- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Jaundice is a yellow discolouration of the sclerae and skin due to excess bilirubin in the blood (hyperbilirubinaemia).1

Neonatal jaundice is extremely common. Around 60% of term babies and 80% of preterm babies will develop jaundice in the first week of life.2

Although most cases are not caused by an underlying pathology, jaundice can indicate serious disease and may result in long-term morbidity and even mortality if untreated.2

Aetiology

Physiology of bilirubin metabolism

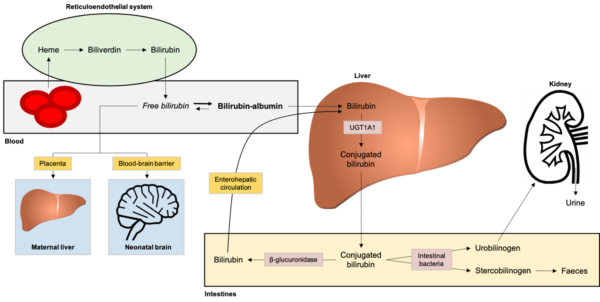

Understanding neonatal jaundice requires knowledge of bilirubin metabolism (Figure 1).3

Bilirubin is produced from the breakdown of red blood cells (RBCs). Most unconjugated bilirubin circulates bound to albumin, but some circulate as ‘free’ bilirubin, which is lipid-soluble and can cross the blood-brain barrier.

An enzyme in the liver, called UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT), converts unconjugated bilirubin to conjugated bilirubin by adding an amino acid. Conjugated bilirubin is water-soluble but lipid insoluble, so it cannot cross the blood-brain barrier.

Conjugated bilirubin is transported to the small intestines via the biliary system and some is converted back to unconjugated bilirubin by the enzyme β-glucuronidase. This unconjugated bilirubin re-enters the circulating pool of bilirubin via the enterohepatic circulation.

The remaining conjugated bilirubin is metabolised by intestinal bacteria to produce urobilinogen and stercobilinogen. Urobilinogen is oxidised to urobilin, which gives urine its yellow colour. Stercobilinogen is oxidised to stercobilin, which gives faeces its brown colour.

Normal ‘physiological’ jaundice

Jaundice is often a normal phenomenon in neonates, with no underlying pathology.1 Physiological jaundice is unconjugated and usually presents on the second or third day of life.2

Mechanisms behind physiological jaundice include:3

- Shorter lifespan of neonatal red blood cells

- Immature liver function at birth

- A relatively high concentration of β-glucuronidase in the small intestine

Some neonates are more prone to jaundice:2

- Preterm babies: tend to have higher bilirubin levels and more prolonged jaundice than term infants.

- Breastfed babies: experience more marked and prolonged jaundice than formula-fed infants for reasons that are not completely understood. Prolonged jaundice in breastfed babies is sometimes referred to as ‘breast milk’ jaundice.

- Babies with significant bruising or cephalohaematoma: which can occur in difficult deliveries. The breakdown of RBCs within the cephalohaematoma causes higher bilirubin levels and predisposes to jaundice.

Pathological causes of neonatal jaundice

While most cases of neonatal jaundice do not have a pathological cause, many underlying diseases can present with jaundice.2

Unconjugated jaundice

Unconjugated jaundice can be caused by neonatal sepsis, haemolysis, or endocrine/metabolic disorders.

Haemolytic causes include:5,6

- Haemolytic disease of the newborn: caused by maternal Rhesus or ABO antibodies against the baby’s RBCs

- Hereditary spherocytosis: an inherited disease where defects in RBC skeletal proteins cause RBCs to assume a spherical shape with a reduced lifespan

- Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency: an X-linked recessive condition where lack of G6PD makes RBCs susceptible to oxidative damage and haemolysis. It can cause severe neonatal jaundice.

Endocrine or metabolic causes include:7

- Gilbert’s syndrome: an autosomal recessive disorder with reduced UGT enzyme activity in the liver. This causes reduced ability to conjugate bilirubin, resulting in mild episodes of jaundice throughout life in response to certain triggers.

- Crigler-Najjar syndrome: a rare autosomal recessive disorder where no functioning UGT is produced in the liver. It presents with severe, prolonged jaundice that often results in neurological damage and death within one year of life.

