- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

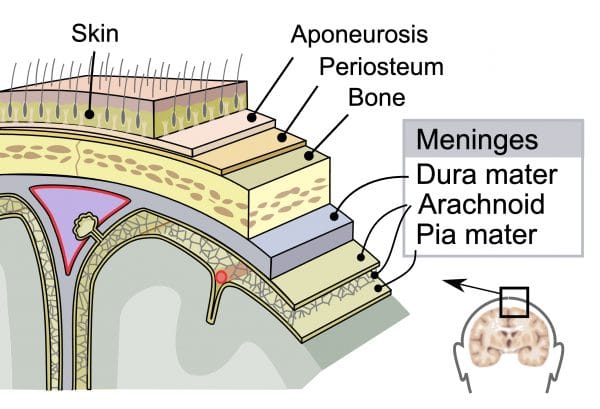

Meningitis is caused by inflammation of the meninges- the outer membranes that cover the brain and spinal cord.1 Viral meningitis is more common than bacterial meningitis, but all cases should be treated as bacterial until proven otherwise, as bacterial meningitis has a high mortality.2

Aetiology, epidemiology and risk factors

Meningitis can be caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi, or be non-infective (secondary to some cancers including leukaemia and lymphoma, autoimmune diseases or drugs).1,2

Young age is the most significant risk factor. Other risk factors include winter season, asplenia, immunocompromise, organ dysfunction, smoking and overcrowding.1

Bacterial meningitis

- The annual incidence of acute bacterial meningitis in developed countries is estimated to be 2–5 per 100,000 population1

- It is most common in infants, with a second incidence peak in teenagers and young adults2

- Bacterial meningitis is transmitted via droplet spread and usually requires frequent or prolonged close contact:1

- Bacteria which reside in the upper respiratory tract can then travel via the bloodstream to the meninges to cause invasive disease in susceptible people4

- Occasionally meningitis can occur as a result of direct spread from a local source of infection, for example, otitis media or mastoiditis

- In neonates (babies under one month) the most common organisms are Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococci), Escherichia coli, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Listeria monocytogenes1

- Risk factors in this age group include low birth weight, prematurity, premature rupture of membranes, maternal peripartum infection (risk reduced by maternal intrapartum antibiotics) and foetal hypoxia2

- In babies over three months, children and adults the most common organisms are Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) 1

- “Meningococcal disease” is a term referring to meningococcal meningitis (bacterial meningitis caused by Neisseria meningitides- 15% of cases), meningococcal sepsis/septicaemia (where Neisseria meningitides enters the bloodstream and can cause the classical petechial or purpuric rash- 25% of cases) or a combination of both (60% of cases)4

- There were 525 cases of invasive meningococcal disease in England in 2018-19, a 30% decrease from the 755 in 2017-185

- “Pneumococcal disease” refers to disease caused by invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumonia, meningitis, septicaemia/sepsis)1

- “Meningococcal disease” is a term referring to meningococcal meningitis (bacterial meningitis caused by Neisseria meningitides- 15% of cases), meningococcal sepsis/septicaemia (where Neisseria meningitides enters the bloodstream and can cause the classical petechial or purpuric rash- 25% of cases) or a combination of both (60% of cases)4

- Vaccines are available for meningococcal subgroups A, B, C, W and Y, Hib and 13 serotypes of pneumococcus6

Aseptic meningitis

Aseptic meningitis is diagnosed when cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) has white blood cells on microscopy but the gram-stain is negative and no bacteria are cultured on standard media.2

- Viral meningitis accounts for over half of all cases of meningitis. The most common pathogens are enteroviruses (echovirus, coxsackievirus). Other causes are mumps, HSV, herpes zoster, HIV, measles and influenza2

- Fungal meningitis, including Cryptococcus. Rare but can be life-threatening, more common in immunodeficient people2

- Atypical bacterial meningitis, including TB, syphilis and Lyme disease2

Clinical features

Classically described as the triad of fever, neck stiffness and altered mental state; in reality, this picture is only seen in 44% of adults with bacterial meningitis and is even less specific in children.7

