- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Bladder cancer is the most common urinary tract tumour and the 11th commonest cancer in the UK. Around 10,300 new cases are diagnosed yearly, with 5,600 deaths per year and a higher incidence in males than females.1

Patients often present early with painless visible haematuria. Most bladder cancers at diagnosis (75-80%) have not progressed to invade the bladder muscle.2

Aetiology

The urinary bladder, as well as the ureter and proximal urethra, is lined with a specialised stratified epithelium termed the urothelium (or transitional epithelium).

As the bladder becomes distended with urine, the urothelial layer becomes flattened under pressure and results in increased exposure to environmental chemicals in the urine that could lead to mutation.3 This results in a urothelial (or transitional cell) carcinoma, which accounts for 90% of bladder cancers in developed countries.

Squamous cell carcinoma makes up a further 5% of cases and is linked to conditions that cause prolonged inflammation within the bladder. This is more commonly seen in Africa and Asia due to infection with the parasite Schistosomiasis. However, it is also linked to recurrent urinary tract infections and long-term catheters.

The remaining histological subtypes comprise adenocarcinoma (2%) and other rare cases (e.g. sarcomas, small cell carcinomas).4

Risk factors

The main risk factors for bladder cancer are increasing age and smoking.5

Other risk factors include:

- Male sex: 3:1 increased risk compared to females

- Occupational exposure to aromatic amides: found in industrial settings that process rubber, dyes, textiles, paints, and solvents

- Pelvic radiation

- Cyclophosphamide

- Chronic inflammation from infection or indwelling catheters (squamous cell tumours)

- Schistosomiasis (squamous cell tumours)

Clinical features

Painless, visible haematuria is the presenting complaint in 80-90% of patients and may be the only symptom.5

Other symptoms may include:

- Non-visible haematuria: around half as likely to be linked to bladder cancer as visible haematuria

- Difficulty passing urine

- Change to urinary frequency and/or urgency

- Recurrent urinary tract infections

- Pelvic pain

- Back pain

- Weight loss

- Fatigue

Referral for suspected bladder cancer6

Patients should be referred to a suspected cancer pathway (to be seen within two weeks) for bladder cancer if they are:

Aged 45 and over with either:

- Unexplained visible haematuria without urinary tract infection

- Visible haematuria that persists or recurs after successful treatment of a urinary tract infection

Aged 60 and over with:

- Unexplained non-visible haematuria and either dysuria or a raised white cell count

Differential diagnoses

The differential diagnosis for bladder cancer includes other common causes of haematuria.

Table 1. Differential diagnoses for bladder cancer.5

| Differential diagnosis | Clinical features |

| Urinary tract infection |

|

| Renal cell carcinoma |

|

| Prostate cancer |

|

| Benign prostatic hyperplasia |

|

| Renal calculi |

|

| Radiation cystitis |

|

Investigations

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations include:

-

Urinalysis and urine culture: to exclude infection

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:

- Full blood count: to check haemoglobin for evidence of anaemia

- Renal function

- Urine cytology: detects abnormal cells within the urine, although it has a low sensitivity for bladder cancer, so is used in conjunction with cystoscopy

