- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

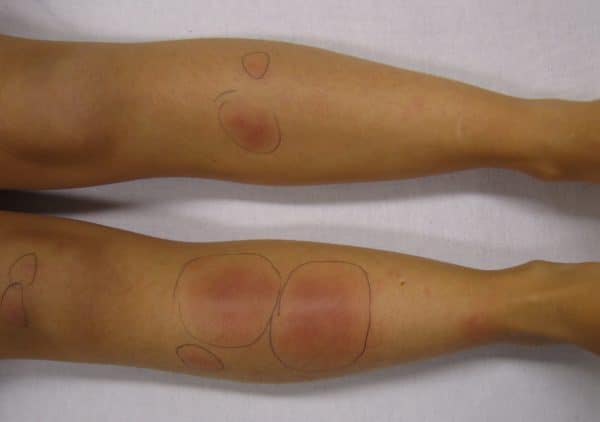

Erythema nodosum (EN) is a painful, inflammatory condition characterised by inflammation of subcutaneous fat (panniculitis). It commonly presents as tender, erythematous nodules and plaques on the anterior shins.

EN is six times more common in women and typically affects those aged between 25-40.

Erythema nodosum occurs in approximately one to five per 100,000 persons.1,2

Aetiology

Erythema nodosum is thought to be a hypersensitivity reaction of unknown cause. It can be triggered by several different stimuli or systemic conditions (Table 1).2

Approximately 50% of cases are classified as idiopathic.4

Table 1. Possible triggers of erythema nodosum (most common triggers highlighted in bold).1,2,3,5

| Category | Triggers |

|

Idiopathic |

|

|

Infections |

|

|

Inflammatory |

|

|

Drugs |

|

|

Malignancies |

|

|

Other |

|

Histopathology

Panniculitis is differentiated depending on the area of maximal microscopic inflammation on biopsy and is classified as predominantly septal (inflammation around connective tissue septa) or lobular (inflammation of fat lobules) with or without vasculitis.

Erythema nodosum is the most common form of panniculitis and is classified as a septal panniculitis without vasculitis.3

Other types of septal panniculitis include necrobiosis lipoidica and lipodermatosclerosis. Nodular vasculitis is an example of a lobular panniculitis with vasculitis.3

Clinical features

Prodrome

A prodrome of arthralgia, commonly of the ankles and knees, malaise and fever may occur one to three weeks before the onset of the classical rash.4,6,7

Rash

Erythema nodosum classically presents as tender, warm, erythematous subcutaneous nodules and plaques. These lesions are often poorly defined and can be up to 20cm in diameter.3,7

The distribution of lesions typically involves the anterior aspect of the lower legs, however, lesions can occur anywhere. The nodules and plaques tend to be symmetrical and bilateral.

Initially, the subcutaneous nodules are firm but later develop into more fluctuant lesions.

The lesions tend to be bright to deep red and then typically fade to dusky blue/purple then yellow, resembling a resolving bruise.3 However, lesions are sometimes better palpated than visualised.1,7

Ankle swelling, alongside arthralgia, is often associated with erythema nodosum.3

Differential diagnoses

Differential diagnoses to consider in the context of erythema nodosum include:

- Trauma

- Cellulitis and erysipelas

- Other types of panniculitis including nodular vasculitis and lipodermatosclerosis

Investigations

Erythema nodosum is usually a clinical diagnosis.3

It is important to investigate potential underlying causes and conditions. Due to the vast number of underlying causes, a thorough and detailed history and examination must be performed to guide the investigation strategy.

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations include:

- Urine pregnancy test (human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) urine dipstick)

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:

- Baseline blood tests (FBC, CRP, ESR): inflammatory markers are likely to be raised in EN

- Throat swab for microscopy, culture & sensitivity and anti-streptolysin-O titre (ASOT): swab is positive for streptococcus in current streptococcal infection and ASOT is elevated in recent streptococcal infection

- Tuberculin skin test or interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA): positive in tuberculosis

Imaging

Relevant imaging investigations include:

- Chest X-ray: hilar lymphadenopathy may indicate sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, mycoplasma or lymphoma

Additional investigations

Additional investigations to consider may include:

- Serum ACE and calcium: elevated in sarcoidosis

- Viral titres and serology: to assess for herpes simplex virus, Epstein-Barr virus, hepatitis B and C virus and HIV

- Stool culture, including ova and parasites (if diarrhoeal symptoms present): to assess for gastrointestinal infection

- Colonoscopy (if gastrointestinal symptoms present): to assess for inflammatory bowel disease

- Excisional skin biopsy: if the clinical diagnosis is in doubt, a biopsy is particularly useful in differentiating between predominantly septal or lobular panniculitis.1,3,7

Management

Erythema nodosum is usually self-limiting and treatment should be aimed at managing the underlying condition and providing supportive therapies.5,7

Supportive management may include:1

- Bed rest

- Elevation and compression of affected limbs

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): useful for skin nodule and joint pain

- Stop any causative drugs

- Treatment of any underlying cause

- Short-term oral potassium iodide may be useful in particularly problematic cases, however, prolonged use should be avoided due to the risk of hyperthyroidism

Complications

Erythema nodosum usually resolves within six weeks, without scarring.6 However, arthralgia related to the prodrome period can continue for up to two years.2,7

Key points

- Erythema nodosum is the most common type of panniculitis and is thought to be a hypersensitivity reaction of unknown cause.

- EN is commonly idiopathic in nature but can be associated with several systemic diseases and conditions.

- Tender, erythematous subcutaneous nodules are a defining feature of erythema nodosum.

- Erythema nodosum is typically self-limiting. However, if an associated systemic disease is identified, management should be targeted at treating the associated systemic disease.

Reviewer

Dr Tom King

Dermatology Consultant

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- R. Schwartz and S Nervi. Erythema nodosum: a sign of systemic disease. Published in 2007. Available from: [LINK].

- W. Hafsi and T.Badri. Erythema Nodosum. Published in 2021 Available from: [LINK].

- DermNet NZ. Erythema nodosum. Published in 2019. Available from: [LINK].

- J. Cowan and M. Graham. Evaluating the clinical significance of erythema nodosum. Published in 2005. Available from: [LINK].

- A. Leung, K. Leong and J. Lam. Erythema nodosum. Published in 2018. Available from: [LINK].

- M. Chowaniec, A. Starba and P. Wiland. Erythema nodosum – review of the literature. Published in 2016. Available from: [LINK].

- PCDS. Erythema nodosum. Published in 2021. Available from: [LINK].

- J. Heilman. Erythema nodosum on the lower limbs in a person who had recently had streptococcal pharyngitis. Licence [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK].

- Medicalpal. Erythema nodosum on the lower limbs in a person with darker skin tone. Licence [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK].

- Ganguly. Typical red nodule of erythema nodosum. Licence [CC BY]. Available from: [LINK].