- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Occlusion is the relationship between the maxillary and mandibular teeth at rest and in function. This is a topic that often leaves dental students and even some qualified dentists scratching their heads, and for that reason, occlusion is frequently overlooked when it comes to providing patients with dental restorations. Occlusion is an integral part of dental treatment as dentists cannot repair, move or remove teeth without affecting occlusion.1

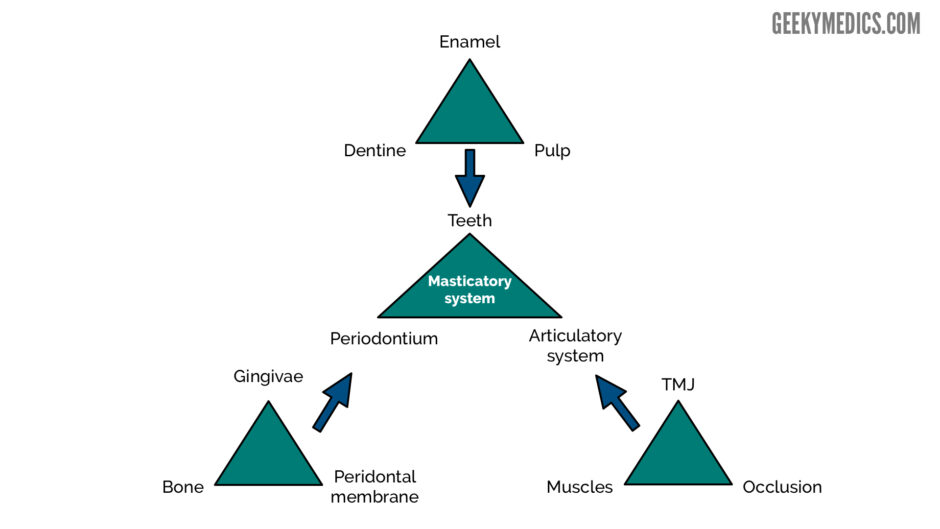

The masticatory system comprises the teeth, the periodontal tissues and the articulatory system. The articulatory system is in itself a triumvirate comprising the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), muscles of mastication and occlusion.

Terminology

Centric occlusion

Centric occlusion (CO) is the occlusion the patient makes when they fit their teeth together in maximum intercuspation. It is the contact between the greatest number of opposing teeth meaning CO is tooth determined. This is the occlusion the patient nearly always makes when they are asked to bite together as it is the bite they are habituated to.1

Synonyms:

- intercuspal position (ICP)

- bite of convenience

- habitual bite

Centric relation

Centric relation (CR) is the mandible’s relationship to the maxilla when the condyles are in their most anterior superior position in the glenoid fossae. In other words, the anterior surfaces of the condyles are braced against the most superior part of the distal facing incline of the glenoid fossa, with the articular disc between them.1

It is important to understand that centric relation is not an occlusion and has nothing to do with teeth, it is instead a jaw relationship. As it is not tooth determined, we can reproduce this position with or without teeth present making it a good position to restore a patient’s occlusion to.

Synonyms:

- centric jaw relation

- terminal hinge (axis) relation

- retruded axis position

Retruded contact position

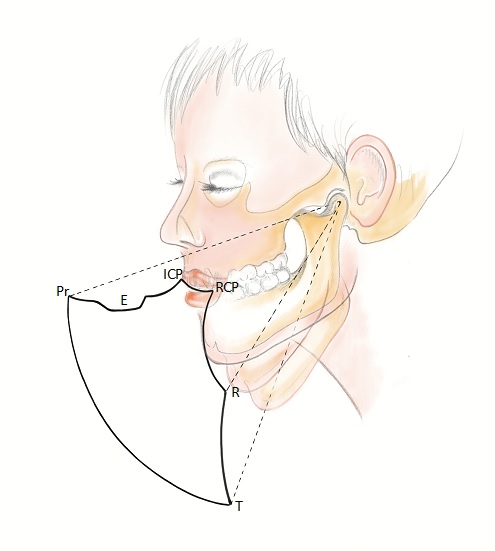

Retruded contact position (RCP) is the relationship of the mandible to the maxilla when the condyles are in their most posterior positions in the glenoid fossae and initial tooth contact has occurred.4

Centric relation contact position

Centric relation contact position (CRCP) is the relationship of the mandible to the maxilla when the condyles are in their most superior positions in the glenoid fossae and initial tooth contact has occurred.4

If you position the patient in centric relation and slowly start to close, the first contact point that meets is the centric relation contact position. This is not to be confused with the retruded contact position, which is the first tooth contact point when the condyle is positioned posteriorly within the glenoid fossa.

