structure (shown below) can be used.

Opening the consultation

Wash your hands and don PPE if appropriate.

Introduce yourself to the patient including your name and role.

Confirm the patient’s name and date of birth.

BUCES can be used to structure a consultation in which providing information is the primary focus.

Before explaining the various aspects of a disease, it is fundamental to have a common starting point with your patient. This helps to establish rapport and creates an open environment in which the patient can raise concerns, ask questions and gain a better understanding of their problem.

After introducing yourself, it is important to take a brief history (this is the first part of the BUCES structure):

- What has brought the patient in to see you today?

- What are their symptoms?

- Are there any risk factors that can be identified? (e.g. lifestyle/family history)

Tip: Practice taking concise histories to get the timing right. In OSCE stations, timing is crucial and you do not want to spend all your time taking a history when you are meant to be explaining a diagnosis! A rough guide would be to keep the introduction and brief history between 1-2 minutes maximum.

What does the patient understand?

Following a brief history, it is important to gauge the patient’s knowledge of their condition. Some patients may have a family member with epilepsy and therefore have a fairly good understanding of what the condition entails. Other patients may have heard of epilepsy, but only have a vague understanding of the important details. The patient sitting before you may not even know that they have epilepsy and you may be the first person to inform them of the diagnosis.

Due to these reasons, it is important to start with open questioning. Good examples include:

- “What do you think is causing your symptoms?”

- “What do you know about epilepsy?”

- “What has been explained to you about epilepsy so far?”

Open questioning should help you to determine what the patient currently understands, allowing you to tailor your explanation at an appropriate level.

At this stage, primarily focus on listening to the patient. It may also be helpful to give positive feedback as the patient talks (i.e. should a patient demonstrate some understanding, reinforce this knowledge with encouraging words and non-verbal communication such as nodding).

Checking the patient’s understanding should not be solely confined to this point of the consultation but should be done throughout by repeatedly ‘chunking and checking’.

Tip: Try using phrases such as: “Just to check that I am explaining epilepsy clearly, can you repeat back to me what you understand so far?”. This is far better than only saying “What do you understand so far?” as the onus is placed upon the quality of your explanation rather than there being an issue with the patient’s ability to understand.

What are the patient’s concerns?

The patient’s concerns should never be overlooked. A diagnosis of epilepsy can be a significant life event and provoke a variety of worries.

Asking the patient if they have any concerns before beginning your explanation allows you to specifically tailor what is most relevant to the patient, placing them at the centre of the explanation. The “ICE” (ideas, concerns and expectations) format can provide a useful structure for exploring this area further.

ICE

Ideas:

- What does the patient think is causing their symptoms?

- What is their understanding of the diagnosis?

Concerns:

- What are the patient’s concerns regarding their symptoms and diagnosis?

Expectations:

- What is the patient hoping to get out of the consultation?

Explanation

After determining the patient’s current level of understanding and concerns, you should be able to explain their condition clearly. Epilepsy can be confusing to medical students and doctors, let alone patients. Avoid medical jargon so as not to confuse your patient.

You should begin by signposting what you are going to explain to give the patient an idea of what to expect.

“I’m going to begin by talking about how our brains normally work, then I will move on to explain what epilepsy is, what may cause it, and how we can best manage it in a way that fits your individual needs.”

Epilepsy can occur at any age, from birth to late adulthood. You will need to tailor your explanation to the age of your patient, and because this is often a disorder of childhood, you should be comfortable explaining this diagnosis to parents as well.

Tip: Use the mnemonic “Normally We Can Probably Manage” to help you remember the structure of explaining a disease.

Normal anatomy/physiology

“Our brain controls how we move, what we say and do, our memories and emotions, and how we see, hear and feel things. It does all of this through many areas that talk to each other using special signals to coordinate all of the things that we do during the day. Different areas of the brain have different roles, and they usually take turns working depending on what we are doing at that moment.”

Make sure to explain the basic sensory and motor functions of the brain, as both can be involved in either a patient’s aura or how their seizure presents:

“It’s important to know that these signals can go two ways; when we are recognizing how things around us feel, look, sound, smell or taste, signals go from the outside world to our brain, and end up in the area of our brain that recognizes that particular signal (for example, our brain has a special area for vision). The other direction is used when we want to do something like move, and the area for that will send signals out to our body (for example, if we want to wave to someone, we have a special brain area that sends signals to all the muscles in our arms to make the movement). Basically, when a certain area of the brain is needed, it activates and sends signals out to our body to do its job. When an area of the brain is not required for a task, it becomes less active.” 2

What is epilepsy?

