- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

As a doctor working in a hospital setting, it is very common to be presented with blood test results showing abnormal electrolytes. These may be for patients you manage as part of a ward team or patients previously unknown to you during an on-call shift.

This article is not an exhaustive list of how to manage every electrolyte disturbance but aims to provide a quick reference guide and some hints and tips from clinical experience.

Each hospital will have specific guidelines for managing electrolyte disturbances, and this should be your ultimate reference guide when working at that site. Guidelines can vary slightly from site to site, although the underlying principles of managing electrolyte disturbance remain the same.

If there are multiple electrolyte disturbances in the same patient, always seek senior help for the best approach to replace electrolytes sequentially.

After the acute management of the electrolyte disturbance described here, it is important to consider and investigate the underlying cause of this disturbance. Severe electrolyte disturbances will require close monitoring throughout your on-call shift to ensure continued improvement.

Hypokalaemia

Hypokalaemia is defined as serum potassium <3.5mmol/L. Severe hypokalaemia can be defined as a serum potassium level <2.5mmol/L.

Hypokalaemia is of clinical significance as a low serum potassium can destabilise the myocardium. As such, the first important step is to request an ECG.

ECG features of hypokalaemia

ECG changes associated with hypokalaemia include PR prolongation, widespread ST depression / T wave flattening and prominent U waves.

Management

Management of hypokalaemia depends on serum potassium level, presence of symptoms (palpitations, muscle weakness, paraesthesia) and ECG changes:1

- If potassium is >3mmol/L, the patient is asymptomatic, and there are no ECG changes, oral potassium replacement can be given (e.g. dissolvable potassium supplements such as ‘Sando-K’, two tablets dissolved in water, 2-3 times daily).

- If potassium is <3mmol/L or ECG changes are present, intravenous potassium replacement is indicated. Consider cardiac monitoring, especially if ECG changes are present.

Follow trust guidelines for replacement regimens. Regardless of the oral agent used, ensure a dose is given immediately – do not wait until the following day to start replacement. The maximal rate of peripheral potassium replacement in a ward setting is usually 10mmol/hour.

Always recheck the potassium level after 4-6 hours of replacement in cases where IV potassium is warranted.

Hypomagnesaemia and hypokalaemia

Hypomagnesaemia often accompanies hypokalaemia.

Magnesium deficiency impairs potassium reabsorption in the renal tubules, exacerbating potassium losses. Hypomagnesaemia can hinder the effectiveness of potassium replacement. It is always worth checking magnesium levels in patients with hypokalaemia.

Hyperkalaemia

Hyperkalaemia is defined as serum potassium >5.5mmol/L. It can be further classified in terms of severity as per European Resuscitation Council guidelines:

