- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Testicular torsion refers to the twisting of the spermatic cord within the scrotum. This leads to occlusion of testicular venous return and subsequent compromise of the arterial supply, resulting in ischaemia of the testis.1

Testicular torsion is a urological emergency. Permanent ischaemic damage may occur within 4-8 hours and urgent surgical intervention is required.2

Aetiology

Anatomy

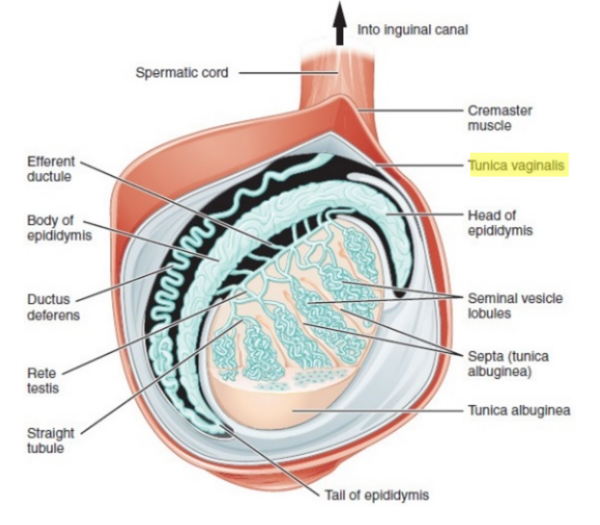

The testes lie within the scrotum in a vertical position with the help of the spermatic cord, which arises from the abdomen.

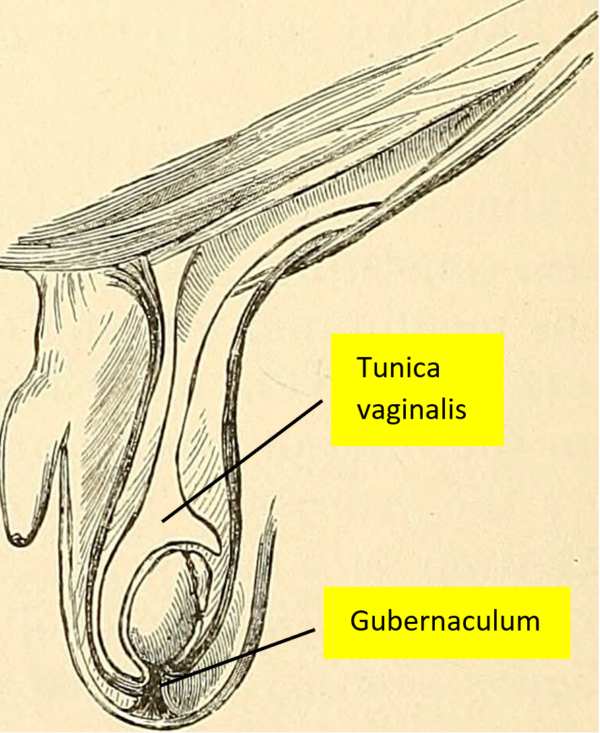

The spermatic cord carries a collection of vessels, nerves and ducts to supply the testes. The tunica vaginalis is a closed sac from the parietal peritoneum which encloses and holds the posterolateral portion of the testes and epididymis in place. Similarly, the gubernaculum fixes the testes but does so at the base of the scrotum (Figure 1 and 2).4-5

Causes of testicular torsion

There are two mechanisms for testicular torsion, intravaginal and extravaginal.

Intravaginal

Intravaginal torsion occurs due to a lack of fixation of the posterolateral section of the testis to the inner wall of the scrotum.

This occurs due to a higher than usual attachment point of the tunica vaginalis to the testis and epididymis within the sac. Hence, the testes swing and rotate freely within the tunica vaginalis. This leads to the formation of the bell-clapper deformity, a free-moving cord inside the scrotum that resembles a ‘clapper in a bell.’

Extravaginal

Extravaginal torsion is rare but more commonly seen in neonates before the gubernaculum can fixate the testes to the bottom of the scrotum embryologically. This leads to torsion of the testis, the tunica vaginalis and the spermatic cord together. This typically occurs in or just below the inguinal canal.

