- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

This guide provides a step-by-step approach to assessing the anterior segment of the eyes and includes a video demonstration.

Gather equipment

Gather the appropriate equipment:

- Ophthalmoscope (traditional device or Arclight)

- Fluorescein eye drops

- Cotton bud (for everting the eyelid and manipulating the conjunctiva)

- Local anaesthetic drops if available

Introduction

Wash your hands and don PPE if appropriate.

Introduce yourself to the patient including your name and role.

Confirm the patient’s name and date of birth.

Briefly explain what the examination will involve using patient-friendly language.

Gain consent to proceed with the examination.

Position the patient sitting on a chair.

Ask if the patient has any pain before proceeding.

General inspection

Ask the patient to look straight ahead and inspect both of the eyes assessing the following:

- Peri-orbital regions

- Eyelids

- Eyes (including pupils)

Note any abnormalities such as:

- Swelling

- Redness

- Discharge

- Prominence of the eyes

- Abnormal eyelid position: ptosis can be a sign of Horner’s syndrome (often very subtle ptosis with miosis) and oculomotor nerve palsy (can vary from partial to complete ptosis and usually with a ‘down and out’ eye position and an enlarged pupil)

- Abnormal pupillary shape, size and/or asymmetry

Pupillary assessment

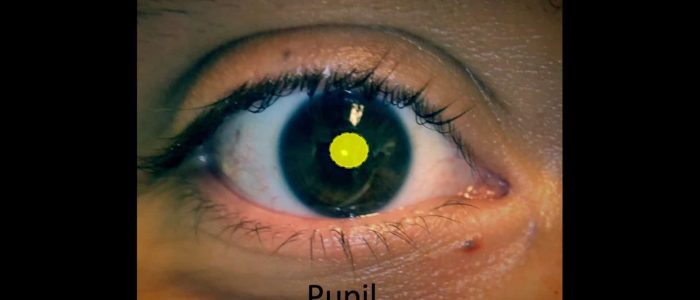

The pupil is the hole in the centre of the iris that allows light to enter the eye and reach the retina.

Inspect the patient’s pupils for abnormalities.

Pupil size

Normal pupil size varies between individuals and depends on lighting conditions (i.e. smaller in bright light, larger in the dark).

Pupils can be smaller in infancy and larger in adolescence, then often smaller again in the elderly.

Pupil symmetry

Note any asymmetry in pupil size (anisocoria). This may be longstanding and physiological or be due to acquired pathology. If the difference in pupil size becomes greater in bright light such as when facing a window in daylight, this would suggest that the larger pupil is the pathological one. This is because the normal pupil will constrict in brighter light accentuating the difference in size. If the difference is more pronounced in dim lighting, this would imply the smaller pupil is abnormal as the larger pupil would then dilate while the pathologically small pupil remains the same size.

Examples of asymmetry include a larger pupil in oculomotor nerve palsy and a smaller one in Horner’s syndrome.

Pupil shape

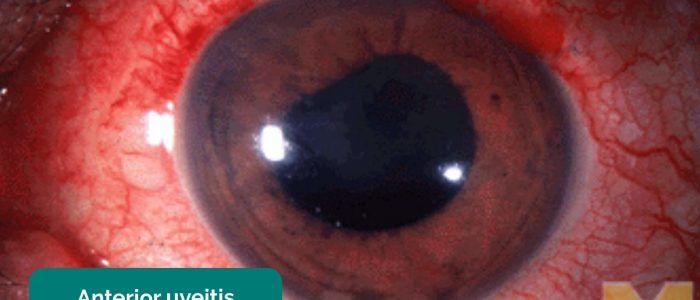

Pupils should be round. Abnormal shapes can be congenital or due to pathology (e.g. posterior synechiae associated with uveitis) or previous trauma and surgery.

Peaked pupils in the context of trauma are suggestive of globe rupture (the peaked appearance is caused by the iris plugging the leak).

Pupil colour

Asymmetry in pupillary colour is most commonly due to congenital disease.

In rare cases, asymmetry of colour can suggest Horner’s syndrome, with the paler washed-out iris being pathological.