Slide or slip is when a patient in CRCP slides into CO. In 10% of patients, there is no difference between their CO and CR and therefore they do not have this slide.4

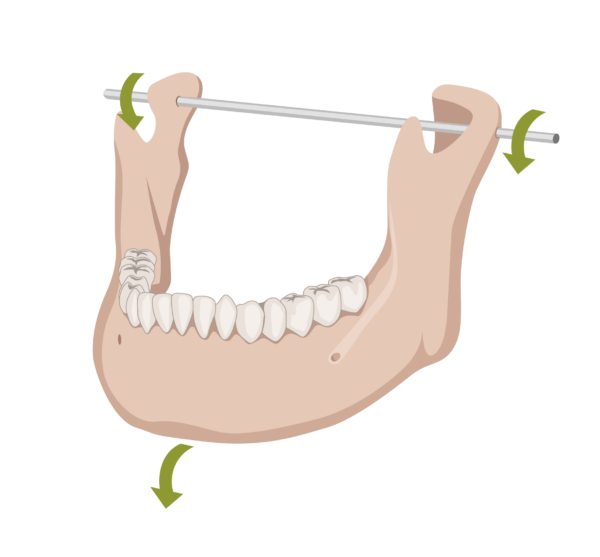

Terminal hinge axis and retruded arc of closure

Terminal hinge axis is an imaginary axis that runs through both condylar regions when the condyles are in CR, in relation to the maxilla. This may also be referred to as the retruded condylar axis.1

Retruded arc of closure is the arc of opening and closing made by the mandible whilst the condyles are rotating about the terminal hinge axis.4

Static and dynamic occlusion

Static occlusion is the contacts between the teeth when the mandible is not moving.1

Dynamic occlusion is the contacts between the teeth when the mandible is moving.1

The working side is the side of the mandible towards which the mandible is moving.1

The non-working side is the side of the mandible away from which the mandible is moving.1

Freedom in centric occlusion means that in CO, the mandible still has room to move slightly anteriorly, for a short distance, whilst maintaining posterior tooth to tooth contact.1

Occlusal approach to treatment

The conformative approach is when pretreatment occlusion is preserved.1

The reorganised approach is when pretreatment occlusion is changed, such as in orthodontic treatments and advanced restorative procedures.1

Why is occlusion important?

Without adequate knowledge of occlusion, dentists are untrained to recognise and manage symptoms of occlusal disorders. These undiagnosed problematic occlusions could lead to long term patient discomfort.6

Restorations can be made more predictable and with increased longevity, if occlusal harmony is maintained.

A balanced occlusion after restorative treatment can prevent teeth and restorations from fracture, wear, and pain.

Classification of static occlusion

Key occlusal classifications are shown below.

British standards institute classification of incisor relationship

This is the relationship between the maxillary and mandibular incisors when in centric occlusion.7

Class I

The lower incisal edges occlude with or lie immediately below the cingulum plateau of the upper incisors.

Class II

The lower incisal edges occlude posterior to the cingulum plateau of the upper incisors. Class II incisal relationship is further divided into two divisions:

- Division I: the upper central incisors are proclined, usually resulting in an increased overjet

- Division II: the upper central incisors are retroclined, usually resulting in a decreased overjet

Class III

The lower incisal edges occlude anterior to the cingulum plateau of the upper incisors.