Whether the mechanism is intravaginal or extravaginal, the torsion of the spermatic cord will increase venous pressure and congestion, which then leads to a decrease in arterial blood flow and subsequent ischaemia.6

Torsion of the hydatid of Morgagni

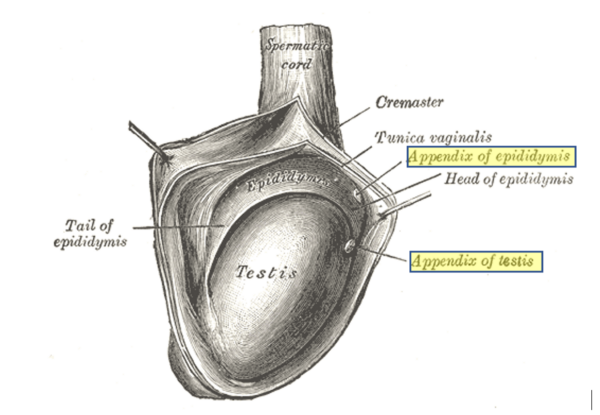

An important differential of testicular torsion is torsion of the testicular or epididymal appendix.

These structures are embryological remnants that can become torted, leading to an acute scrotum. The testicular appendage, also called the hydatid of Morgagni, is a remnant of the Mullerian duct. It is located on the superior pole of the testis.

The epididymal appendage is a Wolffian duct remnant and is rarely identified in patients. It is located alongside the head of the epididymis (Figure 3).

(with the appendix of testis and appendix of epididymis highlighted)16

Risk factors

Testicular torsion is most common in neonates and pubertal boys but can occur in males of all ages. The peak incidence is between the ages of 10-14 years.3

There is typically no precipitating event, however, risk factors may include:7

- Cryptorchidism (undescended testes)

- Pubertal changes (increase in testicular volume)

- Testis with a horizontal lie

- Previous testicular tumour

- Bell-clapper deformity

- Recent strenuous exercise

- Previous testicular torsion

- Family history of testicular torsion

Clinical features

History

Acute scrotal pain should be treated as testicular torsion until proven otherwise.

Typical symptoms of testicular torsion include:8

- Sudden onset, severe unilateral testicular pain

- Lower abdominal pain

- Nausea and vomiting

Other important areas to cover in the history include:

- The presence of risk factors for torsion (see risk factors section)

- Past surgical history: scrotal surgery

- Sexual history (if appropriate)

- History of previous testicular pain: intermittent episodes of testicular pain may suggest intermittent torsion

Clinical examination

In the context of a suspected testicular torsion, a thorough male genital examination should be performed.

Typical clinical findings on testicular examination may include:

- Inflammatory signs of one testis: swollen, tender and erythematous scrotal skin

- Lie of the testis might be horizontal (in a ‘bell-clapper’ position) and high riding/elevated in the neck of the scrotum

- Pain may not be relieved on elevating the affected testis (known as a negative Prehn’s sign). However, this test cannot reliably distinguish testicular torsion from other causes of testicular pain.

- Absent cremasteric reflex: this is performed by stroking the inner thigh to elicit whether the L1/2 spinal reflex causes an upward movement of the scrotal contents.

Other clinical findings may include:

- In early torsion, the spermatic cord may be palpated. However, in severe cases, palpation may be difficult due to scrotal oedema.

- In neonatal torsion, the patient may be asymptomatic, and present as a firm, hard and enlarged testis in a blue scrotum.

Differential diagnoses

Table 1. Differential diagnoses for an acute scrotum with characteristic differentiating features from testicular torsion.

| Differential diagnosis | Characteristic differentiating features |

| Acute epididymitis/epididymo-orchitis |

|

| Torsion of testicular or epididymal appendage (the hydatid of Morgagni) |

|

| Idiopathic scrotal oedema |

|

| Inguinal hernia |

|

| Hydrocoele |

|

| Testicular tumour |

|

Investigations

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations include:

- Urinalysis: to look for evidence of a urinary tract infection (however, an abnormal urinalysis does not rule out testicular torsion)

Imaging

Relevant imaging investigations include:

- Doppler ultrasound scan: this may demonstrate a lack of blood flow to the testis, indicating torsion. However, investigations and imaging should not delay surgical exploration for a suspected testicular torsion.

Surgical exploration

Surgical exploration can confirm the diagnosis of testicular torsion. Timing is essential as torsion for greater than four hours may lead to irreversible damage/death of the testicular tissue.12

Management

Urgent surgical intervention is the key to managing testicular torsion and preventing permanent ischaemic damage.

