- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Although rare, anaesthetic emergencies can be life-threatening and require immediate management. This article will cover specific anaesthetic-related emergencies, including laryngospasm, malignant hyperthermia, anaphylaxis and local anaesthetic toxicity.

The general principles for managing an anaesthetic emergency include recognising the signs and symptoms, calling for early help, and delivering appropriate treatment.

Laryngospasm

Laryngospasm is the complete or partial reflex adduction of the vocal cords due to the involuntary contraction of the intrinsic muscle of the larynx. This may cause a variable degree of upper airway obstruction. Closure of the glottic opening is a primitive protective airway reflex to prevent aspiration.

Risk factors

A combination of anaesthetic, patient and surgical-related factors may increase the risk of laryngospasm.

Anaesthetic-related factors include:

- Insufficient depth of anaesthesia

- Mucous or blood in the peri-glottic area

- Airway manipulation (laryngoscopy, suction)

Patient-related factors include:

- Age (young children at greatest risk)

- Airway hyperactivity (asthma, smokers)

- Recent upper respiratory tract infection (up to 6 weeks prior)

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

Surgical-related factors include:

- Upper airway surgery (tonsillectomy)

- Thyroid surgery (superior laryngeal nerve injury)

Clinical features

Typical signs of laryngospasm include:

- Stridor

- Abnormal see-saw movements of the abdominal and chest wall in a spontaneously breathing patient

Management

Initial management of laryngospasm includes:

- Removal of the stimulus (e.g. removal of blood clots by suctioning, removal of supraglottic airway device)

- Calling for senior anaesthetic help

- 100% FiO2, high-flow oxygen using a face mask

- Application of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP)

- Deepening of anaesthesia with propofol

If the above measures do not work, patients will require suxamethonium (a depolarising muscle relaxant) to relax the vocal cords and endotracheal intubation. Caution should be taken on extubation as laryngospasm may recur.

Complications

Complications of laryngospasm include:

- Desaturations and hypoxia

- Negative pressure pulmonary oedema

- Bradycardia (in children)

Malignant hyperthermia

Malignant hyperthermia is an autosomal dominant disorder affecting the skeletal muscles.

A genetic mutation affects the ryanodine receptor of the sarcoplasmic reticulum in skeletal muscles. This results in raised intracellular calcium ions leading to prolonged muscle contraction. The incidence of malignant hyperthermia is reported to be around 2 per 100,000 per year.

Volatile anaesthetic agents (e.g. sevoflurane, isoflurane) and suxamethonium can trigger malignant hyperthermia. The mechanisms by which anaesthetic agents interact with the abnormal receptors are not fully understood but involve impaired magnesium inhibition of sarcoplasmic calcium release.

Clinical features

Typical signs of malignant hyperthermia include:

- Masseter spasm

- Generalised prolonged muscle rigidity

- Increasing end-tidal CO2 (EtCO2)

- A rapid increase in core body temperature

- Rhabdomyolysis leading to acute renal failure

- Hyperkalaemia, which may lead to arrhythmias

Management

Initial management of malignant hyperthermia includes:

- Calling for senior anaesthetic help

- Disconnecting the patient from the anaesthetic machine to stop the delivery of the volatile agent

- Supplying 100% FiO2 from an alternative oxygen source with hyperventilation to reduce CO2

- Maintaining anaesthesia with total intravenous anaesthesia using propofol infusion

- Dantrolene: acts as an antagonist to the ryanodine receptor to block calcium transport into the cells

- Active cooling to reduce body temperature (e.g. ice packs in axilla and groin, infusion of cold saline and abdominal lavage with cold saline by surgeons if the abdominal cavity is open)

- Monitoring of urine output: aim to maintain at 2ml/kg/hr

If hyperkalaemia develops, initial treatment is with insulin/dextrose or sodium bicarbonate as appropriate. Patients will require critical care team input for post-operative monitoring.