Angles molar classification

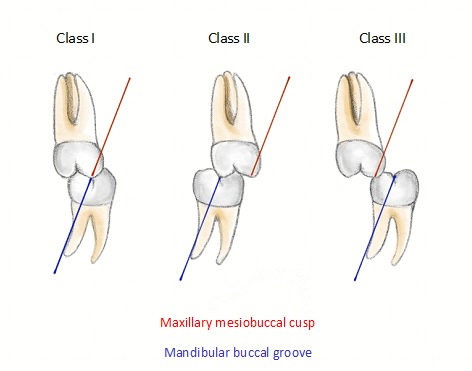

This is the relationship between the maxillary and mandibular first molars when in centric occlusion.7

Class I

The mesiobuccal cusp of the upper first permanent molar occludes with the mesiobuccal groove of the lower first permanent molar.

Class II

The mesiobuccal cusp of the upper first permanent molar occludes anterior to the mesiobuccal groove of the lower first permanent molar.

Class III

The mesiobuccal cusp of the upper first permanent molar occludes posterior to the mesiobuccal groove of the lower first permanent molar.

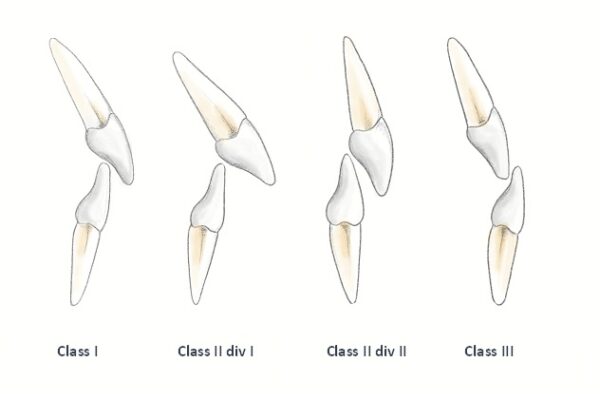

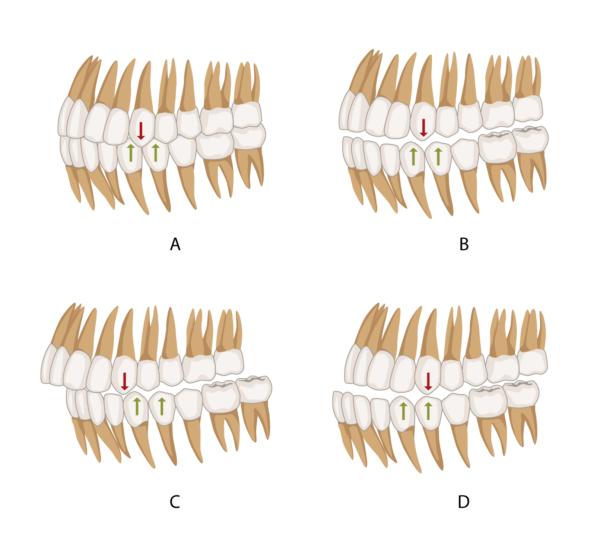

Canine classification

This is the relationship between the maxillary and mandibular canines in centric occlusion.

Class I

The mesial slope of the upper canine lies within the canine-first premolar embrasure (A, B).

Class II

The mesial slope of the upper canine lies in front of the distal slope of the lower canine (C).

Class III

The mesial slope of the upper canine lies behind the distal slope of the lower canine (D).

Dynamic occlusion

The pathways along which the mandible moves are determined by the muscles of mastication and two guidance systems.1

Posterior guidance

This is provided by the TMJ. The mandible moves along this guidance pathway as the heads of the condyles move downwards and forwards in the glenoid fossae and on to the articular tubercle.1

Anterior guidance

This is a term that refers to the guidance that is not provided by the TMJ, but instead, the guidance is provided by the posterior and anterior teeth (essentially, anything in front of the TMJ). Any teeth that are touching during protrusive or lateral movements of the mandible are providing anterior guidance.1

Note: Despite the name, anterior guidance does not specifically refer to the anterior teeth, the posterior teeth can also be involved, particularly in patients with Angle’s class III occlusions.

Anterior guidance is further classified into protrusive movements and lateral excursion.

