- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Renal colic describes intense wave-like pain related to the passage of ureteric stones. It is a very common condition, with an estimated 12% of men and 6% of women experiencing renal colic at least once in their lifetime1. Most stones are calcium-based (oxalate, phosphate or mixed). Other stones include urate, struvite and cysteine.

The following article will cover the assessment, investigation and management of patients with ureteric stones. Please note, we do not cover the management of nephrolithiasis (the presence of stones in the kidney).

Aetiology

The aetiology of kidney stones is multifactorial. They have no definite single cause, and for most patients, a combination of both patient and environmental risk factors can predispose to the formation of calculi.

The urinary system involves the kidneys, ureters, bladder and urethra. Patients who present with renal colic will have built-up calculi over time in the kidney. Renal calculi do not ordinarily cause pain when they remain in the kidney. However, when those kidney stones drop into the ureters, it can be excruciating. Importantly, the stones may also obstruct the urinary system.

Obstruction of a ureter can be life-threatening to patients. The stasis of urine in a blocked kidney can lead to superimposed infection, which can cause rapid-onset sepsis. Calculi often obstruct the ureters at three anatomical points:

- The pelvic ureteric junction (PUJ): the junction between the renal pelvis and ureter

- The pelvic brim: where the ureter crosses above the common iliac vessels into the pelvis

- The vesicoureteric junction (VUJ): the junction between the ureter and bladder

The pain from ureteric calculi is colicky. This is from reflex spasms of the ureter as the stone passes through. Micro-abrasions caused by a hard stone passing through the ureter cause microscopic (non-visible) haematuria (blood in the urine).

Anatomically, the ureter lies close to the genitofemoral nerve (a branch of the lumbar plexus). This proximity can cause referred testicular pain (hence the characteristic description of ‘loin to groin’ pain).

80% of renal calculi are calcium-based. These include calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate and mixed calcium stones. Struvite stones make up 10%, uric acid stones make up 9%, and cysteine stones form approximately 1%.

Risk factors

Risk factors for the formation of kidney stones include:

- Dehydration: perhaps the most important modifiable risk factor

- Previous stones or family history of stones

- Metabolic conditions (e.g. cystinuria, primary hyperparathyroidism, gout etc.)

- Medications including diuretics, antiretrovirals and antacids predispose to stone formation

- Obesity

- Bowel conditions (e.g. inflammatory bowel disease)

- Idiopathic (most stones)

Clinical features

History

Typical symptoms of renal colic include:

- Sudden onset, severe, loin-to-groin pain: will wake patients up from sleep and come on in ‘waves’ (colicky pain), patients typically describe a sharp pain that moves up and down from flank to groin

- Nausea

- Systemic symptoms (fever/rigors): suggests an infected, obstructed system

Episodes of colicky pain can vary substantially in their duration, from seconds to hours. It is also difficult to predict the duration between episodes. For patients with an infected, obstructed system, the pain can be constant.

Colic patients typically cannot lie still. This can be a differentiating factor when comparing pain from renal colic and peritonism.

Other important areas to cover in the history include:

- Past medical history: previous stones or metabolic conditions (cystinuria, primary hyperparathyroidism, gout etc.)

- Drug history: diuretics, antiretrovirals, and antacids can contribute to the formation of stones

- Family history

- Social history: smoking status (a risk factor for stone formation), fluid intake, occupation (heavy machinery operators or pilots will not be able to work until the stone is treated)

For more information, see the Geeky Medics OSCE guide to urological history taking.

Clinical examination

All patients with suspected renal colic should undergo an abdominal examination to exclude complications (e.g. infected obstructed system) or important differential diagnoses (e.g. a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurism).

Typically, patients with renal colic will have an unremarkable abdominal examination.

Severe, unilateral flank pain on palpation can indicate an infected urinary system.

Differential diagnoses

When considering severe unilateral abdominal or flank pain, it is important to consider a wide range of diagnoses.

