- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Oxygen is one of the most commonly prescribed drugs in hospitals. Oxygen prescribing is a core task for any doctor, and it is an important part of the UK Medical Licensing Assessment curriculum.1

This article will cover when and how to prescribe oxygen in adults, and highlight some potential dangers of over-oxygenation.

Indication

Oxygen is indicated for hypoxaemia, not breathlessness.

Aim for oxygen saturations of 94-98%, or 88-92% in those at risk of type 2 respiratory failure. The British Thoracic Society (BTS) recommends clinical assessment if the oxygen saturation falls ≥3% below the patient’s target.2

Treating the underlying cause

Supplemental oxygen does not treat the underlying cause of hypoxaemia.

If oxygen needs to be prescribed, you should also take a systematic approach to identify why the patient has desaturated. Always involve a senior clinician if you are concerned or unsure how to manage the patient.

Types of oxygen delivery devices

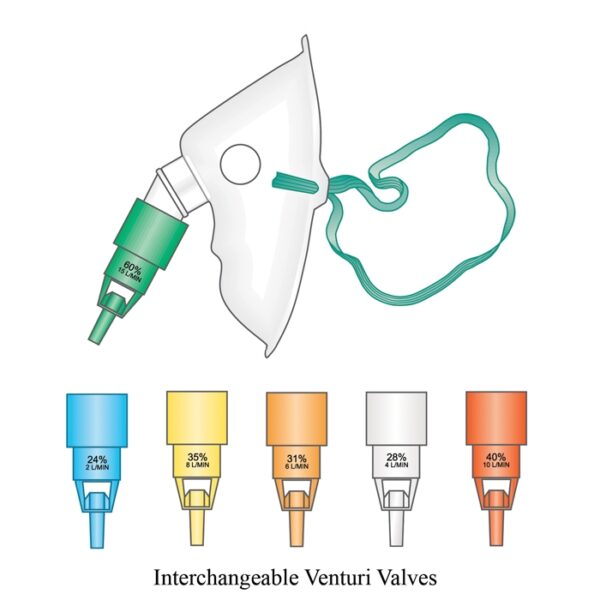

There are various oxygen delivery devices used in clinical practice.

Oxygen is delivered at flow rates measured in L/min.

For every increase in 1L/min, the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) increases by 4% (e.g. 1L/min = 24% FiO2, 2L/min = 28% FiO2 etc).

Table 1. The uses of each main oxygen delivery device.3,4,5

Prescribing oxygen

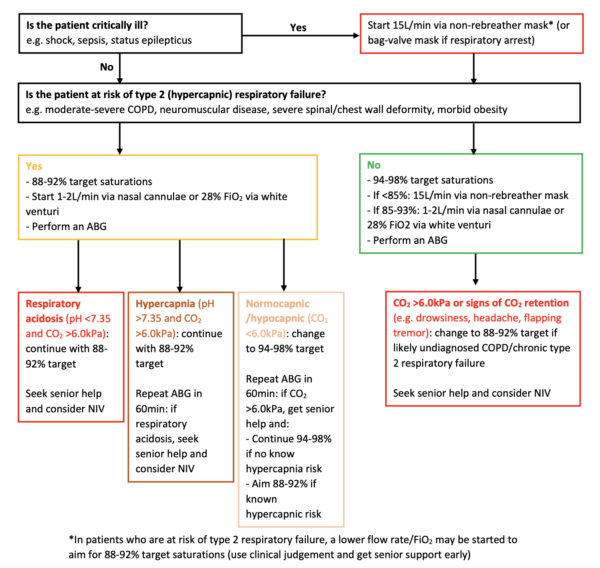

Use an ABCDE approach. If the patient is not breathing, call for help and commence resuscitation. This would involve inserting airway adjuncts and applying high-flow oxygen (15L/min) via bag-valve-mask ventilation.

If the patient is breathing, you should assess how unwell they are.

Critically unwell patients

If the patient is critically unwell and not at risk of type 2 respiratory failure (or you are unsure about their risk), initially prescribe high-flow oxygen (15L/min) through a non-rebreather mask.

If the patient is at risk of type 2 respiratory failure (e.g. COPD patients who are known to be CO2 retainers), it may be safer to start at a lower FiO2 using a Venturi mask and up-titrate if required. Aim for oxygen saturations of 88-92%.

This is due to the risks of type 2 respiratory failure in these patients if you over-oxygenate them. Use clinical judgement and seek senior support early in these cases

Non-critically unwell patients

If the patient is not critically unwell, prescribe oxygen based on Figure 5.

Aim for 100% oxygen saturations in patients with pneumothorax as this reportedly increases the resolution speed.6

Oxygen prescriptions

Since oxygen is a drug, it must be prescribed on a drug chart (paper or electronic). Most drug charts have a section for oxygen prescribing.

Usually, the prescriber would need to specify the target oxygen saturations, oxygen delivery device and desired flow rate/FiO2.

As with any drug, if oxygen can be stopped, then the prescription on the drug chart should be crossed off (or discontinued on electronic prescribing platforms).

Monitoring oxygen saturations

In the UK, oxygen saturations are part of the patient’s basic observations (vital signs) which make up their National Early Warning Score (NEWS).7

The frequency of observations depends on how high the NEWS is (the higher the score, the more frequently it is measured).