Early symptoms and signs1

- Often vague and non-specific: fever, headache, nausea and/or vomiting, lethargy, irritability, muscle or joint pains, refusing food or fluids, respiratory symptoms, appearing unwell. These can be easily confused with “flu-like illnesses”

- Less common non-specific symptoms include chills, shivering, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, sore throat and coryzal symptoms

Later, more specific symptoms and signs1

- Bulging fontanelle in infants

- Neck stiffness (in children over one)2 or back rigidity

- Kernig’s sign (pain and resistance on passive knee extension with hips fully flexed)2

- Brudzinski’s sign (knees and hips flex on bending the head forward)2

- Non-blanching rash (meningococcal disease)- petechiae or purpura

- Photophobia

- Leg pain

- Mottled skin or unusual skin colour, cold hands and feet

- Altered mental state

- Prolonged capillary refill time

- Shock (tachycardia, hypotension, respiratory distress, poor urine output)2

- Neurological symptoms

- Seizures

- Paresis, focal neurological deficits (cranial nerve involvement, abnormal pupils)

As always in paediatrics, parental concern should be taken seriously. When considering the possibility of meningitis, take into account the speed of progression and the overall severity of the illness.1 Early recognition is vital to improve the prognosis of acute bacterial meningitis, which can progress rapidly, with symptoms often becoming more specific and severe over time.1

A useful way to assess all potentially unwell young children is the NICE traffic light tool (fever in under 5s).8

Differential diagnoses2

- Influenza or other viral illnesses

- Sepsis from any source

- Encephalitis (inflammation of the brain tissue)

- Intracranial or spinal abscess

- Subarachnoid haemorrhage

- Brain or CNS malignancy

Investigations

Note – investigations must not delay treatment.2

Bedside investigations

- Vital signs- could this child have sepsis; do they have signs of septic shock (e.g. hypotension, tachycardia, end-organ dysfunction)? 1

- Blood sugar- always required if an altered mental state is present and generally performed for all unwell children

Laboratory investigations2

- Biochemistry- U&Es, CRP

- Haematology- FBC, clotting studies (especially if petechial rash or sepsis)

- Blood culture

- Other tests include glucose, blood gases and meningococcal PCR

Imaging2

- CT is sometimes performed if there are focal neurological deficits or if a specific underlying cause (i.e. mastoiditis) is suspected

- Note that CT cannot exclude raised intracranial pressure

Special tests2

Lumbar puncture (LP)

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) culture is the gold standard investigation for diagnosing bacterial meningitis, and 90% of acute bacterial meningitis cases have CSF WBC >100 cells/ microlitre:9

- If possible, LP should be performed within the hour of arriving at the hospital before antibiotic treatment is commenced. However, if performing an LP will delay antibiotic treatment longer than this hour, antibiotics should be given and the LP performed later

- Contraindications to LP include raised intracranial pressure (reduced or fluctuating consciousness, bradycardia and hypertension, focal neurological signs, abnormal posturing, abnormal pupil reflexes, papilloedema, bulging fontanelle), shock, extensive or spreading purpura, convulsions (until stabilised), coagulation abnormalities (thrombocytopaenia, patient on anticoagulants)9

- CSF is analysed for cell count (to count and identify the WBCs), gram stain (to identify bacteria), glucose, protein, lactate and culture. Other tests include bacterial and viral PCRs.

- It is important to take a blood glucose level alongside (ideally just before) the LP so the ‘paired’ CSF and blood samples can be analysed

- To learn more about CSF interpretation, see the Geeky Medics guide.

Management2

The approach to the management of meningitis can be divided into:

- Supportive treatments: fluids, nutritional support, analgesia, antipyretics, antiemetics

- Treatment of the causative organism

- Treatment of any complications: metabolic disturbances, raised ICP and seizures

Meningitis is a notifiable disease and therefore needs to be reported to Public Health England.4

As always, follow local protocols to guide management.

