- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

A fistula is an abnormal connection between two epithelial surfaces. In this case, the two surfaces are the anorectal lining and the perianal skin. These fistulas usually develop from an infected anal crypt and often present acutely with an acute perianal abscess.

Their prevalence is 1.8 in 10000 patients, of which 25% are associated with Crohn’s disease.1

Aetiology

The most common cause is sepsis arising from an anal gland that forces its way out to the perianal skin. This is often referred to as the cryptoglandular theory of fistula-in-ano.

A fistula often presents as an acute perianal abscess requiring surgical management, but the underlying fistula is not necessarily obvious at the time.

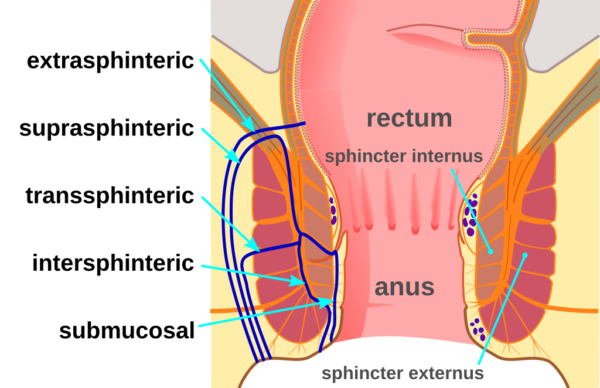

The classification of anal fistulas relates to the tissues they pass through.

Risk factors

Crohn’s disease is the predominant risk factor for fistula formation and is associated with 25% of fistulas in the UK.1

Other risk factors include:3,4

- Previous abscess

- Diabetes

- Hidradenitis supportiva

- High BMI

- Smoking

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Diverticulitis

- Anal trauma

- Anal surgery

- Anal/rectal radiotherapy

- Systemic infections: TB, HIV etc.

Clinical features

Patients can present acutely or with more chronic symptoms

History

When presenting acutely with an abscess, patients complain of rapid onset perianal pain and swelling. This can be with or without systemic manifestations of fevers and tachycardia.

Suspicions should be raised of an underlying fistula with recurrent acute episodes or a chronic history of low-grade infections with seropurulent discharge from an external opening.5

Examination

On examination, erythema and swelling in the perianal area is usually obvious in cases of perianal abscess. External openings may be visible, as well as the presence of pus passing PR. In the acute phase, it is unlikely that the patient will tolerate a digital rectal exam.

For chronic fistulas, the external opening(s) may be visible, and upon digital rectal exam, the fibrous fistula tract may be palpable.

Describing findings on rectal examination

The location of lumps or openings should be described using the clock face.

If you imagine the patient lying on their back with their legs up in stirrups (lithotomy position), then 12 o’clock is directly up from the anus towards the genitalia. It is important to note that usually when examining non-anesthetised patients, they will most likely be lying in the left lateral position, which means the clock face will be rotated.

Goodsall’s rule can be used to predict the tract direction of fistulas. It states that for fistulas with an anterior (9 o’clock to 3 o’clock) external opening, the tract will take a straight course to the internal opening. For fistulas with a posterior (3 o’clock to 9 o’clock) external opening, the trajectory of the fistula tract will curve towards the midline.

A full set of bedside observations should be taken to identify systemic signs such as pyrexia, tachycardia and hypotension.

Differential diagnoses

In the acute episode, it may be impossible to differentiate a perianal abscess with or without an underlying fistula.

Anal fissures may also present with perianal pain but look like tears in the mucosa rather than having discrete openings. These tend to be extremely painful during defecation but are not associated with significant discharge.

Thrombosed external haemorrhoids can also present with a painful perianal lump and can be difficult to distinguish from a small perianal abscess. Often, they are associated with a previous history of painless bleeding post-defecation.

Investigations

Clinical history and examination can often identify fistulas, especially when associated with a perianal abscess.

Examination under anaesthetic (EUA) allows full examination of the area and is often combined with proceeding to treatment of the fistula (or associated abscess).

MRI (rectum) scans can be used to assess for the presence of a fistula and also delineate its tract. This information is used to plan treatment.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis can be made by identifying a fistula tract during examination (with or without anaesthetic) or using MRI.

Management

Medical

For small perianal abscesses, a course of oral antibiotics can be tried.

There is no medical treatment for underlying fistulas, but antibiotics can control the symptoms of low-grade tract infection.

For patients with Crohn’s disease, optimising medical treatment (with input from gastroenterology) will reduce symptoms and further fistula formation.