Complications

Complications of malignant hyperthermia include:

- Hyperkalaemia

- Acute renal failure

- Life-threatening arrhythmias

Anaphylaxis

Anaphylaxis is an acute, life-threatening type 1 hypersensitivity reaction involving the activation of IgE-bound mast cells and basophils on exposure to a previously sensitised antigen.

Common triggers in the field of anaesthetics are antibiotics, muscle relaxants and latex.

Clinical features

Clinical features of anaphylaxis include:

- Mucocutaneous manifestations: urticaria, generalised rash, lip and tongue swelling, flushing

- Hypotension

- Tachycardia

- Bronchospasm

- Wheezing

Management

Initial management of anaphylaxis includes:

- Stop the administration of the suspected causative drug

- Call for help

- Apply 100% FiO2 oxygen (consider intubation if necessary)

- Administer 0.5ml of 1: 10,000 adrenaline IV, or if there is no peripheral access 0.5 ml of 1:1,000 adrenaline IM. Repeat the dose every 3-5 minutes as necessary.

- Intravenous fluid resuscitation with crystalloids 10-20ml/kg boluses to maintain mean arterial pressure

Nebulised salbutamol or intravenous salbutamol infusion can be used for bronchospasm. Patients may require critical care team input for post-operative monitoring.

For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to the acute management of anaphylaxis.

Local anaesthetic toxicity

Local anaesthetic toxicity is a life-threatening event that may occur after administering local anaesthetic (LA) agents leading to cardiorespiratory and central nervous system instability.

Accidental intravascular injection of local anaesthetic is a common cause of toxicity. However, comorbidities such as liver, cardiac and renal disease may reduce LA clearance, leading to accumulation in the body.

The site of LA injection is also important as certain sites have an increased risk of rapid systemic absorption and toxicity due to the injection being in a highly vascularised area.

The likelihood of local anaesthetic toxicity occurring, arranged in descending order, is as follows: intercostal block, caudal injection, epidural injection, brachial plexus injection, and subcutaneous injection.

The maximum doses of common local anaesthetics used are as follows:

- Lidocaine without adrenaline: 3mg/kg

- Lidocaine with 1:100,000 adrenaline: 7mg/kg

- Bupivacaine: 2mg/kg

- Prilocaine: 6mg/kg

For more information, see our OSCE guide to the infiltration of local anaesthetic.

Clinical features

Clinical features of local anaesthetic toxicity include:

- Sudden onset of altered mental status, tonic-clonic seizures, agitation or coma

- Cardiac arrest

- Tachyarrhythmias or bradyarrhythmias

- Perioral tingling and numbness

Management

Initial management of local anaesthetic toxicity includes:

- Stop injecting the local anaesthetic

- Call for help

- Maintain airway (consider intubation if necessary)

- Supply 100% oxygen and ensure adequate lung ventilation (aim for hyperventilation to raise pH because of metabolic acidosis)

- Seizures: can be treated with benzodiazepines (e.g. lorazepam) or small boluses of propofol or thiopentone appropriate to the patient’s weight

