- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

This article is intended to provide healthcare students with a brief overview of common anaesthetic equipment you may encounter while on placement in the perioperative environment. For more information on airway management equipment, see our guide to airway equipment.

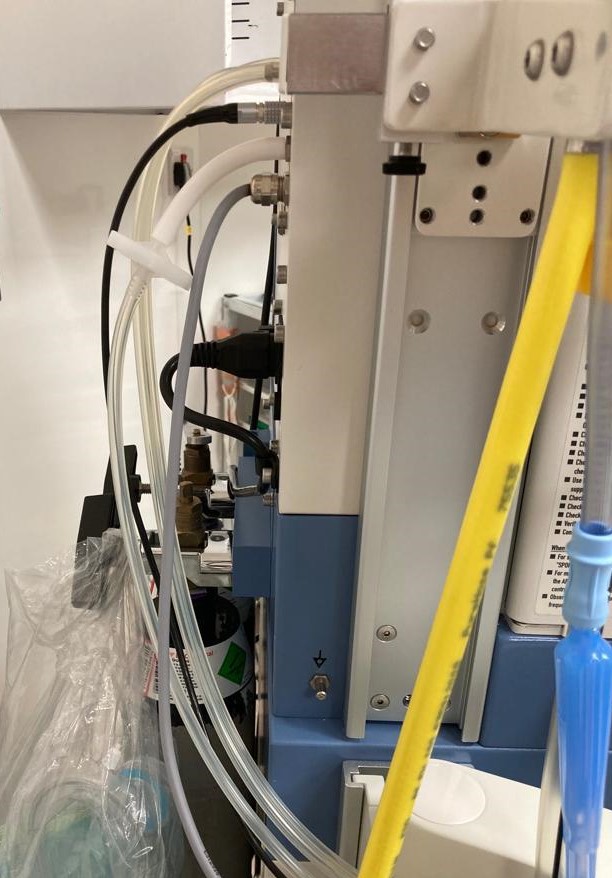

The anaesthetic machine

An anaesthetic machine generates, mixes, and delivers a flow of medical gases and inhalational anaesthetic agents to the patient to induce and maintain anaesthesia.

The machine is generally used with a mechanical ventilator, breathing system, suction equipment, and patient monitoring devices. Although strictly speaking, the term “anaesthetic machine” refers only to the component that generates the gas flow, most modern machines integrate all these devices into one combined freestanding unit, commonly called the “anaesthetic machine” for simplicity.¹

The medical gases used in anaesthesia (oxygen, medical air, and nitrous oxide) are generally supplied under high pressure via pipeline to the anaesthetic machine, with cylinders for emergency backup.²

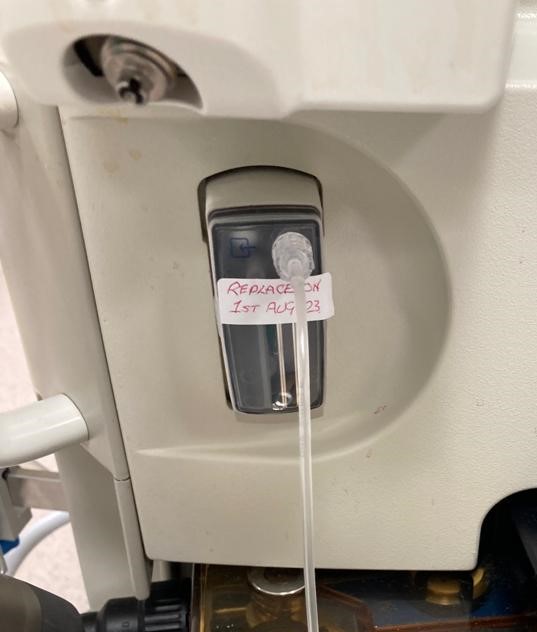

Vaporisers

‘Volatile’ anaesthetic agents (isoflurane, desflurane, and sevoflurane), used for the maintenance of general anaesthesia, are liquids at room temperature and thus require a vaporiser for inhalational administration.