Protrusive movement

This is the forward sliding of the mandible to come to an edge to edge incisal relationship. Ideally, the palatal surfaces of the anterior teeth provide the guidance and at the point of protrusion, all of the posterior teeth should disclude, protecting the posterior teeth from wear and fracture.1

Lateral excursion

Lateral excursions are a form of dynamic occlusion which occurs when the mandible moves left or right with teeth in contact. They can be described as:

- Canine guidance: canine protected articulation. The canines on the working side are the only occluding teeth whilst all other teeth become discluded when carrying out lateral movements.11

- Group function: multiple contacts between the maxillary and mandibular teeth, in lateral movements, on the working-side, whilst the rest of the teeth become discluded. Simultaneous contact of several teeth acts as a group to distribute occlusal forces.11

- A combination of both canine guidance and group function.

The envelope of function

The envelope of function is defined as the 3D space contained within the envelope of motion that defines mandibular movement during masticatory function.11 In simple terms, this is the relationship between the maxillary and mandibular incisors during mandibular movement.

The position of the maxillary and mandibular incisors in relation to each other can affect the freedom in centric occlusion. A tight space between these teeth leads to a reduced envelope of function and little or no freedom in centric occlusion.1 The less space there is to move, the more chance of tooth wear between these antagonistic teeth.

Some common examples of occlusions that may not have this freedom include:

- Class II division II cases

- Anterior crown restorations with palatal surfaces which are too thick

- An edge to edge occlusion

- An anterior open bite

Occlusal interferences

Occlusal interferences occur when the teeth and TMJ movements are not in harmony.11

There are four types of occlusal interference.

Centric interference

A premature contact occurring when the mandible closes with the condyle in its optimum (superior) position within the glenoid fossa. This causes the mandible to deflect from the optimum position. Centric interference can occur in the presence of tilted teeth or in orthodontically treated patients.

Working side interference

Any contact on the working side that is not producing canine guidance or group function

Non-working side interference

An over-erupted tooth, a tilted tooth or a high cusp creating a deflective contact on the non-working side as the mandible is trying to move laterally to the working side.

Protrusive interference

A deflective contact on a posterior tooth/teeth whilst trying to undergo protrusive movements.

Jaw movements

The movement of the mandible occurs in two different ways:

- Hinge movement

- Translational movement

Hinge movement

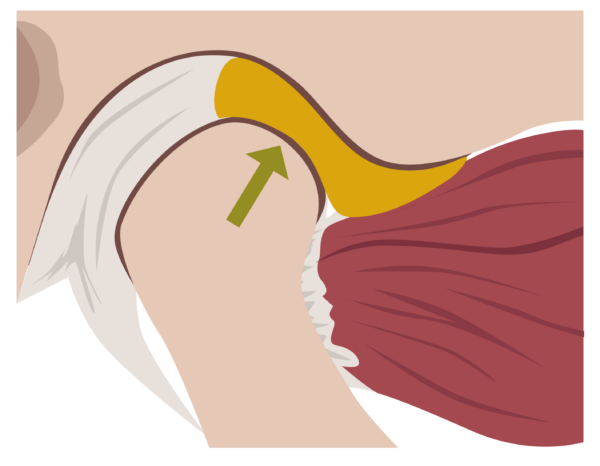

Hinge movement involves the initial opening (up to 20-25mm) when the head of the mandible rotates around the terminal hinge axis.

Translational movement

After hinge movement has occurred, wider opening results in a gliding movement as the head of mandible and disc slide forward together, out of the glenoid fossa and situate just posterior to the articular eminence. This is called translational movement.1

The ideal occlusion

It is important to note that we should never restore a patient to the ideal occlusion if their current malocclusion is well tolerated and non-damaging.1

Features of an ideal occlusion

At a tooth level:

- Multiple simultaneous contacts in CO

- Forces directed down along the long axis of posterior teeth

- Cusp to fossa contacts as opposed to cusp to incline contacts

- Smooth and shallow guidance contacts

At a system level:

- Absence of posterior and non-working side interferences

- Centric occlusion equals centric relation

- Freedom in centric occlusion

- Canine guidance rather than group function

- Protrusive movement with guidance from anterior teeth, which cause immediate disclusion of posterior teeth

At a patient level:

- An occlusion within the neuromuscular tolerances of the patient, which is determined using an occlusal hard plastic splint1

A quick guide on how to assess occlusion

One mistake made by many dentists and dental students is the failure to assess the occlusion before placing a restoration. Without pre-assessing the occlusion, there is no way to achieve a conformative restoration. Alongside this, an articulatory examination can be conducted which involves a series of questions related to the patient’s bite.