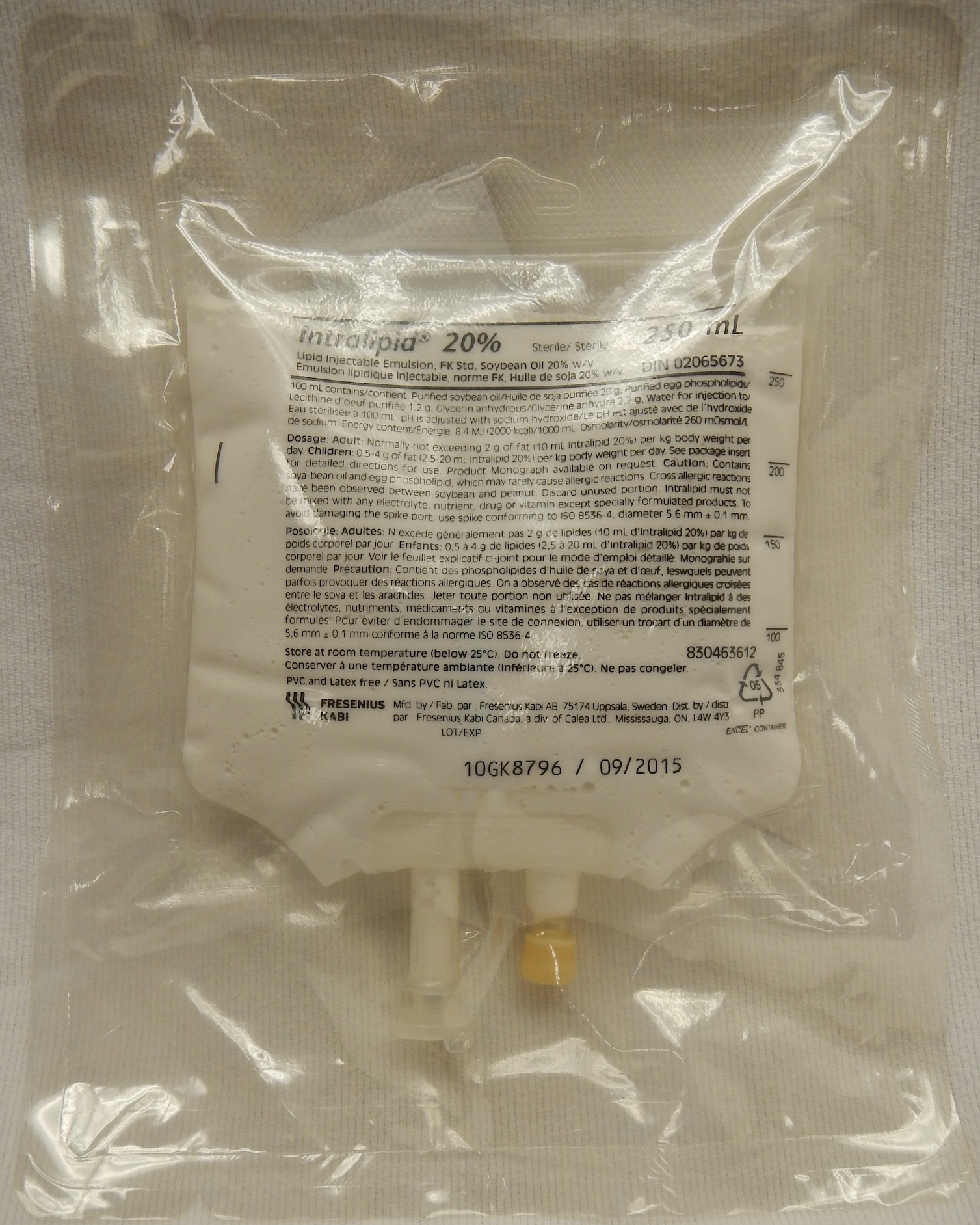

- Start lipid emulsion therapy. A bolus dose of 1.5ml/kg of intralipid 20% should be given in 1 minute. After bolus injection, start intralipid 20% infusion at 15ml/kg/hr. The bolus can be repeated up to 3 times until cardiovascular stability is achieved.

- Transfer to intensive care for ongoing cardiac monitoring

If cardiac arrest occurs, standard treatment with CPR and ALS should be commenced alongside lipid emulsion therapy. Patients may be refractory to treatment, and prolonged resuscitation may be necessary until the local anaesthetic wears off.

Key points

- Important anaesthetic emergencies to be aware of include laryngospasm, malignant hyperthermia, anaphylaxis and local anaesthetic toxicity.

- Call for early senior support in all anaesthetic emergencies

- Use a structured ABCDE approach, and initiate specific treatment for the emergency.

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

Text references

- Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Quick Reference Handbook of Anaesthetic Emergency. Published in April 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- Oxford Handbook of Anaesthesia 3rd Edition Emergencies in Anaesthesia. Published in July 2011.

Image references

- Figure 1. James Heilman, MD. A lipid emulsion (Intralipid) 20%. License: [CC BY-SA]