- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is the most common cause of abnormal discharge in women of reproductive age.1

Though the exact aetiology is unknown, the broad pathophysiology is that BV is caused by a loss of the normal flora which inhabits the vaginal canal with a simultaneous increase in anaerobic bacteria. This leads to a rise in pH and alterations in the consistency, composition and odour of vaginal discharge.2

Up to 84% of patients are asymptomatic and many individuals are unwilling to seek medical advice due to perceived stigma and embarrassment surrounding vaginal health.

One study in the United States demonstrated that around 29.2% of the general female population of reproductive age had BV at any one time, with only 15.7% being symptomatic.3,4

Aetiology

Pathophysiology

Typically, the vagina has an acidic pH of less than 4.5. This is an ideal environment for lactobacilli to thrive (Figure 1).

Occasionally, environmental factors can trigger a pH rise in the vaginal canal. When the pH is elevated above 4.5, the environment becomes too hostile for lactobacilli to survive.

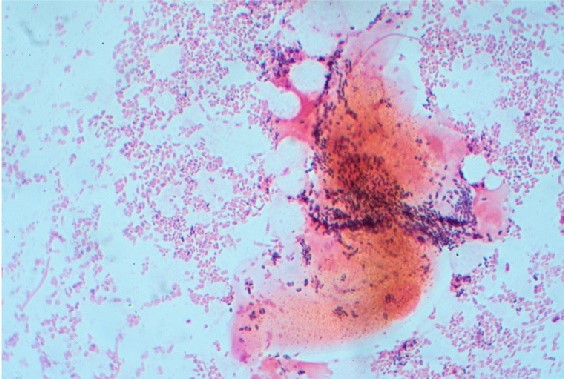

Once the normal flora of the vagina has decreased, irregular bacteria such as Gardnerella vaginalis, Prevotella spp., Mycoplasma hominis and Mobinculus spp. (amongst others) can begin to proliferate (Figure 2). This leads to an altered composition of vaginal discharge, leading to changes in consistency and smell.

Risk factors

Risk factors for BV include:1,3

- Sexual activity: especially unprotected cunnilingus. It is important to note that whilst BV is sexually associated, it is not a sexually transmitted infection

- Existing sexually transmitted infection (STI): such as chlamydia and gonorrhoea

- New sexual partner

- Afro-Caribbean ethnicity

- Vaginal douching: introduction of cleaning solutions into the vagina

- Bubble baths, shower gels and “feminine hygiene” products

- Intrauterine contraceptive device (IUD) “copper coil”. It is not known if the intrauterine contraceptive system (such as the “Mirena”) has the same effect.

Some factors have been shown to be protective for BV, these include:1,3

- Using barrier methods during sexual activity, such as condoms and dams

- Washing genitals externally with water alone

- The combined oral contraceptive pill

Clinical features

History

Most patients with BV are asymptomatic.

If present, typical symptoms of BV may include:

- Larger volumes of vaginal discharge, occasionally requiring a panty liner to control

- Discharge takes on a thin consistency compared to physiological discharge

- Discharge can become white or grey in colour

- Offensive smelling discharge which is often described as “fishy”

- A mild itching sensation around the vulva and vaginal entrance (less common)

- A cyclical appearance of symptoms which worsen after sexual intercourse, cunnilingus or menstruation

Clinical examination

A thorough female pelvic examination should be conducted for patients with suspected BV.

Typical clinical findings may include:

- A thin white discharge coating the vaginal walls or the speculum

- Offensive smell to discharge

- An alkali pH if a litmus test is used

Patients are unlikely to be tender on bimanual examination.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnoses to consider include:

- Candida (thrush)

- Sexually transmitted infections (STIs): chlamydia, gonorrhoea, herpes simplex virus (HSV), trichomoniasis vaginalis (TV)

- Physiological discharge

- Pregnancy

- Atrophic vaginitis: the most likely cause of discharge changes in post-menopausal women due to a reduction in oestrogen leading to localised irritation

- Chemical irritants: these lead to allergic vaginitis; make sure to ask about changes in body wash, laundry detergents, lubricants and use of sex toys

- Foreign body: most commonly tampons, but also consider other objects which could have been used during sexual intercourse or contaminants if following a sexual assault

- Post gynaecological surgery

- Cervical ectropion: a physiological change associated with younger women and use of the contraceptive pill

- Tumour (vulva, vagina, cervix or endometrium): this can be benign or malignant and will require an urgent gynae-oncology review

Table 1. An overview of the different causes of vaginal discharge

|

|

BV |

Candida |

Trichomoniasis vaginalis |

Physiological |

|

Discharge |

Thin, white-grey |

Thick, white |

Thin, frothy |

Changes throughout menstrual cycle, often clear or white |

|

Odour |

Fishy |

Non-offensive |

Fishy |

Odourless |

|

Vulval irritation |

Usually none but occasional burning and itching |

Vulvovaginitis causing itching, fissures and swelling |

Itching, soreness and dysuria |

Nil |

|

pH |

>4.5 |

<4.5 |

>5 |

<4.5 |

Investigations

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations for BV include:

- High vaginal swabs: for microscopy and STI screening (NAAT)

- pH assessment of discharge with litmus paper: not routinely done in a UK clinic setting but used in Europe and in low resource settings

The diagnosis of BV can be made based on bedside investigations using the Amsel criteria and the Hay/Ison criteria.