An anaesthetic vaporiser is a device generally attached to an anaesthetic machine that delivers a known concentration of a volatile anaesthetic agent to the patient. A vaporiser works by controlling the vaporisation of the liquid agent and then accurately calibrating the concentration of the agent, which is added to the fresh gas flow (oxygen and medical air) for delivery to the patient.

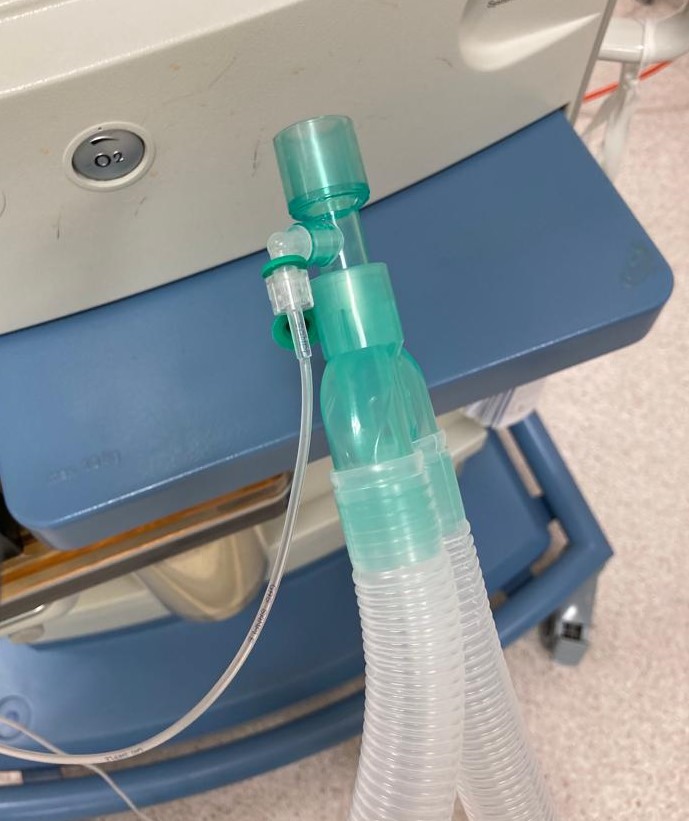

Anaesthetic breathing circuit

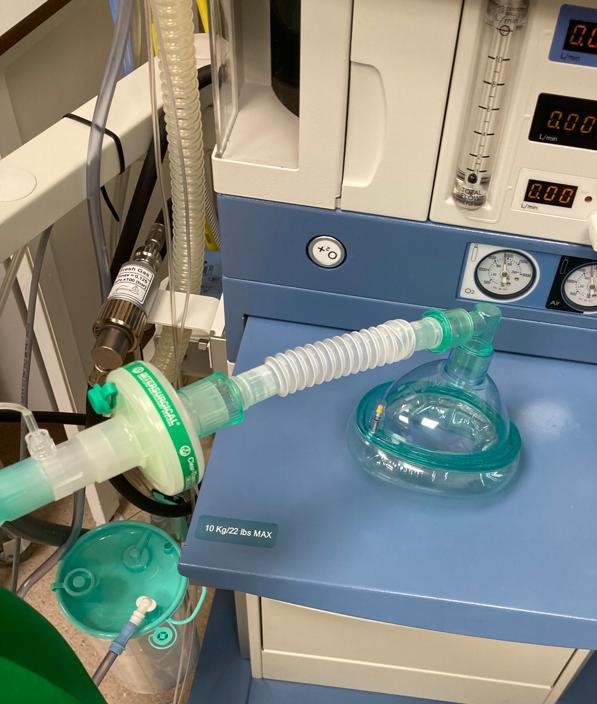

A ‘breathing system’ is an arrangement of tubes and other components that transports gases between the anaesthetic machine and the patient. The most common breathing system used in modern anaesthesia is the ‘circle system’.³

This type of circuit has several key advantages:

- Preserves anaesthetic gases, making volatile anaesthesia more cost-effective

- Preserves heat and moisture

- It is a closed-circuit system which reduces fire risk

The circuit contains a reservoir bag for monitoring the patient’s respiration and ventilating the patient if required. The bag also acts as a gas reservoir, protecting the patient from excessively high pressures within the breathing system.