Equipment needed

Equipment required for an occlusal examination includes:

- Articulating paper in 2 different colours (preferably 20 microns as the thinner the paper is, the more accurate the bite marks)

- Miller’s forceps

- Shim stock

It is important to perform these steps at the start of the appointment. This will prevent the patients bite from being altered due to fatigue from having their mouth open for too long or loss of proprioception due to the administration of local anaesthetic.

Step by step occlusal examination

Dry the teeth

This will allow better colour transfer from the articulating paper. Additionally, applying Vaseline on articulating paper can help with colour transfer on to teeth.

Shim stock

This is a thin strip of polyester film used to identify the presence or absence of occlusal or proximal contacts.9 Use the shim stock in between and across the two arches in order to establish teeth that are naturally occluding and naturally discluding. A positive contact will result in a ‘tug back’ of the shim stock and a negative contact will result in the strip removing itself from the occlusion on pulling. Record in the patient’s notes where the shim stock holds are present.

Mark the dynamic contacts

Using Miller’s forceps to grasp the articulating paper, get the patient to slide their mandible laterally, forwards and backwards with the paper between their teeth. Start with dynamic contacts to prevent static contacts from being rubbed off.

Mark the static contacts

Using a different coloured articulating paper (preferably a lighter colour to prevent coverage of the dynamic contacts), get the patient to bite down a few times with the paper between the maxillary and mandibular teeth on the left side before progressing on to the right.

Assess and make a note of the contacts

Some clinicians like to take a mental note of the contacts to then be able to conform their restoration to that original occlusion. Alternatively, clinical photos, occlusal drawings/sketches or notes can be taken instead for a keepsake record.

Note that some contacts will be heavier than others and these will show up darker in the occlusal assessment as more colour is transferred. These contacts are where the patient will be more occlusally aware.

After placing the restoration this process should be repeated. The restoration should then be adjusted in order to match the contacts and shim stock holds that were present before the restoration was placed, in order to achieve a conformative restoration. When placing indirect restorations, such as crowns, check the occlusal contacts with the crown seated but not cemented and adjust accordingly.

Key points

- The articulatory system comprises the temporomandibular joints, muscles of mastication and the occlusion.

- Key static occlusal classifications include incisal classification, molar classification and canine classification.

- Occlusion should be assessed both before and after restorative treatment to ensure predictable and lasting restorations.

- Patients should not be restored to the ‘ideal occlusion’ if their current malocclusion is well-tolerated.

References

- Davies and Gray. What is occlusion? Published in 2001. Available from: [LINK]

- Copyright of Geeky Medics. Adapted from an original image by Davies and Gray.

- Copyright of Geeky Medics.

- Wilson and Banerjee. Recording the retruded contact position: a review of clinical techniques. Published in 2004. Available from: [LINK]

- Copyright of Geeky Medics

- Shillingburg et al. Fundamentals of fixed prosthodontics fourth edition. Published in 2012.

- Mitchell, S. J. Littlewood, Z. Nelson-Moon, and F. Dyer. An introduction to orthodontics third edition. Published in 2013.

- Incisor classification. License: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Molar classification. License: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Copyright of Geeky Medics

- The journal of prosthetic dentistry. The glossary of prosthodontic terms ninth edition. Published 2017. Available from: [LINK]

- Posselt’s envelope of motion. License: [CC BY-SA 4.0] Available from: [LINK]

- Dentinal Tubules. I think that crown/filling is a bit high… Webinar. Uploaded 2020. Available from: [LINK]

Reviewer

Dr Stephen Harrison

Restorative Dentist

Editor

Dr Louise Griffith

General Dental Practitioner and Honorary Research Associate