- Mild: 5.5-5.9 mmol/L

- Moderate: 6.0-6.4 mmol/L

- Severe: >6.5 mmol/L

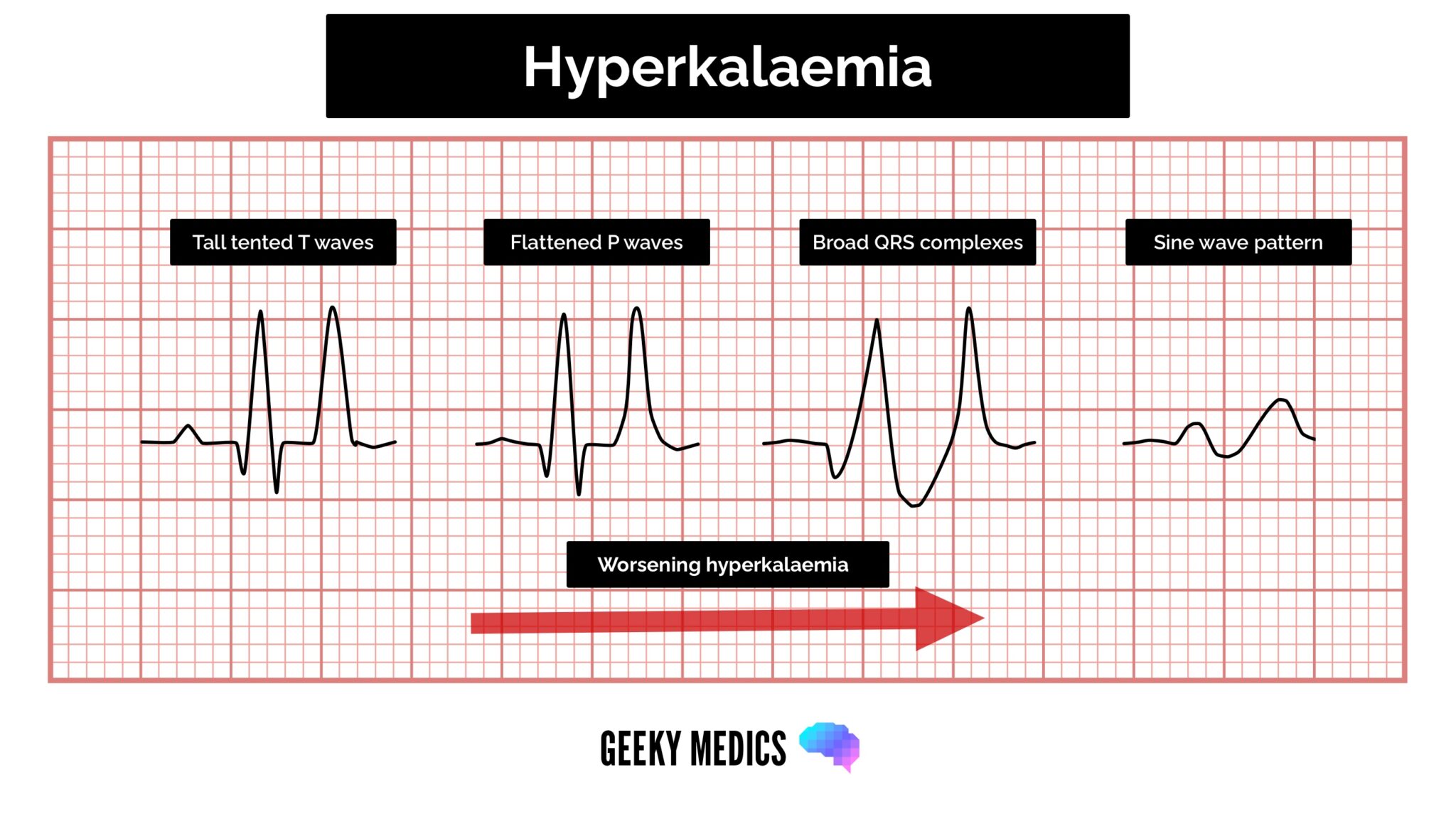

ECG features of hyperkalaemia

The cardinal features of hyperkalaemia on the ECG are peaked T waves, prolonged PR interval and widened QRS complexes.

Management

Mild or moderate hyperkalaemia

For mild or moderate hyperkalaemia, the key is to assess for the presence of ECG changes and whether the patient is well or symptomatic (palpitations, severe malaise/lethargy).

In a well patient without ECG changes, most hospital guidelines will recommend a thorough assessment to look for an underlying cause (e.g. AKI, rhabdomyolysis, medications) and appropriate treatment related to this cause (e.g. IV fluids in AKI). If unsure of the underlying cause, always discuss with a senior (particularly if potassium >6mmol/L).

Severe hyperkalaemia

Severe hyperkalaemia, or hyperkalaemia associated with symptoms or typical ECG changes, is a medical emergency. Patients must be placed on continuous cardiac monitoring, and immediate management is required:

- Stabilise the myocardium with IV calcium: this may be calcium chloride or calcium gluconate, according to hospital protocol; doses may need repeated up to three times until ECG changes resolve

- Shift potassium intracellularly: insulin/dextrose infusion +/- nebulised salbutamol

- Identify and treat underlying cause: AKI, drugs (e.g. ACEs, spironolactone), rhabdomyolysis

After initiating treatment for hyperkalaemia, the serum potassium needs to be closely monitored (initially hourly if severe) until it has normalised.

It is not uncommon for multiple rounds of treatment to be required to manage severe hyperkalaemia. Even if the potassium initially normalises, it is recommended to re-check this frequently throughout an on-call shift (within 4-6 hours), as potassium concentration can quickly rise after the initial treatment effect wears off.

If initial efforts at treatment are unsuccessful, escalate quickly to senior doctors, as this is a medical emergency. For a full understanding of hyperkalaemia, see our dedicated hyperkalaemia guide.

Hyponatraemia

Hyponatraemia is defined as a serum sodium level <135mmol/L.

Acute hyponatraemia can be life-threatening due to cerebral fluid shifts associated with the reduction in serum sodium. Hyponatremia is a complex topic, and treatment can vary according to the underlying cause and the patient’s fluid status.

The key to interpreting sodium levels during an on-call shift is understanding that the rate of change in sodium concentration is just as important as the absolute sodium level.