Table 1. Differential diagnoses to consider when assessing a patient with abdominal pain.

| Differential diagnosis | Clinical features |

|

Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm 🚩 Do not miss this diagnosis |

These patients may present as haemodynamically unstable, but others may have more subtle signs, such as an acute kidney injury. This diagnosis should always be considered in older men with risk factors (e.g. smoking) |

|

Abdominal +/- pelvic pain +/- vaginal bleeding. May present acutely in shock. Always check a urinary HCG in women of reproductive age. |

|

|

Ovarian torsion |

Intermittent iliac fossa tenderness. |

|

Tubuloovarian abscess |

Severe constant iliac fossa tenderness which can mimic appendicitis. These patients may be systemically unwell. |

|

Severe sudden onset unilateral testicular tenderness, which can radiate to the abdomen |

|

| Right-sided pain | |

|

Biliary colic |

Intermittent pain right upper quadrant pain classically related to fatty food. |

|

Cholecystitis |

Constant pain with positive Murphy’s sign (unable to take a deep breath in when palpating the right upper quadrant of the abdomen) |

|

A triad of fevers, right upper quadrant pain and jaundice |

|

|

Portal vein thrombosis |

Severe right upper quadrant pain, often with jaundice |

|

Right iliac fossa tenderness with raised inflammatory markers, sometimes Rosving’s sign positive (pain in the right iliac fossa on palpation of the left iliac fossa) |

|

|

Ascending colon diverticulitis |

Constant right-sided abdominal pain, sometimes with a preceding history of constipation |

| Left-sided pain | |

|

Descending/sigmoid colon diverticulitis |

Constant left-sided abdominal pain, sometimes with a preceding history of constipation |

Investigations

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations include:

- Basic observations (vital signs): mild tachycardia is common due to pain. For patients with a suspected infected system, look for signs of sepsis. This includes spiking fevers, hypotension and tachycardia.

- Urine dipstick: microscopic haematuria is common

- Urine microscopy, cultures and sensitivities (MC&S): to check for infection. However, a negative dipstick/MC&S for infection does not exclude an infected obstructed system, as in a completely obstructed ureter, urine cannot drain into the bladder.

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:

- Full blood count (FBC): neutrophilia can occur in renal colic, in isolation, it is not enough evidence of a superimposed infection

- Urea and electrolytes (U&Es): a reduction in renal function may indicate the need for intervention in colic patients

- C-reactive protein (CRP): if CRP is raised, this suggests a developing infection

- Lactate: if raised, can be a sign of worsening sepsis

Imaging

Relevant imaging investigations include:

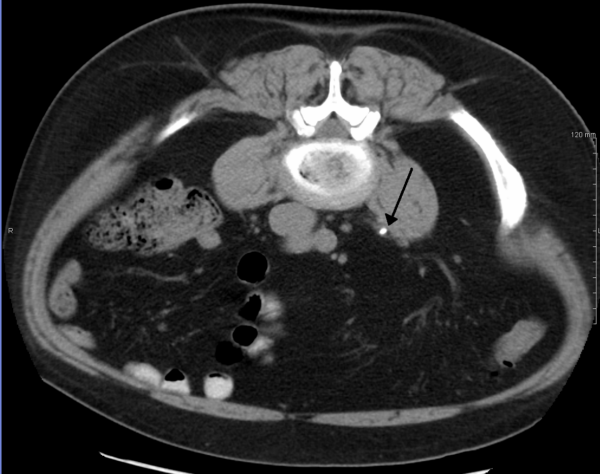

- Computed tomography of the kidneys, ureters and bladder (CT KUB): CT KUB is the gold-standard first-line investigation for renal colic and has a 97% specificity2. The British Association of Urological Surgery (BAUS) recommend a CTKUB within 14 hours of admission2. CTKUB has the added benefit of being able to measure stone density (in Hounsfield units) and demonstrate renal anatomy, which can affect management.

- Ultrasound: in young or pregnant patients, ultrasound can be used instead of CT. Ultrasound is not accurate in picking up small stones, although can be useful for demonstrating hydronephrosis and any additional signs of infection.

- X-Ray: for patients with known radio-opaque stones on previous imaging, an X-ray may demonstrate whether the stone has moved or been expelled. However, X-ray does not show the presence of hydronephrosis or radiological signs of infection.

Management

Conservative management

Short-term treatment of patients can involve conservative management (e.g. fluids). In the case of small stones (<5mm), a trial of waiting can be used. This involves waiting to see if the stone passes on its own.

This has the benefit of avoiding intervention but can be painful for patients. Adequate analgesia should be prescribed for these situations. Patients should be re-reviewed in an outpatient setting in approximately four weeks to ensure that the stone has passed. If the stone hasn’t passed, interventions should be considered.

Medical management

Medical management involves medical expulsive therapy and analgesia.

For analgesia, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) form the mainstay of treatment (e.g. diclofenac suppositories). There is very little role for opioid-based analgesia (e.g. codeine/morphine) in renal colic.

