- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Shoulder pain is a common complaint, with an estimated point prevalence of 6.9-26%.1 Shoulder impingement refers to when the soft tissue structures around the shoulder joint become trapped, causing damage and pain.

Subacromial impingement syndrome (SIS) is by far the most common variety of shoulder impingement and accounts for approximately 36% of shoulder pain diagnoses.2

SIS refers to a spectrum of pathology associated with the compression of and damage to the rotator cuff tendons as they pass through the subacromial space.3

Aetiology

Anatomy

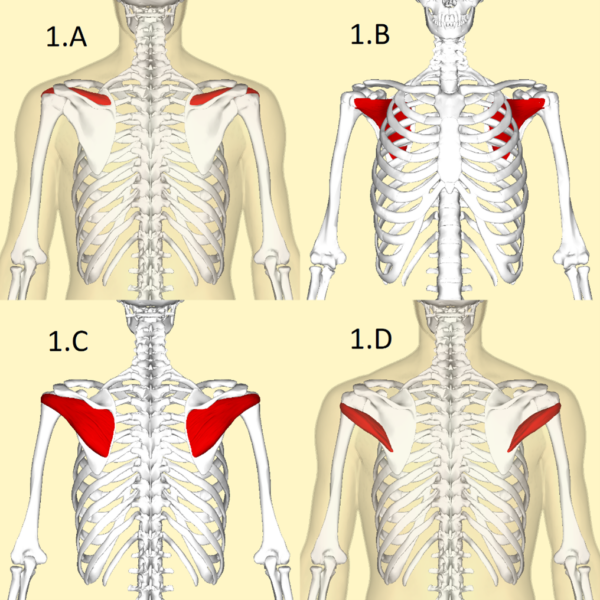

The rotator cuff stabilises the humeral head against the glenoid to form the glenohumeral joint and controls many of the movements possible at the shoulder. It is comprised of four muscles: the subscapularis, teres minor, infraspinatus, and supraspinatus.3

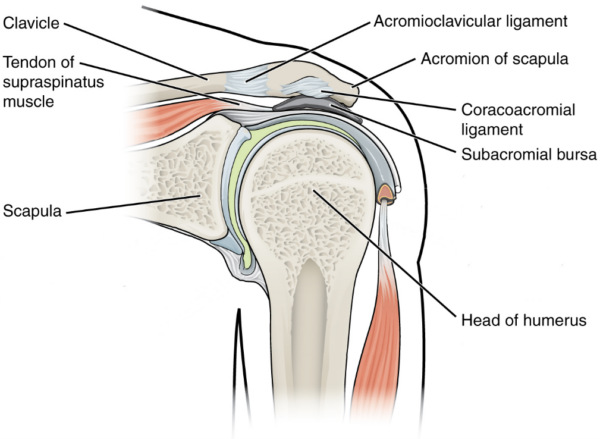

The rotator cuff tendons pass through the subacromial space (along with the long head of the biceps) prior to their attachment to the proximal humerus. Their passage through this space is lubricated by the subacromial bursa, which lies between the tendons and the overlying acromion.5

The subacromial space is bounded by:6

- The coracoacromial ligaments and acromioclavicular joint

- The anterior edge and under-surface of the acromion

- The humeral head

The supraspinatus tendon is commonly implicated in the pathology of SIS as it runs directly beneath the overhanging acromion, and so is especially predisposed to damage.

For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to the intrinsic muscles of the shoulder.

Pathophysiology

Two key mechanisms have been proposed as to the underlying mechanism behind SIS development: extrinsic compression and intrinsic degeneration. The relationship between the two concepts is still a matter of debate.

Extrinsic compression5,8,9

This relates to direct compression of the rotator cuff tendons against the surrounding structures, primarily due to established anatomic narrowing of the subacromial space, or by the superior translation of the humeral head on abduction of the shoulder.

