- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Osteoporosis means “porous bone“. It is a progressive, systemic skeletal disorder characterised by reduced bone density and defects within the microstructure of bone. This means that patients with osteoporosis are at an increased risk of fractures, although the condition remains asymptomatic until a fracture occurs.

The global prevalence of osteoporosis is around 18%, although it is more common in women, older adults, and people with certain risk factors.1

Osteopenia is a precursor to osteoporosis and refers to a less severe reduction in bone density.

Aetiology

Many factors contribute to our bones’ strength, such as the size and shape of the bone, the rate of bone turnover, and mineralisation. Osteoporosis is a disease that affects all of the bones in the body and leads to reduced bone strength due to a reduction in bone mass and mineral density.

Bone is constantly being remodelled based on mechanical stress and systemic factors in the body. The cells responsible for the resorption of bone are osteoclasts, and osteoblasts are responsible for producing new bone matrix. Osteocytes regulate the balance between the activity of these cells.

Osteoporosis occurs when there is a mismatch between the activity of these cells and the demand for bone remodelling, either through increased activity of osteoclasts or reduced activity of osteoblasts.

This eventually leads to lower bone density and quality, which increases the risk of fractures. Osteoporotic fractures are also known as “fragility fractures” because they occur from mechanical forces or trauma that would not normally cause a fracture.

Risk factors

There are numerous risk factors for osteoporosis.2

General risk factors include:2

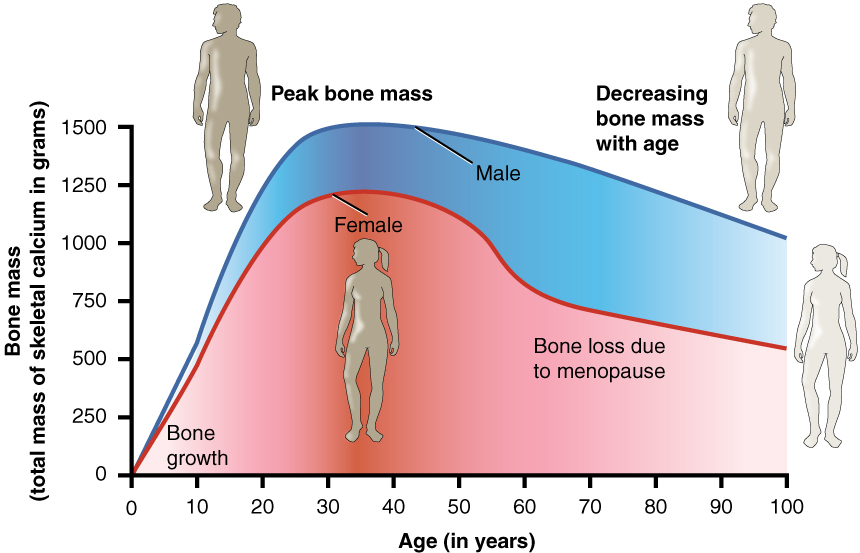

- Increasing age: bone density naturally decreases with age, so older patients are more likely to have reduced bone density (Figure 1)

- Female sex

- Post-menopause: due to changes in oestrogen levels; the risk is highest post-menopause as the relative deficiency of oestrogen leads to excess bone resorption

- Reduced mobility and activity: weight-bearing places stress on bones, which leads to increase bone strength through remodelling, the less active a patient is, the less this occurs

- Low BMI (<18.5kg/m2)

- Smoking

- Alcohol intake >3 units/day

- Parental history of hip fracture

- Previous fragility fracture

Medical conditions which increase the risk of osteoporosis include:2

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Primary hyperparathyroidism

- Chronic kidney disease

- Gastrointestinal disease (e.g. Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, coeliac disease)

- Hyperthyroidism

- Chronic liver disease

Medications which increase the risk of osteoporosis include:2

- Corticosteroids: any dose orally for > 3 months, but the risk increases significantly at doses > 7.5mg prednisolone/day

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)

- Anti-epileptics

- Anti-oestrogens

Clinical features

History

Osteoporosis remains asymptomatic until a fracture occurs, meaning the disease can become established before it is diagnosed.