The use of medical expulsive therapy is controversial, and it doesn’t currently form part of the recommended European treatment algorithm.3 Despite this, some UK centres still use an alpha-adrenoceptor blocker (e.g. tamsulosin) for small distal ureteric stones.

Surgical management

Interventional management in the short term is reserved for patients that fit one of the following criteria:

- Irretractable pain despite good analgesia

- Acute kidney injury (AKI)

- Infected-obstructed kidney (urgent)

- Bilateral obstructed kidneys/obstructed kidney in a patient who has a single functioning kidney (emergency)

For patients with an infected urinary system, the most important management is relieving the obstruction. This can be done through either the insertion of a stent or a nephrostomy.

A stent is a small tube which sits in the ureter and allows the passage of urine from the kidney into the bladder. It is inserted under general anaesthetic with the help of a rigid camera through the urethra and into the bladder.

A nephrostomy is a tube placed percutaneously (through the skin) straight into the kidney. This has the benefit of not requiring a general anaesthetic but can be associated with complications, such as bleeding. These patients will still need treatment of their stones at a later date, with a ureteroscopy (camera up the ureter) and laser fragmentation of their stones.

For patients who do not have an infected system, primary stone treatment can be offered in the first instance. This can be done through either ureteroscopy and laser stone fragmentation or extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL).

ESWL is performed while patients are awake, whereby a series of shockwaves are focused onto the area of stone burden to break them down and allow passage. In hospitals where these are not available in the urgent setting, patients can once again be given a ureteric stent and brought back for treatment on an elective basis.

Advice for patients to prevent further stone formation

All patients should be advised to maintain a good fluid intake of at least 2-3 litres per day.

Specific dietary advice depends on the chemical composition of the stone:

- Calcium-based stones: 80% of renal calculi contain calcium-calcium oxalate (35%), calcium phosphate (10%), or mixed oxalate and phosphate (35%). Lemon juice can increase urinary citrate, reducing the recurrence of these.

- Oxalate stones: avoidance of oxalate-rich foods can reduce the risk of forming these stones (e.g. leafy greens, soy products and potatoes)

- Urate stones: avoidance of foods high rich in purines can reduce the risk of forming these stones (e.g. red meat, eggs and shellfish)

Complications

Complications of renal colic relate to obstruction of the ureter and the resulting hydronephrosis. These patients may present with an acute kidney injury (AKI), which will only resolve once the obstruction has been relieved.

In the case of an obstructed kidney, there can be a superimposed infection. This represents an urgent situation whereby patients can become septic if the obstruction is not treated promptly.

In the rare case of bilateral obstructing stones or an obstructing stone in a single kidney, emergency intervention is required to prevent rapid, life-threatening deterioration in these patients.

Key points

- Renal colic describes intense wave-like loin-to-groin pain related to the passage of ureteric stones.

- A combination of both patient and environmental risk factors can predispose to renal calculi formation.

- Typical symptoms include sudden onset, severe, loin-to-groin pain with nausea. The abdominal examination is usually normal.

- A ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm is an important differential diagnosis to consider, especially in older patients with vascular risk factors.

- Patients can be treated conservatively if they have small stones. Medical expulsive therapy is controversial but still used in many centres in the UK.

- Ureteric stents and nephrostomies can be used to relieve an obstructed urinary system. Bilateral obstruction or obstruction of a patient with a single kidney are both urological emergencies.

- Complications of renal colic relate to obstruction of the ureter and the resulting hydronephrosis (e.g. acute kidney injury).

Reviewer

Miss Amelia Pietropaolo

Associate Specialist in Urology

University Hospital Southampton

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

Text references

- Department for Work and Pensions. Occupational risks for urolithiasis: IIAC information note. Independent report. Published 2018. Available from: [LINK].

- Tsiotras A, Smith RD, Pearce I, O’Flynn K, Wiseman O. British Association of Urological Surgeons standards for the management of acute ureteric colic. J Clin Urol. 2018;11(1).

- Türk C, Neisius A, Petrik A, Seitz C, Skolarikos A, Thomas K. EAU Guidelines on Urolithiasis. Eur Assoc Urol 2018. 2018:1-87.

Image references

- Figure 1. James Heilman, MD. 3mm stone. License: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 2. Kristoffer Lindskov Hansen, Michael Bachmann Nielsen and Caroline Ewertsen. Renal ultrasonograph of a stone located at the pyeloureteric junction with accompanying hydronephrosis. License: [CC BY]

- Figure 3. Bill Rhodes. Kidney stones abdominal X-ray. License: [CC BY]