- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Table of Contents

Introduction

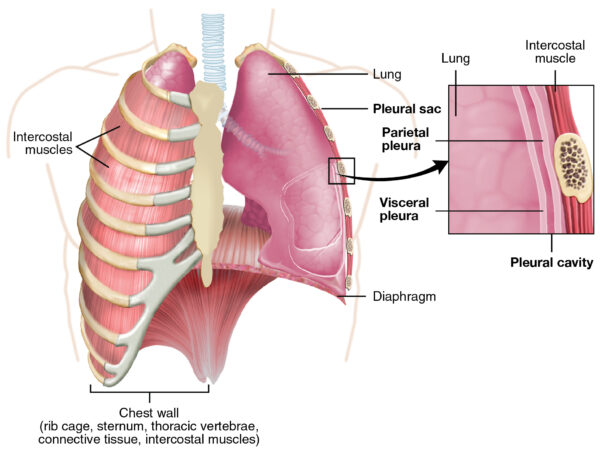

A pleural effusion is the accumulation of fluid in the pleural space. The pleural space is the area between the visceral and parietal pleura.1

Aetiology

Anatomy

The lungs are surrounded by the pleural membrane. This is a serous membrane divided into the visceral pleura (lines the lungs) and parietal pleura (lines the internal thoracic cavity).

The potential space between the visceral and parietal pleura contains a small amount of lubricating serous fluid.

The serous fluid allows the visceral and parietal pleura to slide over each other during respiration and creates surface tension between the two layers.

Pleural effusions occur when fluid accumulates in the pleural space.

Classification

Pleural effusions are usually classified as transudative or exudative.

Transudates have a low protein level of <25g/L. Fluid accumulates due to a disruption in hydrostatic and oncotic pressures.

Exudates have a high protein level of >35g/L. Fluid accumulates due to increased pleural and capillary permeability.1

Table 1. An overview of the causes of pleural effusions.1

| Type | Causes |

|

Transudative |

Common: ‘the failures’: heart failure, cirrhosis (liver failure) Less common: hypoalbuminemia, nephrotic syndrome, peritoneal dialysis, hypothyroidism Rare: Meigs’ syndrome (benign ovarian tumour, ascites, pleural effusion) |

|

Exudative |

Common: infection (parapneumonic, tuberculosis), malignancy Less common: pulmonary infarction, autoimmune diseases (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis), pancreatitis, post-myocardial infarction (Dressler’s syndrome), post coronary artery bypass grafting, asbestos Rare: yellow nail syndrome, drugs (methotrexate, amiodarone, nitrofurantoin, phenytoin) |

|

Other |

Haemothorax: blood in the pleural space Empyema: pus in the pleural space Chylothorax: chyle in the pleural space due to disruption of the thoracic duct (due to a neoplasm, trauma or infection/inflammation) |

Clinical features

History

Small and moderate pleural effusions are commonly asymptomatic. As the pleural effusion increases in size, symptoms begin to develop.

Typical symptoms of a pleural effusion include:1

- Breathlessness

- Cough

- Pleuritic chest pain

Other important areas to cover in the history include:

- Symptoms suggestive of lung cancer: haemoptysis, weight loss

- Symptoms suggestive of heart failure: orthopnoea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea, leg swelling

- Symptoms suggestive of infection: productive cough, fever

- Social history: smoking history (lung cancer risk), asbestos exposure (mesothelioma)

Clinical examination

In the context of a pleural effusion, a thorough respiratory examination is required.

On peripheral inspection lookout for nicotine staining of fingers, clubbing (lung cancer), evidence of joint deformity (rheumatoid arthritis) and signs of fluid overload (heart failure).

On closer inspection of the chest, a larger pleural effusion may cause reduced chest movement on the affected side.

Palpation may reveal tracheal deviation away from the affected side and reduced chest expansion on the affected side. There may also be reduced tactile vocal fremitus over the pleural effusion.

On percussion, a pleural effusion classically sounds ‘stony’ dull. When auscultating, breath sounds and vocal resonance are reduced or absent over an effusion.

Differential diagnoses

Breathlessness, cough and pleuritic chest pain are typical presenting features of a pleural effusion but important differentials to consider include:

- Infection: such as pneumonia or tuberculosis

- Malignancy without effusion

- Pulmonary embolism

- Pneumothorax

Investigations

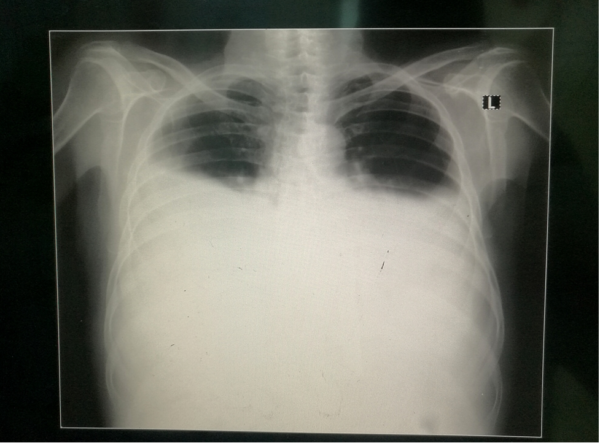

Chest X-ray is a useful initial investigation when suspecting a pleural effusion, however, it is important to also consider other investigations to ascertain the aetiology of the effusion.

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations include:

- ECG: to look for a cardiac cause of chest pain and breathlessness or signs of right heart strain which may indicate a pulmonary embolism.

- Urine dip: to assess for proteinuria which may indicate nephrotic syndrome.

