- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Aphasia is an acquired language impairment and communication disability.

The term is primarily used to describe issues with language production and comprehension caused by focal brain lesions (e.g. stroke, brain tumour), but is also used to describe language difficulties caused by diffuse brain damage (e.g. acquired brain injury, primary progressive aphasia), and transient impairment of language function during migraines or seizures.1

The clinical presentation of aphasia varies significantly between people, impacting the understanding and expression of spoken language, reading, and writing. Aphasia does not affect intelligence.

Over 350,000 people in the UK have aphasia,2 and up to 40% of people experience aphasia after a stroke.3

Aphasia vs dysphasia

Whilst the terms ‘aphasia’ and ‘dysphasia’ are often used interchangeably, consistent use of the term aphasia is preferred to reduce confusion for both patients and professionals.4

Aetiology

Language systems

Language does not refer merely to our speech but to complex cognitive processes through which meaning and information are conveyed – “the ability to communicate through common symbols”.5

Knowing how the brain’s language systems are impacted in aphasia can help us anticipate these patients’ communication needs.

In aphasia, we talk about ‘receptive’ and ‘expressive’ language, referring to systems of receiving and decoding meaning from sensory input (language comprehension) and finding and formulating language, respectively (language production).

For most people, language activity occurs in the dominant left hemisphere, and diseases of the left hemisphere cause the ‘classical’ aphasia syndromes.

The non-dominant right hemisphere is understood to have some contribution to language processing, such as in decoding abstract language. It may also have a role in the recovery of language function in aphasia following a stroke.5

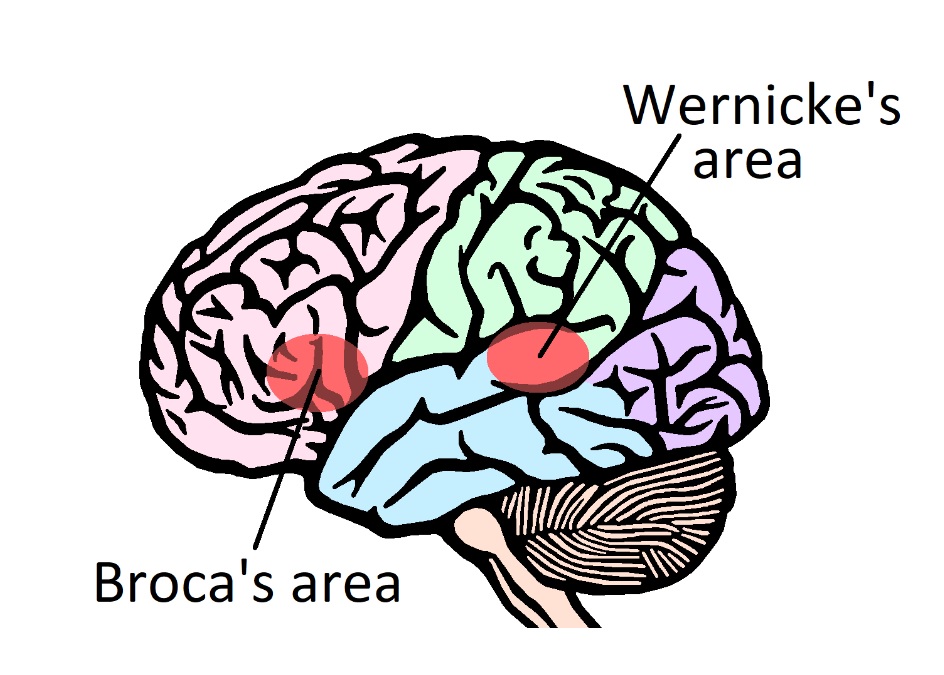

Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area

Traditional models of language neuroanatomy assume that:5

- Expressive language function is organised around Broca’s area (an area of the inferior frontal cortex supplied by the superior division of the middle cerebral artery)

- Receptive language function is organised around Wernicke’s area (located at the posterior superior temporal cortex supplied by the inferior division of the middle cerebral artery)

- These two areas are connected by fibres of the arcuate fasciculus

The Boston classification is a common system of ordering aphasia presentations according to vascular syndromes of the dominant hemisphere. It includes the diagnoses of Broca’s (expressive) and Wernicke’s (receptive) aphasia as well as conduction aphasia (an impairment of word repetition only, theoretically caused by a lesion of the arcuate fasciculus).6

Broca’s aphasia

In Broca’s aphasia, the person might experience difficulties with ‘word finding’ in spoken and written language, commonly with nouns. They may compensate with circumlocutory speech. For example, paraphrasing or describing an item rather than using its proper noun (e.g. ‘ the thing for cutting things’ instead of ‘scissors’). Their speech may seem halting, with some common grammatical words left out.