Manual detorsion

Manual detorsion may be performed if the patient presents early or whilst waiting for surgical exploration.

This involves manually rotating the affected testicle from the medial to the lateral position (as though opening a book), as this is how testicles are usually twisted. This can be done with or without local anaesthesia.

If this is successful there may be a dramatic improvement in the patient’s pain, however, this is only a temporary measure.

Surgical exploration

Surgical exploration is performed under general anaesthetic. This involves a possible bilateral orchidopexy (fixation) or orchidectomy (removal of testis).

An incision is made over the scrotum and the testis is removed from the scrotal sac. The testis is de-torted and its’ colour observed. If the testis has a red tinge and looks viable it may be sutured to the tunica vaginalis and returned to the scrotum in the correct orientation. If the testis remains dusky or looks black, an orchidectomy will likely be performed.

Fixation of the testes is performed bilaterally, as the Bell-clapper abnormality may be present bilaterally. Thus, fixation of the affected and the unaffected testes is performed prophylactically.7

Post-operatively, if the testis is saved, the patient must be provided with scrotal support and advised to remain on bed rest for 24 hours. Patients should also be advised to refrain from any heavy lifting or exercise for the first few weeks.9,13

Complications

If testicular torsion is not identified and treated urgently, complications can include:

- Atrophy or necrosis (death) of the testis

- Infection

- Subfertility: however, if the contralateral testis is functioning, fertility may not be affected

Key points

- Testicular torsion is the twisting of the spermatic cord within the scrotum. It is a urological emergency requiring urgent surgical intervention.

- It can either be due to an intravaginal (‘bell-clapper deformity’) or extravaginal cause.

- Risk factors include cryptorchidism, horizontally-lying testes, and testicular tumours.

- Acute scrotal pain in all prepubertal and young adult males should be managed as testicular torsion until proven otherwise.

- The most common symptoms include severe pain in one testis, sometimes accompanied by lower abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting.

- The most common exam findings include a red, swollen and tender testis, in a horizontal line, high up in the scrotum. This may be accompanied by a negative Prehn’s sign and an absent cremasteric reflex.

- Doppler ultrasound scan may be considered if available, but surgical exploration should not be delayed for imaging.

- Treatment may involve manual detorsion and a possible orchidectomy + bilateral orchidopexy.

- Untreated, complications include necrosis and subsequent loss of the torted testis.

Reviewer

Elizabeth Cotzias

Surgery Registrar

Editors

Dr Chris Jefferies

Hannah Thomas

References

- Patient.info. Torsion of the Testis. Published in 2016. [LINK]

- Ian B. Wilkinson, Tim Raine, Kate Wiles, Anna Goodhart, Catriona Hall and Harriet O’Neill. Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine 10th Surgery. Published in 2017. [LINK]

- Huang W, et al. The incidence rate and characteristics in patients with testicular torsion: a nationwide, population-based study. Published in 2013. [LINK]

- Patel AP. Anatomy and physiology of chronic scrotal pain. Published in 2017. [LINK]

- Tiwana MS, Leslie SW. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Testicle. Published in 2020. [LINK]

- American Family Physician. Testicular Torsion: Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Management. Published in 2013. [LINK]

- American Family Physician. Testicular Torsion. Published in 2006. [LINK]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Scrotal pain and swelling. Published in 2019. [LINK]

- Taylor SN. Epididymitis. Published in 2015. [LINK]

- American Family Physician. Epididymitis: An Overview. Published in 2016. [LINK]

- American Family Physician. Epididymitis and Orchitis: An Overview. Published in 2009.

- GP Notebook. Testicular torsion. [LINK]

- British Association of Urological Surgeons. Scrotal Exploration for Suspected Torsion of the Testis. Published in 2017. [LINK]

- Gray, Henry, 1825-1861 Pick, T. Pickering (Thomas Pickering), 1841-1919, ed Keen, William W. (William Williams), b. 1837. Diagram to illustrate the Descent of the Testis and the Formation of the Tunica Vaginalis. [CC BY-SA] [LINK]

- OpenStax College. Illustration of testicle. [CC BY-SA] [LINK]

- Henry Gray. The right testis, exposed by laying open the tunica vaginalis. [CC BY-SA] [LINK]