Severe hyponatremia can be defined as a serum sodium concentration <120mmol/L. However, a rapid fall in sodium from 145mmol/L to 125mmol/L over 24 hours can be of equal concern.

Management

Acute hyponatremia with associated symptoms (confusion, decreased GCS, seizures) is a medical emergency and requires early escalation to senior clinicians. These patients may require intensive care admission and hypertonic saline administration.3

High-level monitoring is required to avoid correcting hyponatraemia too rapidly, as this can lead to intracerebral fluid shifts with significant complications (central pontine myelinolysis).

Most cases of hyponatremia will be mild or moderate (>120mmol/L). In these cases, assess the rate of change in sodium concentration and the patient’s neurological status.

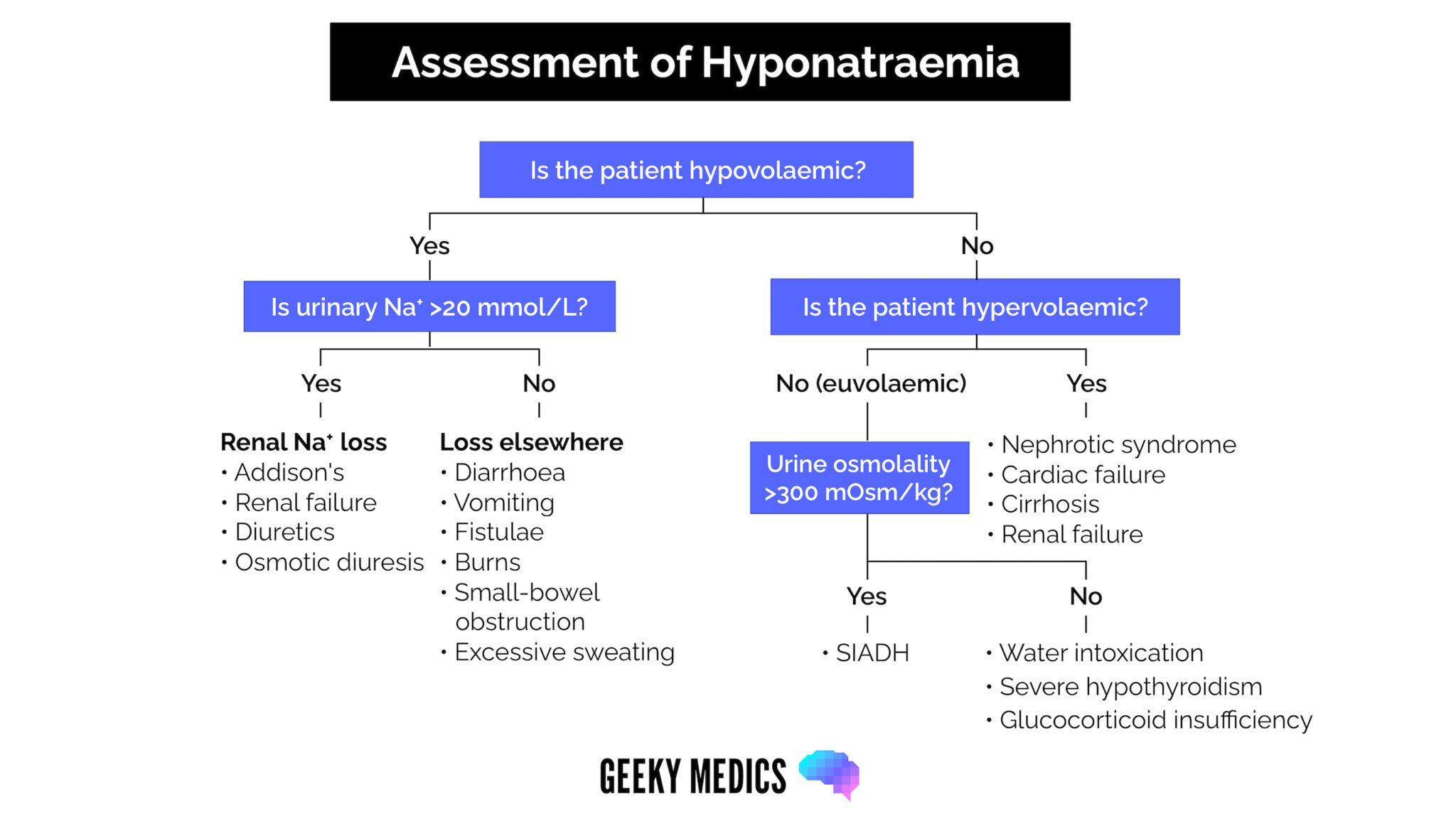

If the rate of change is not rapid and the patient is asymptomatic, ward-based management is likely appropriate. Perform a fluid status examination, and consider initiating treatment based likely on the underlying cause (e.g. increased diuresis if the patient is hypervolemic, gentle normal saline administration if the patient is hypovolemic, fluid restriction if the patient is euvolemic).

