- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Haematuria is the presence of blood in the urine, either visible (seen by the naked eye) or non-visible (confirmed by urine dipstick or urine microscopy; 3+ red blood cells (RBCs) per high-powered field). Old textbooks use the phrase ‘frank haematuria’ or ‘microscopic and macroscopic haematuria’- these terms are now outdated.

The prevalence of microscopic haematuria in the adult population ranges from 2.4% to 31.1%.1

Aetiology

The cause of haematuria can range from benign to malignant. The probability of cancer must always be weighed up in a patient to consider further investigations.

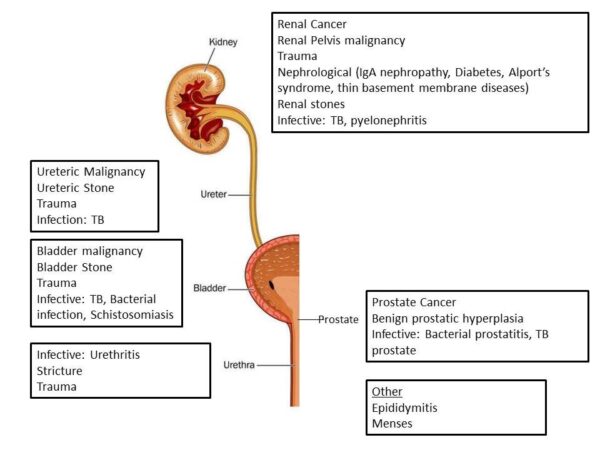

It may be useful to think of the causes of haematuria categorised by the anatomy of the urinary tract, from the kidneys to the urethra (Figure 1).

Risk factors

Approximately 13.8% of patients presenting with visible haematuria and 3.1% of patients presenting with non-visible haematuria are found to have an underlying urothelial malignancy.3

Risk factors for a urothelial malignancy include:4

- >60 years old

- Smoking history

- Occupational exposure (e.g. paints, dyes, metals or petroleum products in the workplace)

- Recurrent urinary tract infections

- Family history of bladder cancer

- Schistosomiasis among endemic countries

Clinical features

The presentation of haematuria can range from incidental detection on a urine dipstick test to overt visible haematuria. Initially, a thorough history and examination are necessary.

History

Key points in the history of a patient with haematuria include:

- Amount of blood

- Colour of urine/blood

- Relationship of blood to stream (i.e. beginning vs. end of stream)

- Presence of clots

- Urinary/ clot retention

Other important areas to cover in the history include:

- Flank pain: may suggest renal colic

- Fevers: evidence of infection

- Prostate symptoms (e.g. hesitancy, poor urinary stream, terminal dribbling): a large, vascular prostate could be the cause of the haematuria

- Medication history: patients with severe haematuria may benefit from withholding antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy

- Family history: kidney, bladder or prostate cancer

- Social history: smoking and industrial carcinogens (e.g. rubber, paints or dyes) put patients at increased risk of malignancy (particularly bladder cancer)

- Recent travel: if considering schistosomiasis

Clinical examination

In the context of haematuria, an abdominal examination should be performed to assess for tenderness or masses in the flanks (e.g. renal cancer) or suprapubic region (e.g. urinary retention).

A digital rectal examination may also be performed in males to assess for enlargement (e.g. prostate cancer) or tenderness (e.g. prostatitis) of the prostate.

Investigations

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations in the context of haematuria, include:

- Urine dipstick: this is especially useful if you suspect non-visible haematuria, for example in the diagnosis of renal colic or urinary tract infection (UTI). A urine dip can also identify proteinuria which may indicate a nephrological cause.

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations in the context of haematuria, include:

- Bloods (FBC, U&Es, coagulation, CRP): white cells may be raised in renal colic. It is also essential to establish baseline renal function.

- Group and save/cross-match: important if the patient has visible haematuria, particularly if they are haemodynamically unstable

- Midstream urine (MSU) test: bacteriuria

Imaging

All patients who present with haematuria require investigation of their upper and lower urinary tract. The upper urinary tract is investigated using radiological imaging, whilst the lower urinary tract can be investigated using flexible cystoscopy.

CT urogram with contrast

A first image is taken without contrast (equivalent to a CTKUB; this is the gold standard investigation for urinary tract stones).

Then, a second image is taken when the contrast is passing through the kidneys, this can help identify causes for haematuria in the upper urinary tract (e.g. renal tumour).