A fragility fracture is defined as a low-impact fracture from a standing height or less. The most common sites of fragility fracture are:3

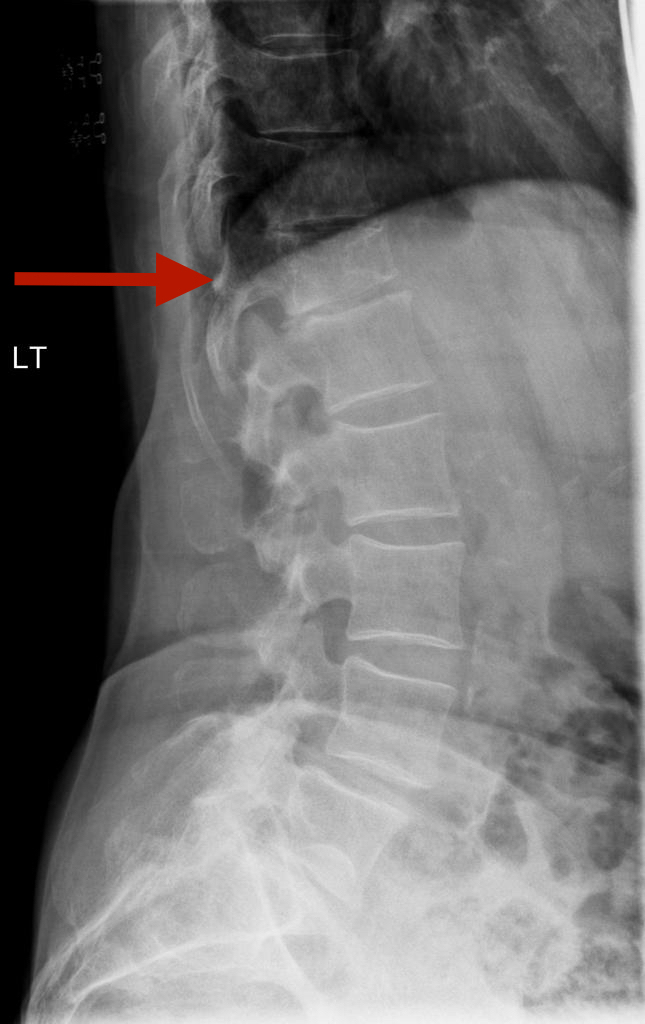

- Vertebral: although a large number of vertebral fractures are asymptomatic

- Hip (proximal femur)

- Wrist (distal radius)

However, they can occur at other sites, such as the humerus, pelvis, and ribs.

Important areas to cover in the history are the mechanism of injury and risk factors for osteoporosis.

Clinical examination

Osteoporosis itself will generally not cause specific findings on clinical examination. Patients with vertebral fractures may have hyperkyphosis of the spine due to multiple vertebral body compression fractures (“Dowager’s hump”).

There may be signs of risk factors for osteoporosis (e.g. tar staining in patients who smoke or joint swelling in patients with rheumatoid arthritis).

Investigations

Assessing fracture risk

The Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX®) score was developed to help assess the risk of fractures in patients suspected of having osteoporosis, either due to risk factors or following a fragility fracture.

FRAX calculates the 10-year fracture probability, which can be used to help guide further investigation and management.

The FRAX score takes into account the following factors:4

- Age

- Sex

- BMI

- Previous fractures

- Parental hip fracture

- Smoking status

- Alcohol consumption

- Glucocorticoid use

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Secondary osteoporosis

If a patient has already had their bone density assessed, then the FRAX score considers this to better estimate fracture probability.

When to assess fracture risk

NICE advises that the following patient groups should have a fracture risk assessment:3

- All women aged 65 years and over

- All men aged 75 years and over

- Women aged under 65 years, and men aged under 75 years with risk factors (those listed above)

Generally, risk assessment is not recommended for people under 50 unless they have significant risk factors, for example, current/frequent use of oral glucocorticoids, untreated premature menopause, or previous fragility fracture.