Treatment of the causative organism

- Initially, all cases of suspected meningitis should be treated as bacterial until proven otherwise

- Further management will then be guided by the LP findings

Bacterial meningitis

- In primary care– the priority is URGENT transfer to hospital:

- If there is suspected meningococcal sepsis (with a non-blanching rash) then IM or IV benzylpenicillin can be given ONLY if this will not delay transfer (and the patient is not allergic)

- In secondary care– initial empirical therapy:4

- Children 3 months and older- IV ceftriaxone

- Children under 3 months- IV cefotaxime + amoxicillin/ampicillin (which covers for listeria)

- Once there is a confirmed organism, treatment (specific antibiotic and duration) will be guided by local microbiology guidelines

- IV dexamethasone is indicated in certain situations (i.e. children >3 months with bacteria on gram stain, frankly purulent CSF or CSF WBC >1000 cells/ microlitre)

- Treatment of contacts (prophylaxis):

- For confirmed meningococcal disease, prophylactic antibiotics should be given to close contacts within 24 hours (usually ciprofloxacin or rifampicin)

Viral meningitis

- No specific treatment, supportive management only

- If there are concerns about encephalitis, IV aciclovir is used (the treatment for herpes simplex encephalitis)

Prognosis

Meningitis is the leading infectious cause of death in children in the UK, but prognosis depends on the causative pathogen as well as the patient’s age, prior health and the severity of the illness.2

- There is a significant risk of death in bacterial meningitis2

- Pneumococcal meningitis is associated with a poorer outcome than meningitis caused by Neisseria meningitidis or Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib)1

- Viral meningitis can be managed conservatively, and most cases are self-limiting with a good prognosis1

Complications

Acute complications of meningitis

These include sepsis, septic shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation, coma, cerebral oedema, raised intracranial pressure, subdural effusions, SIADH, seizures, peripheral gangrene and death.2

Bacterial meningitis1

30–50% of survivors of acute bacterial meningitis experience permanent neurological sequelae.

Although overall mortality from acute bacterial meningitis has fallen in recent years, there has been no change in the rate of complications.

Common complications include:

- Hearing loss (33.6%)

- Seizures (12.6%)

- Motor deficit (11.6%)

- Cognitive impairment (9.1%)

- Hydrocephalus (7.1%)

- Visual disturbance (6.3%)

Appropriate follow up should be arranged prior to discharge (review with a paediatrician at 4-6 weeks), and information and support should be offered to children and their parents and carers.

Viral meningitis

There is usually complete resolution within 10 days, although there may be longer-term sequelae, including headaches, and cognitive and psychological issues.2

Key points

- There are multiple causes of meningitis- viral is the most common and bacterial has the highest mortality

- Early symptoms are often difficult to distinguish from less serious, often viral infections

- Later symptoms often include neck stiffness, photophobia, signs of shock and neurological symptoms such as seizures

- Lumbar puncture is the definitive investigation

- All suspected cases of meningitis should be treated as bacterial and given empirical antibiotics as soon as possible

- Bacterial meningitis has a high risk of permanent neurological sequelae

References

- NICE CKS. Meningitis – bacterial meningitis and meningococcal disease. Updated July 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Patient.info. Meningitis. Updated July 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Figure 1. SVG by Mysid, original by SEER Development Team [1], Jmarchn. Diagram of meninges. Licence: [CC BY-SA] Available from: [LINK]

- NICE. Meningitis (bacterial) and meningococcal septicaemia in under 16s: recognition, diagnosis and management. Updated February 2015. Available from: [LINK]

- Public Health England. Invasive meningococcal disease in England: annual laboratory-confirmed reports for epidemiological year 2018 to 2019. Published October 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- GOV.UK. Complete routine immunisation schedule. Updated December 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Van de Beek et al. Clinical features and prognostic factors in adults with bacterial meningitis. March 2005. Available from: [LINK]

- NICE. Fever in under 5s: assessment and initial management. November 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Patient.info. Lumbar Puncture. Updated October 2015. Available from: [LINK]

Reviewer

Dr Laura Doherty

ST4 Paediatrics