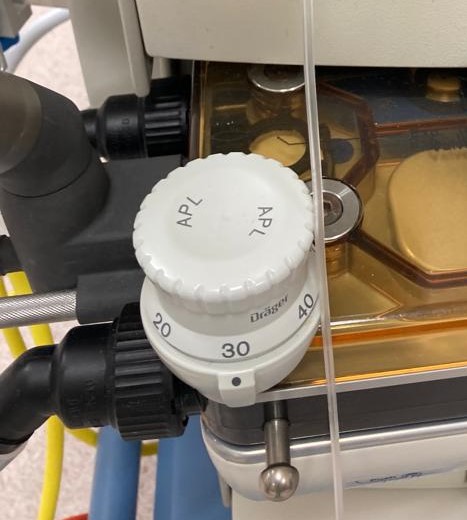

The adjustable pressure-limiting (APL) valve is also part of the anaesthetic machine breathing circuit. The APL valve is generally only used during spontaneous or manual ventilation. During spontaneous breathing, the valve is left fully open, and gas flows through the valve during exhalation. When manually assisted ventilation is used, the APL valve should be closed enough to achieve the desired inspiratory pressure.

At the ‘patient end’ of the breathing system is a heat and moisture exchange (HME) filter, which warms and humidifies inspired gases by conserving exhaled heat and moisture. A catheter mount is often used to attach the breathing circuit to a facemask, i-gel®, laryngeal mask airway (LMA) or endotracheal tube.

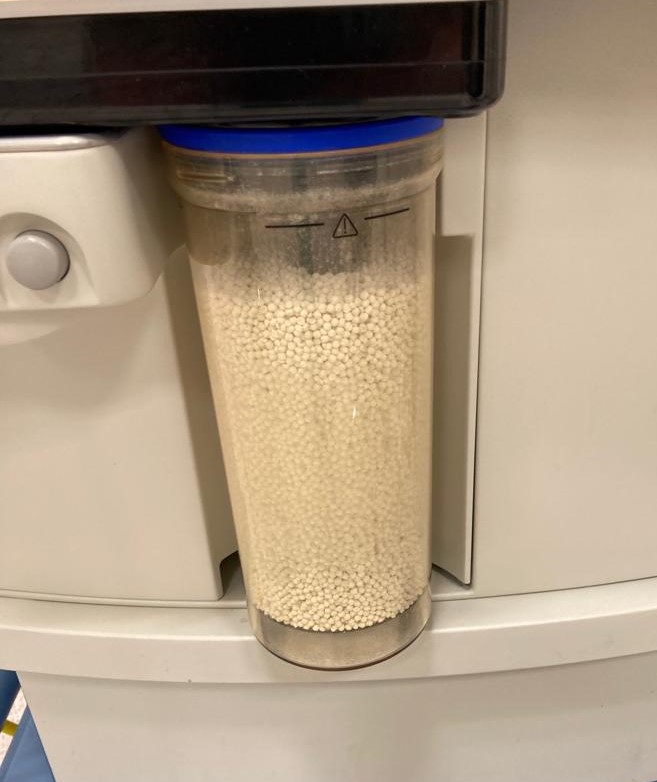

As the ‘circle system’ requires re-breathing of expired gases, carbon dioxide is actively removed from the circuit via a soda lime canister.

Suction apparatus

Suction apparatus is vital to safe medical practice in anaesthesia, resuscitation, and intensive care. It is used to clear mucus, saliva, blood and debris from the pharynx, trachea and main bronchi.

Suction apparatus requires an energy source that generates a ‘vacuum’. A true vacuum is rarely achieved as the pressure required is only a maximum of 60 kPa, less than normal environmental pressure!

The energy sources most commonly used are mains electricity and pipeline suction (where the suction is generated by an electrically powered vacuum pump at a distance from the user).