Pathology which may be noted during general inspection

Examples of pathology you may note during general inspection of the eye include:

- Periorbital erythema and swelling: a feature of preseptal cellulitis (anterior to the orbital septum) or orbital cellulitis (posterior to the orbital septum)

- Eyelids: lumps (benign or malignant), oedema, ptosis and entropion/ectropion

- Eyelashes: loss of eyelashes (can be associated with malignant lesions), trichiasis (eye lashes rubbing on the cornea) and blepharitis collarettes

- Pupils: abnormal size, shape, colour and symmetry (see above)

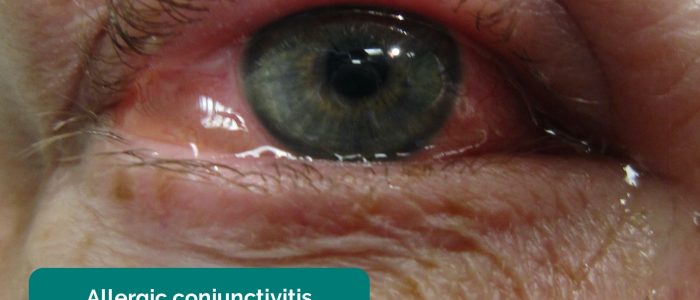

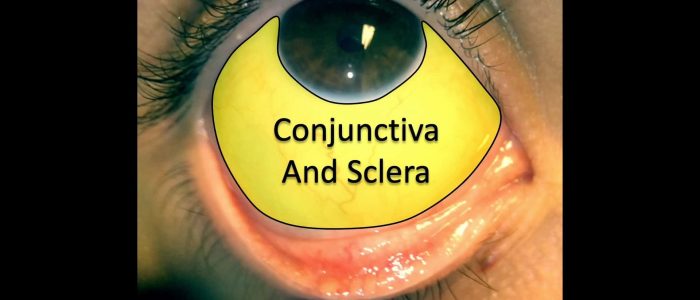

- Conjunctival injection (redness): this can be diffuse, sectorial or limbal. Dilated inflamed blood vessels can be due to infection, allergy, trauma and inflammation.

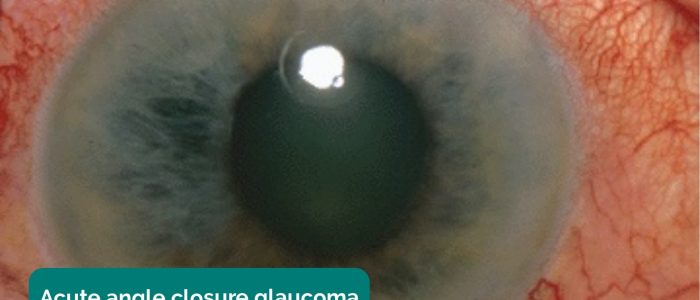

- Cornea: diffuse haziness in acute angle-closure glaucoma or a patch of white infiltrate due to a corneal ulcer. Staining of the cornea with fluorescein suggests epithelial loss. A dendritic pattern is seen with herpes simplex infection.

- Anterior chamber: a fluid level may be noted in hyphaema (blood – red in colour) or a hypopyon (inflammatory cells – yellow in colour).

- Discharge: watery discharge is typically associated with allergic or viral conjunctivitis or reactive physiological production (e.g. corneal abrasion/foreign body). Purulent discharge is more likely to be associated with bacterial conjunctivitis. Very sticky, stringy discharge can suggest chlamydial conjunctivitis while blood staining can be seen with gonococcus.

White light assessment

Ophthalmoscope settings

To set up the ophthalmoscope for assessing the anterior surface of the eye:

- Turn on the white light of the ophthalmoscope

- Adjust the diopter dial to a high green number (e.g. +10 to +20). The ophthalmoscope focal plane is now very short (5 to 10 cms) and will magnify your view.

When using the Arclight, click through until the white light comes on at the loupe end of the device (there is a range of brightness settings – start with the most appropriate for your patient). Children typically only tolerate a dimmer light initially. Increase the brightness if the patient allows.

Assessment using white light

1. Set up your device as described above.

2. Stand to the side of the patient and place your hand on the patient’s forehead to prevent an accidental collision.

3. Carefully approach the right eye with your right eye, until the front of the eye comes into focus. On the ophthalmoscope, this will vary depending on the power of the lens selected. If using the Arclight, the front of the eye will be in focus at 6cms.