Cystoscopy

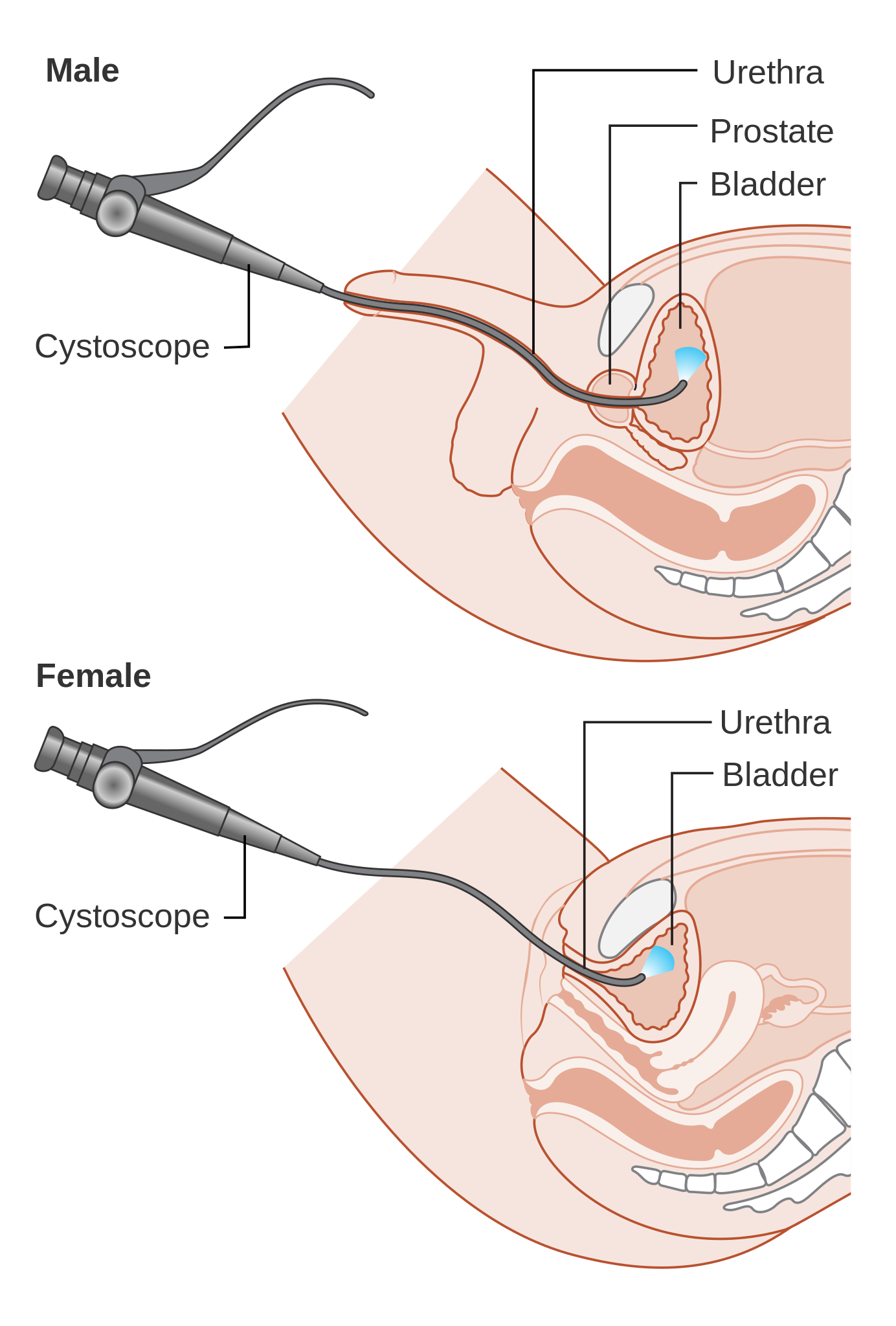

All patients with a suspected bladder tumour should be offered urgent cystoscopy.

The first line is usually a flexible cystoscopy, as it can be tolerated when the patient is awake with local anaesthetic gel (the procedure is similar to a catheter insertion). This allows direct visualisation of the internal surface of the bladder and the ability to locate any suspicious lesions.

Imaging

NICE guidelines recommend considering a CT or MRI staging scan if the patient is suspected of having muscle-invasive bladder cancer after their cystoscopy.

A CT urogram is also useful for detecting possible lesions in the ureters. 8

Diagnosis

For a complete diagnosis of bladder cancer, a sample must be sent for histological analysis. To achieve this, the lesion is removed via a transurethral resection of bladder tumour (TURBT).

The procedure is performed under general anaesthetic and involves a rigid cystoscope being passed through the urethra into the bladder. The suspicious mass(es) are then located, removed, and sent for histological analysis.

Removing the lesion should also include a sample of the underlying muscle tissue to check for muscle invasion. If no muscle is involved in the original sample, the patient requires further TURBT to obtain a muscle sample.