Finally, a third image is taken after 15 to 20mins when the contrast is in the urine (urographic phase) which can identify filling defects in the kidney, ureter or bladder that may be caused by a urothelial tumour.

Urinary tract U/S

This is a safe procedure with no radiation exposure that can identify most urinary tract pathology.

However, urinary tract ultrasound is not as accurate as a CT urogram so when patients are at high risk of malignancy,(e.g. visible haematuria or heavy smokers) a CT urogram is preferred.

Flexible cystoscopy

Flexible cystoscopy involves the insertion of a thin flexible camera into the urethra and bladder.

Flexible cystoscopy allows direct visualisation of the tissues of the lower urinary tract, allowing the operator to identify causes of haematuria (e.g. bladder cancer, bladder stones, prostatic bleeding or urethral strictures).

Management

Overall management of haematuria depends on the underlying pathology.

Referral pathway for haematuria

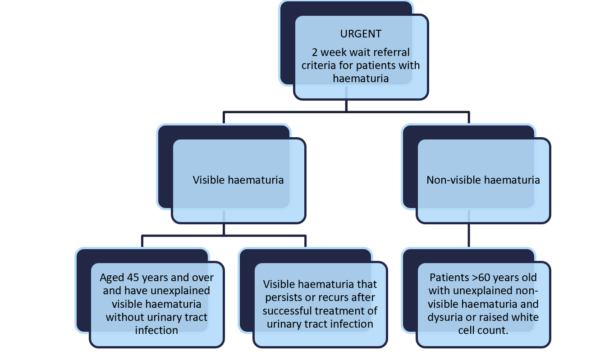

Urgent referral should be considered for any patient with suspected urinary tract malignancy,

Patients who present to their GP with haematuria and certain criteria will undergo urgent outpatient tests and investigations under the 2-week wait pathway (Figure 2).5 Investigations may include a CT urogram or USS (this would be a clinical decision based upon their age and degree of haematuria) and flexible cystoscopy.

Emergency management of haematuria

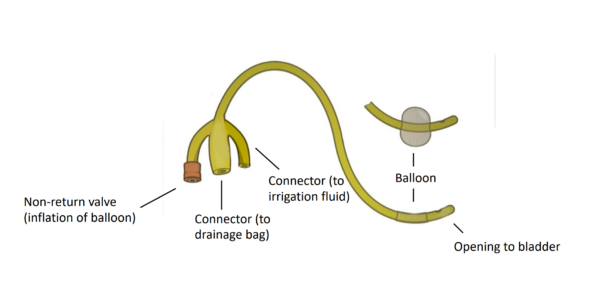

Some patients may present with heavy haematuria or clot retention and require a 3-way catheter. A 3-way catheter has three lumens, which are larger than other catheters. One lumen allows for inflation of the catheter balloon, one is for irrigation/washouts, and one attaches to the catheter bag (Figure 3).

After catheterisation, it is important to perform a bladder washout until the urine runs clear. Washouts are done to break down and remove clots from the bladder – it is important to continue the washouts until all the clots are removed.

After washout, continuous bladder irrigation is set up to prevent further clots from forming.

Overall, patients requiring a 3-way catheter with washouts will need to be admitted to the urology ward for further review.

Key points

- Haematuria can be visible or non-visible and benign or malignant.

- Risk factors for urinary tract cancer include age >60, smoking, industrial exposure, recurrent urinary tract infections and a family history of bladder cancer.

- Primary investigations for haematuria include blood tests, urinalysis and midstream urine sample for culture.

- Other investigations essential for diagnosis include upper tract imaging and flexible cystoscopy.

- Urgent referral (2-week) should be performed for any patients with suspected malignancy.

References

- Davis R, Jones JS, Barocas DA, et al. Diagnosis, evaluation and follow-up of asymptomatic microhematuria (AMH) in adults: AUA guideline. Published in 2012. Available from: [LINK]

- Pixy.org. Urinary Tract Infection. Published in 2015 (adapted by author). License: [CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0].

- Tan W, Feber A, Sarpong R et al. Who Should be investigated for Haematuria? Results of a Contemporary Prospective Observational Study. Published in 2008. Available from: [LINK]

- Vladanov I, Pleșacov A, Colța A. Bladder cancer risk factors and prevention. Published in 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- NICE Guidelines. Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. Published in 2015. Available from: [LINK]

- Olek Remesz. Foley catheter inflated and deflated EN. Published in 2011. License: [CC-BY-SA 3.0]. (Adapted by authors)

Reviewer

Mr James Brewin

Consultant Urologist