“Epilepsy is a condition that affects the brain and causes a person to have an increased tendency to have something called epileptic seizures. There are different types of epilepsy and the symptoms of each differ significantly.” 3

What is a seizure?

“A seizure is an event that occurs when there is a chaotic burst of signalling that interferes with the brain’s normal function, resulting in epilepsy symptoms. Most seizures only last a few seconds to one minute. Some people have warning signs before they experience a seizure. This pre-warning is called an aura and can be anything from a sound you hear, a warm feeling in your stomach, a smell or any other type of sensation.” 3

You can tailor your explanation to the type of seizure the patient experiences (e.g. generalized vs partial, simple vs complex, absence, myotonic, tonic-clonic):

“When someone has a seizure, they may lose consciousness, or they may stay awake during it. The symptoms of a seizure depend on the area of the brain affected by the chaotic signals. For example, if a seizure occurs in the part of the brain that only controls your left leg, you may remain awake but notice that your left leg begins shaking and moving uncontrollably. If the seizure then spreads to affect your whole brain, you would lose consciousness and your whole body would begin shaking. After a seizure, you might be very tired, confused and need sleep to recover. Full recovery typically happens within several hours.” 1

What is the cause of epilepsy?

“Epilepsy does not have one specific cause. Some people are born with epilepsy, and some develop it later on in life. It may be caused by events that happen before you are even born or during the process of birth. Epilepsy can develop later in life as a result of head injury, infection, brain tumour or a stroke. In many cases, however, the cause of epilepsy remains unknown.” 4

“There are certain circumstances and substances that increase the risk of people with epilepsy having a seizure and we call these triggers. Some examples of triggers include heavy alcohol use, dehydration, lack of sleep, use of certain medications, recreational drugs, fevers, flashing lights and missing doses of epilepsy medication.” 4

Complications of epilepsy

Outlining potential complications of epilepsy is necessary so that the patient can recognise problems early and take appropriate action. This information needs to be delivered in a sensitive manner. Being aware of common problems will encourage patients to adhere to their treatment and remain vigilant for red flags that indicate the need for urgent medical attention.

It is important not to scare the patient, but to explain that you are outlining the potential risks so that they are aware of them. Risks and the necessary modifications will vary based on the patient and their clinical profile. When discussing potential complications explain that you and the patient will need to work together as a team to reduce the likelihood that they’ll occur.

Impact on life

“Because a seizure can happen at any time, you should consider avoiding activities that put you at an increased risk of injury if a seizure were to occur, such as taking baths or swimming alone, or activities like mountain climbing or skiing. If your seizures are not controlled, you will also have to avoid driving by law until one year passes without a seizure. You may fall and injure your head during a seizure; young children or individuals with frequent seizures may be encouraged to wear a helmet to protect against this.” 5

Status epilepticus

“If prolonged seizure activity occurs without recovery, this is known as ‘status epilepticus’. Status epilepticus is a medical emergency that can result in permanent brain damage if not recognised and treated promptly. You should inform family and friends if you are carrying an emergency medicine that they can give you, usually in your mouth, if status epilepticus occurs, and they should be aware of the need to seek immediate medical attention.” 6

Sudden unexplained death in epilepsy (SUDEP)

“In rare instances, people with epilepsy may die suddenly for reasons that are unexplained, often during sleep or when no one else is around. This may occur during or after a seizure. This only happens to about 1 in every 1000 people with epilepsy per year, however, it is important to be aware of this as you can decrease your risk by taking your medications as prescribed and checking in with your doctor if your seizures are not under control.” 6

Side effects/complications of medications

You should inform the patient of the relevant side effects of the specific antiepileptic drug that has been chosen for them.

“You may experience some side effects of the medication you are taking to control your seizures. These will vary based on the medication that has been chosen for you, but may include fatigue, depression, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and sleep disturbance.” 7

If the patient is a woman of childbearing age, it is essential to make them aware of the impact specific medications can have on fetal development and the importance of effective contraception.

