- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukaemia is a malignant neoplastic disease affecting white blood cells. Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) is also called acute myelogenous or myelocytic leukaemia.

AML is responsible for about 25% of childhood leukaemias, often developing in infancy. However, the incidence of AML increases with age. It is the most common acute leukaemia in adults, with a median age of onset of 68 years.1

Aetiology

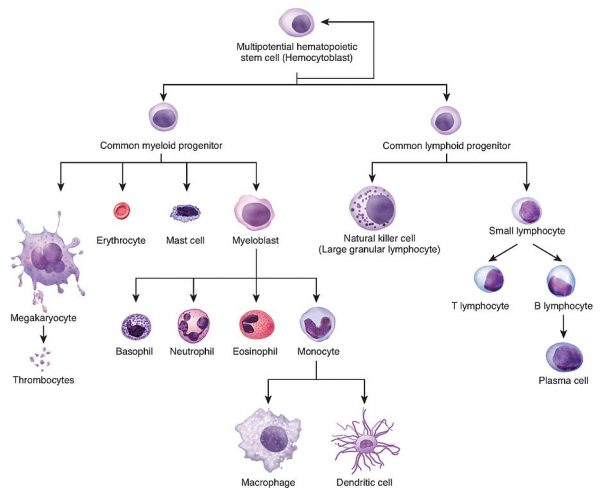

AML arises from the uncontrolled growth of the myeloid cell line in the bone marrow (Figure 1).

This uncontrolled growth leads to a proliferation of immature, non-functional white blood cells, known as “blasts”. These blasts disrupt normal haematopoiesis, which is the formation of blood cell components.

When normal haematopoiesis is impaired this can cause pancytopenia, where there is a reduction in the number of red and white blood cells, as well as platelets.

Low red blood cells (RBC) leads to symptoms and signs of anaemia. Low platelets (thrombocytopaenia) manifest as bleeding and bruising. Low white cells (WCC) lead to an increased susceptibility to infection.

Immature blast cells may enter the bloodstream and infiltrate other organs such as the central nervous system, liver, and skin.

Risk factors

The most common risk factor for AML is myelodysplastic syndrome and other pre-existing haematological disorders.

However, in the majority of cases, AML appears as a de novo malignancy in previously healthy individuals.

The following risk factors are associated with AML:1,3

- Pre-existing haematological disorders: myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), myeloproliferative disorders (MPD), aplastic anaemia, paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria (PNH)

- Congenital disorders: Down’s syndrome, Bloom syndrome

- Environmental exposure: prior chemotherapy, radiation, tobacco smoke, benzene

- No identifiable cause: genetic alterations, isolated gene mutations

Clinical features

History

Some patients with AML will be asymptomatic and present with only laboratory abnormalities.

Symptoms of acute myeloid leukaemia may be present for only days to weeks before diagnosis.

The most common presenting symptoms are due to disrupted hematopoiesis. These symptoms include:

- Anaemia: fatigue, weakness, pallor, malaise, palpitations, dyspnoea, tachycardia, and exertional chest pain

- Thrombocytopaenia: mucosal bleeding, easy bruising, petechiae/purpura, epistaxis, bleeding gums, and heavy menstrual bleeding. Occasionally, patients can present with spontaneous haemorrhage, including intracranial or intra-abdominal haematomas.

- Neutropaenia: increased susceptibility to infections. Patients may present with fevers in the presence of a severe and/or recurrent infection. Patients often have a history of upper respiratory infection symptoms that have not improved despite treatment with antibiotics.

- Leukaemic infiltration: abdominal discomfort/fullness may be present due to hepatosplenomegaly.

Other important areas to cover in history include:

- Past medical history: pre-existing haematological disorders, autoimmune disorders, medication history

- Predisposing risk factors: prior chemotherapy, radiation, tobacco smoke, benzene

Clinical examination

The clinical presentation of AML can vary greatly.

