- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Fundoscopy (ophthalmoscopy) frequently appears in OSCEs and you’ll be expected to pick up the relevant clinical signs using your examination skills. This guide provides a step-by-step approach to performing fundoscopy. It also includes a video demonstration.

Gather equipment

Gather the appropriate equipment:

- Ophthalmoscope

- Mydriatic eye drops

Introduction

Wash your hands and don PPE if appropriate.

Introduce yourself to the patient including your name and role.

Confirm the patient’s name and date of birth.

Briefly explain what the examination will involve using patient-friendly language.

Example explanation

“I will be using a magnifying tool called an ophthalmoscope to look at the back of your eyes with the lights off.”

“To do this, I’ll need to get quite close to your face. I’ll place a hand on your forehead to prevent us from bumping into each other.”

“I’ll also be using some eye drops to dilate your pupils. The dilating drops will cause your vision to be temporarily blurry and you’ll be more sensitive to light, so you’ll not be able to drive for several hours afterwards.”

Gain consent to proceed with the examination.

Position the patient sitting on a chair.

Ask if the patient has any pain before proceeding.

Inspection of the external eye

Inspection of the external eyes including the anterior segment can provide a lot of valuable clinical information.

See our anterior segment examination guide for a more detailed approach.

General inspection

Ask the patient to look straight ahead and inspect both of the eyes assessing the following:

- Peri-orbital regions

- Eyelids

- Eyes (including pupils)

Note any abnormalities such as:

- Swelling

- Redness

- Discharge

- Prominence of the eyes

- Abnormal eyelid position: ptosis can be a sign of Horner’s syndrome (often very subtle ptosis with miosis) and oculomotor nerve palsy (can vary from partial to complete ptosis and usually with a ‘down and out’ eye position and an enlarged pupil)

- Abnormal pupillary shape, size and/or asymmetry

Pupillary assessment

The pupil is the hole in the centre of the iris that allows light to enter the eye and reach the retina.

Inspect the patient’s pupils for abnormalities.

Pupil size

Normal pupil size varies between individuals and depends on lighting conditions (i.e. smaller in bright light, larger in the dark).

Pupils can be smaller in infancy and larger in adolescence, then often smaller again in the elderly.

Pupil symmetry

Note any asymmetry in pupil size (anisocoria). This may be longstanding and physiological or be due to acquired pathology. If the difference in pupil size becomes greater in bright light such as when facing a window in daylight, this would suggest that the larger pupil is the pathological one. This is because the normal pupil will constrict in brighter light accentuating the difference in size. If the difference is more pronounced in dim lighting, this would imply the smaller pupil is abnormal as the larger pupil would then dilate while the pathologically small pupil remains the same size.

Examples of asymmetry include a larger pupil in oculomotor nerve palsy and a smaller one in Horner’s syndrome.

Pupil shape

Pupils should be round. Abnormal shapes can be congenital or due to pathology (e.g. posterior synechiae associated with uveitis) or previous trauma and surgery.

Peaked pupils in the context of trauma are suggestive of globe rupture (the peaked appearance is caused by the iris plugging the leak).

Pupil colour

Asymmetry in pupillary colour is most commonly due to congenital disease.

In rare cases, asymmetry of colour can suggest Horner’s syndrome, with the paler washed-out iris being pathological.

Pathology which may be noted during general inspection

Examples of pathology you may note during general inspection of the eye include:

- Periorbital erythema and swelling: a feature of preseptal cellulitis (anterior to the orbital septum) or orbital cellulitis (posterior to the orbital septum)

- Eyelids: lumps (benign or malignant), oedema, ptosis and entropion/ectropion

- Eyelashes: loss of eyelashes (can be associated with malignant lesions), trichiasis (eye lashes rubbing on the cornea) and blepharitis collarettes

- Pupils: abnormal size, shape, colour and symmetry (see above)

- Conjunctival injection (redness): this can be diffuse, sectorial or limbal. Dilated inflamed blood vessels can be due to infection, allergy, trauma and inflammation.