4. Ask the patient to look outwards and then inwards. Note the various structures whilst looking for any abnormalities.

5. Ask the patient to look upwards whilst you gently hold their lower eyelid to assess the lower areas of the eye ball and lids.

6. Then ask the patient to look downwards whilst you gently hold their upper eyelid to assess the upper areas.

During the assessment, it can be useful to think about the structures of the anterior eye and possible clinical signs in the following three groups:

- Eyelashes and lid margins (upper and lower)

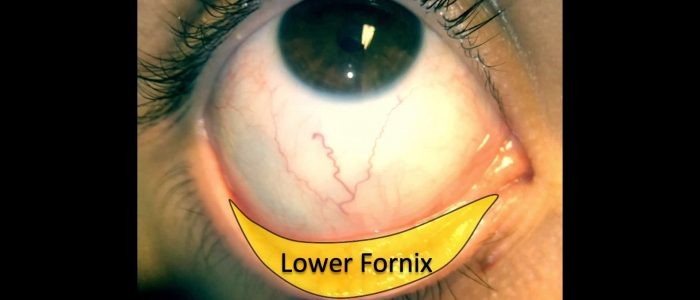

- Conjunctiva, sclera and lower fornix

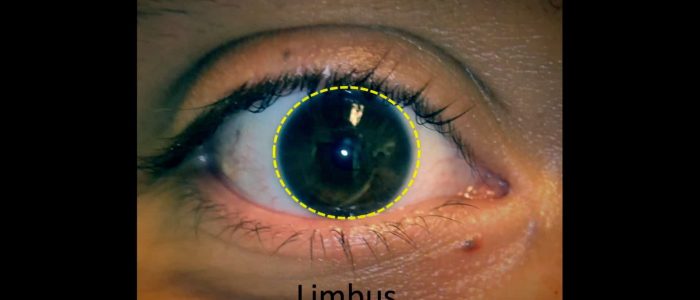

- Cornea, limbus and pupil

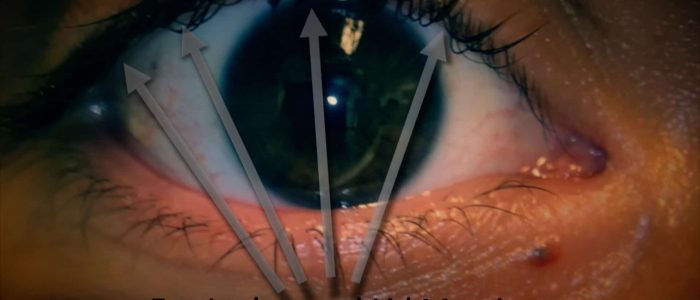

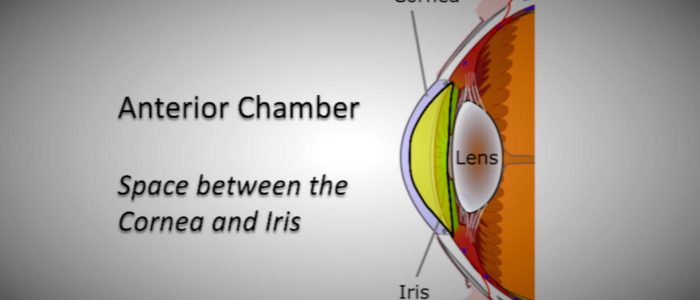

Assessment of anterior chamber depth

7. Assess the depth of the anterior chamber (the space between the cornea and the iris):

- Shine a light from the temporal side of the eye to assess the depth

- A shadow on the nasal iris can suggest a shallow anterior chamber

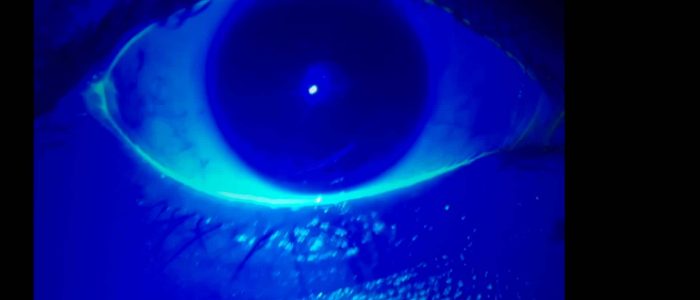

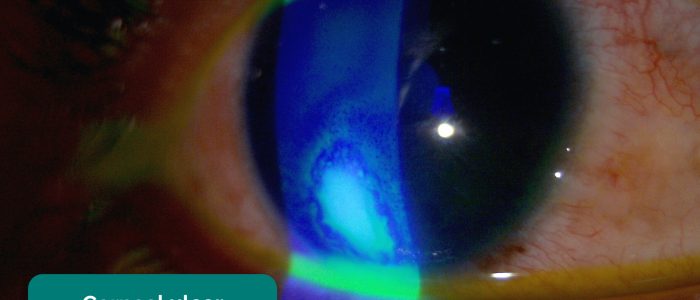

Blue light assessment

1. Add some fluorescein to the lower fornix either with a moistened strip or as a drop.

2. Switch to the blue light on your device. With an ophthalmoscope, this is typically done by rolling a filter wheel at the base of the head. With the Arclight, click the button until it comes on after the white lights.

3. Inspect the surface of the eye with the blue light. The dye will fluoresce highlighting:

- The tear film

- Areas of epithelial loss (e.g. corneal abrasion) and disease (e.g. corneal ulcer)

4. Record the location and size of any epithelial loss/disease.

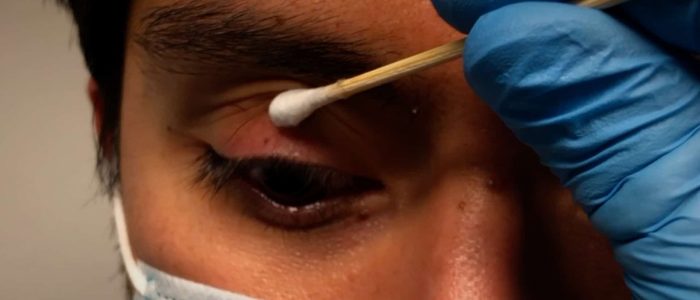

Superior tarsal plate assessment

1. Place a cotton bud on the skin of the upper eyelid.

2. Gently lift the eyelid upwards whilst simultaneously pressing downwards with the cotton bud.

3. Initially observe the superior tarsal plate for any abnormalities with your naked eye then take a magnified look with your device.

Anterior segment pathology