Portable suction units are also widely available in many clinical settings, including on resuscitation or ‘crash’ trolleys.⁴

Tip: Familiarise yourself with the local emergency equipment (as well as policies and procedures) whenever you start a new clinical placement or rotation!

Ventilators

Anaesthetic ventilators assist patients’ breathing during surgery or other procedures requiring anaesthesia.

A ventilator will generally be required for patients with endotracheal tubes or supraglottic devices (laryngeal mask airway / i-gel®) in place. Different ventilatory modes, such as pressure-controlled and volume-controlled, allow ventilatory support to be tailored to each patient.

The ventilator delivers a mixture of gases (oxygen and medical air) to the patient and a set concentration of volatile anaesthetic agent.

In addition to the ventilator integral to the anaesthetic machine, you may also see portable ventilators used. These standalone devices offer flexibility in various clinical settings (e.g. when transferring patients who require ventilatory support).³

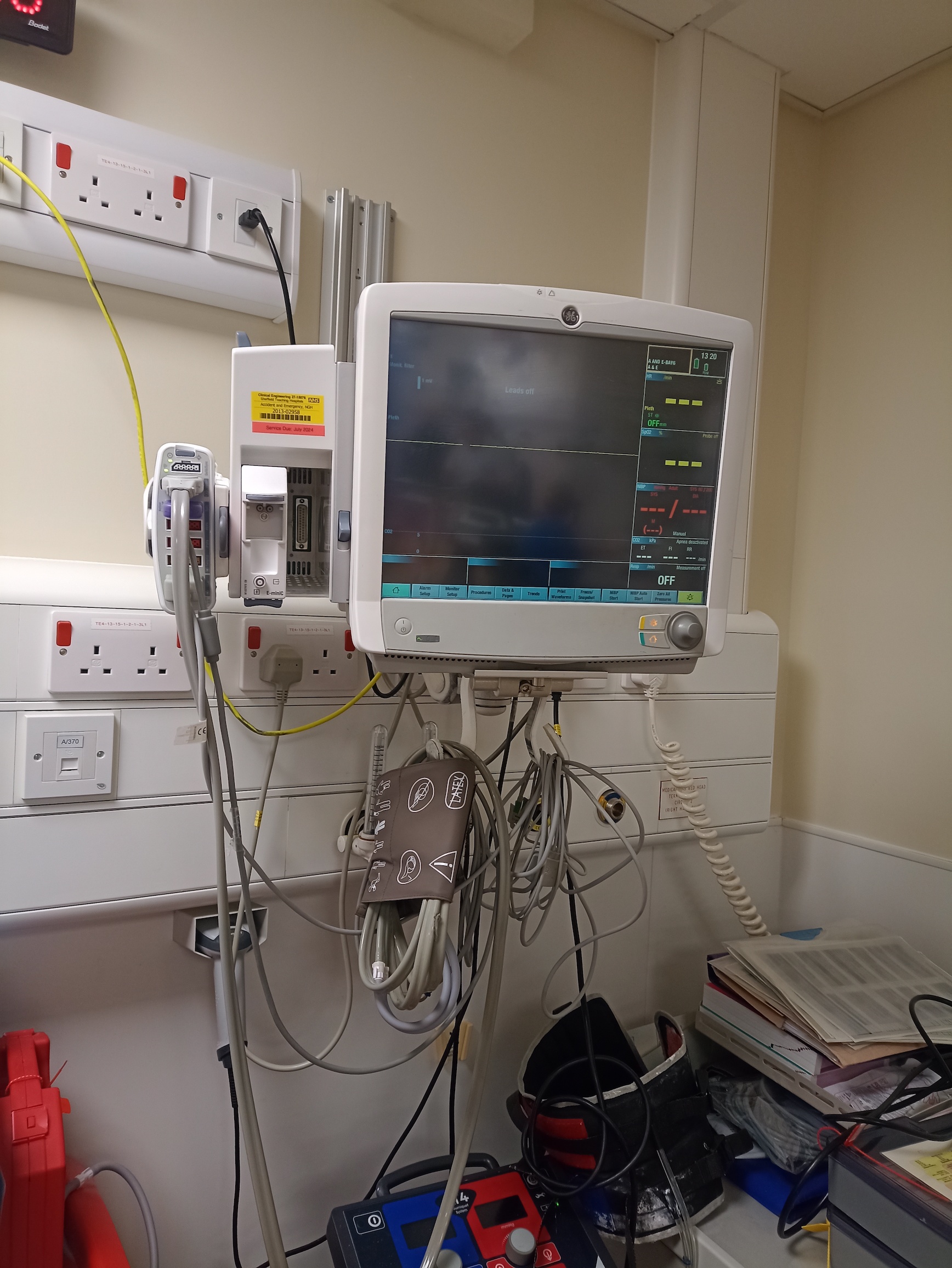

Patient monitoring equipment

Basic monitoring equipment used in anaesthesia includes:5

- Cardiac monitor to track heart rhythm and rate

- Pulse oximetry to give rapid and ongoing measurement of blood oxygen levels

- Non-invasive automated blood pressure monitoring

- Capnography to monitor carbon dioxide levels in exhaled breath

- Gas analysers in the anaesthetic machine to measure the concentration of inhaled and exhaled gases, as well as the respiratory rate

- Equipment to measure a patient’s temperature

Continuous cardiac monitoring and other parameters, such as oxygen saturation and blood pressure, provide a good overview of a patient’s cardiovascular status during anaesthesia.

A capnograph provides valuable information about a patient’s ventilatory status. By monitoring the end-tidal carbon dioxide levels, the capnograph can detect changes in ventilation, such as respiratory depression or obstruction.