Amsel criteria

Using the Amsel criteria, any three out of the four criteria must be met to make a diagnosis of BV:6

- Homogeneous discharge on clinical examination

- Microscopy showing vaginal epithelial cells coated with many bacilli (“clue cells”)

- Vaginal pH >4.5: assessed with litmus paper

- Fishy odour on adding 10% potassium hydroxide to vaginal fluid

Hay/Ison Criteria

The Hay/Ison criteria take into account the microscopic appearance of gram-stained vaginal smear. These criteria are recommended by the British Association of Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH).1

The appearance of vaginal flora may be graded as follows:

- Grade 1 (normal): lactobacillus morphotypes predominate

- Grade 2 (intermediate): mixed flora with some Lactobacilli present, but Gardnerella or Mobiluncus morphotypes also present

- Grade 3 (BV): predominantly Gardnerella and/or Mobiluncus morphotypes. Few or absent lactobacilli

- Grade 4: gram-positive bacteria predominate

Management

Conservative management

Asymptomatic individuals who are not pregnant, do not routinely require treatment as BV is usually self-limiting and resolves after 3-7 days.

General advice for patients should include:

- Avoid vaginal douching

- Avoid bubble baths, shower gel and antiseptic products near the genitals

- Some patients find probiotics useful. This can be in the form of dietary intake (kimchi, kefir, kombucha etc), tablet or vaginal pessary. Research suggests this can be useful, though there is no conclusive evidence yet.7

Medical management

Medical treatment is recommended for certain groups of individuals with BV. This includes anyone with symptoms and any pregnant individuals, regardless of choice in continuation of pregnancy.

All the following treatments are believed to be similarly efficacious with oral metronidazole being 87-92% successful at four weeks and vaginal metronidazole at 61-94%.8

Antibiotic options

Options for treating BV include:

- Oral metronidazole 400-500 mg BD for 5-7 days

- Oral metronidazole 2 g stat

- Oral tinidazole 2 g stat

- Oral clindamycin 300 mg BD for seven days

- Metronidazole vaginal gel 0.75% OD for five days

- Clindamycin vaginal gel 2% OD for seven days

The treatment of choice for BV is usually oral metronidazole BD. Low-dose metronidazole is safe for use in pregnancy. However, high dose metronidazole (2g stat) should be avoided in pregnancy.

Individuals who are breastfeeding should be offered vaginal preparations. When prescribing vaginal preparations, it is important to warn patients that the ingredients may degrade condoms, therefore extra precautions should be taken to avoid unwanted pregnancy or STIs.

Complications

BV places patients at higher risk of acquiring and transmitting STIs, including chlamydia, gonorrhoea and HIV.2

Although there is a high prevalence of BV infection in women with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), data does not suggest that BV is causative of PID.9

In pregnancy, BV is associated with first-trimester miscarriage (77%), late miscarriage (after 12 weeks – 23%), preterm labour (12.5%), low birth weight and postpartum endometritis.12,13

Key points

- BV is the most common cause of abnormal vaginal discharge in women of reproductive age.

- BV is caused by an overgrowth of anaerobic vaginal bacteria, which results in loss of the normal lactobacilli population and an increase in vaginal pH (>4.5).

- Women are often asymptomatic (up to 84%). However, when symptomatic, patients present with a change in discharge (thin, white and offensive smelling).

- Asymptomatic non-pregnant women do not require treatment.

- For symptomatic or pregnant patients, the treatment of choice is 400-500mg metronidazole PO BD for 5-7 days.

- It is important to treat all pregnant women, regardless of whether they are continuing with their pregnancy or having a termination due to the risk of future pregnancy complications.

- BV places patients at higher risk of acquiring and transmitting STIs, including chlamydia, gonorrhoea and HIV.

Reviewer

Dr Frances Lander

Genitourinary Medicine Registrar

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Lazaro, Dr Neil. Sexually Transmitted Infections in Primary Care (2e). s.l. : Royal College of General Practitioners, 2013.

- Bertini, Marco. Bacterial Vaginosis and Sexually Transmitted Diseases: Relationship and Management. 2017.

- The Prevalence of Bacterial Vaginosis in the United States, 2001–2004; Associations With Symptoms, Sexual Behaviors, and Reproductive Health. Koumans, Emilia et al. 11, s.l. : Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 2007, Vol. 34.

- Attitudes and experience of women to common vaginal infections. Johnson, Sarah. et al. 4, s.l. : Journal of lower genital tract infections, 2010, Vol. 14.

- Willacy, Hayley. Bacterial Vaginosis. 2020. Available from: [LINK].

- Diagnostic Value of Amsel’s Clinical Criteria for Diagnosis of Bacterial Vaginosis. Mohammadzadeh, Farnaz,. et al. 3, s.l. : Global Journal of Health Science, 2015, Vol. 7.

- Probiotics for the treatment of women with bacterial vaginosis. Falagas, M.E. et al. 7, s.l. : Clinical Microbiology and Infection , 2007, Clinical Microbiology and Infection, Vol. 13, pp. 657-664.

- Comparison of oral and vaginal metronidazole for treatment of bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy: impact on fastidious bacteria. Mitchel, Caroline et al. 89, s.l. : BMC Infectious Diseases , 2009, Vol. 9.

- Does Bacterial Vaginosis Cause Pelvic Inflammatory Disease? Taylor, Brandie,. et al. 2, s.l. : Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 2013, Vol. 40.

- Randomised treatment trial of bacterial vaginosis to prevent post-abortion complication. Miller, Leslie. et al. 9, s.l. : British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 2004, Vol. 111.

- Prevention of infection after induced abortion. Achilles, Sharon. et al. 4, s.l. : Contraception, 2011, Vol. 83.

- Bacterial vaginosis in association with spontaneous abortion and recurrent pregnancy losses. Gözde, Izik. et al. 3, s.l. : Journal of Cytology, 2016, Vol. 33.

- The Role of Bacterial Vaginosis in Preterm Labor. Kirchner, Jeffrey T. 62, s.l. : American Family Physician, 2000, Vol. 1.

Figure 1 and 2. Dr Graham Beards. Normal and BV flora. License: [CC BY-SA]