Surgical

Acute

For patients presenting with a perianal abscess that doesn’t respond to oral antibiotics, is too large for a trial of antibiotics, is systemically unwell, or is immunosuppressed, incision and drainage are the preferred treatments.

The patient should be consented for “Examination Under Anaesthetic (EUA) Rectum, Incision and Drainage of Abscess +/- Proceed to treatment of fistula” appropriately assessed and prepared by the anaesthetic and nursing teams. The patient should be positioned in the ‘legs up’ Lithotomy position, prepped and draped.

Initially, the surgeon should examine and assess the perianal area, including a rectal exam and potentially a rigid sigmoidoscope and/or an Eisenhammer rectal speculum. They are looking for the extent of the abscess, the location of any internal and external openings of a fistula and what tissues they appear to cross.

An incision should be made over the fluctuant area, and the abscess cavity should be drained, explored and washed out. Packing can be used for haemostasis, but regular long-term packing is no longer routinely recommended.6

Potential fistula tracts should not be probed for during drainage of an acute perianal abscess as they are likely to self-resolve if this is the first episode.6 If there is a large obvious fistula tract, then in some practices, it would be acceptable to place a Seton, which is a length of material that keeps the tract open and allows drainage of infection.

Chronic

Once sepsis has been drained and if symptoms persist, then more formal surgical treatment for the underlying fistula can begin.

This highly depends on the surgeon, but the initial standard approach is outlined below. All surgical management seeks to balance risks of fistula recurrence and damage to sphincter muscle that can leave patients with bowel continence problems. The risk of sphincter damage is particularly important in female patients as they have anatomically less muscle and are at higher risk of bowel continence problems. The risks and benefits must be discussed with the patient before any treatment commences.

Once the internal and external openings have been identified, a Seton is often placed to keep the tract open and identify the tissue it involves. A Seton is a length of material of either a non-absorbable suture or smooth silastic vascular sling which passes down the tract and then has its ends tied together to create a loop. This Seton will prevent recurrent sepsis and can be left long-term, as the treatment ceiling in some cases.

For ‘low’ fistula involving minimal or no sphincter muscle then the tract can be laid open and granulation tissue curetted to allow spontaneous healing, this is called a fistulotomy.

For ‘high’ fistulas involving muscle, several surgical options are available. The most common is the ‘cutting Seton’ technique. This is when a braided non-absorbable Seton is placed (as described above) but is tied tight to allow it to slowly cut through the tissues. Depending on the size of the fistula, this may require regular (weekly) operations to replace the Seton and retighten it as it cuts through.

Other treatments for high fistulas include advancement flaps, ligation of intersphicteric fistula tract (LIFT Procedure), endoscopic ablation, laser surgery, fibrin glue or bioprosthetic plugs. The approach depends on the fistula tract and the preference of the specialist surgeon.

Complications

Recurrent abscesses are more likely in patients with a maturing underlying fistula tract.

2.8% of patients presenting with an acute perianal abscess will go on to be diagnosed with Crohn’s disease.6 When multiple fistula tracts form (often in patients with Crohn’s disease), this is particularly complex to manage as the risks to bowel continence from multiple procedures escalate.

Key points

- An anal fistula is an abnormal connection between the anorectal lining and the perianal skin

- Usually develop from an infected anal crypt and often present acutely with an acute perianal abscess

- Clinical history and examination are usually enough to diagnose a fistula, but an MRI scan and EUA can be used as adjuncts to delineate the fistula tract

- Initial treatment should be with antibiotics for small abscesses, but for larger abscesses and/or unwell patients will require an incision and drainage of the abscess

- If chronic fistula tract is present then a seton is usually inserted to provide drainage of infection and better delineate the tract

- Treatment is guided by the amount of sphincter muscle that is involved in the fistula tract as damage to this can cause bowel continence problems

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Hokkanen SR, Boxall N, Khalid JM, Bennett D, Patel H. Prevalence of anal fistula in the United Kingdom. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7(14):1795-804.

- McortNGHH. Fistula diagram. License: [CC BY-SA]

- Wang D, Yang G, Qiu J, Song Y, Wang L, Gao J, et al. Risk factors for anal fistula: a case-control study. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18(7):635-9.

- NHS. Anal Fistula. Available from: [LINK]

- McLatchie G, Borley N, Chikwe J. Fistula in ano. Oxford Handbook of Clinical Surgery: Oxford University Press; 2013. p. 410-1.

- Miller AS, Boyce K, Box B, Clarke MD, Duff SE, Foley NM, et al. The Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland consensus guidelines in emergency colorectal surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2021;23(2):476-547.