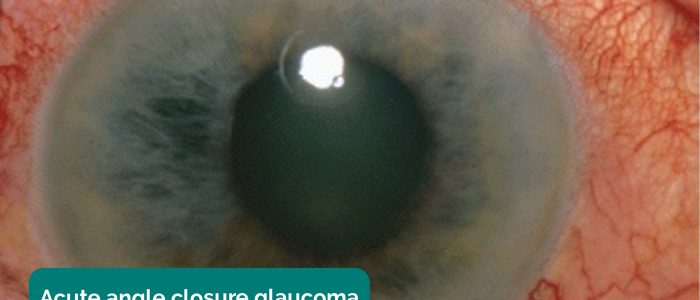

- Cornea: diffuse haziness in acute angle-closure glaucoma or a patch of white infiltrate due to a corneal ulcer. Staining of the cornea with fluorescein suggests epithelial loss. A dendritic pattern is seen with herpes simplex infection.

- Anterior chamber: a fluid level may be noted in hyphaema (blood – red in colour) or a hypopyon (inflammatory cells – yellow in colour).

- Discharge: watery discharge is typically associated with allergic or viral conjunctivitis or reactive physiological production (e.g. corneal abrasion/foreign body). Purulent discharge is more likely to be associated with bacterial conjunctivitis. Very sticky, stringy discharge can suggest chlamydial conjunctivitis while blood staining can be seen with gonococcus.

Causes of red eye

Below is a non-exhaustive list of causes of red eye, with their associated clinical features.

Painless red eye:

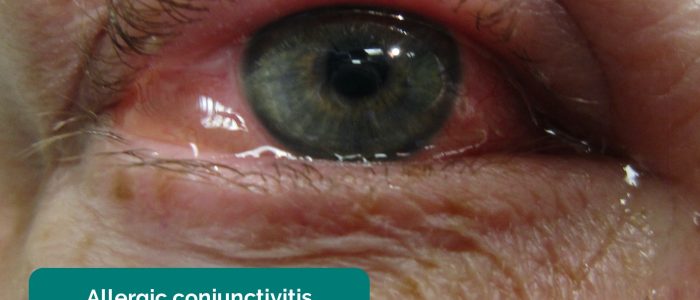

- Conjunctivitis: diffuse conjunctival injection (unilateral or bilateral), discharge, swollen conjunctiva (chemosis) and debris. Bacterial conjunctivitis typically has more purulent discharge than viral or allergic conjunctivitis.

- Subconjunctival haemorrhage: a flat, bright red patch on the conjunctiva with sharply defined borders and normal conjunctiva surrounding it.

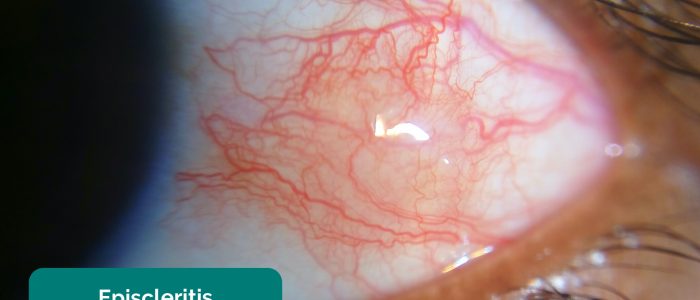

- Episcleritis: sectoral area of subconjunctival injection (unilateral). The subconjunctival injection in episcleritis is superficial and, as a result, moveable with a swab (using topical anaesthesia) pressed gently on the conjunctiva.

- Dry eye: caused by deficiencies in tear production and maintenance secondary to conditions such as blepharitis (obstruction of meibomian glands). Clinical features include diffuse conjunctival injection (unilateral or bilateral), inflamed lid margins with crusting and matted eyelashes.

Painful red eye:

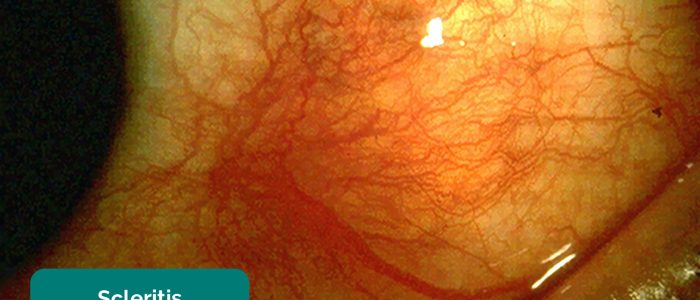

- Scleritis: deep pinkish localised conjunctival injection (unilateral), visual acuity may be reduced, minimal watery discharge, photophobia and a tender globe (causing the patient to wake at night). Symptoms tend to progressively worsen and individuals commonly have other connective tissue diseases.