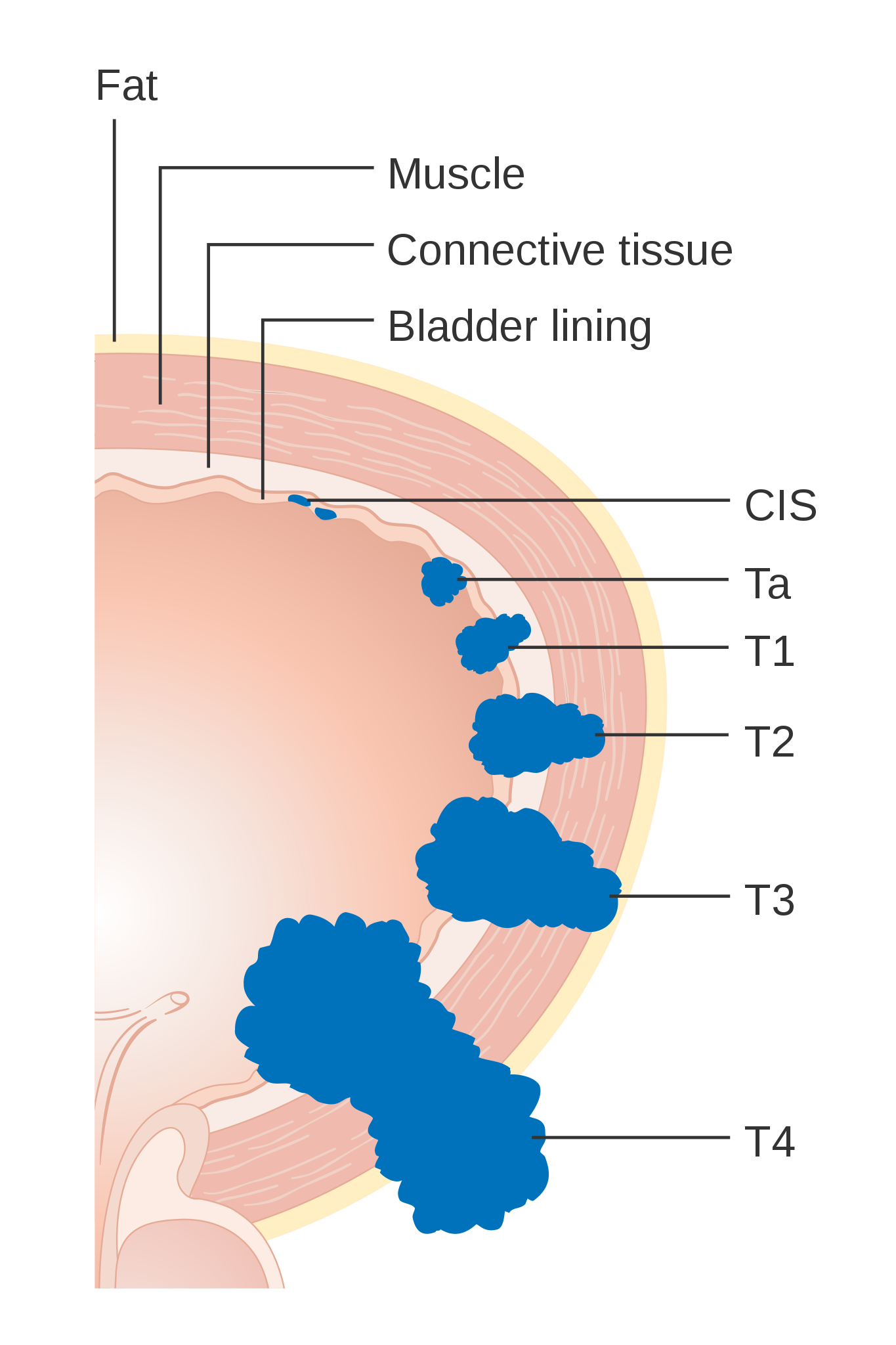

Paired with CT imaging, the histology results can then be used for staging and subsequent management. The tumour, lymph node, metastasis (TNM) staging system is used for bladder cancer (Table 2).

Table 2. TNM staging for bladder cancer.9

| T – Primary tumour | N – Lymph nodes | M – Metastasis |

| Ta: non-invasive papillary carcinoma | Nx: unable to assess regional lymph nodes | MX: Metastasis not assessed |

| Tis: Carcinoma in situ (flat tumour) | N0: no regional lymph nodes involved | M0: No distant metastasis |

| T1: invades subepithelial connective tissue | N1: Metastasis in a single lymph node in the true pelvis | M1: Distant metastasis |

| T2: Invades muscularis | N2: Metastasis to multiple lymph nodes in the true pelvis | |

| T3: Invades through the muscle | N3: Metastasis in the common iliac nodes | |

| T4: Invades surrounding structures (e.g. prostate, uterus, pelvic wall) |

Urothelial carcinomas are also graded either low or high grade or into grades 1-3 based on the level of differentiation. The more differentiated the cells are, the higher the grade, the more aggressive the tumour is likely to be.9

Management

Management of bladder cancer depends on whether the tumour is muscle-invasive or non-muscle-invasive, and should always involve multidisciplinary team (MDT) discussion.

Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer

Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer consists of Ta (non-invasive papillary carcinomas), Tis (carcinoma in situ), and T1 (invading the subepithelial tissue but not involving the muscle).

Patients are divided into low, intermediate, and high risk depending on size and grade with corresponding treatment plans (Table 3).11

Table 3. Management of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer 11

| Low risk | Intermediate risk | High risk |

| No immediate treatment after initial TURBT | 6 doses of intra-vesicle chemotherapy (mitomycin C) following initial TURBT | Repeat TURBT within 6 weeks from initial TURBT |

| Check cystoscopy in 3 and 12 months after initial TURBT | Check cystoscopy at 3, 9, and 18 months after completion of chemotherapy, followed by annual checks for 5 years | Course of BCG followed by check cystoscopy every 3 months for the first 2 years, 6 months for a further 2 years, then annually |

| If a lesion is seen at check cystoscopy, refer for repeat TURBT If no lesions, then discharge |

If a tumour recurs following BCG, or treatment not tolerated, then a cystectomy should be considered |

Muscle-invasive bladder cancer

Patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer are offered neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radical treatment.

Radical treatment options include:

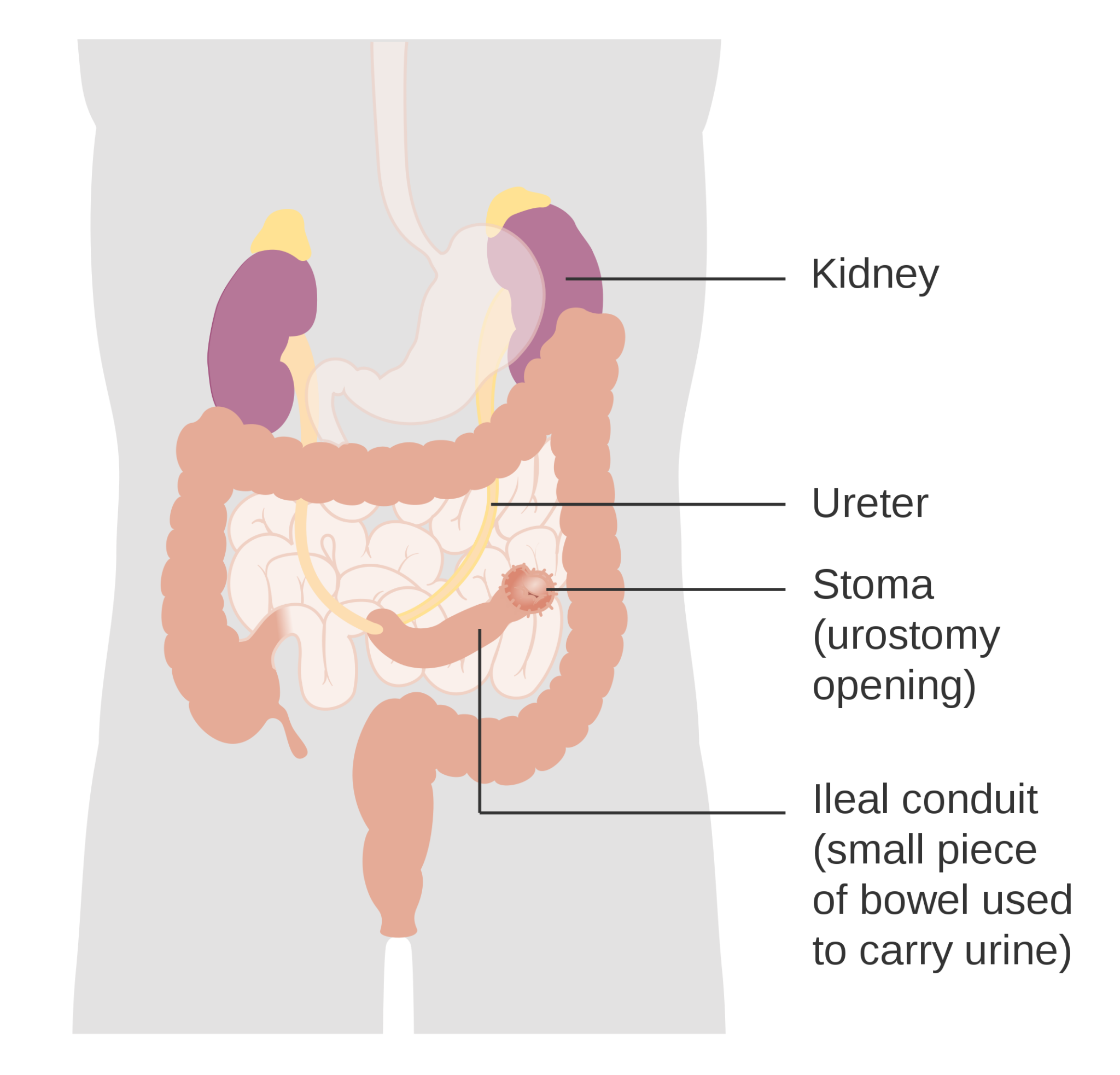

- Radical cystectomy with a urinary stoma (ileal conduit/urostomy) or continent urinary diversion (e.g. bladder substitution or catheterisable reservoir); estimated 5-year survival 40-60%.

- Radical radiotherapy: for patients who are unsuitable or do not wish to have a cystectomy; estimated 5-year survival rate 40%.

However, modern bladder-conserving approaches now recommend a “trimodal therapy” consisting of TURBT, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy with a similar prognosis to radical cystectomy.

Follow-up depends on the management used:8

- Radical cystectomy: CT chest, abdomen, and pelvis (CAP) 6, 12, and 24 months postoperatively, as well as annual eGFR, B12, and folate checks

- Radical radiotherapy: cystoscopy every 3 months for 2 years, 6 months for 2 years, then annually as well as CT CAP at 6, 12, and 24 months

Complications

It is important to be aware of complications of disease progression, metastatic spread of bladder cancer, and potential complications from surgical management.

Complications from invasive disease and metastatic spread include:5

- On-going urinary symptoms (e.g. haematuria, urinary incontinence, dysuria, urinary frequency)

- Loin pain and ureteric obstruction

- Hydronephrosis

- Intractable haematuria: especially if the patient has received radiotherapy

- Pelvic pain

Complications of TURBT include:14

- Failure to fully remove the lesion

- Infection

- Bleeding