Paired urine/serum osmolality (+ urine sodium) is the first line investigation worth sending during an on-call shift, for review by the patient’s medical team.

Review the medication chart for common culprits of hyponatremia (e.g. thiazide diuretics) and consider withholding these for the medical team to review in the morning.

Have a low threshold to discuss these patients with your senior doctor, especially if the sodium is <125mmol/L, as the management can be complex.

In general, sodium levels should not be corrected at a rate >0.5mmol/L per hour or >10mmol in 24 hours. Always re-check the sodium level within a few hours of initiating treatment if sodium is <125mmol/L to ensure it is not correcting too quickly.

For more information on hyponatremia, including the initial assessment and early management based on fluid status examination – check out our dedicated hyponatraemia guide.

Hypernatraemia

Hypernatraemia is defined as a serum sodium level >146mmol/L. Severe hypernatraemia is a sodium level >160mmol/L.

Hypernatraemia is most commonly caused by dehydration (e.g. unreplaced skin or GI losses of hypotonic fluid).5

Management

If severe hypernatremia is present, this is a medical emergency and should be escalated immediately to senior doctors. These patients may need a high-dependency level bed for treatment and monitoring.

For patients with mild or moderate hypernatraemia, if there is a clear history implicating dehydration (e.g. vomiting/diarrhoea) and the patient looks clinically dehydrated, initial treatment involves gentle rehydration. Intravenous hypotonic fluids that do not contain sodium are the mainstay of treatment (e.g. 5% dextrose).

Calculating the fluid rate required based on total body water deficit is possible, but this should always be checked with a senior doctor.

Again, sodium levels should not be corrected at a rate >0.5mmol/L per hour or >10mmol in 24 hours. Correcting the hypernatraemia too rapidly can lead to intracerebral fluid shifts and devastating consequences such as central pontine myelinolysis (also known as osmotic demyelination syndrome).

Always recheck the sodium level within 2-4 hours of initiating treatment.

Hypocalcaemia

Hypocalcaemia is defined as serum calcium <2.2 mmol/L. Severe hypocalcaemia is generally defined as serum calcium <1.9 mmol/L.

Mild hypercalcemia is generally associated with mild symptoms such as lethargy and weakness. However, severe hypocalcaemia can cause serious symptoms such as tetany, laryngospasm/bronchospasm or seizures.

Hypocalcaemia is also known to adversely affect the myocardium, with the classical ECG finding being QT prolongation, which can progress to torsades de pointes and cardiac arrest.

Management

All patients with hypocalcaemia should be assessed for symptoms or ECG changes. Mild hypocalcaemia without symptoms or ECG changes can be treated with oral calcium replacement (e.g. calcium carbonate, 1500mg tablets, 1-2 times daily).5

IV calcium replacement is indicated if the hypocalcaemia is severe or associated with significant symptoms or ECG changes. This is most commonly given in the form of IV calcium gluconate, although check your individual hospital’s guidelines.

For more information on the causes and investigation of hypocalcaemia, see our dedicated guide to bone profile interpretation.

Hypercalcaemia

Hypercalcaemia is defined as serum calcium >2.6 mmol/L. Severe hypercalcaemia can be defined as serum calcium >3.5 mmol/L.

Symptoms are classically remembered as ‘bones (pain), stones (renal), abdominal groans (pancreatitis, constipation) and psychic groans (confusion, hallucination).

The ECG will classically show a shortened QT interval, and this can progress to cause complete AV nodal block and cardiac arrest.

Management

Severe hypercalcemia, or hypercalcemia with ECG changes or severe symptoms, warrants aggressive therapy.

The first step in therapy is aggressive IV fluid administration with normal saline (a rate of 200ml/h is often recommended in the first instance, provided there are no risk factors for circulatory overload). Depending on the severity, IV bisphosphonate therapy will also be considered.6 These patients should be escalated to senior doctors early for management guidance.

Mild or moderate hypercalcemia with no ECG changes or symptoms can be treated much less aggressively, often with IV fluids alone in the first instance, whilst awaiting further investigations as to the underlying cause.

Always check the drug chart for medications that may be contributing (calcium/vitamin D supplements, thiazide diuretics), and send PTH levels in the blood as a first-line investigation if this is a new issue.