Examples of clinical signs and pathology you may note on assessment of the anterior segment include:

- Foreign body: may be visible on the surface of the eye or embedded within the cornea or sclera with a rust ring if metallic. Associated clinical features include infiltrate, redness, pain, watering and a ‘foreign body sensation’. Remember to perform eyelid eversion: foreign bodies may be hidden under the top or bottom lids or stuck to the tarsal plate.

- Hyphaema: a layer of settled blood in the anterior chamber often due to blunt trauma.

- Hypopyon: a layer of settled ‘pus’ (white cells and debris) in the anterior chamber. Typically associated with severe corneal ulcers or endophthalmitis, but can also be seen in bad anterior uveitis.

- Corneal abrasion: redness, pain, watering and photophobia are common clinical features. Epithelial defects can be hard to see with the naked eye but will stain brightly and clearly when stained with fluorescein and viewed with a magnifier and blue light.

- Corneal ulcer: typical clinical features include blurred vision, pain, watering, photophobia and a staining epithelial defect with associated haziness (infiltrates) of the cornea. The infiltrate may appear fluffy and irregular. If severe, a hypopyon may also be present. Corneal ulcers are common in contact lens wearers.

- Limbal injection: dilated blood vessels at the junction of the cornea and sclera (limbus). This finding suggests intraocular inflammation. Most commonly seen in anterior uveitis and keratitis.

- Uveitis: limbal injection (typically unilateral), white deposits on the inside surface of the lower part of the cornea (keratic precipitates), misshapen pupil (posterior synechiae), watery eye with blurred vision and photophobic pain are common features.

- Acute angle-closure glaucoma (AACG): pain in and around the eye as well as generalised headache with nausea and vomiting. Reduced visual acuity with haloes around bright lights is characteristic. The cornea can become diffusely hazy with the pupil becoming mid-dilated and unreactive to light. Due to the high pressure, the affected eye will feel firm, compared to the unaffected eye, when felt through the lids.