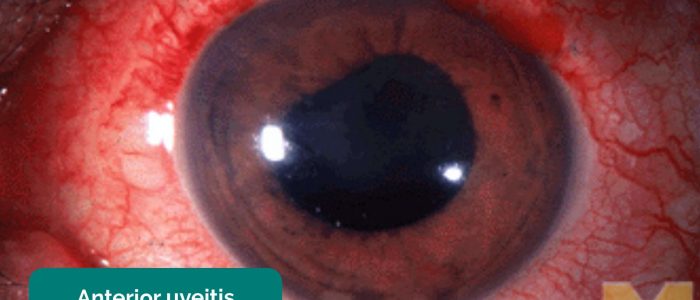

- Uveitis: circumciliary conjunctival injection (unilateral), hazy cornea, distorted pupil, hypopyon, reduced visual acuity, watery discharge, photophobia and pain are common clinical features.

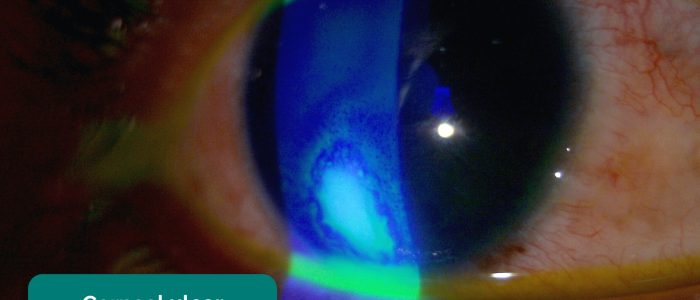

- Corneal abrasion: eye redness, pain, watering and photophobia are common clinical features. Epithelial defects can be very hard to see with the naked eye but stain brightly with fluorescein drops and a cobalt blue light.

- Corneal ulcer: typical clinical features include pain, watering, photophobia and a staining epithelial defect with associated haziness (infiltrates). The epithelial defect may appear fluffy, irregular and apparent even without a slit lamp.

- Acute angle-closure glaucoma (AACG): typical clinical features include significant pain leading to vomiting, circumciliary conjunctival injection (unilateral), reduced visual acuity, photophobia, haloes in vision, hazy cornea and a mid-dilated unreactive pupil.

- Foreign bodies: may be visible on the surface of the eye or embedded within the cornea or sclera. Associated clinical features include redness, pain, watering and a ‘foreign body sensation’. Foreign bodies may be hidden under the top and bottom of the eyelid.

Ophthalmoscope overview

Parts

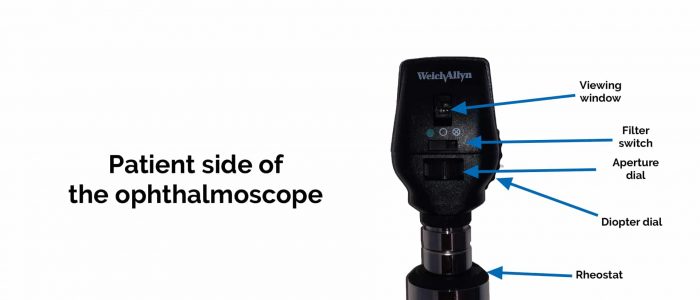

Parts of the ophthalmoscope include:

- Viewing window: this is where you look through to observe the eye

- Filter switch: allows you to select a light filter (e.g. blue cobalt light)

- Aperture dial: adjust the size of the light beam

- Diopter dial: adjusts the lens used to view the eye

- Diopter power display: shows the current lens being used

- Rheostat: adjusts the intensity of the light beam

- On/off switch: turns the device on and off

Aperture size (beam size)

Ophthalmoscopes typically allow you to select from a range of different apertures including:

- Micro aperture: used for viewing the fundus through very small undilated pupils

- Small aperture: used for viewing the fundus through an undilated pupil

- Large aperture: used for viewing the fundus through a dilated pupil and for the general examination of the eye

- Slit aperture: can be helpful in assessing contour abnormalities of the cornea, lens and retina as it makes elevation easier to see

Filter

Filters can be used to highlight specific pathology:

- Cobalt blue filter: used to look for corneal abrasions or ulcers with fluorescein dye (see our anterior segment examination guide for more details)

- Red-free filter: used to look at the centre of the macula and other vasculature in more detail

Preparation for fundoscopy

1. It is essential to darken the room for the examination. Make sure the patient is positioned seated prior to turning out the lights to avoid accidents.

