- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Whooping cough is a highly contagious, acute respiratory tract infection which can be life-threatening, especially in babies under three months of age. It is prolonged (previously being referred to as the “100-day cough”) and severe, with spasms of coughing so intense they can lead to cyanosis or apnoea.1

Whooping cough is the most common vaccine-preventable disease in the world and causes almost 300,000 deaths in children worldwide each year.2,3

Aetiology

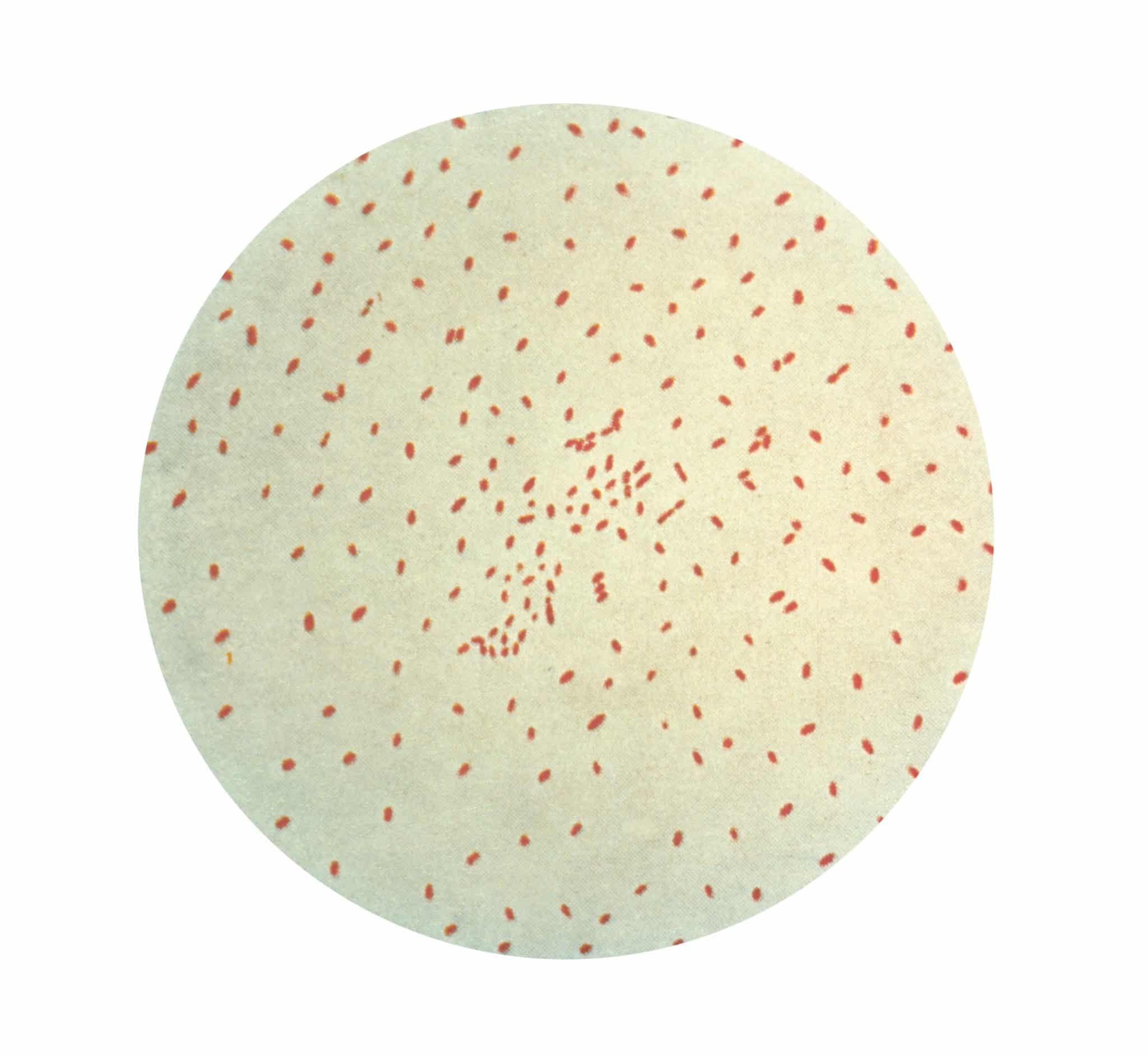

Whooping cough is usually caused by the Gram-negative coccobacillus Bordetella pertussis, but a milder infection can be caused by Bordetella parapertussis.1 The bacteria are transmitted via respiratory droplets, with an incubation period of 6-20 days.4

Due to the success of the vaccination programme, whooping cough is no longer endemic in the UK but does still occur in epidemics, with peaks of cases occurring every three to four years.5

Risk factors

Whooping cough is more common in infants under three months and in unvaccinated children (who experience a more severe illness).5