The subacromial space can narrow due to the physical shape of the acromion, thickening of the coracoacromial ligament, or osteophytic change on the underside of the acromioclavicular joint.

Additionally, aberrant biomechanics from weakened rotator cuff musculature can result in superior translation of the humeral head and a dynamic narrowing of the subacromial space, impinging on the rotator cuff tendons.

Intrinsic degeneration10,11

Intrinsic factors are those specific to the rotator cuff tendons themselves, causing degeneration of the tendons (or impairing recovery from insult).

The poor vascularity of the supraspinatus tendon can predispose it to degenerative tears through impaired repair following microtrauma. This can lead to inflammation and pain independently, as well as to a narrowing of the subacromial space from superior humeral head translation, as outlined above.

SIS progression12

The combination of extrinsic compression and intrinsic degeneration contributes to the spectrum of clinical findings associated with SIS.

As SIS represents a spectrum of pathology associated with damage to the rotator cuff tendons, it can progress with time. The progression of this spectrum is shown below:

- Stage 1: haemorrhage and oedema surrounding the cuff tendons.

- Stage 2: rotator cuff tendinopathy: fibrosis and inflammation of the tendons.

- Stage 3: rotator cuff tears (varying degrees of severity). May have corresponding arthritic changes, or a coexistent long head of biceps tear.

Risk factors

Impingement typically starts in young patients (<25 years) but is initially reversible. Rotator cuff pathologies are not typically present until >40 years of age with progression of the condition.12

Patients with high (often occupational) levels of above-shoulder activity, especially throwing athletes, are at higher risk of developing SIS.

Different risk factors are involved in the development of extrinsic compression and intrinsic degeneration.

Table 1. An overview of risk factors for SIS.

| Causes of extrinsic compression | Mechanism |

|

Glenohumeral joint instability |

Existing rotator cuff weakness or dysfunction allows superior translocation of the humeral head, impinging on the rotator cuff tendons and subacromial bursa. |

|

Repetitive above-shoulder activity |

Repeated insult to rotator cuff tendons from compression on shoulder abduction. |

|

Acromioclavicular joint arthritis |

Osteophytes from arthritic change can reduce the subacromial space. |

|

Acromion shape |

‘Hooked’ acromion morphology can further narrow the subacromial space. |

| Causes of intrinsic degeneration | Mechanism |

|

Ageing |

Age-related degeneration and reduced elasticity of the supraspinatus tendon can predispose it to damage.14 |

|

Smoking |

Unclear, although reduced tendon healing capacity has been proposed.15 |

|

Trauma |

Typically damage to rotator cuff tendons from falls or traction injuries. |

Clinical features

History

The primary symptom is shoulder pain.

Typical characteristics of SIS pain include:

- Gradual in onset, but progressive (unless post-traumatic)

- Localised over deltoid region

- Worse during overhead activity, such as combing hair, or during the throwing motion in athletes

- Worse at night

- Improves with rest

- May radiate down the upper arm

True shoulder weakness is typically not present in SIS unless the patient has progressed to having a significant rotator cuff tear. However, significant pain may cause symptoms similar to weakness.

Stiffness is also typically not present unless the patient has progressed to rotator cuff tendinopathy and fibrosis. However, movements may be limited by pain.

Clinical examination

All patients with shoulder pain require a thorough examination of the shoulder.

Typical clinical findings of SIS on shoulder examination include:

- Normal strength: although pain can simulate weakness on examination

- No restriction on passive movement (active abduction may be pain-limited)

- Pain on palpation of subacromial space may suggest subacromial bursitis

Special tests

There are many special tests to assess shoulder pain. No single test can exclude or confirm the diagnosis.

However, there are four tests that are good indicators of the presence of subacromial impingement (Table 2).