- Bladder perforation

- Damage to the ureters

- Damage to the ureter

Prognosis

Patients with superficial tumours have a five-year survival rate of 80-90%. However, the recurrence rate for superficial urothelial carcinoma is around 70% within five years.

Those with muscle-invasive bladder cancers have a five-year survival rate of 30-60%, which drops to 10-15% if metastatic disease is present.5

Key points

- Bladder cancer is the 11th most common cancer in the UK, with transitional cell carcinoma forming the majority of cases

- The most common patient presentation is painless, visible haematuria

- Diagnosis is achieved through visualisation with cystoscopy, staging with CT, removal via TURBT, and histological analysis

- Non-muscle invasive bladder cancers are usually treated with tumour removal +/- intra-vesicle chemotherapy, and surveillance

- Muscle-invasive bladder cancers are usually managed with chemotherapy and either radical cystectomy or radiotherapy

- The 5-year survival rate for non-muscle invasive disease is 80-90% and 30-60% for muscle-invasive disease

Reviewer

Miss Emer Hatem

Urology Registrar

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Cancer Research UK. Bladder Cancer Statistics. Published in 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Bladder cancer: diagnosis and management: Introduction. Published in 2015. Available from: [LINK]

- Bolla SR, Odeluga N, Amraei R, et al. Histology, Bladder. Published in 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- Cancer Research UK. Types of bladder cancer. Published in 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- Knott, L. Bladder Cancer. Published in 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Referral for suspected urological cancer. Published in 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- Cancer Research UK. Diagram showing a cystoscopy for a man and a woman. License CC BY-SA 4.0 [LINK]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Bladder cancer: diagnosis and management: Recommendations. Published in 2015. Available from: [LINK]

- Cancer Research UK. Grades of bladder cancer. Published in 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- Cancer Research UK. Diagram showing the T stages of bladder cancer. License CC BY-SA 4.0 [LINK]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Bladder cancer: diagnosis and management: Treating non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Published in 2015. Available from: [LINK]

- Premo C, Apolo AB, Agarwal PK, et al. Trimodality therapy in bladder cancer: Who, what and when? Published in 2015. Available from: [LINK]

- Cancer Research UK. Diagram showing how urostomy is made (ileal conduit). License CC BY-SA 4.0 [LINK]

- British Association of Urological Surgeons. Transurethral telescopic resection of a bladder tumour. Published in 2022. Available from: [LINK]