For more information on the symptoms, causes, and investigation of hypocalcaemia, see our dedicated guide to bone profile interpretation.

Hypophosphataemia

Hypophosphatemia is defined as serum phosphate <0.8mmol/L. It is most commonly an incidental finding. Severe hypophosphatemia may present with CNS features such as delirium, seizures and coma.

Management

Most cases of hypophosphataemia are mild and can safely be managed with oral phosphate replacement.

IV replacement is indicated if the deficiency is severe (<0.3 mmol/L) or the patient is symptomatic, alongside investigation and treatment of the underlying cause.7

For greater detail on the causes of hypophosphataemia, see our dedicated guide to the bone profile interpretation.

Hyperphosphataemia

Hyperphosphataemia is defined as serum phosphate >1.45mmol/L. Most cases of hyperphosphatemia are mild, asymptomatic and associated with chronic kidney disease.

These patients will not need urgent treatment during the on-call period.

Acute hyperphosphatemia without symptoms will generally self-resolve within 6-12 hours if renal function is normal. Intravenous saline can help accelerate phosphate excretion if the phosphate is markedly elevated. However, this should be used with caution in patients with chronic kidney disease (risk of fluid overload).

Severe hyperphosphatemia can present with altered mental status, muscle weakness, muscle pain, and even seizures. Severe cases are often also associated with significant hypocalcaemia. These patients should be urgently escalated to a senior as they may need urgent renal replacement therapy to normalise electrolytes.8

For greater detail on the causes of hyperphosphataemia, see our dedicated guide to the bone profile interpretation.

Hypomagnesaemia

Hypomagnesaemia is defined as serum magnesium <0.75 mmol/L. Severe hypomagnesaemia is defined as serum magnesium <0.4 mmol/L. Symptoms are more likely when levels fall below 0.5 mmol/L. These can range from mild weakness and confusion to serious symptoms such as tetany, arrhythmias or even seizures.

Patients with severe hypomagnesaemia, or symptoms thought to be related to hypomagnesaemia, should have IV magnesium replacement with ongoing cardiac monitoring.9 Follow your hospital protocol for IV magnesium replacement, as this can be given in various ways.

Patients with mild or moderate hypomagnesaemia can generally be treated with oral magnesium alone, most commonly magnesium aspartate 10mmol sachets twice daily.

Hypermagnesaemia

Hypermagnesaemia is defined as serum magnesium >1.5 mmol/L. Clinically significant hypermagnesaemia is rare in those with normal renal function. When present, it is usually mild and does not require any specific treatment.

As the serum magnesium level rises >2mmol/L, the incidence of symptoms starts to rise. Symptoms can begin with flushing, nausea and vomiting. However, as the magnesium level increases >4mmol/L, there will be progressive neurological impairment (drowsiness progressing to coma / respiratory depression) and risk of cardiac arrest (rare, often with levels >8mmol/L).10

At any level of hypermagnesaemia, remove any external magnesium sources (e.g. magnesium supplementation or magnesium-containing enemas). Always check a 12-lead ECG to ensure the QT interval is normal.

If the magnesium level is >2mmol/L and there are suspected symptoms related to hypermagnesaemia, this may require treatment. Initial treatment is often with IV calcium gluconate, but this should always be discussed with a senior doctor to ensure you are not missing an alternate diagnosis.

Patients with magnesium levels >4mmol/L and associated neurological impairment should be urgently discussed with senior colleagues and ultimately may require renal replacement therapy, although this is rare.11

References

- UpToDate. Clinical manifestations and treatment of hypokalemia in adults. November 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- UpToDate. Treatment and prevention of hyperkalemia in adults. Oct 2023. Available from: [LINK].

- UpToDate. Overview of the treatment of hyponatremia in adults. July 2023. Available from: [LINK].

- UpToDate. Treatment of hypernatremia in adults. Sept 2021. Available from: [LINK].

- UpToDate. Treatment of hypocalcemia. March 2023. Available at [LINK].

- UpToDate. Treatment of hypercalcemia. October 2023. Available at [LINK].

- Hypophosphatemia. December 2022. Available at [LINK].

- UpToDate. Overview of the causes and treatment of hyperphosphatemia. April 2023. Available at [LINK].

- UpToDate. Hypomagnesemia: Evaluation and Treatment. October 2023. Available at [LINK].

- Trust Clinical Guidelines Group, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust. Hypermagnesaemia in Adults – Clinical Guideline for the Treatment of. February 2011. Available at [LINK].

- UpToDate. Hypermagnesemia: Causes, symptoms, and treatment. October 2023. Available at [LINK].