Usually, nursing staff follow a local protocol regarding how frequently to measure observations, including oxygen saturations. Document clear instructions if you wish for it to be measured at a certain frequency.

In addition, give clear instructions to nursing staff for escalation if a patient’s oxygen saturations drop below a certain level (e.g. <92%).

For a patient who has just been initiated on oxygen/acutely unwell patients, it is advisable to monitor oxygen at least hourly until they stabilise (e.g. are within their target saturations for 4-6 hours consecutively).

P/F ratio

Use the P/F ratio to check if the patient’s pO2 responds adequately to the supplemental oxygen.

P/F ratio = PaO2 on ABG (“P”) divided by FiO2 (“F”)

The FiO2 must be expressed as a decimal (e.g. 40% FiO2 = 0.4).

The normal P/F ratio is 55kPa or 400mmHg (depending on whether PaO2 is measured in kPa or mmHg).

Calculate the P/F ratio instead of the old-fashioned way of calculating an adequate PaO2 for a patient on supplemental oxygen (subtracting 10 from the FiO2).

Increasing oxygen

If a patient’s oxygen saturations do not reach their target within 3-5 minutes of administering oxygen, the flow rate/FiO2 (if using a Venturi mask) should be increased.2

If the patient becomes critically unwell, increase to 15L/min via a non-rebreather mask

If the patient is not critically unwell, consider increasing oxygen by increments (e.g. from 3L via nasal cannulae to a white Venturi mask – FiO2 28% at 4L/min)

If a patient’s oxygen requirements increase so much that they do not respond to 15L/min via a non-rebreather mask:

- Re-assess the patient (ABCDE assessment)

- Inform a senior clinician if you have not done so already

- Consider the patient’s ceiling-of-care/escalation status. If they are for full escalation, they may need high-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO)/continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)/non-invasive ventilation (NIV)/intubation and ventilation. This is a complex decision based on various factors, including the patient’s ABG results (summarised below and covered in detail here)

Options for escalation

- High-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO): compared to a non-rebreather mask, can deliver oxygen at a greater FiO2 (up to 100%) and flow rate (up to 60L/min). Usually only available in high-dependency/intensive care environments.

- Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP): used in type 1 respiratory failure (PaO2 <8.0kPa), for example cardiogenic pulmonary oedema

- Non-invasive ventilation (NIV): used in type 2 respiratory failure (PaO2 <8.0kPa AND PaCO2 >6.0kPa), for example a COPD exacerbation

Weaning and discontinuing oxygen

Wean down the flow rate/FiO2 if the patient’s oxygen saturations are at least at the higher end of their target saturations for 4-6 hours consecutively.

Wean by small increments (e.g. from a yellow Venturi/35% FiO2 to a white Venturi/28% FiO2). This is usually performed by nursing staff, but ensure you document clear instructions.

Once the patient is stable on 1-2L/min via nasal cannulae, you can cease oxygen completely.

Monitor the patient’s oxygen saturations for 5 minutes without supplemental oxygen. If they remain within their target saturations, measure their oxygen saturations in 1 hour (and then use clinical judgment regarding when you will measure them again).2

Harms of over-oxygenation

Some studies have shown that over-oxygenating a patient (aiming for saturations 96-100%) is associated with an increased risk of death in acute illnesses.8

There are multiple possible explanations for the harms of over-oxygenation:

- Increased reactive oxygen species, leading to cellular damage or death.9

- Systemic vasoconstriction (including cerebral vasoconstriction), leading to organ hypoperfusion.10

- False reassurance: respiratory deteriorations may be detected later if a patient is left on high-flow oxygen (as it would require a more significant deterioration to desaturate on high-flow oxygen compared to lower-flow oxygen).11

Regularly review a patient’s oxygen requirement to ascertain if it can be weaned down.

Feedback

Please click here to fill out the feedback form, which should take less than 1 minute of your time. Feedback is vital as it allows authors to improve their articles, leading to even better content by Geeky Medics!

Reviewer

Dr Neeraj Shah

Specialist registrar in Respiratory Medicine (ST6)

Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- General Medical Council. Practical skills and procedures. Published in 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- O’Driscoll BR et al. BTS guideline for oxygen use in adults in healthcare and emergency settings. Thorax. Published in 2017. Available from: [LINK]

- Heilman J. Nasal prongs. License: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Heilman J. A simple face mask. License: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Heilman J. A non rebreather. License: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Currie GP et al. Pneumothorax: an update. Postgraduate Medical Journal. Published in 2007. Available from: [LINK]

- Royal College of Physicians. National Early Warning Score (NEWS) 2: Standardising the assessment of acute-illness severity in the NHS. Published in 2017. Available from: [LINK]

- Chu DK et al. Mortality and morbidity in acutely ill adults treated with liberal versus conservative oxygen therapy (IOTA): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. Published in 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- Nakane M. Biological effects of the oxygen molecule in critically ill patients. Journal of Intensive Care. Published in 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- Iscoe S et al. Supplementary oxygen for nonhypoxaemic patients: O2 much of a good thing? Critical Care. Published in 2011. Available from: [LINK]

- Kane B et al. Emergency oxygen therapy: from guideline to implementation. Breathe. Published in 2013. Available from: [LINK]