Table 2. An overview of special tests for subacromial impingement.

| Test | Process |

|

Neer’s impingement test |

Pain on passive flexion of the shoulder beyond 90o Subsequently relieved on infiltration of local anaesthetic into subacromial space |

|

Hawkin’s impingement test |

Pain on passive internal rotation and flexion to 90o |

|

‘Painful arc’ test |

Pain on abduction between 60o and 120o Reduced pain reported outside the arc (at <60o and >120o) |

|

Jobe’s test |

Pain on resisted flexion of a pronated arm (thumb pointing to the floor) Indicative of supraspinatus pathology |

Differential diagnoses

Table 3. An overview of differential diagnoses to consider and differentiating characteristics from SIS.

| Condition | Differentiating from SIS |

|

Adhesive capsulitis |

Similar to SIS, this may present with gradual-onset shoulder symptoms and may be painful However, marked limitation on both active and passive movement is typical of adhesive capsulitis |

|

Acromioclavicular arthritis |

As seen in SIS, this may present with gradual-onset shoulder pain, and pain on palpation of the ACJ could be mistaken for subacromial pain Impingement tests (including local anaesthetic infiltration) are often negative in ACJ arthritis |

|

Glenohumeral arthritis* |

This may also present with gradual-onset shoulder pain However, limitation on both active and passive movement is more typical of glenohumeral arthritis |

|

Rotator cuff tear* |

Rotator cuff tears may also feature pain on impingement testing; pain on palpation of the subacromial space; and the shoulder pain may be acute or gradual onset, depending on the cause of cuff tear Weakness on resisted abduction and/or external rotation of shoulder suggests a rotator cuff pathology |

|

Glenoid labrum injury |

These injuries may feature a clicking or popping sensation in the shoulder, and pain on palpation of the glenohumeral joint line Neither of these is typical of SIS |

|

Acromioclavicular joint dislocation |

Pain on ACJ palpation could be mistaken for subacromial pain seen in SIS. However, this is typically acute onset pain following trauma, and a ‘step’ deformity of the ACJ may be present. Neither of these is typical of SIS. |

|

Biceps tendon rupture* |

Unlike SIS, this may present with acute onset pain, pain on elbow flexion, and may have a visible deformity of the biceps on examination. |

*These can be long-term sequelae from SIS, but can also present independently, and so should be differentiated from SIS where possible.

Investigations

The diagnosis of SIS is usually made from the clinical examination. The diagnostic sensitivity of clinical examination in the diagnosis of SIS is up to 90%.3

However, diagnostic imaging may be considered to exclude alternative diagnoses.9,18

Imaging

Relevant imaging investigations include:

- Ultrasound: can be used diagnostically at the bedside to detect superficial tendon damage and established bursitis. Ultrasound can also assess any rotator cuff tears.

- X-ray (anteroposterior and lateral views): useful to assess for arthritis of the glenohumeral or acromioclavicular joints.

- MRI: expensive, but excellent at imaging the soft tissue structures of the shoulder.

Indications for MRI imaging

MRI imaging may be considered in the following scenarios:

- If the diagnosis remains unclear after clinical examination and ultrasound scan.

- If a rotator cuff deficit is suspected.

- If conservative management options have been exhausted and symptoms have recurred.

Management

SIS is typically managed conservatively in the first instance. Debate exists surrounding the role of surgery in SIS management, but it is typically reserved for patients with symptoms refractory to conservative measures.3,11

Conservative management

Conservative management of SIS includes:

- Analgesia: NSAIDs

- Physiotherapy

- Corticosteroid injections into the subacromial space

- Activity modification: avoiding overhead activities and excess load-bearing where possible

Surgical management

Surgical management of SIS may include:

- Arthroscopic subacromial decompression

- Bursectomy: often employed alongside decompression in cases with subacromial bursitis

Co-existent rotator cuff tears (sometimes seen in late-stage SIS progression) often require separate surgical management, employing constructs such as suture anchors to unite the torn muscle ends.