Typical clinical findings in AML may include:

- Weight loss

- Physical signs of anaemia, including pallor and a cardiac flow murmur

- Fever and other signs of infection such as lung findings consistent with pneumonia

- Thrombocytopaenia can cause petechia, dermal bleeding and ecchymoses

- Leukaemic infiltration of the organs can result in hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and swollen gums

Less common findings, which usually appear in later stages, include:

- Leukaemia cutis refers to the infiltration of the skin with leukaemia cells

- Respiratory distress and altered mental status are clinical signs that may indicate leukostasis. This is a medical emergency, which is characterised by an extremely elevated blast cell count.

Differential diagnoses

Pancytopenia can be caused by a variety of diseases with a wide range of severities. It is important to distinguish a patient with AML from a patient with another haematological disorder.

Table 1. The differential diagnoses of leukaemia.

| Haematological | Infections | Autoimmune diseases | Other |

|

Aplastic anaemia Myelodysplastic syndrome Myelofibrosis Lymphoma Lymphoproliferative disorders Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria |

Epstein-Barr virus Cytomegalovirus HIV Parvovirus B19 |

Systemic lupus erythematous

|

Cytotoxic therapies Radiation Drug-induced (e.g. methotrexate) |

Investigations

The diagnostic workup of AML involves the integration of history, clinical presentation, and laboratory results.

A diagnosis of AML is made by either identifying ≥20% myeloid blasts in the bone marrow (or peripheral blood) or detecting specific cytogenetic abnormalities.

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:

- Full blood count: white cell count may be normal, elevated, or low. Red blood cells may be low, revealing anaemia which is usually normocytic/normochromic. The platelet count may be low (thrombocytopaenia).

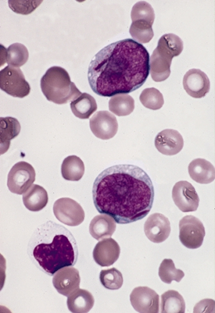

- Peripheral blood smear: may show myeloblasts which are immature cells with large nuclei, usually with prominent nucleoli. Auer rods may also be seen (Figure 2). These are pathognomonic of myeloblasts and they vary in frequency depending upon the AML subtype. They can be identified as pink/red rod-like granular structures in the cytoplasm. These are myeloperoxidase positive.

- Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH): may be elevated due to increased cell turnover

- Uric acid: may be elevated due to increased cell turnover

- Coagulation profile: may be deranged or show disseminated intravascular coagulation

Bone marrow biopsy

A bone marrow biopsy is required to stage the disease. The percentage of blasts determines chronic vs accelerated vs blast crisis.

Typically, both bone marrow aspiration and bone marrow trephine biopsy are performed. An aspirate is when a syringe of liquid bone marrow is filled while a trephine is when a 1-2cm piece of core bone marrow is removed in one piece.

In AML, the bone marrow is usually hypercellular because the normal cellular components are partially or totally replaced by immature or undifferentiated cells.

Analysis that is typically performed on the bone marrow includes:

- Immunophenotyping by flow cytometry

- Cytogenetics: a study of chromosomal structure, location, and function in cells

- Fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH): a laboratory technique for detecting and locating a specific DNA sequence on a chromosome

- Molecular analyses: molecular genetic techniques involve a combination of procedures to isolate and analyse the DNA or RNA transcribed from a particular gene

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry may be performed with peripheral blood or marrow aspirate.

It is used to identify circulating myeloblasts by characteristic patterns of surface antigen expression. The patterns of surface antigen expression vary amongst AML subtypes, but the majority express CD34, HLA-DR, CD117, CD13, and CD33.4,5,6,7

Classification

AML is classified using either the World Health Organization (WHO) classification or the French-American- British (FAB) classification.

World Health Organization (WHO) 2016 classification

The World Health Organization (WHO) classification system is based upon a combination of morphological, immunophenotypical, genetic, and clinical features:9,10

- AML with recurrent genetic abnormalities

- AML with myelodysplasia (MDS)-related changes

- Therapy-related myeloid neoplasms

- AML, not otherwise specified

- Myeloid sarcoma

- Myeloid proliferations related to Down’s syndrome

French-American-British (FAB) classification

The FAB classification of AML is based on the type of cell from which the leukaemia developed and its degree of maturity.4

- M0: acute myeloblastic leukaemia without maturation

- M1: acute myeloblastic leukaemia with minimal granulocyte maturation

- M2: acute myeloblastic leukaemia with granulocyte maturation

- M3: acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APL)

- M4: acute myelomonocytic leukaemia

- M5: acute monocytic leukaemia

- M6: acute erythroid leukaemia

- M7: acute megakaryoblastic leukaemia

The WHO classification is more clinically useful and produces more meaningful prognostic information than the FAB criteria.