- Congenital hypothyroidism

- Galactosaemia and other inborn errors of metabolism (these may also cause conjugated jaundice)

Conjugated jaundice

Causes of conjugated jaundice include:

- Biliary atresia: early diagnosis and treatment of this condition is vital (see below)

- Neonatal hepatitis (e.g. cytomegalovirus, hepatitis B, rubella or herpes simplex virus)

- Galactosaemia and other inborn errors of metabolism

Biliary atresia

Biliary atresia is a congenital inflammatory disease of unknown cause. It results in complete obliteration of the extra-hepatic bile ducts after birth. If untreated, it progresses to liver cirrhosis and death.8

It presents with prolonged conjugated jaundice, pale stools and dark urine. A liver ultrasound scan is helpful, but a percutaneous biopsy is the gold-standard diagnostic method. Biliary atresia is treated with a portoenterostomy (Kasai procedure) or liver transplantation.8

All babies with conjugated jaundice need urgent further investigation and referral to a paediatric liver specialist. The longer biliary atresia goes untreated, the more irreversible damage is done to the liver.

Clinical features

All babies should be examined for jaundice at every opportunity.

History

The history may reveal risk factors for neonatal jaundice. NICE guidelines list the following risk factors for significant hyperbilirubinaemia (i.e. requiring treatment):1

- Gestational age <38 weeks

- Previous sibling with neonatal jaundice requiring phototherapy

- Mother’s intention to breastfeed exclusively

- Visible jaundice in the first 24 hours of life

Other important areas to cover in the history include:9

- Family history: a history of inherited diseases (e.g. G6PD deficiency or liver disease) or previous sibling with jaundice (suggests a higher chance of haemolytic disease of the newborn)

- Pregnancy history: congenital infections, diabetes (increases the risk of jaundice), maternal drugs (e.g. sulfonamides interfere with bilirubin-albumin binding), maternal blood group and any known antibodies

- Labour and delivery history: birth trauma (e.g. bruising or cephalohaematoma)

- Feeding history: breastfeeding or formula feeding, intake (poor intake causes delayed or infrequent stooling which increases enterohepatic circulation of bilirubin), vomiting (may be a sign of sepsis or galactosaemia)

Clinical examination

A thorough clinical examination should be performed. See the Geeky Medics guide here for further information.

To detect jaundice, the baby should be naked and examined in bright, natural light (Figure 2).

Jaundice is often most obvious in the sclerae and gums. The skin can be lightly pressed, which may reveal jaundice in the blanched skin.1

It is important to assess if the baby is clinically well and whether there are any signs of infection or bilirubin encephalopathy (see below).

Examination should include inspecting the nappy for stools and urine. Pale, chalky stools and dark urine suggest conjugated jaundice and an underlying pathological cause such as biliary atresia.1,2

Jaundice in the first 24 hours of life and conjugated jaundice are always pathological and require urgent investigation for an underlying cause.1,2

Investigations

Measuring the bilirubin level

It is important to measure the bilirubin level for all babies who are visibly jaundiced. This can be achieved with:

- Transcutaneous bilirubinometry: a bedside test that evaluates light absorption through the skin over the forehead or sternum.2 It is not as accurate as serum bilirubin but is non-invasive.

- Serum bilirubin: NICE guidelines recommend that serum levels are used for babies who are visibly jaundiced <24 hours of life, with a gestational age <35 weeks, or when monitoring bilirubin after starting treatment.1 Serum bilirubin is also used to confirm a high transcutaneous level.

Identifying an underlying cause

Not all jaundiced babies require investigation for an underlying cause.

NICE guidelines recommend the following investigations are performed for babies who require treatment for jaundice:1

- Blood packed cell volume (PCV): to assess the degree of anaemia or polycythaemia

- Blood group of the mother and baby: to assess for incompatibility (i.e. haemolytic disease of the newborn)

- Direct antiglobulin test (DAT, aka Coombs’ test): a positive DAT suggests immune-mediated haemolysis (i.e. haemolytic disease of the newborn). A negative DAT suggests non-immune-mediated haemolysis (e.g. hereditary spherocytosis or G6PD deficiency)

Other laboratory investigations to consider include:1

- Full blood count (FBC) and blood film: to assess the morphology of the RBCs (e.g. in hereditary spherocytosis)

- G6PD levels: especially if there is a positive family history or in Mediterranean, Asian or African ethnicity

- Blood, urine and/or cerebrospinal fluid cultures: if there are signs of infection

More specialist tests may be needed to diagnose certain diseases, these include:2

- Liver ultrasound or percutaneous biopsy: biliary atresia

- Genetic testing: Gilbert’s syndrome or Crigler-Najjar syndrome

- Urinary reducing substances: galactosaemia

Management

There are two main methods to treat neonatal jaundice: phototherapy and exchange transfusion.1 Most babies will respond well to phototherapy and exchange transfusions are rarely used.