Clinical features

Whooping cough initially presents with a non-specific catarrhal phase, with nasal discharge, sore throat, conjunctivitis, malaise, dry cough and mild fever.5 This prodrome lasts one to two weeks.4

This then progresses to the paroxysmal phase, where the classic “whoop” might be heard.5 Episodes of a severe dry cough (which can be triggered by a startle) can be so prolonged (without the child being able to draw breath) that they can become cyanotic, choking and gasping.1

In younger children, an inspiratory “whoop” can then be heard as the child tries to catch their breath through partially closed vocal cords. There is also often post-tussive vomiting, and paroxysms may result in apnoea in younger infants.5

The symptoms tend to be more severe in younger children, but patients are generally relatively well between paroxysms.5 The cough can persist for several weeks even when treated with antibiotics.5

The final convalescent phase can last two months or more, as the paroxysms reduce in frequency and severity.5

Differential diagnoses

Other causes of acute cough to consider include:

- Viral upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) and post-viral cough

- Pneumonia (bacterial or viral)

Other causes of chronic cough to consider include:

Investigations

Whooping cough is a notifiable disease, and notification procedures should be carried out when it is clinically suspected.1 Once notified the local health protection team will advise on testing.5

Options for laboratory testing to confirm the diagnosis include:5

- Culture of nasopharyngeal aspirates or nasal swabs

- PCR of the throat or nasopharyngeal swabs

- Serology or oral fluid testing for anti-pertussis IgG

Management

Vaccination

Prevention of whooping cough caused by Bordetella pertussis is with the pertussis vaccine which was introduced in the 1950s.4 It is now given as part of the DTaP/IPV/Hib/HepB combined vaccine administered at 8, 12 and 16 weeks of age, and then as DTaP/IPV at 3 years 4 months, and from 16 weeks of pregnancy (to protect the very young infant).6

However, B. parapertussis is not covered by the present vaccine and both natural and vaccine immunity decrease over time.1,4

Management of acute infection

There should be a low threshold for admitting unwell children to hospital, especially those under six months of age.

Macrolide antibiotics (erythromycin, azithromycin or clarithromycin) are used if the onset of the cough was within the last 21 days.5 Antibiotic treatment does not affect the clinical course of the illness, but does eliminate B. pertussis from the nasopharynx and so is used to reduce infectivity.7

Other supportive care advice includes rest, hydration, and analgesics/antipyretics.5

Children with whooping cough should stay home from school, and healthcare workers should avoid entering the workplace, until 48 hours after antibiotics have started, or 21 days after symptom onset if antibiotic treatment is not given.5

Prophylaxis

Antibiotic prophylaxis (macrolide antibiotics) should be considered for contacts of an index case, particularly if the contact fits into one of the priority groups, such as preterm or unimmunised babies, unimmunised pregnant mothers and healthcare workers.1

Complications

The most serious complications and deaths occur in infants younger than 6 months old.4 In this age group, pertussis has a mortality rate of 3.5%.5

Bordetella pertussis infection can be complicated by pneumonia (secondary infection), and the paroxysms can lead to apnoea and/or cerebral hypoxia (with subsequent brain damage, seizures or encephalopathy).4,5

Recurrent vomiting can lead to dehydration and weight loss. The increased thoracic pressure can cause rectal prolapse, umbilical and inguinal hernias, rib fractures or pneumothorax.4,5

Less serious complications include epistaxis, subconjunctival haemorrhage, facial and truncal petechiae and otitis media.4

Key points

- Whooping cough is a highly infectious notifiable bacterial illness usually caused by the Gram-negative coccobacillus Bordetella pertussis

- Whooping cough initially presents with a non-specific catarrhal phase, followed by the paroxysmal phase with episodes of severe dry cough

- The most at-risk group are infants under six months old

- Antibiotics (macrolides) are used to reduce infectivity, but the cough can last for several months

- Vaccinations are given routinely from two months of age and during pregnancy

- Complications may include pneumonia, apnea and cerebral hypoxia (caused by severe paroxysmal cough)

Reviewer

Dr Amraj Dhami

Neonatal Registrar

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Patient UK. Whooping cough. Last edited September 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- Hartzell and Blaylock. Whooping Cough in 2014 and Beyond. Published July 2014. Available from: [LINK]

- Crowcroft and Pebody. Recent developments in pertussis. Published June 2006. Available from: [LINK]

- UK Health Security Agency. Pertussis: the green book, chapter 24. Published March 2013. Available from: [LINK]

- NICE CKS. Whooping cough. Last revised April 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- UK Health Security Agency. The complete routine immunisation schedule from February 2022. Updated February 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- Altunaiji et al. Antibiotics for whooping cough (pertussis). Published July 2007. Available from: [LINK]

Image references

- Figure 1. CDC Public Health Image Library. Gram stain of the bacteria Bordetella pertussis. License: [Public domain]