An alternative to the FRAX score is the QFracture risk calculator, which considers similar risk factors.5

Interpreting fracture risk

FRAX and QFracture produce a risk score for hip fractures and other major osteoporotic fractures (spine, wrist, or shoulder) over the next 10 years.6

Table 1. Fracture risk with QFracture and FRAX.

| Risk | QFracture | FRAX |

| High risk | >10% | Red zone of risk chart |

| Intermediate risk | Close to, but <10% | Orange zone of risk chart |

| Low risk | <10% | Green zone of risk chart |

This is used to guide the management plan:6

- Low risk: measuring bone mineral density (BMD) is not required; give lifestyle advice and reassurance and monitor risk factors

- Intermediate risk: arrange a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan and recalculate the risk score with BMD taken into account

- High risk: offer treatment, and arrange a DXA scan to measure BMD to establish a baseline and guide treatment

Risk assessment tools may underestimate the fracture risk in certain populations:

- Patients over 80 years old,

- Multiple previous fragility fractures

- Patients taking oral glucocorticoids (>7.5mg prednisolone or equivalent for 3 months or more)

Bone density measurement

BMD can be measured using a DXA scan, a specialised type of X-Ray that can indicate the density of bone depending on how much radiation is absorbed.

Any bone in the body can be used, but the two regions typically used for osteoporosis diagnosis are the femoral neck and spine. The femoral neck BMD is generally considered the gold standard diagnostic test.

A DXA scan produces several different scores:

- T-score: the number of standard deviations the patient’s bone density is from the mean bone density of a 30-year-old adult

- Z-score: the number of standard deviations the patient’s bone density is from the mean bone density of age and gender-matched control

Generally, a DXA scan should not be repeated for two years unless the risk profile has changed significantly. They can also be used to monitor response to treatment in patients with known osteoporosis, with repeated scans taking place every 2-5 years.

Other investigations

Depending on the clinical context, other investigations may be useful to identify underlying causes of osteoporosis and exclude differential diagnoses.

X-Rays are useful for detecting fragility fractures, particularly vertebral fractures, or can show osteopenia.1

Relevant laboratory investigations include:

- Bone profile: usually normal in osteoporosis, raised ALP/low phosphate can indicate osteomalacia

- Urea & electrolytes: screening for chronic kidney disease as a cause of osteoporosis

- Vitamin D: if low, can increase the risk of osteoporosis

- PTH: screening for hyperparathyroidism as a cause of osteoporosis

- Thyroid function tests: screening for hyperthyroidism as a cause of osteoporosis

- Testosterone: screening for hypogonadism as a cause of osteoporosis

- Serum immunoglobulins and paraproteins: if abnormal, may indicate myeloma

Diagnosis

Osteoporosis can be diagnosed based on a history of a previous fragility fracture or a low BMD identified on a DXA scan.1

While both the T-score and Z-score are given on a DXA scan report, the T-score is used for diagnosis.

Table 2. T-score interpretation.

| T-score | Diagnosis |

| > -1 | Normal bone mineral density |

| -1 to -2.5 | Osteopenia |

| < -2.5 | Osteoporosis |

| < -2.5 AND previous fracture | Severe osteoporosis |

Management

All patients who undergo fracture risk assessment should be given lifestyle advice, as this may help prevent osteoporosis and fractures in low-risk patients.

Pharmacological treatment should be offered for those diagnosed with osteoporosis, and various medications are available depending on the patient’s risk factors, history, and personal preference.

It is also important to address any modifiable risk factors (e.g., offering hormone replacement therapy for women with premature menopause).