Management

Chemotherapy

The mainstay of treatment in AML is chemotherapy. Chemotherapy regimes in AML consist of an induction period, consolidation period, and maintenance therapy.11

Induction

Induction chemotherapy is a shorter and more intensive period of treatment that can last from 2-6 weeks.

The goal is to clear the blood of leukemic cells (blasts) and to reduce the number of blasts in the bone marrow to a normal level. This is high-dose chemotherapy that can cause severe side-effects.

Consolidation

Consolidation chemotherapy is given once a patient has recovered from the induction phase.

The aim of consolidation is to kill the remaining blast cells. It is indicated even if there is no evidence of tumour cells remaining after induction.

Consolidation is usually given in cycles and the dosage of chemotherapy is usually lower. Although it is a lower dose, it is still significant and can cause severe side-effects.

Maintenance

Maintenance chemotherapy involves administering a low dose of chemotherapy regularly to maintain remission. This period can last from months up to 2 years.

The most common chemotherapeutic agents used in AML include:

- Cytarabine (cytosine arabinoside – ara-C): this is classified as an anti-metabolite12

- Daunorubicin (daunomycin) or idarubicin: this is classified as an anthracycline13

- All-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) and arsenic are more commonly used in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APML)

Bone marrow transplantation

A bone marrow transplant is also called a stem cell transplant or, more specifically, a hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

For AML these are usually allogenic transplants where stem cells come from another person, called a donor. The donor’s stem cells are given to the patient after the patient has chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy.

Bone marrow transplant is usually indicated in patients with:14

- High cytogenetic risks

- Lack of complete remission after first induction treatment

- High initial leukocyte count

Supportive therapy

Supportive therapies for AML include:15,16,17,18

- Blood cell transfusions: platelet transfusions are performed when platelets fall below < 10 × 109/L. Red cell transfusions are performed when haemoglobin is < 7 or 8 g/dL.

- Adequate analgesia and good oral hygiene are essential in the management of mucositis. Oral hygiene agents include Mycostatin and chlorhexidine mouthwash. Parenteral feeding may be considered in patients undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation.

- Antimicrobial prophylaxis: there is an increased risk of developing bacterial, fungal, and viral infections in neutropenic patients. Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) prophylaxis with co-trimoxazole is used in certain patients. An anti-viral such as valacyclovir is considered in some patients to prevent re-activation of herpes simplex virus (HSV). Antifungals are also considered. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are used for febrile patients or when an infection is suspected.

- Allopurinol: to prevent the build-up of uric acid caused by tumour lysis.

- Anti-emetics: used in the prophylaxis and treatment of nausea and vomiting.

Complications

AML may be associated with life-threatening complications.

Certain subclassifications of AML have been associated with specific complications (e.g. disseminated intravascular coagulation – DIC) in acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APML). 7,19

Complications of AML include:

- Leukostasis (extremely elevated blast cell count): causing respiratory and/or neurologic distress in a patient with AML

- Tumour lysis syndrome: when cancer cells break down quickly in the body, levels of uric acid, potassium, and phosphorus rise faster than the kidneys can remove them

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation: when proteins that control blood clotting become overactive. This can cause blood clots in small vessels and hypo-perfusion of organs. It can also cause clotting proteins to be consumed, leading to an elevated risk of serious bleeding.

Prognosis

Age is the most significant patient-specific risk factor in acute myeloid leukaemia. For those >60 years old, the prognosis is improving but remains poor.20

The 5-year survival rate for people 20 and older with AML is approximately 25%. For people younger than 20, the survival rate is 67%.21

Key points

- Acute myeloid leukaemia is a cancer of white blood cells that arises from the uncontrolled growth of the myeloid cell line in the bone marrow.

- AML is responsible for about 25% of childhood leukaemia, but it is the most common acute leukaemia in adults.