The decision to begin treatment is based on treatment threshold graphs produced by NICE. There are different graphs for different gestations and preterm babies have a lower threshold for starting treatment.

Phototherapy

In phototherapy, the baby is placed under blue-green light (Figure 3). The light converts the neurotoxic unconjugated bilirubin to a harmless, water-soluble isomer called lumirubin, which is readily excreted in the bile and urine.3

Phototherapy can be given in different ways (e.g. with an overhead light or a blanket that wraps around the baby) and the intensity of the lights can be varied.

Exchange transfusion

Exchange transfusions reduce bilirubin levels by swapping the baby’s blood with donor blood. This may be required for dangerously high levels of bilirubin.1

A small volume of the baby’s blood is removed as donor blood is injected. This process is repeated many times. As well as lowering serum bilirubin levels, exchange transfusions can also remove a significant proportion of the antibodies responsible for haemolytic disease of the newborn.

Exchange transfusions have a high rate of complications, so they are reserved for the most severe cases of neonatal jaundice which are not responding to intense phototherapy or where babies are showing signs of acute bilirubin encephalopathy.2

Complications

The main complication is bilirubin encephalopathy (kernicterus), which can occur with high levels of unconjugated bilirubin.

Bilirubin encephalopathy

Unconjugated bilirubin is lipid-soluble and can cross the blood-brain barrier. It accumulates in the brainstem nuclei, basal ganglia, hippocampus and cerebellum and is neurotoxic.2,3

Bilirubin encephalopathy initially presents with lethargy, hypotonia and poor suck reflex. This progresses to hypertonia, opisthotonos, fever, seizures and a high-pitched cry.

Early damage to the brain can be reversible but if hyperbilirubinemia is pronounced or prolonged then it can lead to cerebral palsy, sensorineural hearing loss or cognitive impairment.2

Key points

- Jaundice is a yellow discolouration of the sclerae and skin due to excess bilirubin in the blood.

- Neonatal jaundice is extremely common and is often a normal phenomenon, but pathological causes must be excluded.

- Important causes include sepsis, haemolytic disease of the newborn and biliary atresia.

- Jaundice in the first 24 hours of life and conjugated jaundice require urgent investigation.

- Bilirubin levels can be measured with transcutaneous bilirubinometry or a serum sample.

- If treatment is required, phototherapy is generally safe and effective but sometimes exchange transfusions are required.

- The main complication is bilirubin encephalopathy (kernicterus), which occurs in unconjugated jaundice and can be life-threatening or can cause long-term morbidity.

Reviewer

Dr Stewart Cox

ST3 Paediatrics

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. CG95: Jaundice in newborn babies under 28 days. Published 2010, updated 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- Ives NK, Mieli-Vergani G, Hadzic N, et al. Gastroenterology. In: Rennie JM (ed.) Rennie and Roberton’s Textbook of Neonatology, 5th London, UK: Churchill Livingstone. Published 2012.

- Cashore WJ. Neonatal Bilirubin Metabolism. In: Polin RA, Abman, SH, Rowitch DH, Benitz WE, and Fox WW (edds.) Fetal and Neonatal Physiology, 5th Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. Published 2017.

- Samuel Neal, Jmarchn, DataBase Center for Life Science (DBCLS). Bilirubin metabolism diagram. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Patient UK. Hereditary Spherocytosis. Published 2015. Available from: [LINK]

- Patient UK. Glucose-6-phospate Dehydrogenase Deficiency. Published 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Gilbert’s syndrome. Published 2015. Available from: [LINK]

- Patient UK. Biliary Atresia. Published 2014. Available from: [LINK]

- Stark AR and Bhutani VK. Neonatal Hyperbilirubinaemia. In: Eichenwald EC, Hansen AR, Martin C, et al. (eds.) Cloherty and Stark’s manual of neonatal care, 8th Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer. Published 2017.

- treehouse1977. Poorly baby. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- treehouse1977. Phototherapy. Licence: [CC BY-SA]