Lifestyle advice

Lifestyle modifications which can increase BMD and decrease fracture risk include:

- Regular exercise, particularly strength-based and weight-bearing exercise: swimming and cycling do not improve bone density

- Stopping smoking

- Reducing alcohol intake to recommended limits

- Adequate dietary calcium intake (minimum 700mg/day)

- Adequate vitamin D intake

- Maintaining a healthy weight

Calcium and vitamin D

It is important to ensure that patients with osteoporosis have adequate calcium and vitamin D levels, as the risk of fracture increases when low due to their effect on bone metabolism.

Vitamin D is especially important as many people in the northern hemisphere are deficient.

Patients with vitamin D levels. below 50nmol/L should be offered treatment:7

- Rapid correction: 300,000 IU vitamin D3 over 6-10 weeks in divided doses, followed by maintenance vitamin D

- Maintenance: 800-2,000 IU vitamin D3/day

Most patients can meet their calcium intake through diet. If not, this can be supplemented. Calcium is often combined with vitamin D, such as Calcichew-D3 (1000mg calcium and 800 IU vitamin D).

Bisphosphonates

Oral bisphosphonates are generally considered the first-line treatment for patients with osteoporosis:

- Alendronic acid (10mg daily or 70mg weekly)

- Ibandronic acid

- Risedronate sodium (5mg daily or 35mg weekly)

Alendronic acid is generally given initially. Alternatives can be tried if the patient experiences side effects. It is important to counsel patients before starting any bisphosphonate treatment.

Bisphosphonate counselling

Important points to cover when starting patients on bisphosphonates include:

- Oral bisphosphonates should always be taken on an empty stomach

- Tablets should be swallowed whole with a whole glass of water in an upright position, and remain upright for 30 minutes after taking the medication

- Potential side effects include gastrointestinal upset (dyspepsia, reflux), atypical fractures and osteonecrosis of the jaw (jaw pain, swelling and erythema)

- A dental check-up is advised before starting bisphosphonates: any dental work should be performed before or as soon as possible after starting bisphosphonates.

For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to bisphosphonate counselling.

If a patient cannot take oral bisphosphonates due to contraindications or experiences side effects, then a specialist referral should be considered. Further treatment options include zoledronic acid (5mg), an IV bisphosphonate that can be given once per year.

Non-bisphosphonate treatment

There are several other specialist treatment options available, and different options will be available depending on the age, sex, and BMD of the patient.

Denosumab

Denosumab is a monoclonal antibody that binds to RANKL, reducing osteoclast activity. It is given every six months as a subcutaneous injection.

It can be given as the first-line treatment for postmenopausal women who cannot take bisphosphonates and in men who cannot take bisphosphonates or teriparatide. It is generally considered a third-line treatment for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis.

Calcium and vitamin D levels must be adequate before starting denosumab, and it carries the risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw.

When stopping denosumab, there is a large increase in osteoclast activity (the rebound effect). This means patients must take a bisphosphonate for 1-2 years after stopping denosumab to prevent rapid bone loss and subsequent fractures.

Teriparatide

Teriparatide is a synthetic form of parathyroid hormone which increases new bone formation. It is given as a daily subcutaneous injection and can generally be given for up to 2 years. A course of teriparatide can only be given once to a patient and should not be repeated.

It is generally given as second-line treatment for patients at very high risk of fracture or who have continued to sustain fractures or experience further decreases in BMD while on treatment for osteoporosis (bisphosphonates or denosumab). Teriparatide is generally thought to be most effective for those with existing vertebral fractures.

As with denosumab, there is also a risk of a rebound effect when stopping teriparatide, meaning that patients will need to transition to an alternative treatment, usually bisphosphonates or denosumab.

Other options

Other treatment options for osteoporosis include:

- Raloxifene: a selective oestrogen receptor modulator (SERM) that can be prescribed for postmenopausal women who cannot tolerate other treatment options. It also reduces the risk of oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer but has an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE).

- Hormone-replacement therapy: should be considered to prevent osteoporosis in women who undergo premature menopause. However, it is important to remember that it does come with associated risks, such as increased VTE, and patients who have a uterus should only use oestrogen in combination with progestins to prevent the increased risk of endometrial cancer.