2. Dilate the patient’s pupils using short-acting mydriatic eye drops such as tropicamide 1%. You will be unable to monitor pupil reactions once dilating drops have been applied, furthermore assessing vision, colour vision, double vision and visual fields will be less accurate once drops are instilled.

3. Ask the patient to look straight ahead for the duration of the examination (asking the patient to fixate on a distant target such as a light switch can cause confusion if you then obstruct the view of this target).

Assess the fundal reflex

Correct terminology

The term fundal reflex is preferred over red reflex as the colour of the healthy reflex varies depending on a patient’s skin colour.

In patient’s with lighter skin, the reflex typically appears orange-red in colour, whereas in those with darker skin, the reflex can be yellow-white or even blue in colour.

Ophthalmoscope settings

To set up the ophthalmoscope for assessing the fundal reflex adjust the diopter dial to correct for your refractive error so that you can see the patient and their eye clearly from a distance:

- If you have normal visual acuity, you can set the diopter dial to 0.

- If you have a refractive error but are planning to wear glasses/contact lenses that correct this when using the ophthalmoscope you can also set it to 0.

- If you have a refractive error and are not going to wear your glasses/contact lenses you should adjust the diopter dial to match your prescription (e.g. -2).

How to assess for the fundal reflex

1. Look through the ophthalmoscope, shining the light towards the patient’s eye at a distance of approximately one arm’s length.

2. Observe for a reddish/orange/white/yellow/blue reflection in each pupil, caused by light reflecting back from the vascularised retina.

Causes of an absent fundal reflex

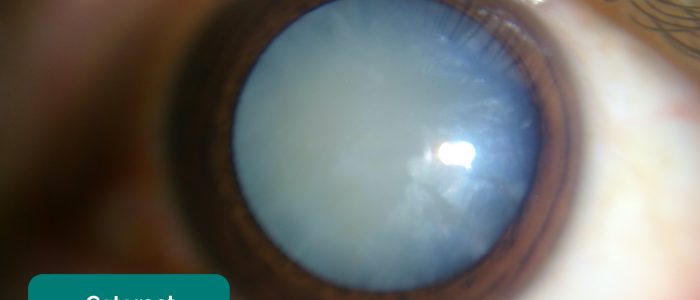

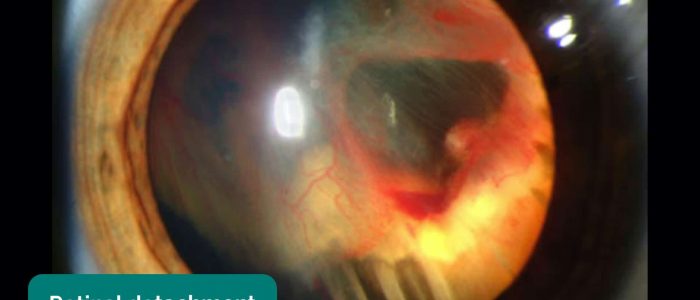

Absence of the fundal reflex in adults is often due to cataracts in the patient’s lens blocking the light. Other causes include vitreous haemorrhage and retinal detachment.

Absence of the fundal reflex in children can be due to congenital cataracts, retinal detachment, vitreous haemorrhage and retinoblastoma.

Assess the fundus

Ophthalmoscope settings

To set up the ophthalmoscope for assessing the fundus, adjust the diopter dial so that it is the net result of yours and the patient’s refractive error:

- If you and the patient have normal visual acuity, set the dial to 0 (e.g. 0 + 0 = 0).

- If you have a refractive error but are planning to wear glasses/contact lenses that correct this, assume you have a refractive error of 0 and add the patient’s refractive error to this (e.g. 0 + -2 = -2).

- If the patient has a refractive error and you have normal visual acuity set the dial to the net refractive error. An example of this would be (your refractive error of 0) + (patient’s refractive error of -2) = a setting of -2.

- If the patient has a refractive error and you have a refractive error set the dial to the net refractive error. An example of this would be (your refractive error of +3) + (patient’s refractive error of -2) = a setting of +1.

- If things appear out of focus during the assessment, simply adjust the diopter dial until things look sharper.