Temperature monitoring is important in the perioperative environment as anaesthesia (and surgery) can affect the body’s ability to regulate temperature. Methods used to monitor temperature include tympanic thermometers and oesophageal probes. Identifying hypothermia allows anaesthetic staff to take measures, such as administering warm intravenous fluids or using warming blankets to maintain temperature within safe parameters.

Warming apparatus

Anaesthesia (and surgery) can increase a patient’s susceptibility to hypothermia, leading to complications such as longer recovery time, delayed wound healing, and higher infection rates. Vasodilation, reduced metabolic rate, and exposure to cool theatre environments (open wounds, laminar flow theatre ventilation) contribute to the development of hypothermia.⁶

Warming apparatus such as forced air warmers and intravenous fluid warmers are used in anaesthesia to help prevent hypothermia.

Forced air warmers deliver warm filtered air through a hose to a special blanket, creating a convective air current to warm the patient. A control unit sets, maintains, and monitors the desired temperature.

Cold intravenous fluids can cause a drop in body temperature, increasing the risk of hypothermia. To avoid this, fluids and blood products are warmed to body temperature before being administered.

There are many types of fluid warmers, and these are generally equipped with temperature controls and sensors to ensure fluids are heated to the appropriate temperature.

Infusion pumps

Various infusion pumps are used in anaesthesia to deliver controlled amounts of fluids, medications, and anaesthetic agents, and to ensure precise and timely administration of substances.

Infusion pumps typically have various modes, such as bolus dosing, continuous infusion, and patient-controlled analgesia (PCA).

Total intravenous anaesthesia (TIVA)

Total intravenous anaesthesia (TIVA) is an anaesthetic technique whereby all of the patient’s anaesthetic agents are delivered intravenously without the use of inhalational agents. Because of the need for careful and precise titration of medications used with this technique, it would be difficult or impossible to achieve without a good working knowledge of infusion pumps and their functions and capabilities.