Complications

The complications of SIS can be avoided with prompt diagnosis and management. However, complications may include:

- Progression to rotator cuff tears

- Rotator cuff arthropathy: a pattern of glenohumeral arthritis secondary to rotator cuff degeneration

- Adhesive capsulitis

Key points

- SIS refers to a spectrum of pathology associated with the compression of and damage to the rotator cuff tendons as they pass through the subacromial space.

- Extrinsic compression of rotator cuff tendons is typically due to glenohumeral instability, repetitive above-shoulder compression, or osteophytic change of the ACJ joint, or acromion shape.

- Intrinsic degeneration of the rotator cuff tendons is typically due to ageing, smoking, or direct trauma.

- Typical features in the history of SIS relate to gradual onset pain that is worse at night and improves with rest. Weakness and stiffness are less common unless SIS has already progressed to rotator cuff tears.

- On examination of the shoulder, specific tests (including the ‘painful arc’ test, Neer’s test with diagnostic injection, the Hawkins test, and Jobe’s test) are often useful.

- Shoulder ultrasound is useful for visualising tendon injury and bursitis.

- MRI is reserved for cases refractory to conservative treatment, or where the diagnosis is uncertain, or if a rotator cuff deficit is suspected.

- Conservative measures (rest, activity modification, physiotherapy, analgesia and corticosteroid injections) are employed in the first instance.

- Arthroscopic subacromial decompression is the surgical technique most used.

- If untreated, SIS can progress to rotator cuff tears, rotator cuff arthropathy, or adhesive capsulitis.

Reviewer

Katie Hughes

ST1 Trauma & Orthopaedics

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Luime JJ, Koes BW, Hendriksen IJ, et al. Prevalence and incidence of shoulder pain in the general population; a systematic review. Scand J Rheumatol. 2004;33:73-81.

- Juel NG, Natvig B. Shoulder diagnoses in secondary care, a one-year cohort. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:89.

- Garving C, Jakob S, Bauer I, Nadjar R, Brunner UH. Impingement Syndrome of the Shoulder. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114:765-776.

- Anatomography. BodyParts3D, The Database Center for Life Science. License: [CC-BY-SA]

- Petterson SC, Green AM, Plancher KD. Subacromial Space. In: Bain GI, Itoi E, Di Giacomo G, Sugaya H, eds. Normal and Pathological Anatomy of the Shoulder. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2015:141-154.

- Gumina S. Subacromial Space and Rotator Cuff Anatomy. In: Gumina S, ed. Rotator Cuff Tear: Pathogenesis, Evaluation and Treatment. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017:25-44.

- OpenStax. The Glenohumeral Joint. License: [CC-BY]

- Umer M, Qadir I, Azam M. Subacromial impingement syndrome. Orthop Rev (Pavia). 2012;4:e18.

- Simons S, Kruse D, Dixon J. Shoulder Impingement Syndrome. In: Fields K, Grayzel J, eds2020.

- Consigliere P, Haddo O, Levy O, Sforza G. Subacromial impingement syndrome: management challenges. Orthop Res Rev. 2018;10:83-91.

- Creech JA, Silver S. Shoulder Impingement Syndrome. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Copyright © 2020, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2020.

- Neer CS, 2nd. Impingement lesions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983:70-77.

- Koester MC, George MS, Kuhn JE. Shoulder impingement syndrome. The American Journal of Medicine. 2005;118:452-455.

- Spargoli G. Supraspinatus tendon pathomechanics: a current concepts review. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2018;13:1083-1094.

- Lundgreen K, Lian OB, Scott A, Nassab P, Fearon A, Engebretsen L. Rotator cuff tear degeneration and cell apoptosis in smokers versus nonsmokers. Arthroscopy. 2014;30:936-941.

- Phillips N. Tests for diagnosing subacromial impingement syndrome and rotator cuff disease. Shoulder Elbow. 2014;6:215-221.

- Steffes M, Keener J. Subacromial Impingement. 2019.

- Simons S, Kruse D. Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy. In: Fields K, Grayzel J, eds. UpToDate. Vol 20202018.