- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Epiglottitis is acute inflammation of the epiglottis, which can rapidly progress to severe airway obstruction, usually associated with significant systemic illness.

It is most commonly caused by the bacteria Haemophilus influenza type b (Hib) and can occur at any age. With the introduction of the Hib vaccine in the early 1990s, the incidence of epiglottitis has dropped significantly among children.

Aetiology

Anatomy

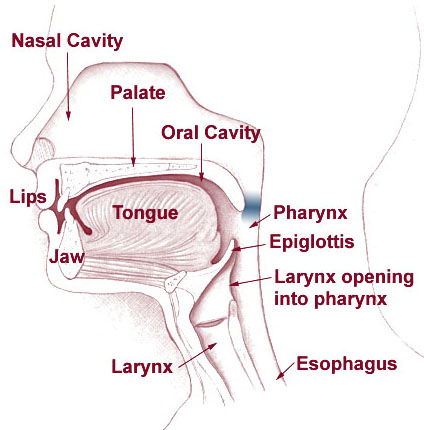

The epiglottis is a cartilaginous flap located in the larynx (Figure 1). Its function is to close over the opening to the airway (glottis) during swallowing. This prevents food or liquids from passing into the trachea and the lungs.

Given its location within the larynx, any inflammation and swelling of the epiglottis can lead to airway obstruction.

Causes of epiglottitis

The most common cause of epiglottitis is infection.

While Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) remains a common cause of epiglottitis, the Hib vaccine has significantly reduced its incidence.1,2 Other causative organisms include Streptococcus pneumoniae, group A streptococci and staphylococcus aureus.1

Other less common and rare infectious causes of epiglottitis are viral causes (for example, herpes simplex virus (HSV) and infectious mononucleosis)1 and fungal infections, such as candida.3

Non-infectious causes include thermal injuries, chemical burns from caustic agents and foreign body ingestion.1

Risk factors

Given the effectiveness of the Hib vaccine in reducing the overall incidence of epiglottitis, individuals not immunised against Haemophilus influenzae are at increased risk.

Immunocompromised individuals are at greater risk of acquiring a bacterium that can lead to epiglottitis, including those with diabetes.

In vaccinated areas, the patient most commonly affected by epiglottitis is a man in his mid-40s with additional co-morbidities.4

Clinical features

History

Typical symptoms of epiglottitis include:2,3,5

- Severe and acute onset of sore throat

- Muffled voice

- Drooling

- Inspiratory stridor

- Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) and/or painful swallowing (odynophagia)

Most patients also report a recent upper respiratory tract infection (URTI).

Compared to paediatric patients, adults often present with a slower onset of symptoms, which are less severe.3

Clinical examination

In a child with epiglottitis, no action should be taken to stimulate or irritate them, as this may trigger laryngospasm in an already critical airway. This includes examination of the oral cavity, any form of instrumentation in the airway, and even separating the child from their parent.1,2,3

Typical clinical findings in epiglottitis include:1,2,3

- Muffled voice: can be described as a ‘hot potato voice’ or may be hoarse (present in both children and adults)

- Tripod position: sitting up on hands, with the mouth open and head forward to increase airflow (commonly seen in children)

- Drooling (more common in children)

- Signs of respiratory distress: dyspnoea, tachypnoea, use of accessory muscles and cyanosis are severe findings and indicate impending respiratory failure (seen in both children and adults)

- Inspiratory stridor: can sometimes be a late finding and indicates advanced upper airway obstruction.

- Hypoxia

- Tachycardia

- Fever

Differential diagnoses

Differential diagnoses of sore throat include:1,3

- Acute tonsillitis

- Acute pharyngitis

- Peri-tonsillar abscess (quinsy): usually presents with fever, sore throat, trismus, and muffled voice (not hoarse).

- Deep neck space infection: severe sore throat that can present with neck swelling (and possibly stridor)

Differential diagnoses of stridor include:1,3

- Laryngotracheobronchitis (Croup)

- Foreign body inhalation

- Anaphylaxis

- Laryngitis

Investigations

Investigations in the immediate period are avoided as the condition is time critical, unless the patient is stable.

The main priority is to avoid further agitating the patient and precipitating airway obstruction, particularly in children.

The diagnosis of epiglottitis is mainly clinical. Therefore, it is crucial to have senior support early on, including those with advanced airway skills.

If there is a strong clinical suspicion of epiglottitis in an unstable patient, they will likely be taken to a controlled environment, such as the operating theatre, for examination of the airway plus endotracheal intubation or a surgical airway.1

Only once the airway is secure can other investigations be performed, such as blood tests, blood culture and a culture swab from the epiglottis.

First-line investigations in the stable patient

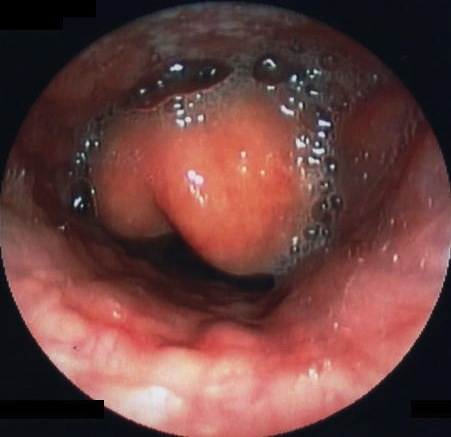

The first line investigation, in a stable patient, is direct flexible (or rigid) laryngoscopy to visualise the airway. Normally performed by ENT, this confirms swelling and inflammation of the epiglottis and inflammation of surrounding supraglottic structures.1,3

This should only be performed in a controlled setting, such as an operating theatre, with anaesthetics and ENT present. This will allow for an airway to be secured if required, either via endotracheal intubation or an emergency surgical airway (i.e. tracheostomy).1,3

Other investigations

Other investigations can be carried out once the airway is secure.