“These medications may also affect the development of your baby if you were to become pregnant and it is, therefore, very important to use an effective form of contraception whilst taking this treatment. Should you decide you want to start a family at a later date, you should speak with your doctor about this, so your medications can be reviewed and potentially changed to reduce the risk of developmental abnormalities whilst ensuring your seizures remain well controlled.” 6

“You may need to trial more than one medication to find one that provides the best control of your seizures with the fewest side effects.”

Management

The goal of epilepsy management is to reduce the frequency of seizures as much as possible with minimal side effects.

Explain to the patient that there are steps they can take in their own life, and there are also things you will do as their doctor. You should also explain that they will need to see you (or if necessary, a neurologist) regularly to ensure compliance and success with their current treatment regimen.

“The primary goal of treating your epilepsy is to reduce the number of seizures you experience. It may take some time to find out what works for you, and we will work together to optimize your treatment to allow you to live your life as normally as possible.”

Pharmacological

All patients diagnosed with epilepsy will be prescribed an anti-epileptic drug to take regularly to control their seizures. The choice of medication will be made based on age, sex, seizure type or epilepsy syndrome, and other medical comorbidities. Sometimes more than one is needed to achieve optimal seizure control.8

“It is extremely important to take your epilepsy medication as prescribed. You may also be given an emergency medication in the form of a small packet of gel, that someone can squish out into your cheek if you are having a very long seizure.” 8,9

Non-pharmacological

“In addition to the medication, you can choose to make some lifestyle changes that could reduce your risk of having seizures. These include making sure you get enough sleep, avoiding alcohol and recreational drugs, and managing your stress. You may notice something in your life that may trigger you to have seizures, and if you do, it is important to avoid this wherever possible. In addition, you might notice you get a warning sign, known as an aura, before you have a seizure. This can be helpful as you can sit or lie down if possible and alert someone nearby.” 5

Friends & family education

“You may find it helpful to educate some of the people that you spend a lot of time with on what to do if you have a seizure. This includes supporting your head and turning you onto your side if you fall to the ground, timing the seizure, and calling emergency services if the seizure lasts more than 5 minutes or if you injure yourself during a seizure. If you carry emergency medication, you can instruct them on where you keep it and how to give it to you. You can also tell them what they can expect after you have a seizure, such as being groggy or confused.” 10

Refractory epilepsy

Alternative approaches for refractory epilepsy may include:11

- Epilepsy surgery to remove the seizure foci

- Ketogenic diet

- Vagus nerve stimulation

- Deep brain stimulation

Closing the consultation

Summarise the key points back to the patient.

Offer the patient some leaflets on epilepsy and its management, and direct them to some reliable websites which they can use to gather more information (examples include Epilepsy Society and NHS.uk).

“We have discussed quite a lot today, including what epilepsy is, its complications and how we can work together to manage it. I realise this is a lot of information to take in, but I do have some leaflets which summarise the key points we’ve discussed. I encourage you to seek support from family or friends who can know what to do if you have a seizure, and when you require emergency medical attention. It’s important that you attend your follow-up appointments, so we can check in on how you’re managing and make adjustments where necessary.”

Ask the patient if they have any questions or concerns that have not been addressed.

“Is there anything I have explained that you’d like me to go over again?”

“Do you have any other questions before we finish?”

Arrange appropriate follow-up appointment to discuss their epilepsy further.

Thank the patient for their time.

Dispose of PPE appropriately and wash your hands.

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- NHS. Epilepsy – Symptoms. 18 September 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- Mayfield Brain & Spine. Anatomy of the Brain. April 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- NHS. Epilepsy – Overview. 18 September 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- NHS. Causes of epilepsy. 13 July 2011. Available from: [LINK]

- NHS. Living with epilepsy. 18 September 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- Epilepsy Society. Risks with epilepsy. May 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Epilepsy Foundation. Common and rare AED side effects. December 2003. Available from: [LINK]

- UpToDate. Overview of the management of epilepsy in adults. 16 September 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, NHS. Buccal (oromucosal) midazolam. December 2017. Available from: [LINK]

- Epilepsy Action. What to do if someone has a seizure. July 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- NHS. Epilepsy – Treatment. 18 September 2020. Available from: [LINK]