- The most common risk factor for AML is myelodysplastic syndrome and other pre-existing haematological disorders.

- Some patients may be asymptomatic with AML while others present with signs and symptoms of anaemia, thrombocytopaenia, neutropenia and leukaemic infiltration.

- A diagnosis of AML requires identifying ≥20% myeloid blasts in the bone marrow (or peripheral blood).

- Full blood count, LDH, uric acid and peripheral blood smear are the primary investigations. These may be followed by a bone marrow aspirate and biopsy.

- The mainstay of treatment in AML is chemotherapy. This regime usually consists of an induction period, consolidation period and maintenance therapy.

- Serious complications of AML include leukostasis, tumour lysis syndrome, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Reviewer

Dr Kevin Maxwell

Haematology registrar

Cork University Hospital

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- De Kouchkovsky I, Abdul-Hay M. Acute myeloid leukemia: a comprehensive review and 2016 update. Blood Cancer J. 2016;6(7):e441.

- OpenStax. Haematopoiesis. Licence: [CC-BY]. Available from: [LINK]

- Vakiti, A.; Mewawalla, P.; Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2020, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2020 Nov 21.

- Angelescu, S.; Berbec, NM.; Colita, A.; Barbu, D.; Lupu, AR.; Value of multifaced approach diagnosis and classification of acute leukemias. Maedica (Bucur) 2012;7(3):254-60.

- Jonathon, E.; Kolitz, M.; Overview of acute myeloid leukemia in adults 2020 [Topic 94786 Version 5.0]. Available from: [LINK].

- Younes S. Acute leukaemia PathologyOutlines.com website. Available from: [LINK].

- Percival, ME.; Lai, C.; Estey, E.; Hourigan, CS.; Bone marrow evaluation for diagnosis and monitoring of acute myeloid leukemia Blood Rev. 2017;31(4):185-92.

- The Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP). Two myeloblasts with single, prominent auer rods. Licence: [Public domain]. Available from: [LINK]

- Arber, DA.; Orazi, A.; Hasserjian, R.; Thiele, J.; Borowitz, MJ.; Le Beau, MM.; et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. 2016;127(20):2391-405.

- Sabattini, E.; Bacci, F.; Sagramoso, C.; Pileri, SA.; “WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues in 2008: an overview” 2010;102(3):83-7.

- Society, AC.; Treating Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML). August 21, 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- Magina, KN.; Pregartner, G.; Zebisch, A.; Wölfler, A.; Neumeister, P.; Greinix, HT.; et al. Cytarabine dose in the consolidation treatment of AML: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 130. United States2017. p. 946-8.

- Murphy, T.; Yee, KWL.; Cytarabine and daunorubicin for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2017;18(16):1765-80.

- Müller, LP.; Müller-Tidow, C.; The indications for allogeneic stem cell transplantation in myeloid malignancies. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112(15):262-70.

- Ashkan, Emadi.; Law, JY.; Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML)(Acute Myelocytic Leukemia; Acute Myelogenous Leukemia). MDS Manual Professional Version. May 2020. Availible from: [LINK]

- Hong, CHL.; Gueiros, LA.; Fulton, JS.; Cheng, KKF.; Kandwal, A.; Galiti, D.; et al. Systematic review of basic oral care for the management of oral mucositis in cancer patients and clinical practice guidelines. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(10):3949-67.

- Rajesh V, Lalla.; Stephen T, Sonis.; Douglas E, Peterson.; Management of Oral Mucositis in Patients with Cancer. Dental Clinics of North America. January 2008. p. 61-77.

- Krakoff, IH.; Use of allopurinol in preventing hyperuricemia in leukemia and lymphoma. 1966;19(11):1489-96.

- Rose-Inman, H.; Kuehl, D.; Acute leukemia. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2014;32(3):579-96.

- Döhner H., Weisdorf D.J., Bloomfield C.D. Acute myeloid leukemia. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373:1136–1152.

- Liersch, R.; Müller‐Tidow, C.; Berdel E.; Krug U. Prognostic factors for acute myeloid leukaemia in adults – biological significance and clinical use. British Journal of Haematology. Volume165, Issue1. April 2014. Pages 17-38. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.12750