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:

- FBC/CRP/blood cultures: to look for infection

- Arterial blood gas: if oxygenation if affected

- D-dimer: if a pulmonary embolism is suspected

- LFTs, U&Es, albumin, coagulation profile: to look for liver and renal disease

- Amylase: if pancreatitis is suspected

- TFTs: if hypothyroidism is suspected

Imaging

A chest X-ray is the first-line imaging investigation of choice. This is useful to assess a pleural effusion and estimate its size. A unilateral effusion is typically exudative whereas bilateral effusions are typically transudative.

50ml of pleural fluid can cause costophrenic blunting, but >200ml fluid is needed to be visible on PA film.1

A chest X-ray is also useful to assess for the underlying aetiology of the pleural effusion. Look for consolidation (infection), malignancy, cardiomegaly (cardiac failure) and pleural plaques (asbestos exposure).

Other relevant imaging investigations include:

- CT or ultrasound chest: to further characterise pleural effusion and investigate for an underlying cause.

- Echocardiogram: to look for signs of heart failure or right heart strain (which may suggest pulmonary embolism).

Other investigations

If a unilateral pleural effusion is thought to be exudative, British Thoracic Society guidelines suggest pleural fluid aspiration (diagnostic) which is usually performed under ultrasound guidance.5

Pleural aspirations are not routinely carried out for bilateral effusions with features suggestive of a transudate.5

Medical thoracoscopy can be used to aid diagnosis in some circumstances. It involves visualising and taking a biopsy of the pleura using a thoracoscope under local anaesthetic.

Diagnosis

Pleural fluid should be sent for biochemistry (protein, LDH and glucose), microbiology (gram stain and culture) and cytology. More specialist tests may be needed depending on the likely cause of the pleural effusion.

If pleural fluid protein is 25-35g/L, Light’s criteria are used to distinguish transudative from exudative pleural effusions.

Light’s criteria summary

The fluid is an exudate if one or more of the following criteria are met:6

- Pleural fluid protein divided by serum protein is >0.5

- Pleural fluid LDH divided by serum LDH is >0.6

- Pleural fluid LDH is >⅔ the upper limit of the laboratory normal value for serum LDH

The appearance of the pleural fluid should be noted: purulent fluid suggests infection, bloody fluid may suggest malignancy, pulmonary embolism or trauma.

Fluid pH can be analysed in a blood gas machine if the fluid is not purulent. A fluid pH < 7.3 can indicate malignancy, pleural infection, rheumatoid arthritis, tuberculosis and oesophageal rupture. In parapneumonic effusions, pH <7.2 indicates drainage is needed.5

Management

The main aim of management is to treat the underlying cause of the pleural effusion.

Medical management

In smaller pleural effusions without symptoms, management may simply involve observation.

Some examples of appropriate medical treatment in exudative or larger transudative effusions are:

- Diuretics in heart failure

- Antibiotics in infection

Symptomatic patients with larger pleural effusions may benefit from pleural fluid aspiration (therapeutic) or chest drain insertion under ultrasound guidance.

If the pleural effusion reaccumulates, the following options may be considered:

- Long term indwelling chest drain

- Pleurodesis (by chest drain or medical thoracoscopy)

Surgical management

Some patients may need to have further investigation and management of their effusion by a thoracic surgeon who may carry out video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS).

Complications

Complications vary depending on the cause of the pleural effusion.

Larger pleural effusions may cause increasing respiratory compromise. In parapneumonic effusions, complications may include empyema and sepsis.

Complications, such as pneumothoraces, may relate to pleural procedures carried out during the diagnosis and treatment of a pleural effusion.

Patients with malignancy or pneumonia have a poorer prognosis if a pleural effusion develops.7

Key points

- A pleural effusion is the presence of an abnormal amount of fluid in the pleural space (a potential space between the visceral and parietal pleura).

- Pleural effusions can be transudative (lower protein/LDH) or exudative (higher protein/LDH).

- Transudates are commonly due to heart failure and cirrhosis, whereas exudates are commonly caused by infection and malignancy.

- Typical symptoms include breathlessness, cough and pleuritic chest pain. Clinical findings may include reduced chest expansion, reduced air entry and a stony dull percussion note on the affected side.

- Chest X-ray and pleural aspiration are important investigations to assess and identify the aetiology of a pleural effusion.

- On obtaining a pleural fluid sample, pleural fluid appearance and pH should be checked. Fluid should then be sent to biochemistry (for protein and LDH), microbiology (gram stain and culture) and cytology.

- The main aim of management is to treat the underlying cause of the effusion.

- Smaller transudative effusions can often be managed conservatively with observation. Larger effusions may need therapeutic pleural aspiration.

- Complications relate to the underlying cause, but larger pleural effusions can cause respiratory compromise.

Reviewer

Dr Samantha Cockburn

Respiratory Registrar

North Devon District Hospital

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References:

- C. Tidy for Patient.info. Pleural Effusion. Published in 2016. Available from: [LINK].

- OpenStax. The lung pleurae. Licence: [CC-BY]. Available from: [LINK].

- Clinical Cases. Left-sided pleural effusion. Licence: [CC-BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK].

- Sara Nabih. Bilateral pleural effusions. Licence: [CC-BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK].

- British Thoracic Society. Investigation of a unilateral pleural effusion in adults: British Thoracic Society pleural disease guideline 2010. Published in 2010. Available from: [LINK].

- R. Light et al. Pleural Effusions: The Diagnostic Separation of Transudates and Exudates. Published in 1972. Available from: [LINK].

- S. Crane and C. Wearmouth for RCEM Learning. Pleural Effusion. Published in 2011. Available from: [LINK].