- Subconjunctival haemorrhage: a painless type of red eye with a flat, bright red patch on the conjunctiva with sharply defined borders and normal conjunctiva surrounding it.

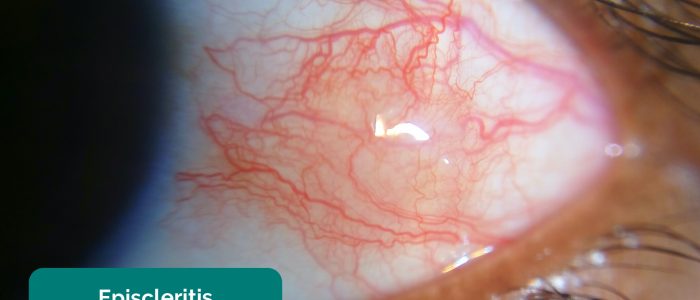

- Episcleritis: sectoral area of superficial conjunctival redness (unilateral) which is moveable with a swab (using topical anaesthesia) when pressed gently on the surface.

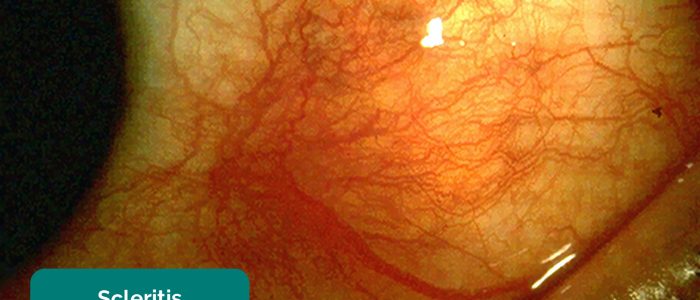

- Scleritis: deep red-purple localised conjunctival/scleral redness (unilateral). Will not move when touched with a cotton bud. Minimal watering, but very sore, especially to touch (may wake the patient from sleep). Can be associated with connective tissue diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis.

- Dry eye: reduced quality and volume of tear production. Most commonly age-related, but can also be secondary to conditions such as blepharitis (obstruction of meibomian glands) and connective tissue diseases. Clinical features include diffuse conjunctival injection. Using fluorescein, blue light and magnifier, punctate epithelial erosions on the cornea with a reduced or absent tear meniscus can be seen. When due to blepharitis, inflamed lid margins with crusting and matted eyelashes may be present.

To complete the examination…

Repeat the above assessments on the other eye if appropriate and compare your clinical findings.

Explain to the patient that the examination is now finished.

Thank the patient for their time and explain your findings and management plan.

Dispose of PPE appropriately and wash your hands.

Suggest further assessment and investigations

All of the following further assessments and investigations are dependent on the patient’s presenting complaint:

- If vision is blurred check visual acuity, pupils, fundal reflex and examine the fundi

- If there is discharge then consider treating with antibiotic or anti-virals depending on your clinical suspicion. Take a swab to help identify an infective organism if the patient’s symptoms fail to improve.

- If the patient has a history of eye trauma, consider imaging (e.g. X-ray or CT for a suspected penetrating foreign body or orbital fracture) and referring to ophthalmology and maxillofacial team for further management.

References

- Tripp on Flickr. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Pre-septal cellulitis. Licence: CC BY 2.0.

- Geeky Medics. Blepharitis.

- James Heilman, MD. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Allergic conjunctivitis. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Adapted by Geeky Medics. Bacterial conjunctivitis. Licence: Public domain.

- Jonathan Trobe, M.D. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Acute angle-closure glaucoma. Licence: CC BY.

- Jonathan Trobe, M.D. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Anterior uveitis. Licence: CC BY.

- Yoanmb. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Corneal ulcer. Licence: CC BY SA.

- James Heilman, MD. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Corneal abrasion. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Evan Herk. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Foreign body. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- EyeMD (Rakesh Ahuja, M.D.). Adapted by Geeky Medics. Hypopyon. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- FiP. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Subconjunctival haemorrhage. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Kribz. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Scleritis. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Imrankabirhossain. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Episcleritis. Licence: CC BY-SA.