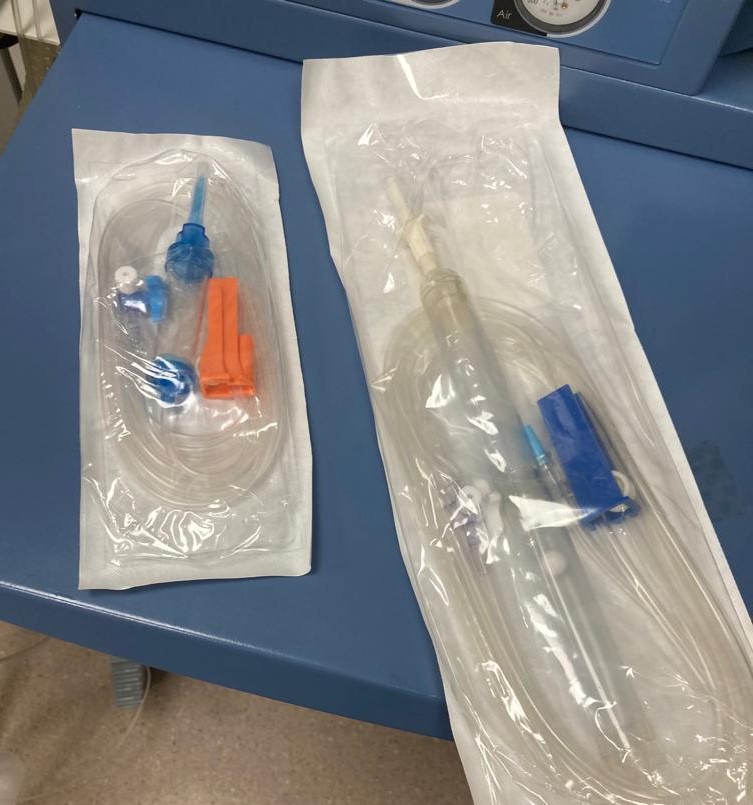

Giving sets (drip lines)

Giving sets are used in anaesthesia to deliver fluids (crystalloids and colloids), medications, and blood products to a patient. The main components of a giving set are:

- Drip chamber: a transparent chamber between the tubing and the spike, which allows visual monitoring of the flow rate

- Tubing: connects the fluid source (infusion bag/bottle) to the patient’s intravenous line; the tubing must be primed with fluid before connection to the patient’s cannula to prevent air from entering the patient’s bloodstream.

- Roller clamp: used to adjust the flow rate of fluid through the drip line

- Connectors: giving sets have connecting components that link the tubing to the patient’s intravenous cannula and the infusion source