Assess the optic disc

1. If you are assessing the patient’s right eye, you should hold the ophthalmoscope in your right hand and vice versa. Place the hand not holding the ophthalmoscope onto the patient’s forehead to prevent accidental collision between yours and the patient’s face.

2. Approaching from a 10-15 degree angle slightly temporal to the patient, move closer whilst maintaining the fundal reflex.

3. Begin by identifying a blood vessel and then follow the branching of this blood vessel towards the optic disc (the branches point like arrows towards the optic disc).

4. Once you identify the optic disc assess its characteristics including the contour, colour and the cup (“3Cs”):

- Contour: the borders of the optic disc should be clear and well defined. If the borders appear blurred it may suggest the presence of optic disc swelling (papilloedema) secondary to raised intracranial pressure.

- Colour: a healthy optic disc should look like an orange-pink doughnut with a pale centre. The orange-pink colour represents well-perfused neuro-retinal tissue. A pale optic disc suggests the presence of optic atrophy which can occur as a result of optic neuritis, advanced glaucoma and ischaemic vascular events.

- Cup: the cup is the pale centre of the orange-pink doughnut mentioned previously. The pale colour of the cup is due to the absence of neuroretinal tissue. The vertical size of the cup can be estimated in relation to the optic disc as a whole, known as the “cup-to-disc ratio”. A cup-to-disc ratio of 0.3 (i.e. the cup occupies one-third of the height of the optic disc) is generally considered normal. An increased cup-to-disc ratio suggests a reduced volume of healthy neuro-retinal tissue, which can occur in glaucoma.

Assess the retina

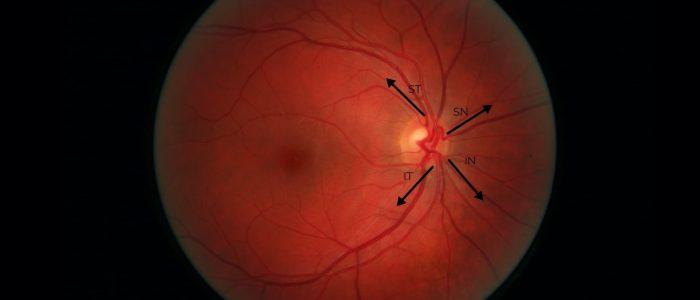

5. Methodically assess each quadrant of the retina and the associated vascular arcades in a clockwise or anticlockwise fashion looking for evidence of pathology:

- Superior temporal (ST)

- Superior nasal (SN)

- Inferior nasal (IN)

- Inferior temporal (IT)

Types of retinal pathology

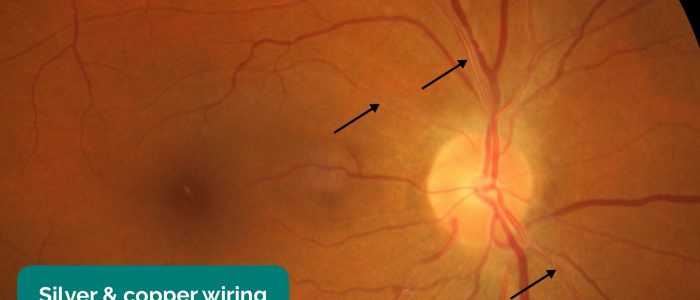

- Arteriolar narrowing: subtle, with generalised arteriolar narrowing with typical copper or silver wire appearance. Most commonly associated with the early stages of hypertensive retinopathy.

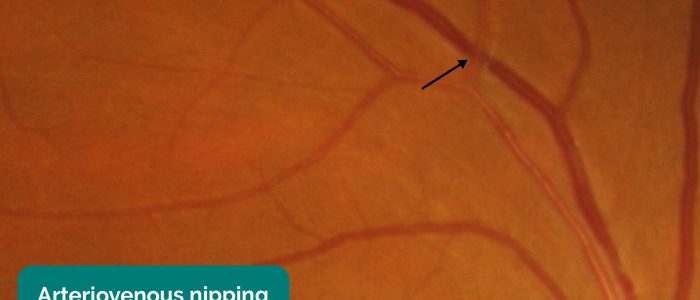

- Arteriovenous nipping/nicking: areas of focal narrowing, and compression of venules at sites of arteriovenous crossing. The typical appearance involves bulging of retinal veins on either side of the area where the retinal artery is crossing. Most commonly associated with grade 2 hypertensive retinopathy.