Some words may be replaced with words which relate to or resemble what the speaker intended to say – which are called paraphasic errors. For example, someone saying ‘table’ instead of ‘chair’ because of their semantic relation, or the phonemic error ‘blandet’ for ‘blanket’.

People with frontal lobe lesions, most commonly involving Broca’s area, may also experience difficulty understanding complex sentences, which may reflect the role of this cortical region in working memory and other core language activities.5

Wernicke’s aphasia

In Wernicke’s aphasia a person classically experiences issues with language comprehension, which others might mistake for a hearing or memory impairment.

Despite this, their speech may retain a fluent quality, with the grammar and syntax of ordinary speech relatively preserved. Again, semantic and phonemic paraphasic errors and neologisms (or new, spontaneously created words) may be present, with the meaningful content of speech often lost.5

In clinical practice, it is common for a patient with aphasia to experience both expressive and receptive communication issues. Therefore, an individual approach with assessment by a speech and language therapist is required to profile the needs of each patient and evaluate the impact on daily activity and social participation.6

A comprehensive assessment of all components and modalities of language should be supported by a wider MDT assessment of cognition and function, as underlying cognitive issues may be masked by aphasia.

Causes of aphasia

Stroke is the leading cause of aphasia. Other causes include acquired brain injury, space-occupying lesions, central nervous system infections, neurodegenerative disorders such as primary progressive aphasia, and autoimmune conditions such as multiple sclerosis.

Transient aphasia may be seen during a migraine with aura or seizure or without an underlying structural cause, such as in functional neurological disorder (FND).8

Differential diagnoses

There are several other acquired communication disorders which may co-present or present similarly to aphasia:

- Dysarthria: a motor speech disorder affecting the articulation of speech sounds and generally causing reduced speech intelligibility. It may involve changes to respiration, phonation, articulation, resonance, and prosody.

- Apraxia of speech: apraxias are disorders of skilled sequential muscle activation. Apraxia of speech describes a motor speech disorder involving impaired planning and programming of speech movements. It often features inconsistent errors and visible articulatory groping (difficulty positioning the lips, tongue, and jaw to produce the desired speech sounds) and rarely occurs independently of aphasia.9

- Cognitive communication disorders: difficulties with communication resulting from cognitive impairment (e.g. attention and memory issues).

- Auditory agnosia: impaired verbal word recognition despite normal sensory input. Written comprehension may be preserved, differentiating it clinically from receptive aphasia.5

The inability to produce any audible speech could be caused by motor speech disorders or laryngeal dysfunction. In such cases, assessment of writing or typing may be helpful to determine the presence of a language impairment.

Management

Communication

Use supportive communication strategies to enable patients with aphasia to participate in healthcare-related decisions and access medical treatment.10

For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to communicating with patients with aphasia.

Ensure written information is accessible for people with aphasia.11,12

Speech and language therapy

Patients with aphasia should be referred to speech and language therapy services. Their input may include:11,13

- Impairment-based therapy focuses on improving language abilities

- Exploring compensatory strategies or Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) to improve functional communication abilities

- Focusing on participation across areas of life that are important to that person (e.g. work, relationships, hobbies)

- Providing information and training about aphasia to conversation partners

- Providing a space for people with aphasia to express their feelings and experiences (individual sessions or aphasia groups)

- Supporting people with aphasia to demonstrate their capacity to make decisions

- Supporting people with aphasia towards long-term self-management, this is sometimes achieved by working with independent or charitable organisations

Psychological support

Regardless of the cause, developing aphasia is a traumatic experience which can have far-reaching impacts on an individual’s emotional well-being and quality of life. After one year, the majority of people with post-stroke aphasia experience depression.14 Therefore, assessment of mood and provision of psychological support is recommended.11

Psychological screens or assessments that rely on comprehension and/or expression of spoken language may not be accessible for some people with aphasia. The assessment process should be adapted to the individual’s specific communication abilities.11 There may be instances when seeking the views of others is necessary. However, all efforts should be made to support people with aphasia in expressing their feelings and experiences.

Some tools for assessing mood in severe aphasia include the D-VAMS (digital visual analogue mood scale), a patient-completed visual tool, and the SADQ10, an observer-completed screening tool.15

Recovery in aphasia

In post-stroke aphasia, the pace of recovery is generally greatest during the first weeks and months.