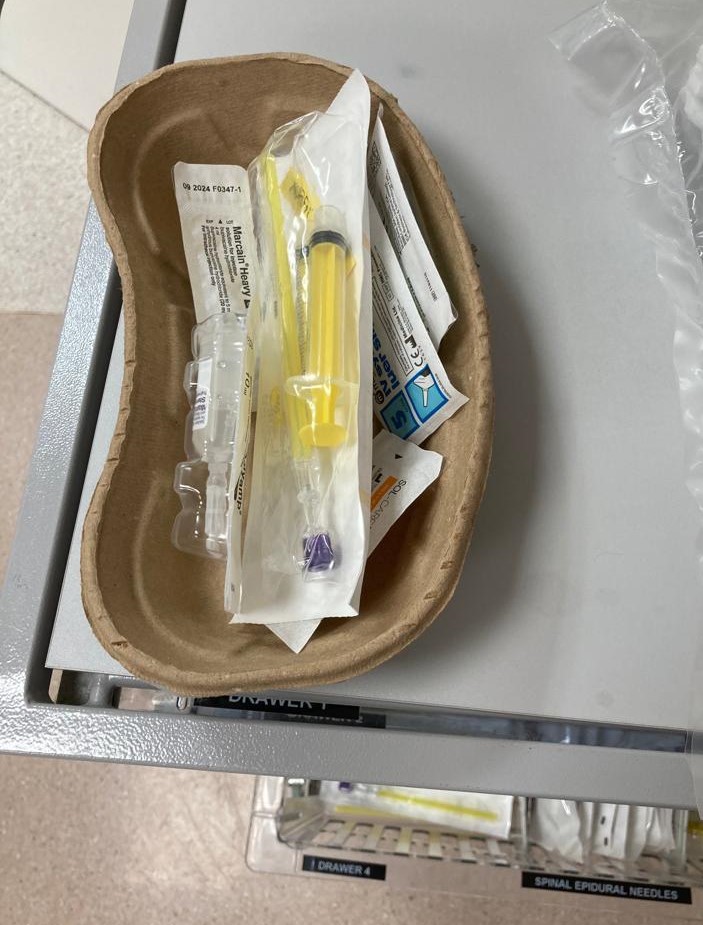

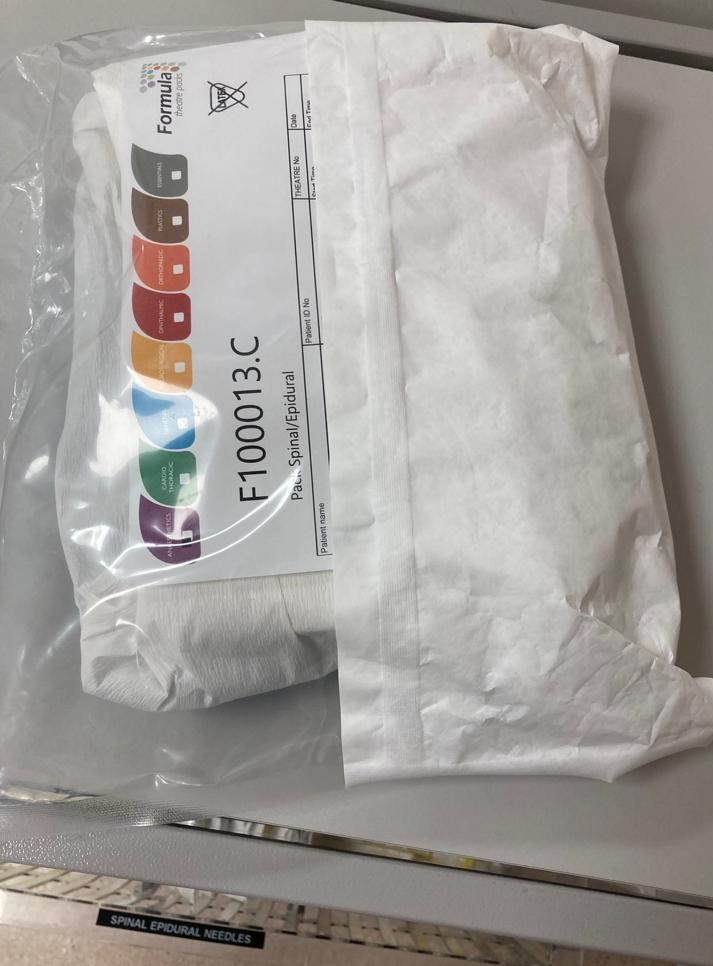

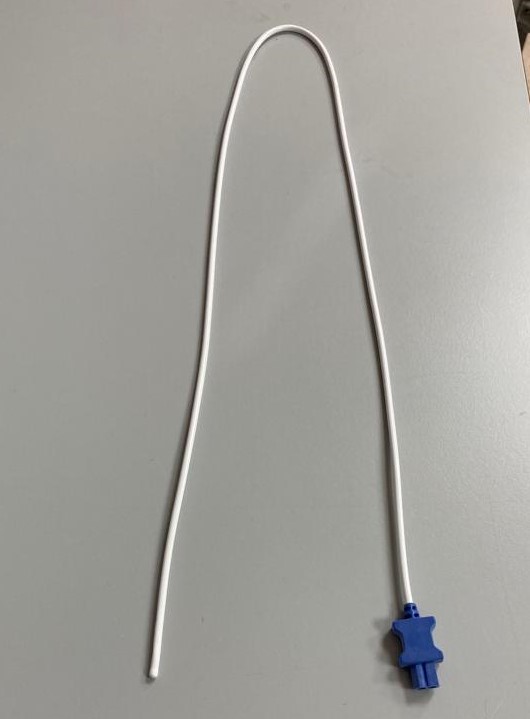

Neuraxial and regional anaesthesia equipment

Neuraxial anaesthesia (spinal and epidural) involves the injection of anaesthetic agents into the subarachnoid or epidural space to produce an anaesthetic block. This is performed to enable surgery to be carried out without the use of general anaesthesia, for pain relief, or both. Neuraxial and regional anaesthesia are also sometimes used in conjunction with a general anaesthetic.