- Dot and blot haemorrhages: arise from bleeding capillaries in the middle layers of the retina and may look like microaneurysms if small enough. They are most commonly associated with diabetic retinopathy.

- Flame haemorrhages: larger haemorrhages with a flame-like appearance caused by rupture of pre-capillary arterioles or small veins in the retinal nerve fibre layer. Most commonly associated with grade 3 hypertensive retinopathy, thrombocytopaenia, retinal vein occlusion and trauma.

- Cotton wool spots: appear as small, fluffy, whitish superficial lesions and represent infarcts of the neuro-retinal layer. They are most commonly associated with diabetic retinopathy and grade 3 hypertensive retinopathy.

- Hard exudates: waxy yellow lesions with relatively distinct margins arranged in clumps or rings, often surrounding leaking microaneurysms. They are most commonly associated with diabetic retinopathy and grade 3 hypertensive retinopathy.

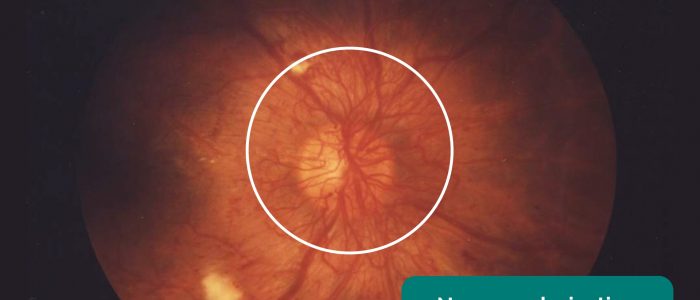

- Neovascularisation: formation of new blood vessels that appear as a net of small curly vessels, with or without associated haemorrhages. They may be located on the optic disc or elsewhere on the retina. They are most commonly associated with advanced proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

- Pan-retinal photocoagulation: the primary treatment for proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Clinically it is seen as clusters of pale burn marks on the retina which have been created by the laser used in the treatment process.

- Branch retinal vein occlusion: blockage of one of the four retinal veins, each of which drains about a quarter of the retina. Typical signs include flame haemorrhages, dot and blot haemorrhages, cotton wool spots, hard exudates, retinal oedema, and dilated tortuous veins.

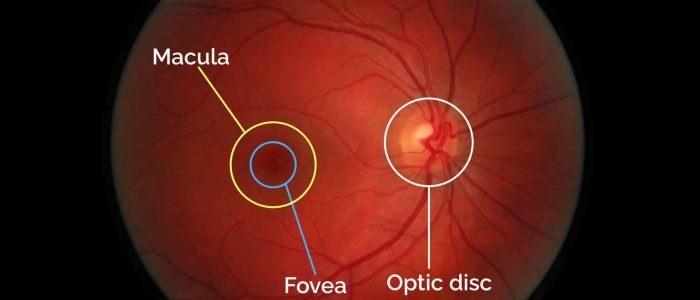

Assess the macula

6. Finally, inspect the macula by asking the patient to briefly look directly into the light of the ophthalmoscope. The macula is found lateral (temporal) to the optic nerve head and is yellow in colour. The central part of the macula, the “fovea” is about the same diameter as the optic disc and appears darker than the rest of the macula due to the presence of an additional pigment.

Types of macula pathology

- Hard exudates: waxy yellow lesions with relatively distinct margins arranged in clumps or rings, often surrounding leaking microaneurysms. They are most commonly associated with diabetic retinopathy, grade 3 hypertensive retinopathy and retinal vein occlusions.

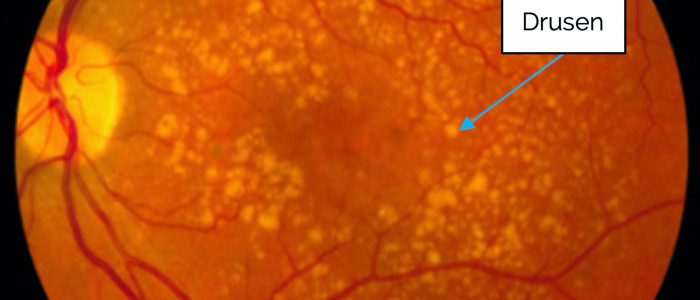

- Drusen: yellow-white flecks scattered around the macular region representing remnants of dead retinal pigment epithelium. Most commonly caused by age-related macular degeneration.