- Romosozumab: a recently approved monoclonal antibody that increases new bone formation and decreases bone resorption. It is given as a monthly subcutaneous injection for 12 months. Once the treatment course is complete, the patient will need to transition to an alternative therapy, such as bisphosphonate.

Treatment duration

When considering the duration of treatment, there is a need to balance the benefits of treatment with the potential adverse effects, particularly the risk of atypical fractures.

Factors that can be taken into consideration when deciding on the duration of treatment include:

- Which anti-osteoporosis treatment the patient is taking

- The continuing presence of risk factors

- Repeat BMD measurements: DXA scans are generally repeated every 2-5 years

- Measurement of bone turnover markers

- Incidence of any new fragility fractures

For bisphosphonates, the initial length of treatment is typically five years for oral bisphosphonates and three years for IV zoledronic acid.

At this point, the patient should be reassessed. If the patient falls below the treatment threshold (e.g. no further fractures, BMD T-score > -2.5), a drug holiday can be considered, with another review after two years.8

Otherwise, the patient should continue treatment (up to 10 years for oral treatments and up to 6 years for IV). The following patients are likely to require ongoing treatment:

- Age >75

- Previous hip or vertebral fracture

- Taking oral glucocorticoids (7.5mg prednisolone/day or equivalent)

- One or more low-trauma fractures during treatment (once poor adherence is excluded)

- BMD T-score < -2.5

Bisphosphonate treatment can potentially continue under specialist guidance, but the patient should be aware of the significantly increased risk of atypical fractures.

Treatments such as denosumab and teriparatide should not be stopped without specialist input due to the risk of rebound fractures.

Complications

The major complication of osteoporosis is fragility fractures:

- Hip fractures: a significant cause of disability and mortality, only 30% of patients fully recover

- Rib fractures

- Wrist fractures

- Vertebral fractures: a significant cause of long-term pain and disability, 80% of patients with vertebral fractures still experience significant pain after 12 months. One vertebral fracture also significantly increases the risk of subsequent vertebral fracture.

Patients can develop chronic pain due to fractures, significantly impacting their quality of life.

Other treatment-related complications include:

- Atypical fractures due to bisphosphonate treatment

- Osteonecrosis of the jaw due to bisphosphonate treatment

- Venous thromboembolism due to hormone replacement therapy or raloxifene treatment

Key points

- Osteoporosis is a systemic disease of the bone characterised by reduced bone density and increased risk of fractures

- It is most common in post-menopausal women, although there are a large number of risk factors for the disease

- The disease is asymptomatic until a patient experiences a fracture as a result of the reduction in bone density

- Osteoporosis is generally diagnosed following a fragility fracture, or through the incidental finding of an asymptomatic vertebral fracture

- Patients with suspected osteoporosis should undergo a fracture risk assessment to guide further investigation and management

- The gold standard diagnostic investigation is the DXA scan

- A bone mineral density T-score of <-2.5 is diagnostic for osteporosis

- Management of osteoporosis includes addressing risk factors, lifestyle measures, and medication such as bisphosphonates to increase bone density.

- Complications include fragility fractures, reduced quality of life, and chronic pain.

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- BMJ Best Practice. Osteoporosis. Published 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- Patient.co.uk. Osteoporosis (Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment). Published 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- NICE CKS. Osteoporosis – prevention of fragility fractures. Published 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- FRAX. Fracture Risk Assessment Tool. Published 2011. Available from: [LINK]

- ClinRisk. QFracture 2016 risk calculator. Published 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- Patient.co.uk. Osteoporosis Risk Assessment and Primary Prevention. Published 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- National Osteoporosis Society. Vitamin D and Bone Health: A Practical Clinical Guideline for Patient Management. Published 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- Royal Osteoporosis Society. Duration of Osteoporosis Treatment. Published 2018. Available from: [LINK]

Image references

- Figure 1. OpenStax College. Age and Bone Mass. License: [CC BY]

- Figure 2. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Case courtesy of Usman Bashir, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 19198. License: [CC BY-NC-SA]