Regional anaesthesia involves numbing a specific body part by injecting a local anaesthetic formulation around the nerves that supply that particular anatomical location. Sometimes known as a ‘nerve block’, this technique is often used for surgery involving the arms or hands, the abdomen, and the legs or feet.

The equipment used for neuraxial and regional anaesthesia may include hypodermic needles, syringes, local anaesthetic formulations, specialised needles, sterile drapes and gloves, and antiseptic solution.⁷ In addition, appropriate monitoring equipment must be available (blood pressure, pulse oximetry etc.). An ultrasound machine is often used when administering regional anaesthesia.

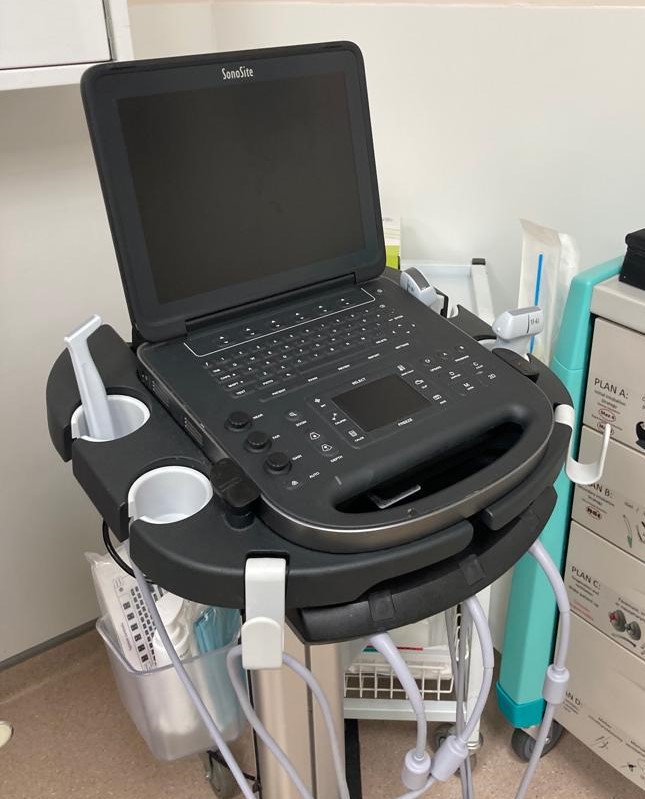

Ultrasound machine

Ultrasound technology is increasingly used in anaesthesia for procedures such as nerve blocks and for gaining vascular access. By providing an accurate and real-time visualisation of anatomical structures, ultrasound can help improve safety and accuracy.

Ultrasound aids in identifying and locating veins and arteries during peripheral vascular access, and when placing central/arterial lines. In regional anaesthesia, it helps locate specific nerves and surrounding structures for precise and safe delivery of local anaesthetic agents.

Reviewer

Andrea Menzel

Senior Operating Department Practitioner

Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- PerioperativeCPD. Anaesthetic machine back to front. Published in 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- Royal College of Anaesthetists. Preparing your theatre. Published in 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Sinclair CM, Thadsad MK, Barker I. Modern anaesthetic machines. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain, Volume 6, Issue 2, April 2006, Pages 75–78. Available from: [LINK]

- Herod R, Markham, R. Suction devices. Published in 2012. Available from: [LINK]

- Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Recommendations for standards of monitoring during anaesthesia and recovery. Published in 2015. Available from: [LINK]

- Bindu B, Bindra A, Rath G. Temperature management under general anaesthesia: Compulsion or option. Published in 2017. Available from: [LINK]

- Olawin AM, Das JM. Spinal anaesthesia. Published in 2022. Available from: [LINK]