Further recovery in language function may continue for several years. During this time, an individual’s communication impairment profile can change. For example, from a global aphasia (where expressive and receptive language is severely impaired) to a predominantly expressive impairment.5 However, for many patients, aphasia is a lifelong communication disability.

Complications

Complications of aphasia include:11,14,16

- Increased likelihood of experiencing adverse events in hospital and exclusion from discussion and decision-making about their healthcare

- Increased risk of low mood and depression in post-stroke aphasia and difficulty accessing mental health treatment

- Loss of employment, negative relationship changes, and social isolation

Key points

- For many patients, aphasia is a lifelong communication disability.

- It can impact language expression and comprehension across modalities of spoken, written and symbolic communication.

- Stroke is the leading cause of aphasia; however, there are many other disease processes which must be considered in the differential diagnosis of an acquired communication disorder.

- Neuroanatomical models and classification systems can help us understand aphasia but most patients do not fit neatly into categories- receptive and expressive features may be present, and there may be comorbid motor speech difficulties. Individualised assessment and intervention by a Speech and Language Therapist is recommended.

- Aphasia can have a significant detrimental impact on psychological well-being, participation in healthcare and wider social function.

- Healthcare workers must adapt their communication approach to facilitate better participation and shared decision making for people with aphasia.

Reviewer

Sandra Hewitt

Clinical Lead Speech and Language Therapist for Stroke Services

NHS Highland

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Berg, K., Isaksen, J., Wallace, S.J., Cruice, M., Simmons-Mackie, N. and Worrall, L., 2022. Establishing consensus on a definition of aphasia: an e-Delphi study of international aphasia researchers. Aphasiology, 36(4), pp.385-400.

- Stroke association [internet]. Aphasia Awareness. Available from: [LINK]

- Mitchell, C., Gittins, M., Tyson, S., Vail, A., Conroy, P., Paley, L. and Bowen, A., 2021. Prevalence of aphasia and dysarthria among inpatient stroke survivors: describing the population, therapy provision and outcomes on discharge. Aphasiology, 35(7), pp.950-960.

- Worrall, L., Simmons-Mackie, N., Wallace, S.J., Rose, T., Brady, M.C., Kong, A.P.H., Murray, L. and Hallowell, B., 2016. Let’s call it “aphasia”: Rationales for eliminating the term “dysphasia”. International Journal of Stroke, 11(8), pp.848-851.

- Kirshner, H.S., Wilson, S.M. Aphasia and Aphasic syndromes. In: Jankovic et al (eds). Bradleys neurology in clinical practice. 8th ed. P.133-148. Elsevier, 2022.

- Sheppard, S.M. and Sebastian, R., 2021. Diagnosing and managing post-stroke aphasia. Expert review of neurotherapeutics, 21(2), pp.221-234.

- Tremblay, P. and Dick, A.S., 2016. Broca and Wernicke are dead, or moving past the classic model of language neurobiology. Brain and language, 162, pp.60-71.

- BMJ best practice. Assessment of aphasia. Published in 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- Hybbinette, H., Schalling, E., Plantin, J., Nygren-Deboussard, C., Schütz, M., Östberg, P. and Lindberg, P.G., 2021. Recovery of apraxia of speech and aphasia in patients with hand motor impairment after stroke. Frontiers in Neurology, 12, p.634065.

- Burns, M., Baylor, C., Dudgeon, B.J., Starks, H. and Yorkston, K., 2015. Asking the stakeholders: Perspectives of individuals with aphasia, their family members, and physicians regarding communication in medical interactions. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 24(3), pp.341-357.

- National Clinical Guideline for Stroke for the UK and Ireland. London: Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party; 2023 May 4. Available from: [LINK]

- Stroke association. Accessible information guidelines. Published in 2012. Available from: [LINK]

- Jayes, M., Palmer, R. and Enderby, P., 2021. Giving voice to people with communication disabilities during mental capacity assessments. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 56(1), pp.90-101.

- Baker, C., Worrall, L., Rose, M. and Ryan, B., 2020. ‘It was really dark’: the experiences and preferences of people with aphasia to manage mood changes and depression. Aphasiology, 34(1), pp.19-46.

- Laures-Gore, J.S., Farina, M., Moore, E. and Russell, S., 2017. Stress and depression scales in aphasia: relation between the aphasia depression rating scale, stroke aphasia depression questionnaire-10, and the perceived stress scale. Topics in stroke rehabilitation, 24(2), pp.114-118.

- Manning, M., MacFarlane, A., Hickey, A. and Franklin, S., 2019. Perspectives of people with aphasia post-stroke towards personal recovery and living successfully: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. PLoS One, 14(3), p.e0214200.