- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

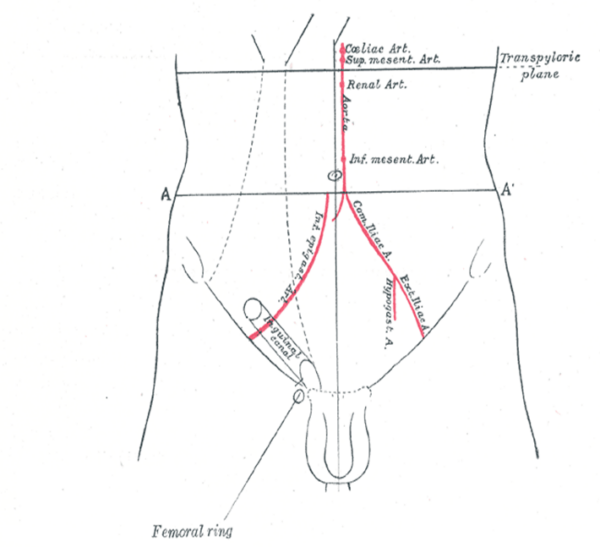

Introduction

The inguinal canal is a passage in the anterior abdominal wall that conveys several structures including nerves (ilioinguinal, genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve), spermatic cord (males) and round ligament (females). There is an inguinal canal present on both sides of the abdomen, running parallel to the inguinal ligament. At approximately 4cm length in adults, it begins with the deep inguinal ring posteriorly and then runs anteroinferiorly and medially until it meets the superficial inguinal ring.1,2

In this article, we will discuss the basic anatomy of the inguinal canal, including its contents, as well as inguinal hernias. For more information on hernias, see the Geeky Medics guide to inguinal and femoral hernias.

Borders of the inguinal canal

The borders of the inguinal canal can be recalled using the mnemonic MALT:2

- Muscles (roof)

- Aponeurosis (anterior wall)

- Ligaments (floor)

- Tendon (posterior wall)

Table 1. The borders of the inguinal canal

| Border | Contents |

|

Roof |

Transversus abdominis muscle, internal oblique muscle |

|

Anterior wall |

Aponeurosis of external oblique muscle |

|

Floor |

Inguinal ligament, lacunar ligament |

|

Posterior wall |

Conjoint tendon, transversalis fascia |

Deep inguinal ring

The deep inguinal ring is the start of the inguinal canal, arising just above the midpoint of the inguinal ligament, halfway between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle. It is oval-shaped and formed by an invagination of the transversalis fascia.

Superficial inguinal ring

The superficial inguinal ring lies above the pubic tubercle, marking the end-point of the inguinal canal. It is triangular-shaped, formed within the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle.1

Contents of the inguinal canal

The contents of the inguinal canal differ between males and females:

- Ilioinguinal nerve (L1): arises from part of the lumbar plexus and contributes to the sensation of the perineum and external genitalia. It pierces through the canal partway down and exits via the superficial inguinal ring. This makes it prone to damage during inguinal hernia repair.

- Genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve (L2): innervates the cremaster muscles in males as well as the mons pubis and labia majora in females.

- The round ligament of the uterus (females): attaches to the labia majora and functions as an anchor to keep the uterus anteverted.

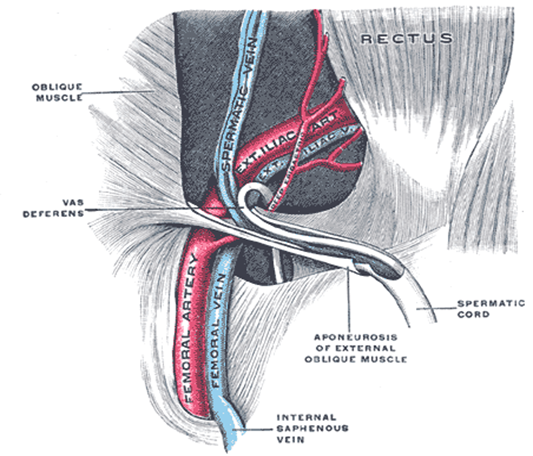

- Spermatic cord (males): contains many layers of fascia, arteries, nerves and reproductive structures

The spermatic cord

The spermatic cord is the main structure passing through the inguinal canal in males. Although the contents are complex, a simple way to remember them is by using the ‘rule of 3’:2

- 3 fascial layers: external spermatic fascia, cremasteric fascia/ muscle, internal spermatic fascia

- 3 arteries: artery to vas (ductus) deferens, cremasteric artery, testicular artery

- 3 nerves: ilioinguinal nerve, genital branch of genitofemoral, sympathetic and visceral afferent nerve fibres

- 3 other: pampiniform plexus, vas deferens, testicular lymphatics

Embryology

In early development, the gonads (testes/ovaries) develop on the posterior abdominal wall.