Second-line imaging1,3

A lateral neck radiograph is usually only carried out in a stable adult patient or a stable, cooperative child if there is diagnostic uncertainty. The child should not be sent unaccompanied for the examination.

It may reveal a severely swollen epiglottis, called the ‘thumbprint sign’.

Imaging may not be necessary if the diagnosis is made with clinical examination and laryngoscopy.

Laboratory investigations1,3

Blood tests are only performed in a stable patient or once the airway is secure. No blood tests should be attempted in a child until the airway is secure.

Relevant laboratory investigations include:

- Full blood count: raised white cells can indicate infection

- CRP: often raised in acute infection

- Liver function tests

- Urea & electrolytes

- Blood cultures: to help guide future antibiotic choices.

- Culture swab from epiglottis: to identify the causative organism and guide antibiotic choice. Only performed by senior members of staff.

Management

The main priority is to secure the airway in a controlled environment, as patients (particularly children) can deteriorate quickly. Involve senior members of staff and airway specialists (anaesthetics and ENT) early in the management of epiglottitis.

Once the patient is stable, they will be managed in critical care with monitoring, IV antibiotics and subsequent extubation in a controlled setting.

Take no action that may stimulate a child with epiglottitis. Similar caution should be used in adults with acute severe epiglottitis.

Approach the patient with suspected epiglottitis with an ABCDE approach, bearing in mind this is an airway emergency. No other procedures or clinical examination should delay control of the airway.

Initial management

Manage the patient in an upright position (lying a patient supine can worsen airway obstruction).3

Have the airway assessed and secured by a relevant specialist (ENT or anaesthetics). This can take two main forms:1,3

- Endotracheal intubation

- Surgical airway if intubation is not possible (e.g. tracheostomy or cricothyroidotomy).

Additional management

Additional management of epiglottitis includes:

- Nebulised adrenaline: can be used back-to-back if required.

- High-flow oxygen: humified oxygen may be required in some cases

- Intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics: a third-generation cephalosporin (e.g. ceftriaxone or cefuroxime) is often used but always follow local empirical antibiotic guidelines.2 Antibiotic therapy can be tailored once culture results are known.

- Corticosteroids (e.g., dexamethasone): usually given as a stat dose on acute presentation. Administered orally in children to avoid cannulation but could be intravenous in adults if stable. Then, it is continued regularly whilst the patient recovers (IV or oral). Whilst not proven in clinical trials, corticosteroids may help reduce supraglottic inflammation.

- Fluid replacement therapy: given orally in children to avoid cannulation

- Analgesia

Complications

Complications of epiglottitis include:1,3,6

- Epiglottic abscess: may require drainage

- Deep neck space infections: may occur if the infection extends beyond the epiglottis. This can be cellulitis or an abscess, such as retro- and parapharyngeal abscesses

- Mediastinitis: as the epiglottis involves the retropharyngeal space, the infection can spread to the mediastinum (a life-threatening condition)

Key points

- Epiglottitis is commonly caused by the bacteria Haemophilus influenzae type b. Since the introduction of the Hib vaccine, incidence among children has markedly reduced.

- The most commonly affected patient is now a man in his mid-40s.

- Epiglottitis represents a life-threatening condition which can quickly lead to severe airway obstruction with high mortality. It is crucial to escalate early to senior members of the team and relevant specialties (anaesthetics and ENT).

- The classic presenting features of epiglottitis are acute onset of sore throat, fever, muffled voice, drooling and stridor

- Avoid any action that may stimulate a child with epiglottitis, as this may worsen airway obstruction.

- The main priority in a patient with epiglottitis is securing the airway. This often involves patients being managed in a controlled setting, such as theatre.

- Investigations in the immediate period are generally avoided as the condition is time-critical unless the patient is stable.

- First-line investigation is with flexible or rigid laryngoscopy to visualise the epiglottis and airway. This should be done in a controlled setting, with a team present who can establish an airway in an emergency.

- First-line treatment is securing the airway before commencing antibiotics, usually third-generation cephalosporins, to treat the infection.

Reviewer

Miss Lucy Li

ST4 otolaryngology

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Guerra AM, Waseem M. 2022. Epiglottitis. StatPearls. Available from: [LINK]

- Lindquist B, Zachariah S, Kulkarni A. 2017. Adult Epiglottitis: A Case Series. Perm J. 21:16-089. doi: 10.7812/TPP/16-089.

- BMJ Best Practice. Epiglottitis. BMJ Publishing Group. Last updated 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- Shah R K, Stocks C. 2010. Epiglottitis in the United States: national trends, variances, prognosis, and management. Laryngoscope. 120(6):1256-62. doi: 10.1002/lary.20921.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Sore Throat – Acute. CKS Health Topic. Available from: [LINK]

- Ito K, Chitose H, Koganemaru M. 2011. Four cases of acute epiglottitis with a peritonsillar abscess. Auris Nasus Larynx. 38(2):284-8

Image references

- Figure 1. Prof. Squirrel / Arcadian. Head neck vsphincter. License: [Public domain]

- Figure 2. 藤澤孝志.Epiglottitis endoscopy. License: [CC BY-SA]