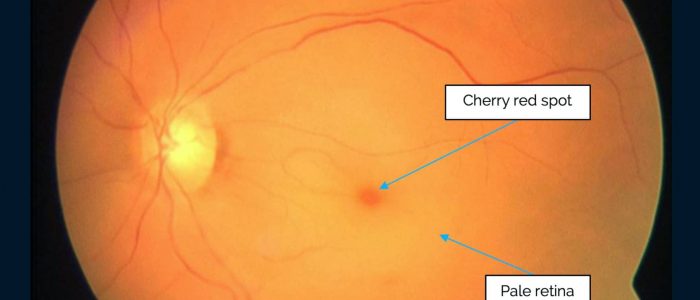

- Cherry-red spot: associated with central retinal artery occlusion which typically presents with sudden profound visual loss.

Assess the other eye

Repeat assessment of the fundal reflex and fundus on the other eye. You will need to approach the patient from the opposite side and hold the ophthalmoscope in your other hand.

Video demonstration: How to visualise the fundus

To complete the examination…

Explain to the patient that the examination is now finished.

Thank the patient for their time.

If mydriatic drops were instilled, remind the patient they cannot drive for the next 3-4 hours until their vision has returned to normal.

Dispose of PPE appropriately and wash your hands.

Summarise your findings.

Further assessment and investigations

All of the following further assessments and investigations are dependent on the patient’s presenting complaint and in most cases, none of them would need to be performed:

- Amsler chart: to assess for central visual loss and distortion which is commonly associated with macular degeneration.

- Cranial nerve examination: to further assess for evidence of cranial nerve pathology (e.g oculomotor nerve).

- Blood pressure: if there are concerns about hypertensive retinopathy.

- Capillary blood glucose: if there are concerns about diabetic retinopathy.

- Retinal photography: to better visualise any abnormalities noted on fundoscopy.

References

- James Heilman, MD. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Allergic conjunctivitis. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Adapted by Geeky Medics. Bacterial conjunctivitis. Licence: Public domain.

- FiP. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Subconjunctival haemorrhage. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Imrankabirhossain. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Episcleritis. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Kribz. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Scleritis. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Adapted by Geeky Medics. Blepharitis. Licence: Public domain.

- Jonathan Trobe, M.D. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Anterior uveitis. Licence: CC BY.

- Jonathan Trobe, M.D. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Acute angle-closure glaucoma. Licence: CC BY.

- EyeMD (Rakesh Ahuja, M.D.). Adapted by Geeky Medics. Hypopyon. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Tripp on Flickr. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Pre-septal cellulitis. Licence: CC BY 2.0.

- Waster. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Miosis. Licence: CC BY.

- Evan Herk. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Foreign body. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- James Heilman, MD. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Corneal abrasion. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Yoanmb. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Corneal ulcer. Licence: CC BY SA.

- Jonathan Trobe, M.D. Adapted by Geeky Medics. RAPD. Licence: CC BY.

- Adapted by Geeky Medics. Fundal reflex. Licence: Public domain.

- Imrankabirhossain. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Cataract. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Adapted by Geeky Medics. Retinoblastoma. Licence: Public domain.

- Adapted by Geeky Medics. Retinal detachment. Licence: Public domain.

- Yandle on Flickr. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Normal fundus. Licence: CC BY 2.0.

- Jonathan Trobe, M.D. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Papilloedema. Licence: CC BY.

- Frank Wood. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Hypertensive retinal disease. Licence: CC BY.

- Adapted by Geeky Medics. Cotton wool spots. Licence: Public domain.

- National Eye Institute. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Pan-retinal photocoagulation. Licence: Public domain.

- Ku C Yong, Tan A Kah, Yeap T Ghee, Lim C Siang and Mae-Lynn C Bastion. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Licence: CC BY. Retinal branch occlusion.

- National Eye Institute. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Pan-retinal photocoagulation. Licence: Public domain.

- Adapted by Geeky Medics. Drusen. Licence: Public domain.

- National Eye Institute. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Macular oedema. Licence: Public domain.

- Achim Fieß, Ömer Cal, Stephan Kehrein, Sven Halstenberg, Inez Frisch, Ulrich Helmut Steinhorst. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Cherry red spot. Licence: CC BY.