The inguinal canal acts as a conduit for the testes to descend into the scrotum. The gubernaculum, a fibrous piece of tissue, attaches to the inferior pole of the gonads and helps guide their descent into the scrotum/pelvis. As they descend, they also follow the path of the processus vaginalis, an outpouching of the peritoneum through the anterior abdominal musculature.

As the processus vaginalis migrates, it takes layers of the abdominal wall with it, creating the inguinal canal. The processus vaginalis should degenerate, however, failure to do so can result in an indirect inguinal hernia or failure of the testes to descend (cryptorchidism).

Clinical relevance: inguinal hernias

An important and common clinical application of the inguinal canal is the occurrence of inguinal hernias, where part of the peritoneal sac protrudes through a weakened part of the abdominal wall.

These are far more common in males due to the larger size of the inguinal canal, however, a host of other factors can predispose individuals to developing a hernia.

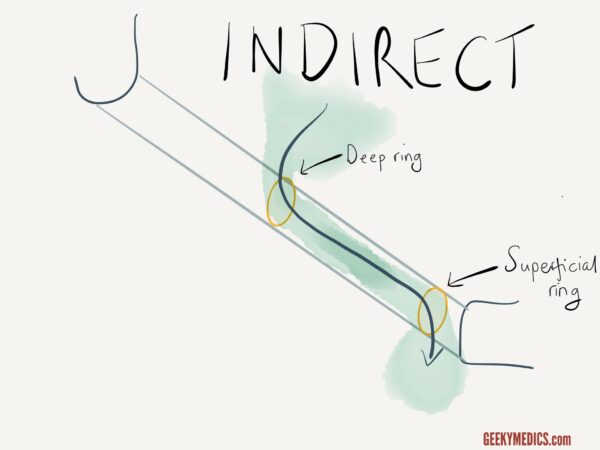

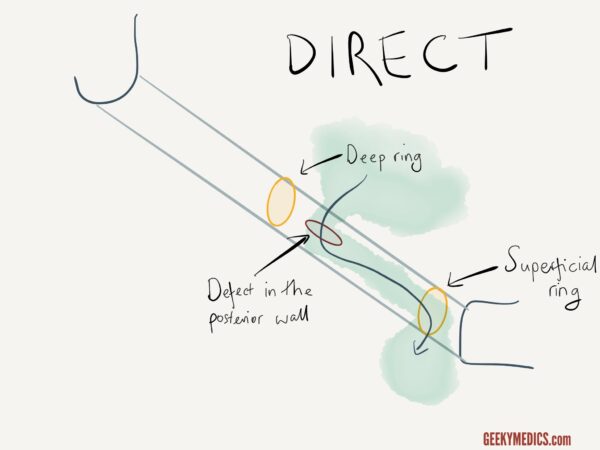

Inguinal hernias can be direct or indirect:

- Indirect: peritoneal sac enters the inguinal canal through the deep inguinal ring, usually this is caused by a congenital defect where the processus vaginalis remains patent. If the peritoneum is able to transverse the entire inguinal canal, then these hernias can present as lumps in the scrotum or labia majora. This type of hernia is the most common of the two.

- Direct: peritoneal sac enters the inguinal canal through a weakened part of the posterior wall of the canal, usually acquired due to weakened musculature with age and are common in older men.

For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to inguinal and femoral hernias.

Key points

- The inguinal canal acts as a communication channel for abdominal contents with the external genitalia.

- In early development, the inguinal canal plays a crucial role in allowing the gonads to descend, most notably the testes into the scrotum.

- Significant variation in contents occurs between male and female anatomy.

- An important clinical application is the development of inguinal hernias, they can be either direct or indirect, depending on whether they enter the inguinal canal through the deep inguinal ring or a muscular defect in the abdominal wall.

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Richard L Drake (Richard Lee), Wayne Vogl, Adam W. M. Mitchell. Gray’s anatomy for students, Published 2020. Fourth edition.

- Lorenzo Crumbie. Inguinal canal. Published November 13th Available from: [LINK]

- Henry Vandyke Carter and Henry Gray, Anatomy of the Human Body, Published 1918. License: [Public domain]

- Henry Vandyke Carter and Henry Gray, Anatomy of the Human Body, Published 1918. License: [Public domain]

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health. Inguinal Hernia. License: [Public domain]